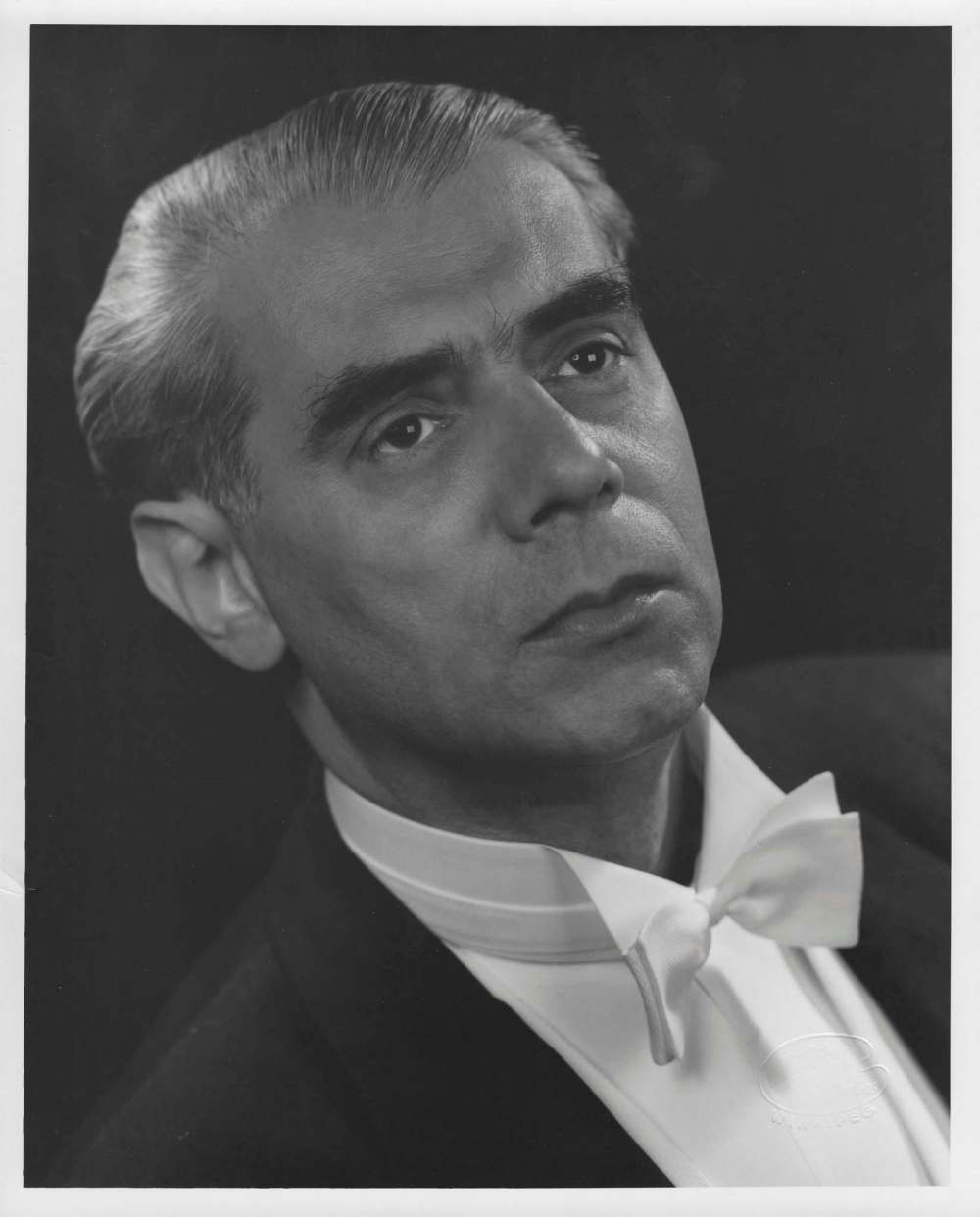

Remembering the maestro The WSO's first conductor, Walter Kaufmann, led a fascinating life, but his distinctive compositions were lost to time until a Grammy-nominated group unearthed them

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 24/08/2020 (1934 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

A new album by a Toronto chamber group is shedding light on the fascinating life and music of Walter Kaufmann, the first conductor of the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra.

Kaufmann was the WSO’s maestro for eight years, starting with its inaugural concert on Dec. 16, 1948, at the Civic Auditorium, where two of his compositions were performed.

“You’re always looking for a composer with a distinctive voice, and Kaufmann certainly has that,” says Simon Wynberg, the artistic director of the ARC Ensemble. ARC stands for Artists of the Royal Conservatory, and the group specializes in recovering suppressed music and has earned three Grammy nominations for previous recordings by composers whose lives were affected by the Holocaust.

Chamber Works by Walter Kaufmann, which will be released Friday, focuses on works he wrote as a Jewish refugee in India during the 1930s and ‘40s, prior to his arrival in Winnipeg.

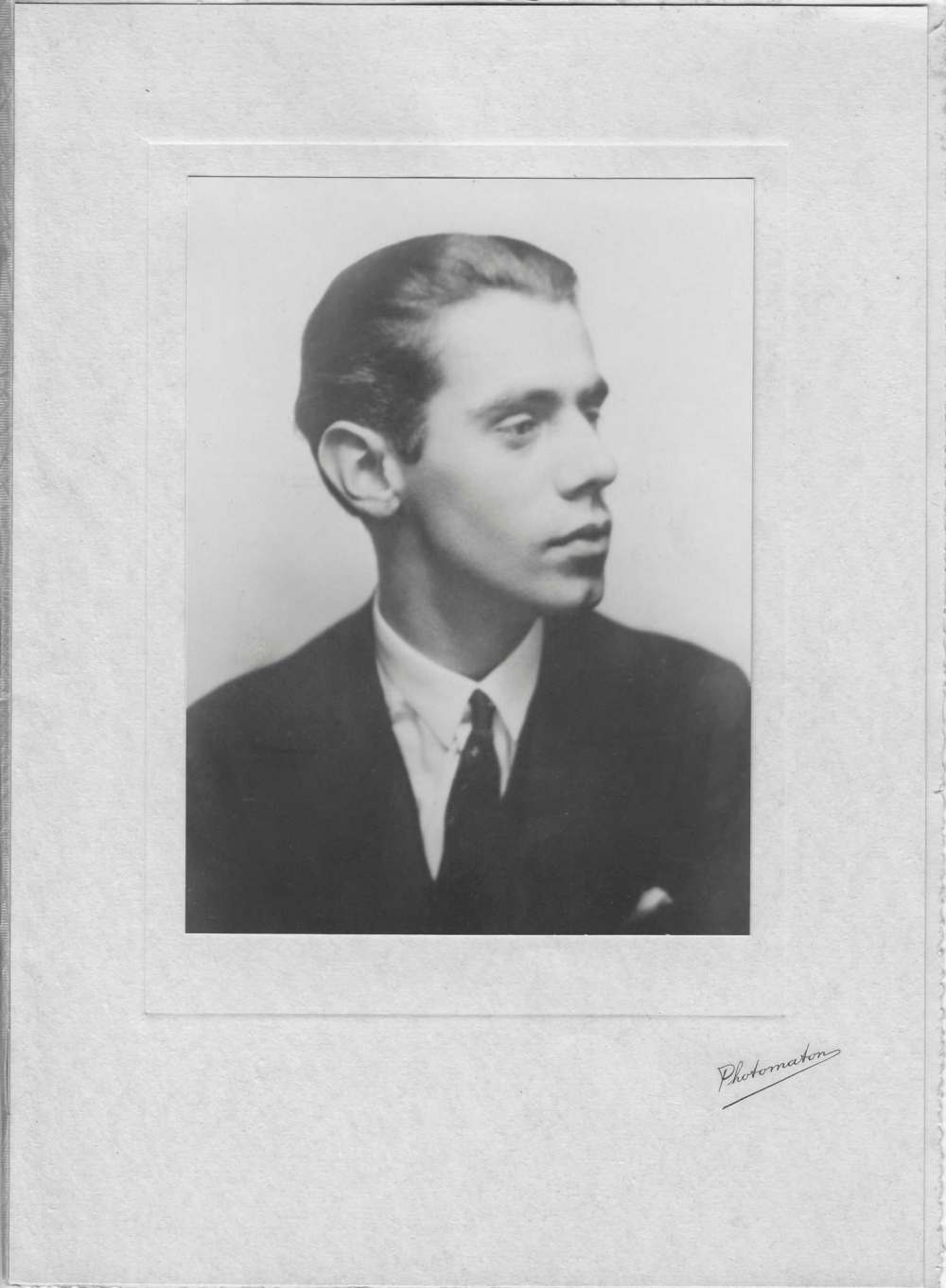

Kaufmann’s journey to Winnipeg begins when he was born in 1907 in what is now the spa town of Karlovy Vary, Czech Republic, which back then was known as Karlsbad, part of the Austro-Hungarian empire.

His family moved to Prague, where he first went to university, rented a flat from the mother of literary giant Franz Kafka, according to the CD’s liner notes, and met his first wife, Gerty Hermann, Kafka’s niece.

He would continue his musical studies in Berlin in the late 1920s and early ‘30s, where he focused on musicology and composing. It was then when the Nazis took over the government and began taking control of most aspects of German life.

Kaufmann decided instead of finishing his degree under a department run by a Nazi, it was time to leave the country altogether, despite the protests of his father, Julius.

“This was pretty early on (during the Nazi rule). That was back in 1933, when the threat was looming,” Wynberg says. “Kaufmann saw all sorts of signs that this was going to be a lot more serious than his father thought.”

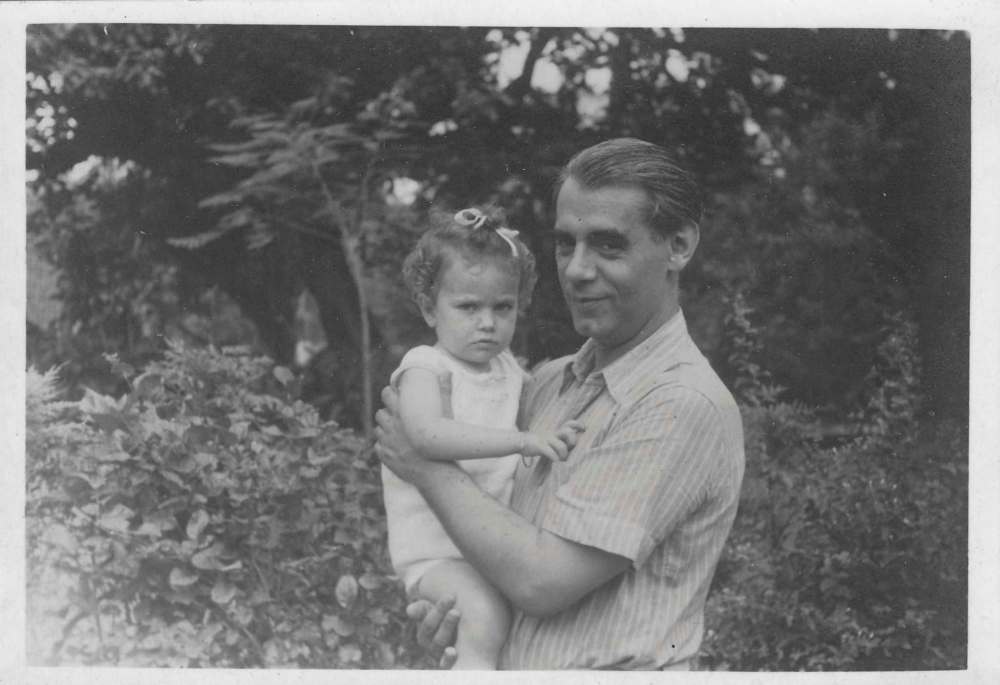

He was able to obtain a visa to sail to India, where he got a job with Air India Radio in Mumbai and set about composing. Meanwhile, much of his family, including his father, were murdered by the Nazis during the Holocaust.

“He definitely wanted to go to India because he was already interested in Indian music. There were some records of Indian music that were available in the 1920s that he had access to and he was absolutely fascinated by the sound of India,” Wynberg says.

The album’s liner notes delve into Kaufmann’s introduction to Indian music.

“When I heard the music on the gramophone for the first time, I found it alien and incomprehensible,” the composer is quoted as saying. “However, I knew that since this music was created by people with heart and intellect, one had to assume that many, in fact millions, had to appreciate or actually love it. I decided that the fault was entirely my own, and that the right way to understand it would be to undertake a study tour of the place of its origin.”

It was there he composed chamber and orchestral works, including the two string quartets, a sonata, a sonatina and a septet that make up Chamber Works of Walter Kaufmann.

“All of the pieces that were recorded on this album date from that time in India when he was experimenting with a hybridization of his traditional training,” Wynberg says, “and he was fusing that with all the knowledge he had picked up both before his arrival in India and while he was there.”

Both before and after their time in India, the Kaufmanns tried to move to the United States, and even enlisted a famous reference to get a job, but no luck.

He had become friends with Albert Einstein at university in Berlin, Wynberg says, but even a good word from one of humanity’s most famous scientists failed to open any doors stateside.

“Einstein had for years been trying to get him a job in the United States and he’d never managed to get that,” Wynberg says. “There was definitely a strong relationship there that lasted until Einstein’s death in 1955.”

So dreams of composing on Broadway were put on hold. After a stop in Halifax, Kaufmann finally got his break — conductor of the fledgling WSO.

“He jumped at it, and he had an experience with all sorts of orchestral playing. He had a long career and he had been well trained,” Wynberg says. “I think he saw this as an important stepping stone.

“He probably wasn’t expecting the change in weather going from (Mumbai) to Winnipeg, but he was certainly geared up for it.”

His marriage ended in Winnipeg, but it was here where he met Freda Trepel, a Winnipeg concert pianist who toured the world in the 1940s and ‘50s.

She was notable enough to perform at New York’s Town Hall during a North American tour and be reviewed by the New York Times, and Kaufmann wrote pieces specifically for her to perform. They married in 1951.

The WSO built up its subscription base with Kaufmann at the podium, but he left the organization and the city in 1956 after taking a job as a professor of musicology at Indiana University. He had a long career there, and continued composing music, Wynberg says.

He died in 1984, and while many of his works were performed throughout the years by a number of musical organizations, including the WSO and the Royal Winnipeg Ballet, the sheet music was left in his archives at Indiana University, along with decades’ worth of teaching materials and notes.

Wynberg and the ARC Ensemble were tipped off to the archive by Brett Werb, the musicologist of the U.S. Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C.

“Basically, no one had looked at it. Few people had investigated his biography,” Wynberg says. “Until the ARC Ensemble read through his works and put this recording together, there was no commercial recording of his music.”

Kaufmann himself might be the big reason his music has remained unplayed and unheard for so long. Self-promotion was not in his DNA, Wynberg says.

“He would write a piece, it would be performed and he would move on,” Wynberg says. “He would be the last person ever to be on social media. It would have not attracted him at all.”

alan.small@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter:@AlanDSmall

Alan Small has been a journalist at the Free Press for more than 22 years in a variety of roles, the latest being a reporter in the Arts and Life section.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.