Connection between cultures Indigenous exhibitions explore discussions about environment, western globalization policies and seal hunt

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 29/11/2019 (2206 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The sun was only just starting to rise in Tuktoyaktuk, N.W.T., when Inuvialuk artist Maureen Gruben answered the phone to discuss her new work Breathing Hole, which is about to debut in Subsist, one of two exhibitions opening Saturday at the Winnipeg Art Gallery.

Art preview

Subsist and ᐃ

Winnipeg Art Gallery

● To May 2020

● Hours: Tuesday to Sunday 11 a.m. to 5 p.m., Fridays 11 a.m. to 9 p.m.

● Admission: $12 adults, $10 students and seniors, children under 5 free

● For more details, visit wag.ca

Subsist features photography, drawings, sculpture and installations that aim to spark conversations about the environment, western globalization policies and the seal hunt, a subject that hits close to home for Gruben.

She was born and raised in Tuk, a small Inuvialuit community on the shores of the Arctic Ocean, where seal hunting is a way of life.

“It’s just beautiful here,” Gruben says. “I don’t want to be anyplace else.”

Despite its location north of the Arctic Circle — it holds the honour of being the only Canadian settlement on the coast of the Arctic Ocean with road access — it was only a mere -15 Cin Tuk, she said during the phone interview.

“It’s mild,” she says. “Winnipeg gets colder than it does here sometimes!”

Still, with an average January low of -30 C, it’s just as important in Tuk to have good winter clothing as it is here. Gruben grew up learning how to make these items, which led to an interest in fine arts.

“It wasn’t called art,” she says. “It was just a lifestyle. But that’s how I started creating and it just progressed from there.”

Gruben spent a decade in Victoria, B.C., where she raised a family and attended the University of Victoria, ultimately earning her bachelor of fine arts. Now that her children are all grown up, she has returned home to Tuk and turned her focus to arts, full time.

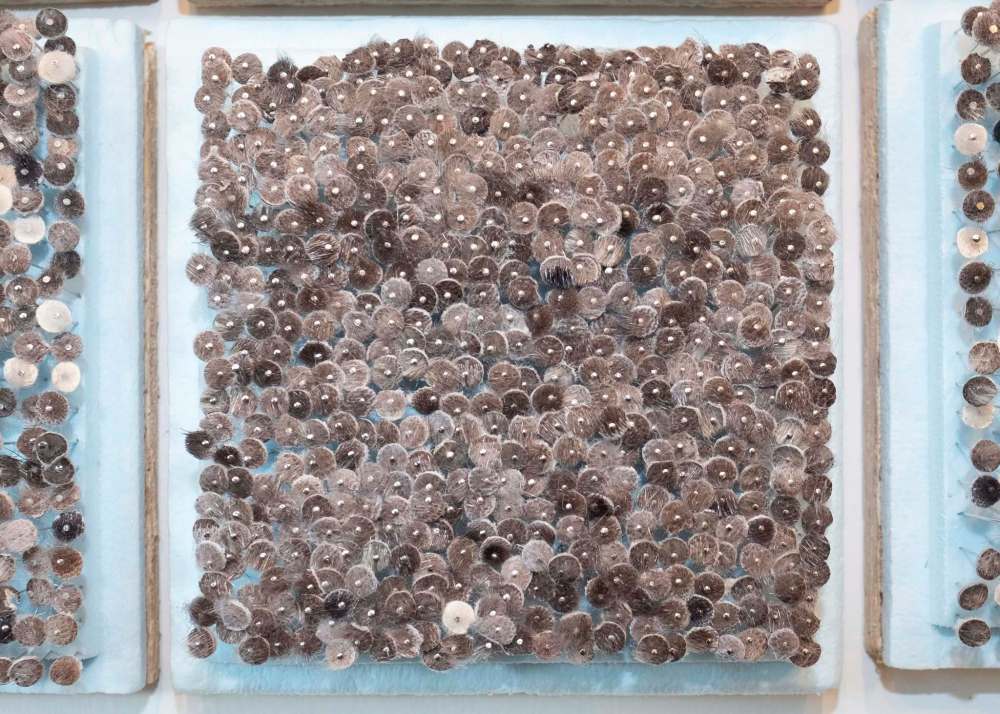

“First, I did Seal in our Blood, which is currently on display in the National Gallery of Canada, and all the sealskin scraps used in Breathing Hole came from that.”

“I didn’t want to throw the scraps out,” she says. “We don’t waste material. It’s too precious to throw out. I was trying to think of a way to utilize the scraps and thought of when you punch holes in paper and make confetti. I thought I’d try that with the sealskin.”

Gruben’s first attempt failed: the hole-punch she bought at Staples broke. Undeterred, she went on a hunt for a sturdier hole-punch. Another problem arose: what to do with the all the sealskin confetti?

“As an Inuit woman, we are taught how to make our own clothes, so I thought about dressmakers pins,” she says. “My husband is a contractor and I found Dricore (moisture barrier). I thought to punch the sealskin pins on to the Dricore. It has a beautiful blue colour, which is reminiscent of ice.”

A breathing hole, for the unfamiliar, is the hole in the ice where a seal comes up to breathe.

In the middle of the Breathing Hole project, Gruben got a breath of fresh air herself when she was invited to the Yukon School of Art to work with students, where she enlisted their help on the project.

“They were sitting in a circle around a table, working with their hands and then they started telling stories,” she recalls. “They were finding out things about each other that they never knew before. They loved it. They absolutely loved it.”

Some 18,000 pins later, Gruben is finished with the project, but notes it’s a piece that can continue to grow and be added on to if others wish to continue with it.

She warns that it takes a lot of patience.

“Just like a hunter at the seal hole,” Gruben says. “I thought of my ancestors a lot during the project because of their endurance, patience and perseverance.”

Breathing Hole is just one of the works by Inuit and Indigenous artists on display in Subsist, but all of the pieces of art have one thing in common: they all draw from traditional knowledge to present a new contemporary perspective — a commonality that is also shared in the exhibit ∆, which sits just outside the WAG’s Muriel Richardson Auditorium and also opens Saturday.

“We’re excited to change up that space and have a dialogue,” says Jaimie Isaac, curator of Indigenous and contemporary art at the WAG. “It’s the official year of Indigenous languages and we are excited to acknowledge that.”

Joi Arcand’s neon Cree syllabic installation, which was part of the WAG’s 2018 groundbreaking exhibition Insurgence/Resurgence, kicks off Subsist.

It features a selection of ceramic and soapstone sculptures crafted through an artistic exchange between the Ministic Sculpture Co-operative, a group of Anishininiwak carvers from Garden Hill, who travelled to Rankin Inlet, Nunavut, in 1968 to research Inuit stone carvings.

“Inuktitut and Anishininiwak are different, but esthetically similar, but we found one common syllabic: ∆. It embodies the idea of self-determination that was brought forth in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.” – Jaimie Isaac, curator of Indigenous and contemporary art at the WAG

“It was interesting to find so many connections between the Inuit and the Anishininiwak,” says Jocelyn Piirainen, WAG’s assistant curator of Inuit art. “The inspiration shows in the artwork, the connection between both cultures.”

“Inuktitut and Anishininiwak are different, but esthetically similar,” Isaac adds, “but we found one common syllabic: ∆. It embodies the idea of self-determination that was brought forth in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.”

Both Subsist and ∆ seek to enter into a larger dialogue with works from other WAG collections, and it leads up to the grand opening of the gallery’s Inuit Art Centre in 2020, which will also feature Gruben’s artwork.

“Art is great way to tell a story,” Gruben says at the end of our phone call. “It’s a great way to gather and start talking to one another.”

“It’s a great way to tell your own story.”

frances.koncan@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @franceskoncan

Frances Koncan (she/her) is a writer, theatre director, and failed musician of mixed Anishinaabe and Slovene descent. Originally from Couchiching First Nation, she is now based in Treaty 1 Territory right here in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.