Connected by workplace, friendship and now kidney transplant Alan Small had braced for spending years waiting for a kidney transplant. Then friend and colleague Jill Wilson became a live donor.

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 18/10/2019 (2241 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Have kidney, will travel

Free Press writer makes momentous decision to join chain gang, donates vital organ so friend and colleague in deteriorating health gets one he desperately needs

‘You’re going to feel like you’ve been hit by a truck.”

Nobody sugarcoats the way a nephrectomy is supposed to affect you. When you decide to become a live kidney donor, the phrase “hit by a truck” is bandied about with some regularity before the surgery takes place.

I’ve never been hit by a truck, so I don’t have a reference point, but I will tell you that I have had worse hangovers.

Everyone’s different, of course — I am fit, healthy and relatively young — and I wouldn’t dream of minimizing or generalizing the potential effects of a major surgery, but I was sitting on a patio, drinking a beer to celebrate my 48th birthday, six days after donating a kidney.

This is not to say I didn’t feel the effects of the 5 1/2-hour laparoscopic operation. There was some pain around my incisions, entirely manageable with Dilaudid in the hospital and a few Tylenol 3 afterward. I napped for several hours a day in the weeks following, and sitting upright was not my favourite thing, nor was wearing anything with a waistband. (Honestly, you could say this of me pretty much any time.) Even now, months after surgery, I have some numbness and sensitivity in my left thigh and stomach.

But in general, any minimal suffering was entirely outweighed by the warm glow of doing a good deed — that and knowing I’d be able to guilt people into fetching things for me for months to come.

When the nephrologist came to visit me in the hospital (where I was for just two days), he poked his head around the curtain and made a surprised face. “Oh!” he said. “You look great! Most people look like they’ve been hit by a truck.”

● ● ●

If you decide to donate a kidney — especially to someone who is not a family member and to whom you have no real obligation — you have to be prepared to explain your reasons, both to friends and family, and to the medical professionals entrusted with your care.

The psychiatrist you visit as part of the pre-approval workup will ask you why. The medical questionnaire you fill out will ask you why.

The answer, however, is complicated and multifaceted.

Of course, the obvious reason is that Alan Small, my friend and co-worker, was suffering from kidney failure. His family members were not eligible to donate. He was on home dialysis and had little hope of a quick match with a deceased donor, meaning he could be on the waiting list for more than a decade; watching him work through illness was disheartening and sad. There was simple solution, and I was in a position to provide it.

I wish I could say it was an act of pure altruism, but most of the time, it felt like something I needed to do to cosmically return the favour of the lifetime of good luck I’ve had (my mother will tell you she doesn’t know how I sit down with that horseshoe up my butt).

I’m healthy and always have been; the only medication I take is a B12 supplement. I don’t have children. I’m not squeamish or afraid of surgery or hospitals. (I have a pretty low pain threshold and I’m a bit of a whiner, but neither of those seems like a good excuse to opt out.)

I filled out my (now obsolete) organ donation card as soon as I got a driver’s licence. I registered to be a donor at www.signupforlife.ca the moment I heard about it.

Reading Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers, Mary Roach’s humane, hilarious book about what happens to us after we die, only solidified my belief that if my body could be of some use after death, have at it. Crash test dummy? Be my guest. Medical-school research tool? Go right ahead. Take my skin, my bone, my corneas — strip me for parts and dispose of the scrap in whatever way is cheapest and most environmentally friendly.

Alan Small, my friend and co-worker, was suffering from kidney failure. His family members were not eligible to donate. He was on home dialysis and had little hope of a quick match with a deceased donor.

My blood type is O-negative, which means I’m a universal donor — my blood can be used by patients of any type. And I have actually been the beneficiary of donated tissue. When I required a dental implant some years ago, my thinning upper jaw was augmented with human bone.

I’m a cultural Jew, not a religious one, but I like the idea of doing a mitzvah. (As an essentially lazy, selfish person, I also like the idea that donating an organ potentially means never having to do anything nice for anyone again.)

Why do we need kidneys?

• They filter waste from the blood.

• They control water and mineral balance.

• They secrete vitamins and hormones that control blood pressure, make red blood cells and maintain healthy bones.

But honestly, it was a television crush that tipped the scales. In spring of 2017, I found myself watching the short-lived NBC hospital drama Heartbeat. The only thing that kept me coming back to the overheated melodrama was the dreamy actor Don Hany, who first became my TV boyfriend during his two seasons on the Australian dramedy Offspring (it’s on Netflix and you should watch it because it is totally charming).

On one episode, guest star Jobeth Williams played a live kidney donor. I had already been toying with the idea of looking into donation and since then, it had seemed to come up a lot, the way these things do. I made a mental deal with myself: If Jobeth lives at the end of the episode, I will take the first steps toward becoming a donor.

Williams’ character came out of surgery successfully, but as she crossed the hospital lobby to go home, she collapsed on the floor, unconscious.

And I felt, not relieved, but… disappointed.

It turned out the character’s collapse had nothing to do with the surgery, and she recovered.

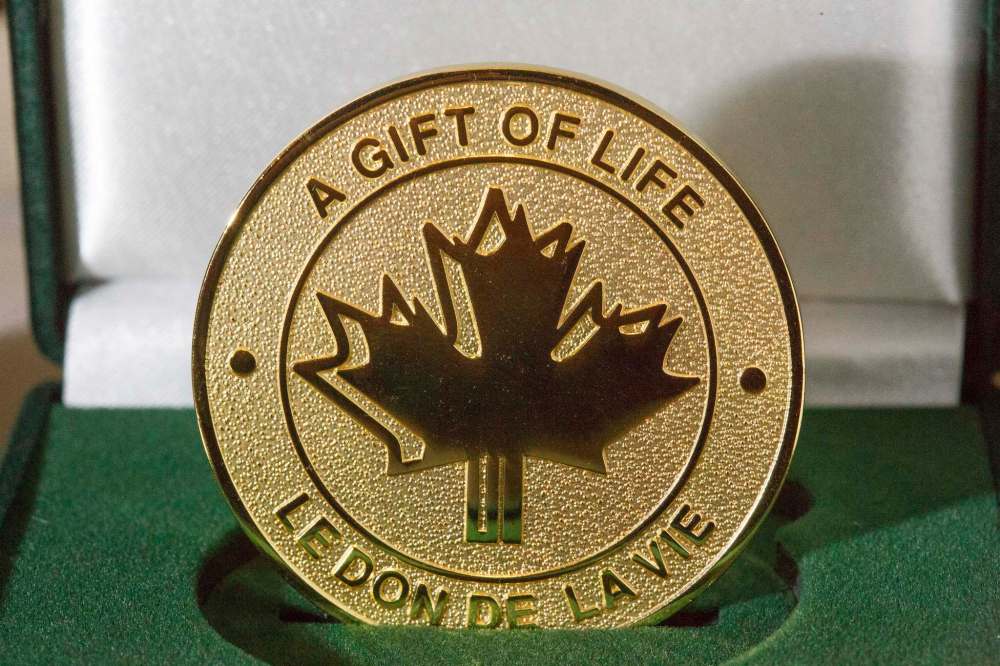

The next day, I emailed Transplant Manitoba’s Gift of Life program at the Health Sciences Centre to inquire about becoming a kidney donor.

• • •

A couple of weeks after contacting the Gift of Life program, I get a package in the mail with a list of appointments to test my suitability as a donor.

At the first of these appointments, I and two other potential donors meet our transplant co-ordinator, Camille Boucher. A tiny woman with huge eyes and a small voice, and a lot of jangling bracelets, she explains that she is our advocate. She stresses that there is no obligation; we can drop out of the process at any time, right up to the moment we’re wheeled into the operating room.

We watch a short film explaining the risks of donation and then head across the street to Canadian Blood Services to do a blood test that will assess our compatibility. I already know my blood type is compatible, but there are lots of other factors at play, including cross-matching that looks for antibodies in the recipient against the donor, and HLA typing to test the DNA that makes up my immune system (this tells you how close a match you are, on a range from zero to six out of six).

About three weeks after my initial meeting, Boucher calls me at work.

“I’m afraid you’re not a match,” she says. “If we were to put your kidney in his body, his body would begin to attack it immediately.”

Kidney Paired Donation Program

Prior to the formation of the Kidney Paired Donation Program in 2009, transplant candidates with an incompatible living donor would have been added to the ever-growing deceased-donor wait list, or would have had to proceed with a transplant that was far from optimal because of potential rejection.

Prior to the formation of the Kidney Paired Donation Program in 2009, transplant candidates with an incompatible living donor would have been added to the ever-growing deceased-donor wait list, or would have had to proceed with a transplant that was far from optimal because of potential rejection.

Now, three times a year, potential donors who are incompatible with their intended recipient — or non-directed anonymous donors who are willing to donate to any suitable recipient — are entered into the Canadian Transplant Registry, an electronic database operated by Canadian Blood Services, in order to find matches.

There are three types of exchange formats:

• The first, paired exchange, is the simplest. It involves the matching of two incompatible pairs: donor A gives to candidate B, while donor B gives to candidate A.

• The second format is called the n-way exchange and involves more than two pairs (up to six pairs) where the donor of the last pair must match the candidate of the first pair, forming a closed loop. This means a donor is assured that her intended recipient gets a kidney, just not directly from her.

• The domino chain is the most common format and has resulted in the largest number of transplants. It begins with an anonymous donor (the non-directed anonymous donor, or NDAD) who has contacted his or her local Living Donation program and offered a kidney to anyone in need. When this kidney goes to the candidate of an incompatible pair, a chain of up to six transplants can result, with the donor of the last pair donating to a patient on the NDAD’s local wait list.

As of Aug. 1, these anonymous donors — whose generosity is not conditional on a friend or family member receiving a transplant in return — have been responsible for kicking off 415 of 694 completed kidney-paired donation transplants; 60 per cent of these transplants since the program’s inception have been via domino chains.

The time of the chain’s completion is 111 days from the time patients are informed of a match. In that time frame, there is the possibility chains will collapse. If once person withdraws from a chain, the donations cannot go forward.

If the donor has to travel to donate (quite likely), the cost — transportation, hotel and meals — for the donor and a companion are covered by the Living Organ Donor Reimbursement Program, which is run by Manitoba Health, Seniors and Active Living and provides coverage for out-of-pocket expenses to donors who provide a kidney or partial liver to a patient living in Manitoba. The maximum reimbursement is $5,500, which includes up to $3,000 for travel and accommodation, $750 for meals, up to $250 for parking and up to $500 for home support (to assist donors with household and property-related expenses). Depsite this attempt to remove financial barriers, however, KPD may not be an option for those who cannot afford to pay the related expenses up front.

So. Once again, not really relieved, but disappointed and saddened. However, Boucher points out it’s not the end of the road. There is always the option of kidney paired matching or KPD.

This Canada-wide program run by Canadian Blood Services has been a game-changer since its inception in 2009. Living-donation and kidney-transplant programs across the country register potential donors and transplant candidates into the Canadian Transplant Registry (CTR). Then, three times a year, sophisticated matching algorithms identify potentially suitable matches of transplant candidates with potential donors.

The matches are grouped into “chains” of donor exchanges so that each transplant candidate in the chain receives a suitably matched kidney transplant.

Donors have to be willing to give up an organ to a stranger, likely in another province. In exchange, another stranger who’s a better match will give their intended recipient a kidney.

Boucher asks me if I would be amenable to following through with the battery of tests to assess my suitability for the program, and I consent.

Some of them are mildly unpleasant. I’m lucky enough to be able to work from home occasionally, so I can do that on the two separate days when I have to complete a 24-hour urine test. It’s not that I couldn’t lug around a bright orange three-litre plastic jug of my pee all day, but it seems like both an embarrassment and a health hazard.

The glucose tolerance test (since removed from the list of necessary labwork) checks for diabetes and involves doing a fasting blood test, chugging what feels like a huge quantity of sickly sweet, orange-flavoured glucose solution, sitting quietly for two hours, and then having another blood test. It’s a nice opportunity to catch up on your reading, but there are probably nicer places to do that than the lab waiting room at HSC, which is filled with some deeply unwell people.

Any live organ donation will require many weeks off work. Manitoba offers 13 weeks of EI benefits specifically for organ donors, but many private or workplace insurance plans cover time off through short-term disability or sick time.

The others — blood tests, X-ray, EKG, CT scan, Mantoux test for tuberculosis — are routine and scheduled to be handled swiftly and efficiently at HSC, thanks to May Villarba, the program’s unit clerk. Women are also required to have had a Pap test within the last two years.

Boucher goes through my results with me. One of the warnings you receive at the beginning of the process is that you may find out alarming things about your health that would otherwise have remained unknown.

The only red flags are my blood pressure — readings at the clinic have been high-normal — and a note on my EKG regarding bradycardia. The latter is not a concern; a low resting heart rate is expected in people who exercise a lot. But Transplant Manitoba nephrologist Dr. Martin Karpinski has requested that I wear a 24-hour blood-pressure monitor to further investigate my BP, which isn’t high enough to exclude me as a donor, but is something to ponder.

The kidneys control blood pressure, there is a slight chance of high BP requiring medication post-donation; that risk obviously goes up if your pressure is high to begin with.

I meet with a psychiatrist to make sure I’m mentally prepared for the potentially stressful or disappointing process (there is no guarantee a transplant won’t be rejected), while social worker Kristin L’Heureux discusses the supports — financial, emotional and physical — necessary for donation, especially one taking place out-of-province.

Donor statistics

• Mortality rate: One in 3,000 or 0.03 per cent.

• Surgical complications: chance of bleeding, blood clot in legs or lungs, infection, drug allergy or side-effect, lung collapse, post-op pneumonia or urinary tract infection, wound infection. Slight risk of injury to teeth or throat from breathing tube.

• Mortality rate: One in 3,000 or 0.03 per cent.

• Surgical complications: chance of bleeding, blood clot in legs or lungs, infection, drug allergy or side-effect, lung collapse, post-op pneumonia or urinary tract infection, wound infection. Slight risk of injury to teeth or throat from breathing tube.

• Slightly elevated risk of kidney failure post-surgery.

• Life expectancy is unchanged. Some studies have shown that kidney donors actually live about two years longer than the general population, but that’s not because living with a single kidney confers longevity; it’s because donors are usually healthier than the general population.

• The remaining kidney will increase its function; most donors have function of about 80 per cent of what it was pre-donation.

• No medication required.

• People have a 90 per cent lifetime risk of high blood pressure; this may occur earlier in living donors.

• Risk of severe hypertension during pregnancy is higher in women who have donated a kidney (six per cent vs. three per cent).

Any live organ donation will require many weeks off work. Manitoba offers 13 weeks of EI benefits specifically for organ donors, but many private or workplace insurance plans cover time off through short-term disability or sick time. Manitoba Health covers out-of-pocket expenses for travel, accommodations and food.

My final appointment is with surgeon Dr. Rahul Bansal, a matter-of-fact urologist at the St. Boniface Clinic with a reassuring demeanour who takes me through the potential operation, which he says is likely to be laparoscopic (three small incisions and a slightly larger one above the pelvic bone, rather than an open surgery with long surgical incision, which means a more difficult recovery).

“That’s a beautiful kidney,” he says, indicating a shadowy presence on my CT scan. “Oh, get out of here,” I say jokingly, making a “you flatter me” gesture. He does not find me amusing, or maybe he’s heard it a million times before. He also doesn’t care for my joke about ruining my bikini-modelling career as he shows me where the four small incisions will be made (I’d assumed they’d take my kidney from the back, where it resides, but apparently removing things from the human body is not as straightforward as the game Operation).

Dr. Bansal clears me for surgery, the last hurdle before I can be entered into the KPD program. I make it in just under the wire for the next Canada-wide matching cycle, but Dr. Karpinski has already told me not to get my hopes up. With a difficult-to-match transplant candidate, I should expect to be in the system for three or four years before a chain can be made.

I go into the program on a Friday. The following Wednesday, Boucher calls me on my cellphone. “We have a chain!” she says excitedly.

• • •

It is somewhat disconcerting to be told, the day before major surgery, that you have a heart murmur.

“It’s nothing, really, just a faint murmur,” the anesthetist tells me, holding a stethoscope to my chest and listening intently. “Nothing to worry about.”

The news does not fill me with confidence, however, especially as my surgeon has also informed me that, because I have two arteries connected to my left kidney (most people have one), my operation could be more complicated and lengthy; there’s a possibility it won’t be able to be done laparoscopically. I’m not concerned about the scarring, but open surgery does have a longer recovery time, with more potential for pain.

Why donate?

• More than 4,000 people in Canada are awaiting organ transplant; every 36 hours, one of those people dies. In Manitoba, 200 people are waiting for a kidney.

• Manitoba has one of the lowest organ-donation rates in Canada, which itself ranks extremely low among developed countries. In 2018, 58 kidney transplants took place in Manitoba; 26 of those were via living donors.

• More than 4,000 people in Canada are awaiting organ transplant; every 36 hours, one of those people dies. In Manitoba, 200 people are waiting for a kidney.

• Manitoba has one of the lowest organ-donation rates in Canada, which itself ranks extremely low among developed countries. In 2018, 58 kidney transplants took place in Manitoba; 26 of those were via living donors.

• A person is five times more likely to require an organ transplant than to qualify to be a donor.

• Religion is often cited as a reason people might not wish to donate their organs, but many of the world’s major religious groups actively encourage it; those that don’t leave the choice up to the individual. The main groups where donation is not encouraged or is unlikely are Shinto, Jehovah’s Witness and Christian Science.

• A living donor can give a kidney, part of the liver and pancreases.

• Many transplants from a living donor may last more than 20 years; kidneys from a deceased donor don’t last as long.

• If more people came forward to donate, it might be possible to move away from the dialysis-first model currently in play, in which potential recipients are not placed on an active waiting list until they’re already on dialysis. A live donation is a far more effective treatment for kidney disease than long-term dialysis, resulting in better health, a longer life and a better quality of life.

It took a while to get to this point. Though I’m not allowed to know how many pairs are involved in this KPD chain, I know it’s a lot. That means a lot of co-ordination between different transplant teams in cities across Canada, many of which have different standards of suitability for donation.

Three days before my scheduled operation, my mother and I flew to this city in another province so I could undergo final testing before going under the knife (the location can’t be revealed owing to health privacy rules; I’m not to know who received my kidney and they’re not to know who donated it). Alan will get his kidney in Winnipeg the day after I donate.

Afterward, I will recuperate for a week — two days in hospital and five days at a hotel — before I can fly home, because sitting on a plane for hours raises the risk of blood clots. (I am vigilant about doing my exercises to prevent clots, which include walking around as much as possible; on the fifth day after the operation, I walk almost 5,000 steps.)

Beforehand, though, my mum and I pack in some touristy activities between more blood tests and medical questionnaires. We discover an amazing brew pub and have a fantastic fancy dinner, where the management gives us free drinks. (Note: my mum played the kidney-donation card, not me.)

The hospital egg-salad sandwich that was truly one of the worst things I have ever put in my mouth– and I have eaten hkaire, the rotted shark served in Iceland.

Finally, it’s time. I’m at the hospital hours before my 9 a.m. surgery, my mother beside me as we wait.

Luckily (because I am lucky), the anesthetist is able to put me under before inserting the biggest of the three IVs into my wrist — the tube is the diameter of a McDonald’s drinking straw and I have been dreading it; the bruise it leaves on removal lasts more than three weeks.

It feels like no time has passed before I wake up, groggy and thirsty. I have no idea that the surgery went longer than expected, and that my poor mum was anxiously waiting to pass on news to my boyfriend and sister at home.

When I finally get up the nerve to lift up my gown after being wheeled out of the OR, my abdomen is a battleground of bruises. There are five scars, not the expected four — four very small and one longer 10-centimentre one above my pubic bone, all held together with thick rows of Frankenstein-style staples. My abdominal cavity has been pumped full of air to make room for the surgeon to manoeuvre and it looks like it wants to pop.

But I feel so much better than I anticipated that I’m almost guilty about it. However, just so you don’t think it was all sponge baths and Jell-O, here are five crappy things about my kidney-donation experience:

• The short-lived and intermittent but excruciating pain in my shoulders that is a common side effect of the air injection. It was immune to painkillers, but it dissipated after a couple of days.

• The angry reaction I developed to the adhesive holding the gauze over my wounds. When it was removed, the skin underneath was blistered and painful — more painful than the incisions.

• The numbness in my left thigh and upper abdomen and the unpleasant tingling as the feeling slowly returns. This is owing to the jackknifed position you’re in during surgery.

• The monumentally jerky urology resident who talked to me and the wonderful nurses like we were idiots.

• The hospital egg-salad sandwich that was truly one of the worst things I have ever put in my mouth — and I have eaten hkaire, the rotted shark served in Iceland.

Flying home isn’t a picnic, as I’m not allowed to lift anything heavier than 10 pounds for two weeks and I am trying to disguise the fact that I’m wearing a nightgown by jazzing it up with a scarf (I did not succeed). However, I do recommend having someone push you through the airport in a wheelchair; everyone is much nicer to you than normal. Want some extra perks? Mention you just donated a kidney.

• • •

Six days after the operation, I return to the surgeon’s office so he can assess my incisions and look at my blood-test results, to be sure my single kidney is functioning well.

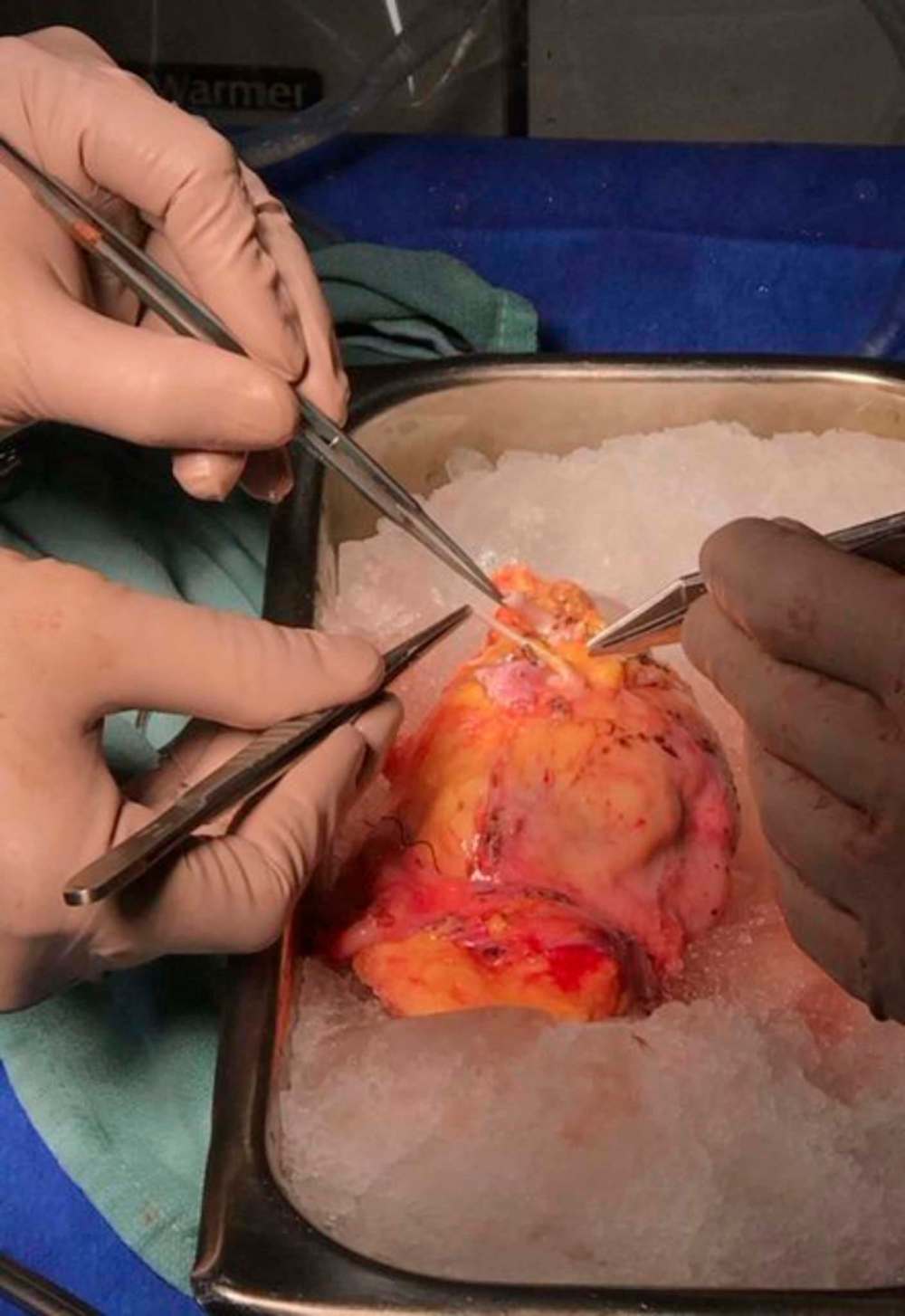

The doctor (I wish I could use his name, because he was so gentle and caring and deserves to be publicly recognized) happily shows me a picture he snapped on his phone — my kidney sitting in a bowl of ice.

“It was a beautiful kidney,” he tells me, which is a weird compliment you don’t expect to hear twice in your life.

It looks nothing like I’d expected (I was picturing a giant red kidney bean), but more like a chicken breast.

After removing it via the long pelvic incision, he transplanted my kidney into a waiting patient, where it began to make urine the second it was connected. “You never get tired of seeing that,” he says.

It makes me well up a tiny bit to hear it.

• • •

I am a weeper. I cry at movies. I cry at plays. I cry at TV commercials. But I only cry four times during this process, which is how I know it was no big deal.

The first time is when I’m about to be wheeled into surgery and the transplant co-ordinator — Camille Boucher’s counterpart at the hospital I’m in — stops by my bed. Her kindness and gratitude (of which I don’t feel entirely worthy), combined with a bit of fear, open up some kind of valve in me and I sob for a minute.

The second time is when I accidentally lean over the back of a chair and it stabs me in my pelvic incision. It’s not even the pain, so much, as the shock of being reminded that the body is a fragile container that is not meant to have extra holes in it.

The third time is while reading E. Jean Carroll’s Vanity Fair account of being raped by Donald Trump — just par-for-the-course rage tears, perhaps heightened by emotional fragility.

The last time is with my mum in our hotel room. She has spent the week taking care of me, sitting the OR waiting room for hours, walking with me as I shuffle slowly around the hospital corridors, shlepping to a nearby grocery store to buy me pretzels and hummus, letting me pick what Netflix movies to watch — basically enjoying the world’s worst vacation — and I’m suddenly overwhelmed by how fortunate I am to have her.

But I don’t cry when I finally hear that Alan’s surgery has gone swimmingly. I’m just joyful.

It almost doesn’t seem fair that I get to feel this good for doing something so easy. Lucky me.

jill.wilson@freepress.mb.ca Twitter: @dedaumier

•••

Sweet organ music

What’s a kidney between friends? For Free Press arts editor Alan Small, its an incredible gift that has given him a new lease on life and left him at a loss for words

Having kidney disease is a bit like the old cliché that you can never quit the Mafia or the CIA: once you’re in, you’re in for life. There’s no turning back.

Like many hit with the diagnosis, I found out about it the hard way in January 2006 — from a doctor in a hospital room. Dr. Justin Walters, a nephrologist at St. Boniface Hospital, wrapped the news of my damaged kidneys in a silver lining; I was, he said, an ideal candidate for a transplant.

It was shocking and difficult to digest. I was only 38. Suddenly I had an explanation for the headaches and distorted vision I’d been experiencing. A visit to my optometrist turned into an urgent same-day examination by an ophthalmologist. There I was informed that my blood pressure was dangerously high and I was instructed to head directly to St. B for a CT scan and then to check in at the emergency department. In that order. Do not pass go…

I was admitted and spent time in the intensive-care unit where, over several days, my blood pressure was reined in and returned to something approaching normal.

And I got a crash course in the first of four main treatments for patients with diseased kidneys: changes — big ones — in my diet. Shopping for groceries became significantly more complicated as I now had to pay attention to the nutrition labels.

Discovering the truth about sodium levels in the foods I liked was both sad and sobering. Later on, I’d have to watch my phosphates as well — who watches their phosphates? — and that meant saying goodbye to dairy, nuts and colas, among other favourites.

Fruits and vegetables and the meat counter were safe havens, but the canned-food aisle was a bit of a minefield, I discovered; some healthy choices, many not. And the frozen-food section was off-limits, high sodium content ready to attack with every freezer door opened.

•••

The second treatment involves medication, but it’s limited to chemicals that control blood pressure, preventing further kidney damage. There are few pharmaceutical options that will reverse the deterioration of the tiny filters inside the kidneys or boost the compromised organs’ efficiency, and they hadn’t worked in my case.

•••

Treatment No. 3 is dialysis, something I dreaded as soon as I learned of my diagnosis. To me, it sounded like the end of the road and loomed larger each time I had an appointment at the renal clinic at St. Boniface Hospital.

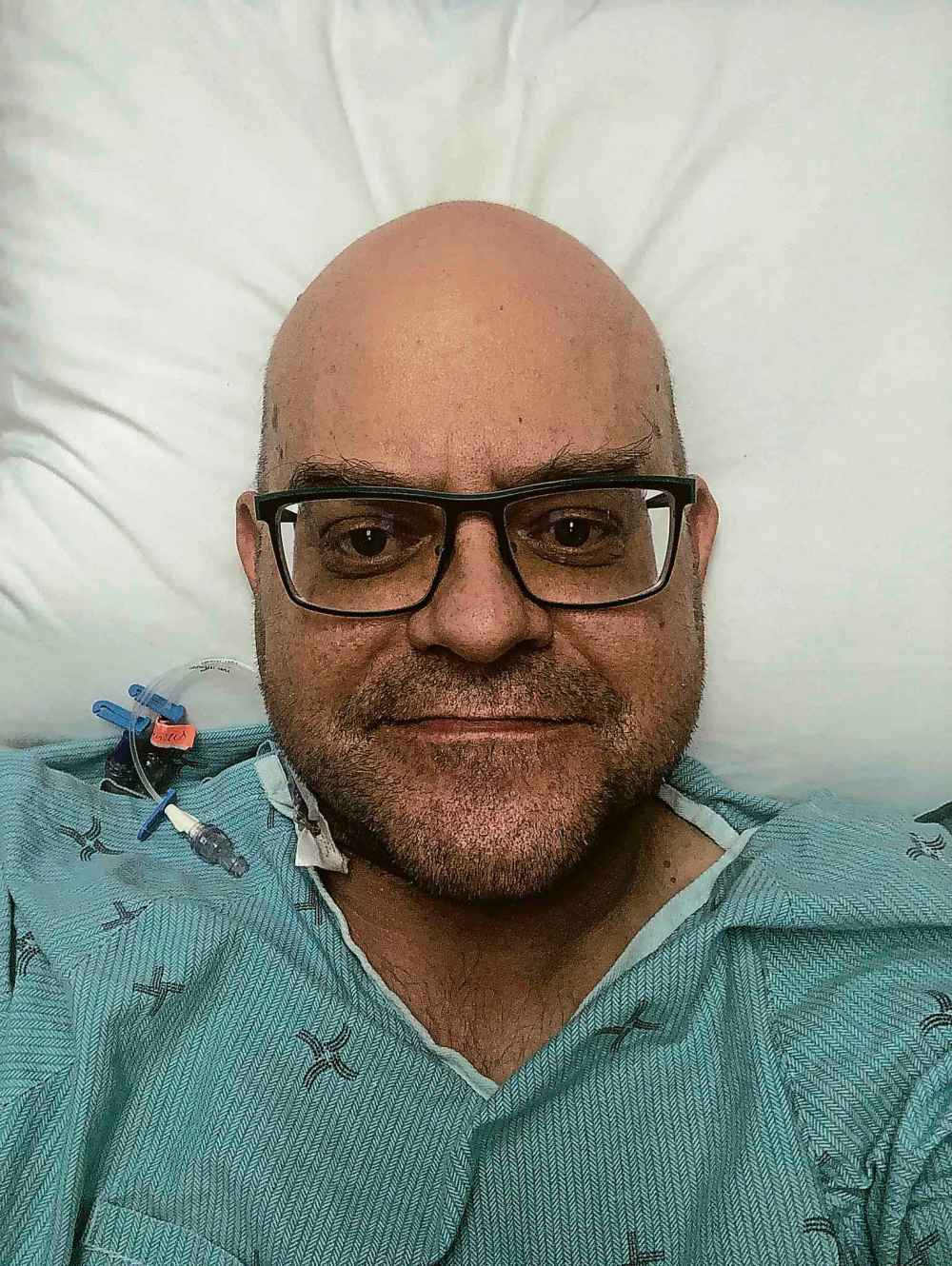

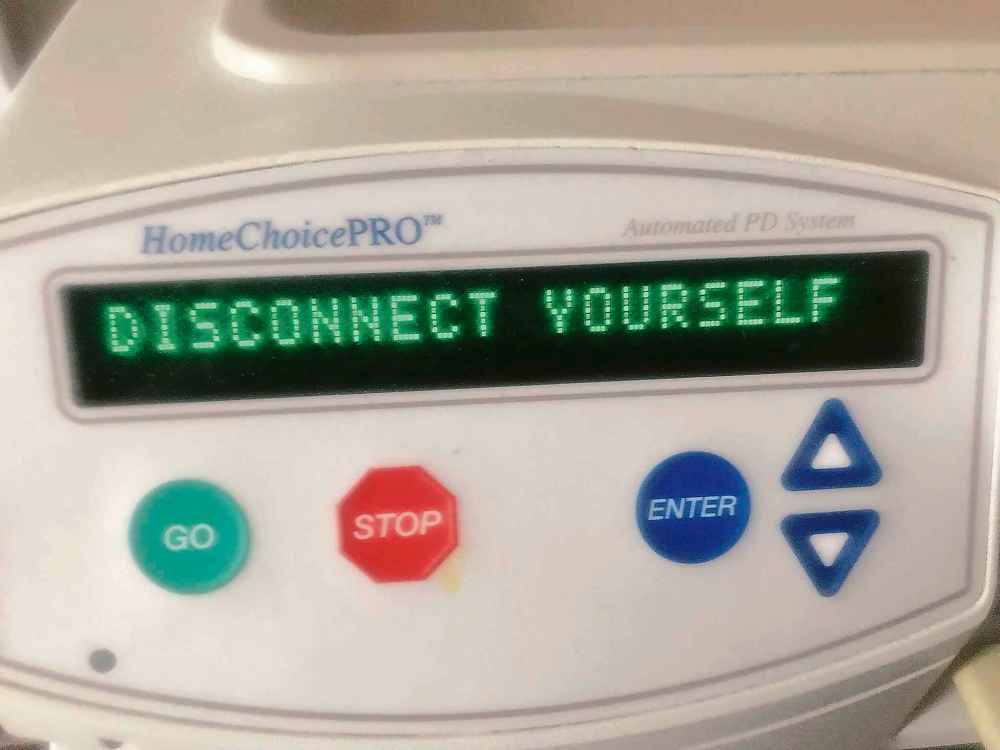

It was a longer trip than I’d initially feared, but I did, in fact, reach the end of the road in 2017; my kidneys could no longer function without intervention. Dreaded or not, it was better to be in a lifeboat with peritoneal dialysis than stuck on a sinking ship.

Accessing the lifeboat required minor surgery to insert a catheter in my abdomen, providing a port into my peritoneum — a membrane that lines the abdominal cavity. A dextrose solution, infused with minerals such as calcium and magnesium, are pumped through the port into the abdominal cavity.

From there, osmosis happens, and the good solution makes its way through the peritoneum and into the blood; the toxins in the blood go the other way, into the abdominal cavity. After a period, the toxins — just like urine — are expelled through the port, either into a vinyl bag to be disposed in the toilet, or in the case of the dialysis machine I used overnight, directly into the toilet via tubing.

Other patients require hemodialysis, which requires several visits each week to hospital for three- or four-hour sessions during which blood is removed a cup at a time, cleaned and returned.

Peritoneal dialysis gave me significantly more independence. The nephrology team at St. B said if my health remained stable (apart from my failing kidneys I was in decent shape), I could continue working full time as the arts and life editor at the Free Press and even take short vacations.

It went pretty well, allowing me to live a — significantly modified — sort-of-normal life. Grateful as I was, living on a lifeboat inevitably loses its lustre.

•••

At every visit to the St. B nephrology clinic one of the first questions I’d be asked was, “Have you got a living donor yet?”

Transplants are kidney-disease treatment No. 4. Healthy organs can come from a cadaver or from a living donor, usually a family member.

A transplant isn’t a cure, even in the most successful cases. Donated organs don’t last forever — but they are the best treatment for kidney disease doctors have come up with.

I come from a um… Small family (sorry). I have two older brothers who have their own health concerns. My mother, who had a long career as a nurse, was offended when she was told — in her 80s — that she was too old to be a donor.

My blood type is O-negative, which is all-star material as a donor, but bad luck if you’re a recipient. O-negatives are wild cards who can donate blood and organs to people with any blood type, but can accept donations only from other O-negatives.

The wait list for O-negative kidneys from deceased donors was five years when I was diagnosed in 2006; it’s now a decade.

•••

It’s tough to remain optimistic with those numbers staring you in the face.

I was feeling pretty low when I walked into the newsroom at the Free Press after one of my clinic appointments — I believe I’d just learned I’d be going on dialysis — and crossed paths with Jill Wilson, a friend and colleague, who had something to tell me and insisted I “be cool” about it.

She told me she was going to donate one of her kidneys to me.

It would be an understatement to say I was stunned. I couldn’t speak.

I’ve edited the newspaper’s Random Acts of Kindness feature many times over my more than 20 years here. The people who write those letters marvel over the generosity of strangers who stop to change a flat tire for them, or pay for the coffee for the people in the car behind them in the drive-thru, or turn in a dropped cellphone.

But a kidney? From Jill? For me? What could I have done to deserve this kindness? It was overwhelming.

•••

There are many hurdles to clear before such an incredible act of generosity begins to become a reality. I urge you to read Jill’s accompanying story (above) to get a sense of the process from a donor’s point of view.

All I had to do was remain in the lifeboat.

•••

Jill and I have been friends and co-workers for the better part of two decades and we share the same blood type. Unfortunately, a blood test revealed I had antibodies that would reject her wonderful gift.

It’s not you, Jill. It’s my incompatible antibodies.

Plan B: last winter we applied and were accepted into the Canadian Blood Services paired exchange program. Our biological details were plugged into a Canada-wide algorithm in March that would search for matches. The people in the program warned me not to get my hopes up because my antibodies limited me to just 36 per cent of the O-negative population. Nearly two-thirds of the potential donors weren’t available to me.

Don’t hold your breath, I thought.

What did I know? Someone from the program called a week later with the stunning news that Jill and I had been matched up in the exchange. I’d be getting a kidney from another selfless soul three months later.

Between the time I hung up the phone and the surgery, however, there would be more tests. And with each one I feared something would reveal itself to be an unsolvable problem that would leave me languishing in that lifeboat.

First there would be an ultrasound test. Not a big deal; I’ve had many of them over the past 14 years. This time, however, I was told the images weren’t clear enough to read accurately. My kidneys had so many cysts, they were obscuring the view of other cysts which, in a rare instance, could be malignant. A more frightening word than dialysis.

Off to the CT scanning department, I went. The techs couldn’t inject the dye normally used because it would wipe out what little kidney function I had left. Without the dye, the scan was inconclusive.

Anxiety? Well…

I was scheduled for an MRI. Most Manitobans wait months for one. Somehow I was scheduled in short order, late on a Sunday night after watching an episode of Game of Thrones. And although the techs couldn’t use the dye in this case, either, the scan was readable. There were no sinister surprises that would foul up things.

Relief? Well…

I was scheduled for surgery at Health Sciences Centre. The day couldn’t arrive quickly enough.

•••

When I checked in at HSC, the entire renal transplant team — including medical director Dr. David Rush — was there to greet me. I’d see a lot of Rush over the next few days; he’s one of Canada’s top kidney transplant nephrologists and is a spokesman for Manitoba’s growing transplant program. He’s also quite reassuring.

Kidney transplants are done on a regular basis at HSC and I’m told the procedure isn’t a particularly difficult one. Everyone’s confidence gives me confidence; by the time I’m wheeled into the operating theatre I have few worries. This is the moment I’ve been waiting for.

Next thing I know, I’m back in the ward and my new kidney is working. In most living-donor transplants the kidney begins passing urine the moment the clamps are released. I’m told it’s quite the sight for the doctors and nurses.

A catheter transfers my urine into a jug, which is monitored regularly. Everyone is excited while it quickly fills up. Rush tells me not to worry about the reddish hue.

“Right now it’s a rosé,” he says. “It’ll be a Chardonnay pretty soon.”

Four days later all the tubes, catheters and monitors are removed and disconnected. Rush removes the stitches from a vein in my neck and I’m sent home.

•••

I’m off work until mid-September, but I’m feeling better than I have in a long time. In a couple of weeks I’m walking around the neighbourhood and stopping regularly at the coffee shop a few blocks away. By August I’m itching to play golf, but my body isn’t ready for that sort of exertion yet.

My new regimen of anti-rejection and anti-viral drugs — my suppressed immune system means I have to avoid crowds at first — is working well and the initial waves of nausea are fading. My diet is suddenly upside-down; I can eat most everything and instead of restricting phosphates, I have to take supplements for a couple of weeks.

Winnipeggers often complain that summers are too short. It’s true… unless you happen to be recuperating from major abdominal surgery. There are only so many TV shows to binge, baseball games and movies to watch, books to read, crossword puzzles to decipher and neighbourhood strolls to enjoy before things become a tad tedious.

•••

I return to work Sept. 23. And the next step? I take the stairs to the third-floor newsroom. I did it before the surgery and I was gassed for five minutes afterward. This time? No problem. My new kidney is working as it should.

I feel like a new man at the age of 52, with a slowly receding bump on the left side of my belly where the new kidney resides, filtering my blood for many years to come, I hope.

I look back at the past 14 years and think the whole thing is a miracle: the doctors and nurses who got me back on my feet in 2006; the medical team that looked after me before and during dialysis; the people who helped me during and after the transplant; my friends and family, who cheered me up while they cheered me on; and living donors.

And Jill.

What do you say when “thank you” falls so far short?

Because of her I have time to come up with an answer.

alan.small@freepress.mb.ca Twitter:@AlanDSmall

Jill Wilson writes about culture and the culinary arts for the Arts & Life section.

Alan Small has been a journalist at the Free Press for more than 22 years in a variety of roles, the latest being a reporter in the Arts and Life section.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.