Rearing its ugly head New pilot program seeks to overcome stigma of STI testing as syphilis makes unwelcome return

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 20/08/2019 (2305 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It’s an old disease, thought to be wiped out.

And it’s making an unwelcome comeback.

The number of syphilis cases is growing by leaps and bounds in Winnipeg.

According to a Winnipeg Regional Health Authority internal memo, reported by media outlets this past spring, cases of the sexually transmitted infection (STI) are expected to exceed 600 by the end of the year. That’s up from 457 in 2018, Manitoba Health, Seniors and Active Living reports.

And it’s nearly six times the annual average from preceding years.

“This is 19th-century stuff,” says Dr. Andrew Lodge, medical director of Klinic Community Health.

Before antibiotics were invented, syphilis was a scourge. Untreated, it led to horrific outcomes, including dementia, hearing loss, facial deformities and a slow death.

Thankfully, syphilis has been treatable for decades with antibiotics; it was largely thought be wiped out as a result.

A bacterial infection, it was never completely eradicated and has recently become a growing health problem, in part because it had fallen off the radar for so long.

Part of the challenge is syphilis infects most individuals with few symptoms at first, other than a painless sore. As a result, it may go undetected for some time, posing particular dangers to the unborn children of infected parents, who can pass it on in utero unknowingly, causing serious congenital problems.

And health-care providers have seen more and more newborns affected by the disease, Lodge says.

“That’s something that a few years ago was virtually unseen, so much so we didn’t even learn about it in med school.”

It’s this revival of an old illness that is the partial impetus for a new pilot program launched by Klinic to bring testing for STIs to populations unlikely or unable to access conventional blood tests.

What is dried blood spot testing?

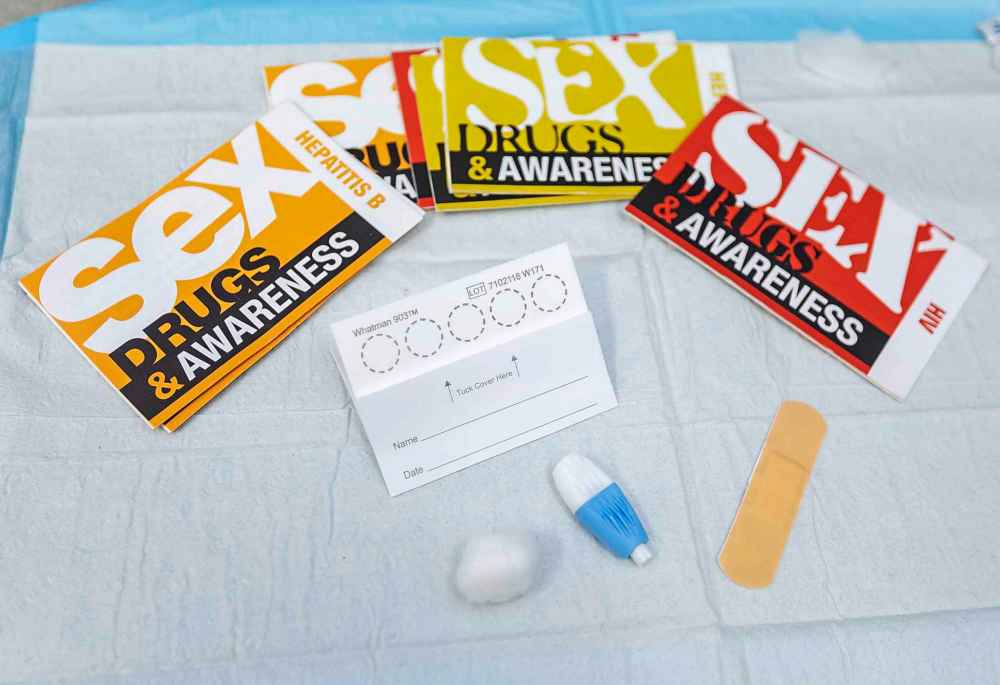

Dried blood spot — DBS — is a simple test and does not require a trained health-care worker to collect blood via finger prick. Drops of blood are smeared onto test circles on a piece of paper about the size of a business card.

Dried blood spot — DBS — is a simple test and does not require a trained health-care worker to collect blood via finger prick. Drops of blood are smeared onto test circles on a piece of paper about the size of a business card.

DBS is considered a much simpler test than blood drawn by a needle. Other advantages are less blood is required, and transport of samples needs no complex, special precautions or storage (i.e. it can be safely sent through the mail). Currently, DBS tests for HIV, syphilis, and hepatitis C and B. For each of these diseases, its accuracy is about 95 per cent or higher, says Dr. Andrew Lodge, medical director of Klinic Community Health.

Source: CATIE (Canadian Aids Treatment Information Exchange)

The initiative involves dried blood spot testing, or DBS for short. It’s an easy, low-cost test that individuals could very well do on their own without setting foot into a medical clinic. Lodge argues DBS could be an important tool in reaching at-risk populations for syphilis, HIV, hepatitis C and other disease.

Many parents are actually familiar with DBS; after the birth of a child, a health-care provider pricks the heel of the newborn and smears drops of blood on a test card.

“That’s typically the experience in Canada,” Lodge says. “But elsewhere, in Africa and Asia, it’s much more widely used (for STIs).”

For adults, the test involves pricking a finger with a needle and smearing the blood drops on a special paper test card, which is then sent to a laboratory to provide results.

DBS is considered accurate, he adds, and a good tool for individuals without direct access to lab services. Chief among them are those living in northern remote communities.

But the testing method could also help stem the spread of disease in the city among individuals often underserved by the health-care system.

“We’re basically trying to remove the walls of a quote-unquote clinic and allow people to test themselves.”

As Lodge further notes, the populations DBS could help most are those who typically do not visit clinics and are engaged in high-risk activities — sex-trade workers and injection drug users, for example. But DBS could also benefit anyone who may feel stigmatized visiting a clinic for an STI test.

“I think a lot of people probably feel that way, actually,” Lodge says.

So far the pilot has held one testing event in June on National HIV Testing Day, partnering with the community-based Indigenous organization Ka Ni Kanichihk.

Laverne Gervais, project co-ordinator with Ka Ni Kanichihk, says the non-profit participated in the initiative because DBS could reach some Indigenous individuals in Winnipeg who are reluctant to visit a medical clinic for a variety of reasons.

These individuals might include at-risk youth “who don’t trust the system, and often have been hurt by it,” she says, referring to health care, social services and other government services.

Gervais says it’s not uncommon for Indigenous people to have had negative experiences with health care, which can make them reluctant to seek preventative care, such as a blood test. What’s more, DBS could help decrease the spread of HIV and hepatitis C among Indigenous populations, who are over-represented among new cases in Canada.

Both Gervais and Lodge further add providing DBS involves an element of reconciliation, offering Indigenous individuals control over their health care because it allows them to get tested on their terms.

Gervais says this is potentially attractive for many Ka Ni Kanichihk clients, given their trust in the system may be tenuous, in part as a result of the ongoing effects of Canada’s long, tragic history of colonization, which has included guinea pig testing and forced sterilization of Indigenous people by the health-care system.

Today’s policymakers understand how this past negatively informs present care and are seeking ways to foster more positive engagement among Indigenous communities in the system.

Gervais suggests DBS is a step in this direction because instead of trying to get Indigenous people to come to health care, health care is going “to where people are at.”

In the near term, Klinic seeks to offer DBS at music festivals and other large public gatherings where it can reach higher risk individuals. People can get tested quickly — by a nurse, as required by current protocol — with samples then sent to a lab.

Long-term, Klinic’s aim is that DBS testing would be more easily available to at-risk populations who need and want it.

Several challenges exist, however, including how to provide followup for test results. In a recent statement to the Free Press, the provincial government noted DBS is an effective method to provide STI testing for hard-to-reach populations. Yet analysis of samples would involve more commitment of public resources. For example, the province notes a positive DBS result would require confirmation with a conventional blood test.

Yet while the province weighs its options, Klinic will continue to offer DBS.

“We’re hoping to do this more and more,” Lodge says. “We’re just not sure exactly how it will look and work yet.”

joelschles@gmail.com