Poignant, profound life lessons… from talking toys

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 28/06/2019 (2359 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Sitting at the multiplex last week watching Toy Story 4, my first thought was this: Considering this is a cartoon movie with the word “toy” in the title, there aren’t that many children in the audience.

Instead, there were a lot of people who would have been children when the first Toy Story came out in 1995. And there were even older viewers like me. I had young kids at the start of the franchise, and now, like the kids onscreen, they’ve left their toys behind and headed to university.

This franchise has always been about the passage of time, and there’s something poignant, powerful and fitting about seeing it playing out within a real-time context, almost 24 years after it began.

The Toy Story movies offer tons of child-friendly fun – appealing characters, inventive action scenes, humour — but for the audiences growing up or growing older along with these stories, they have also been about time and change, about loss, aging and, yes — in the wonderfully sobby Toy Story 3 — even death.

The Toy Story movies are based on the whimsical (and occasionally unsettling) idea that toys are sentient, pretending to be inanimate objects when humans are around but leading complicated emotional lives when unobserved.

For toys like Woody (voiced by the reliably steady and good-natured Tom Hanks), Buzz (Tim Allen) and Jessie (Joan Cusack), time seems to move at a different rate than it does for “their kids,” who grow up and forget their old friends, giving them away or dumping them at a garage sale or packing them up in boxes in the attic.

This frank acknowledgment of the passage of time has been one of the reasons this franchise has escaped the sequel curse. Rather than just repeating itself, mostly for a box-office payoff, Toy Story has moved along gently with the years, becoming better and deeper.

The series isn’t needlessly dark — underpinning its serious themes is a resonant, big-hearted optimism — but it has increasingly explored important, difficult human questions in ways that reach both adults and kids.

That’s another way this series works. Too often with the big studio movies, that “family-friendly” designation defaults to a bifurcated structure that offers fart jokes for the kids along with winking, sometimes slightly smarmy content for their parents.

Toy Story takes a more hopeful and generous approach, believing that really good material can work for children and adults at the same time.

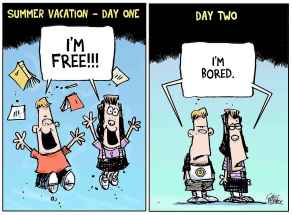

Children will instinctively grasp one of TS4’s main themes. Bonnie (Emily Hahn), the little girl who now plays with Woody and the gang, is anxious about kindergarten orientation, an event that for a fearful five-year-old represents the sudden acceleration of time and change and all those things over which she has no control. That’s why she clings so fiercely to Forky (Tony Hale), the googly-eyed arts-and-craft character she has created out of a spork and pipe cleaners and popsicle sticks.

For grown-ups, the anxiety is more diffused but just as difficult. While it never pushes the point too hard, Toy Story 4 is about Woody gradually letting go of control.

The series has always been a workplace comedy, with Woody having to come to terms with the fact that he’s no longer the man in charge.

First the competent Woody had to job-share with Buzz, who’s kind of adorably incompetent (and occasionally competent by accident). Now Woody’s plight suggests a bigger demographic shift, with quiet references to male leaders being replaced by women — significantly, Jessie gets Woody’s sheriff’s badge — and to baby boomers retiring and the younger generation stepping in.

There’s even a subtle comparison of Woody’s regular full-time job with the situation of Bo (Annie Potts), who seems to be in the 21st-century gig economy, toy-wise.

Toy Story’s quiet layers of subtext also include romantic love. There are references — some involving Keanu Reeves as a Canadian action figure called Duke Caboom — about getting over a break-up and learning to love again. There are little jokes about getting back into the dating scene after being on the shelf. (Like, literally on the shelf, in this case in a dusty antique store.)

And, of course, the movie is about parenting, offering a melancholy empty-nester parable about watching your kids grow up and grow away.

Woody, who’s already gone through this process with Andy, seems to be overcompensating with Bonnie — basically, he’s become the toy version of an overprotective helicopter parent. He frets about being helpless and useless, instead of realizing his kids are making their own way now and he needs to make his.

Dealing so poignantly with time and memory, Toy Story 4 delivers some paradoxical lessons about nostalgia. In a flashback montage, the movie suggests the sweetness of nostalgia and the cumulative emotional effect of four films that span two-and-a-half decades.

But TS4 also suggests that nostalgia can become a burden — whether that’s in terms of work, love, parenting or growing up — when it leaves us stuck in the past.

The story is about figuring about who you are right now, as Woody finally comes to realize.

In what feels like the final installment of a 24-year-old tale, Toy Story 4 acknowledges the power of nostalgia, and then — sadly, gracefully — lets it go.

Studying at the University of Winnipeg and later Toronto’s York University, Alison Gillmor planned to become an art historian. She ended up catching the journalism bug when she started as visual arts reviewer at the Winnipeg Free Press in 1992.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.