Neighbourhood watch WAG puts the focus on photographer, filmmaker John Paskievich, who has trained his illuminating eye on the people and places of the North End

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 27/06/2019 (2365 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

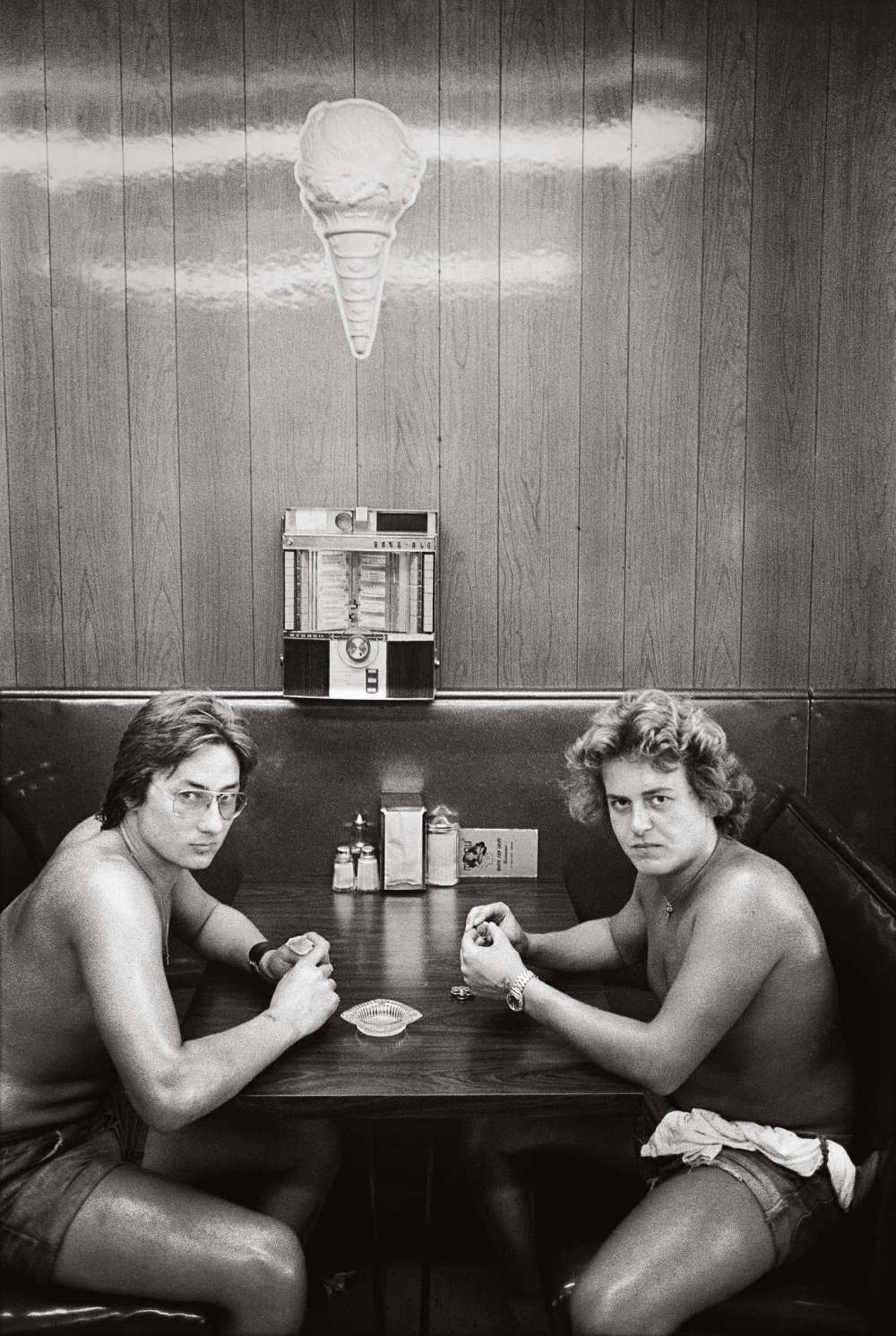

The North End has been John Paskievich’s stomping ground for decades. Though the filmmaker and photographer now lives in Wolseley, he grew up in north Point Douglas, on a short street named Lorne Avenue.

Art Preview

John Paskievich: The North End

● Winnipeg Art Gallery

● Opens June 29, runs until Nov. 3

As a child, Paskievich — who came to Winnipeg in 1950 with his Ukrainian parents, who had been in a displaced persons camp in Austria — played around the grounds of Vulcan Iron Works where, in 1919, workers demanded eight-hour days and a living wage spearheaded by the Winnipeg General Strike.

As an adult, after studying photography and film at Ryerson University in Toronto, he turned the lens of his Leica camera on the alleys, storefronts, parks and people of his neighbourhood.

That lens, and the benevolent eye behind it, captured black-and-white images of a largely unsung area of Winnipeg exposing, without judgment, both its unique charms and its ongoing struggles.

The Winnipeg Art Gallery is about to launch the largest-ever local exhibition of his work, a collection of 50 digital prints curated by Andrew Kear, the WAG’s curator of Canadian art.

The art of labour

John Paskievich’s The North End exhibition at the WAG is timed to coincide with the centenary celebrations of the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike, but the photographer’s work is not explicitly about labour, though it often prominently features the working people of a neighbourhood that historically was home to a pro-strike population.

Andrew Kear, who curated The North End, is the Winnipeg Art Gallery’s head of collections and exhibitions and curator of Canadian art. He recognizes the somewhat tenuous link between the strike and Paskievich’s work, and he has an explanation: there is precious little visual art related to the event.

John Paskievich’s The North End exhibition at the WAG is timed to coincide with the centenary celebrations of the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike, but the photographer’s work is not explicitly about labour, though it often prominently features the working people of a neighbourhood that historically was home to a pro-strike population.

Andrew Kear, who curated The North End, is the Winnipeg Art Gallery’s head of collections and exhibitions and curator of Canadian art. He recognizes the somewhat tenuous link between the strike and Paskievich’s work, and he has an explanation: there is precious little visual art related to the event.

Photographs of the parades, protests and conflicts abound, including the famous image of a streetcar toppling on Main Street by L.B. Foote, but Kear says that kind of documentation of social history is best presented by museums, rather than art galleries.

Kear first recognized the dearth of art surrounding the Winnipeg General Strike in 2012, when the gallery was celebrating its 100th anniversary. As he went through the archives, he realized the anniversary of the strike was also approaching and began searching for works for a future exhibition.

In 1919, the WAG was located at what’s now William Stevenson Way and Main Street, in a building that no longer exists called the Industrial Bureau.

“This is the place that was built in 1912 to house not only the Winnipeg Art Gallery and what would become the Manitoba Museum, but also a kind of a place to raise awareness, sell, advertise all the economic opportunities the city had to offer,” Kear explains. “It was set up by a lot of people in the business community and was very closely connected with people in government.

“So right off the bat I was like, ‘Oh, that’s interesting, that the city’s art gallery would be architecturally embedded in the space that was pretty much set up by commercial interests. And of course the Industrial Bureau in 1919 would become the place where the (Citizens’) Committee of 1000 would meet — we have images of the people gathered outside; it was a place of protest.”

The Citizens’ Committee of 1000 was the group of far fewer than a thousand businessmen and politicians who worked together to break the strike, enlisting the help of the federal government.

“The next question was, what in the WAG’s collection or archives relates to the strike?” Kear says. “Given this kind of coincidence of history, I thought, OK, there’s got to be something.

“Silence. Absolute silence.”

The reasons are threefold, he says. First, the WAG was not a collecting institution in its early years; its collection at the time would have been works donated by the wealthy elite, not purchases from rabble-rousing artists.

Second, it was likely not in the best interest of a local artist who wanted to exhibit at Winnipeg’s only public gallery to make work representing an event that created a great deal of turmoil for the business interests the WAG was entwined with.

“Third, in the postwar era, the idea that art can do something that brings us closer to life, rather than something that is separate from life, begins to change, Kear explains. “You have the idea that art can be political. In the early years of the 20th century, that idea is not commonplace.”

— Jill Wilson

The exhibition, which opens June 29 and runs until November, allows Paskievich to debut some newer images he hadn’t yet found time to print, owing to some film commitments.

“The WAG said they would need prints, so I contacted (Winnipeg artist) William Eakin — Bill — who knows his way around the old school and the new school and he’s printing them,” Paskievich says, adding that the digital prints have a different esthetic than those he develops in his darkroom.

“Digital prints are an approximation of the silver halide,” he says. “Those prints have silver in them, they’re metallic and they reflect light.”

Nursing a mug of tea with honey in an Exchange District coffee shop, he mulls over the ways the North End has changed since he first began practising street photography there in the 1970s.

Paskievich, director of the National Film Board documentaries Unspeakable and Ted Baryluk’s Grocery, among others, still visits the neighbourhood with his Leica, but he says the reception is more guarded and less welcoming than it once was.

“It’s getting to be a rough place where I have been accosted a few times, not a nice way,” he says, adding that the attitude toward a man with a camera is quite different these days.

“Is it ever! Oh man, is it ever! You get questioned more, you get stopped by the police. You’re outside a schoolyard and you’re taking pictures — not necessarily of the kids — and it happens to be recess, and the school monitors say you have to go to the principal’s office,” he says, laughing.

He also admits that the relationship between him and his subjects has become more complicated since he moved out of the North End and can no longer claim common ground.

“I’m an outsider now, for sure, and I’ve been described as one in very colourful ways,” he says.

The demographic has shifted, too, over the years. Long known as a working-class area that was traditionally the first stop for newcomers and immigrants to the city, it’s become an even tougher place where poverty and disenfranchisement are prevalent.

“The North End is now another issue: the ghettoized, marginalized and Indigenous poor. It’s a whole other issue,” he says. “My intention is not specifically to raise that point, but it shows up, I think, in the pictures.”

Paskievich’s work, last collected in a beautiful volume from University of Manitoba Press called The North End Revisited, is not political, though it can be tempting to interpret it as such.

Though the photographs are named only for the street or intersection where they were shot, they mostly feature human subjects, often those unlikely to be captured in traditional portrait format.

His compassionate work, with its strong sense of place, confers weight and a sense of narrative to unheralded moments in a gritty neighbourhood that’s been overlooked and underestimated.

He captures people expressing jubilation, affection, grief and boredom. Some are caught in a moment of vulnerability, others smile broadly for the camera. Still others aren’t aware they’re in the frame, going about their business of gardening, chopping wood or riding the bus.

“It what’s used to be called — and you don’t hear the word anymore in photography — it’s humanist,” he says of his work. “And you can be a conservative humanist or a liberal humanist.”

jill.wilson@freepress.mb.ca Twitter: @dedaumier

More of John Paskievich’s work

John Paskievich has been photographing Winnipeg’s North End for decades. Here’s a small selection of work from two books, The North End and The North End Revisited.

.jpg?w=1000)

.jpg?w=1000)

.jpg?w=1000)

.jpg?w=1000)

.jpg?w=1000)

.jpg?w=1000)

.jpg?w=1000)

.jpg?w=1000)

.jpg?w=1000)

.jpg?w=1000)

.jpg?w=1000)

.jpg?w=1000)

.jpg?w=1000)

Jill Wilson writes about culture and the culinary arts for the Arts & Life section.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.