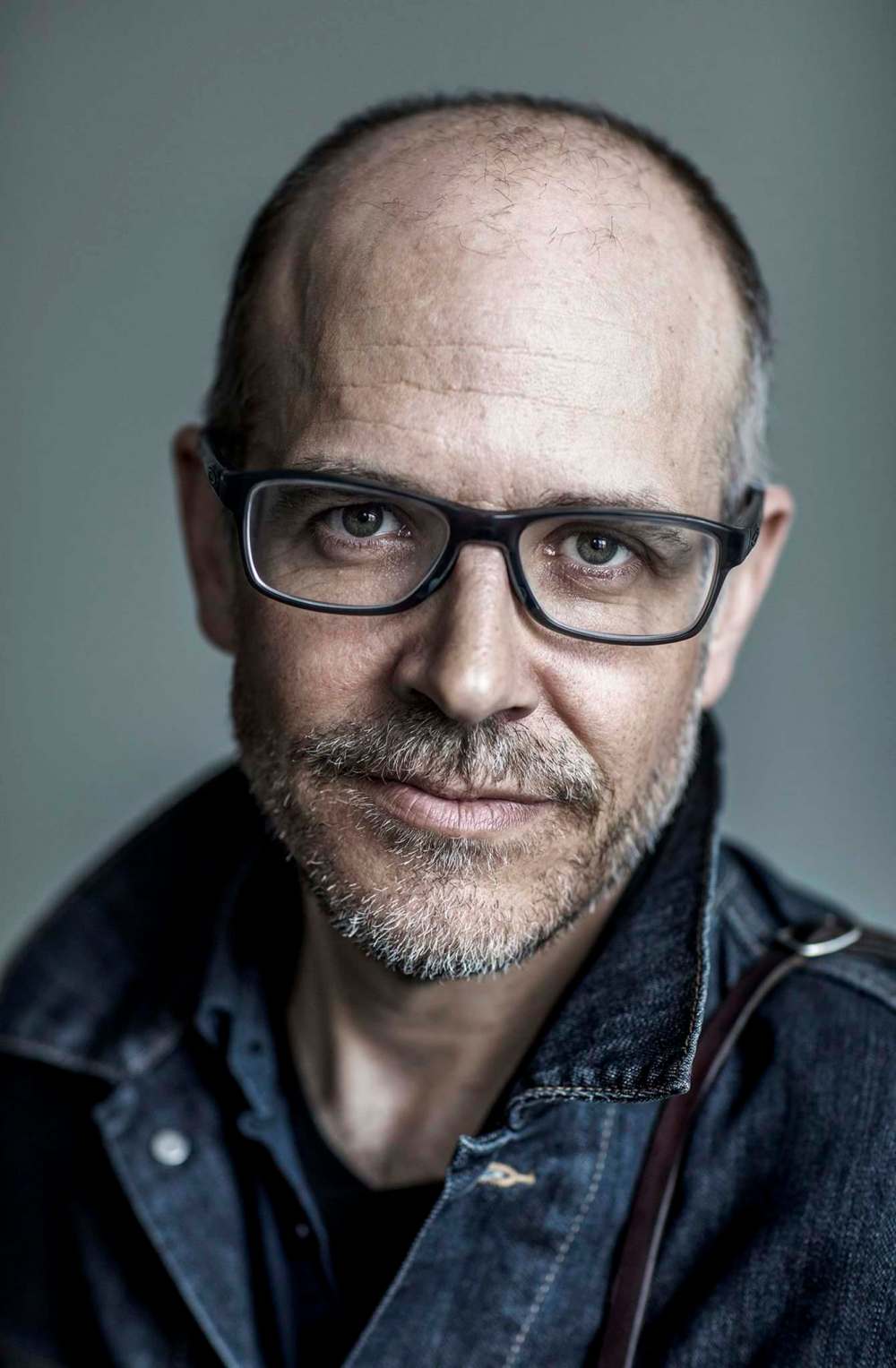

Portraits of a crisis Former Winnipeg photojournalist's pictures bear witness to atrocities committed against Rohingya

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 13/06/2019 (2371 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Kevin Frayer’s photos are frequently hard to look at. But it’s harder, still, to look away.

Event preview

Time to Act: Rohingya Voices

● Canadian Museum for Human Rights

● Opens Saturday, to April 2020

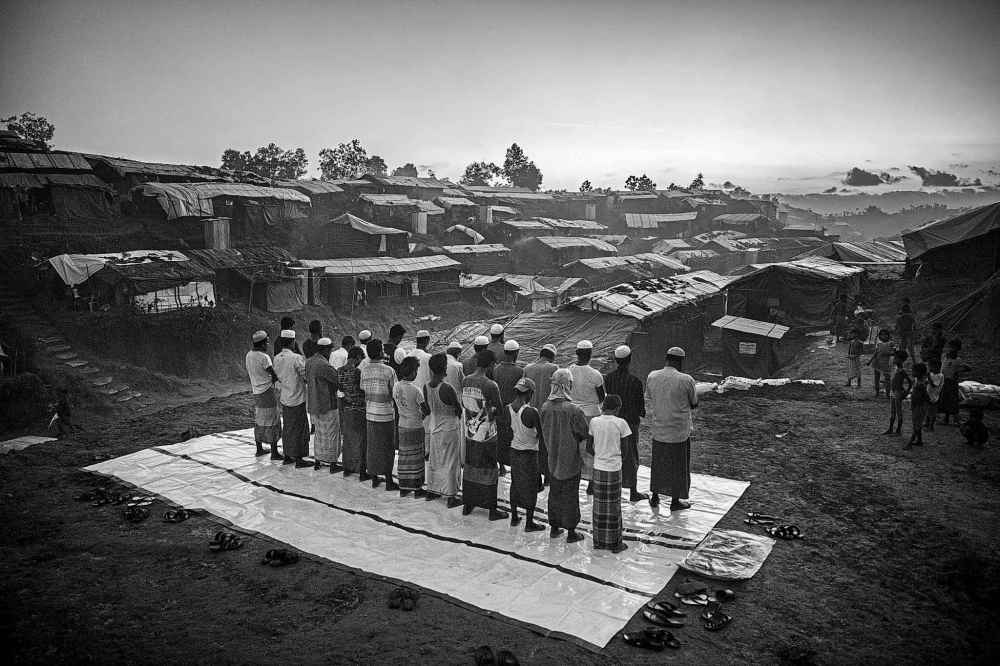

Thirty of the award-winning photojournalist’s striking black-and-white images documenting both the exodus of hundreds of thousands of Rohingya refugees fleeing ethnic cleansing and violence in Myanmar as well as the ongoing humanitarian crisis in the refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, anchor Time to Act: Rohingya Voices, a powerful new exhibition opening Saturday at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights.

For decades, the government of Myanmar, a majority Buddhist country, has denied the Rohingya people, largely Muslim, their rights, citizenship and humanity through acts of erasure and outright violence. The exhibit, which runs until April 2020, seeks to restore that humanity and dignity to the Rohingya people. (Previous to this, the CMHR dimmed the portrait of Myanmar leader Aung San Suu Kyi, who has been criticized for her failure to condemn the violence against the Rohingya people.)

“That’s coming through the exhibition everywhere, including the title,” says Jodi Giesbrecht, director of research and head curator. “So Rohingya Voices, we really wanted to emphasize agency of the Rohingya, so whether it’s through speaking out about the genocide or raising awareness not just in Canada but on a global scale. Of course, we wanted to portray the depths of violations and the severity of the genocide, but we didn’t want to leave the story with victimization. We really wanted to emphasize exactly that, Rohingya voices.”

That meant including Rohingya people in the curation and creation process. The CMHR worked with Frayer, a former Winnipegger, on photo selection, but it also enlisted the perspective of a panel of Rohingya Canadian community members, many of whom are former refugees.

When it came to the photo presentation, “we started to explore how we could make them larger than life to make the more immersive,” says Robert Vincent, manager of design and production. Instead of a traditional wall hanging, they opted for projections on large scrims — and because the photos are deliberately in your face, great care was taken in their selection. As Vincent points out, when you have a photo projected on a 12-by-10 foot screen for two-plus minutes, you have to mindful of its content.

“We’ve tried to strike a balance between confronting how graphic the situation is with representing people in a way that underscores their dignity,” Giesbrecht says. Frayer’s photos do a lot of that work themselves; his images, even the difficult ones, are compassionate as opposed to exploitative. (In addition to Frayer’s professional photographs, the exhibit will also feature colour photos snapped by community members.)

Time to Act: Rohingya Voices is not a straight-ahead photo exhibit, however. Giesbrecht’s team also conducted 23 oral-history interviews with members of the Rohingya Canadian community, travelling all over Canada and gathering more than 60 hours of footage.

Instead of putting together a documentary-style audio-visual production, the CMHR decided to use that footage to create an innovative interactive experience.

“Basically, it was, ‘What does it look like if you could ask an exhibit a question?’ This allows you to literally do just that,” says Scott Gillam, manager of digital platforms. “When we think about using Siri or using Google Assistant, people are using voice assistants more and more, so this opened up an opportunity for us to connect visitors to the subjects in a completely different way.”

The Rohingya interactive exhibition allows visitors to ask questions from a series of prompts. If you ask, for example, ‘How is your life in Canada?’ you will hear from one of 12 Rohingya Canadians included. It almost feels like you’re FaceTiming with them, which adds a layer of intimacy and immediacy. Elsewhere, the museum also worked with 3DPhotoWorks in New York, which transforms photographs into tactile, three-dimensional topography, allowing visitors with no sight or low sight to view a photo with their fingertips.

Giesbrecht acknowledges the challenges that come with curating an exhibit about a humanitarian crisis that is still unfolding. To that end, the CMHR has put together a curated and vetted resource guide — including journal articles, presentations, music and government reports — for visitors who are interested to learning more outside of the gallery.

“There’s so much fake propaganda and all kinds of hateful things out there about the Rohingya, so it was really important to us that we be that source of credibility,” she says.

Time to Act: Rohingya Voices serves as an example of how a modern museum can address and react to current events.

“It’s not the only instance of an ongoing atrocity, but it’s one way for us to examine this particular atrocity, but also examine broader conflicts of war, migration, displacement,” Giesbrecht says. “The refugee camps in Bangladesh where the Rohingya have been displaced to are the largest in the world. There’s almost one million people in these camps. It’s an issue the whole world needs to turn its attention to.”

jen.zoratti@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @JenZoratti

Jen Zoratti is a Winnipeg Free Press columnist and author of the newsletter, NEXT, a weekly look towards a post-pandemic future.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.