Sun, songs… but no bongs Manitoba's restrictive cannabis laws will be an expensive buzzkill for recreational weed users ticketed at summer festivals

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 31/05/2019 (2387 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

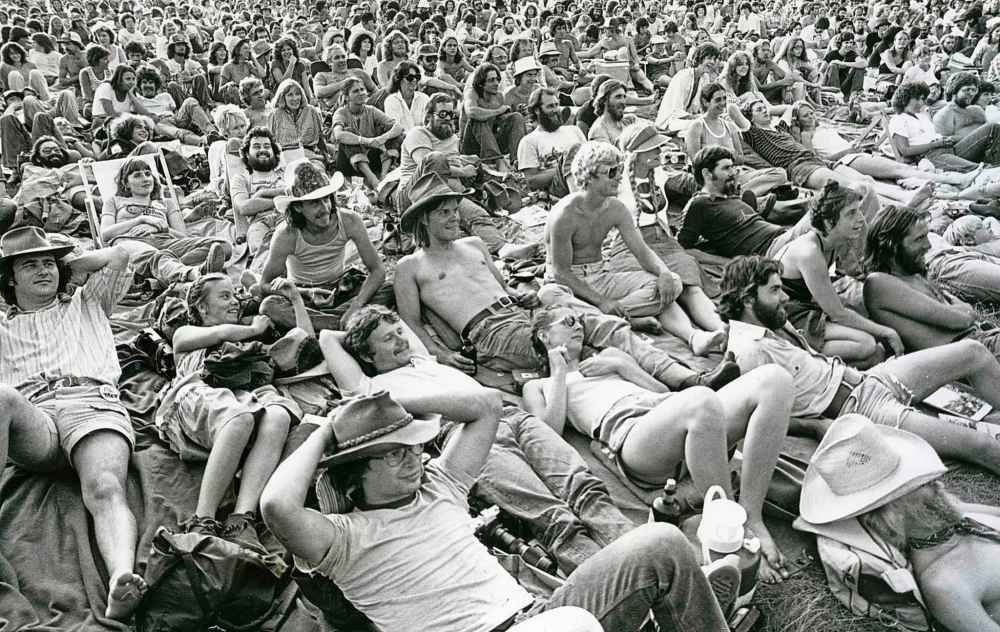

If you want to volunteer with the Winnipeg Folk Festival, you need to sign up for a work crew. There’s the photography crew, the site-safety crew, the box office crew, the “shleppers” crew, the first aid crew, the green room crew, and so on.

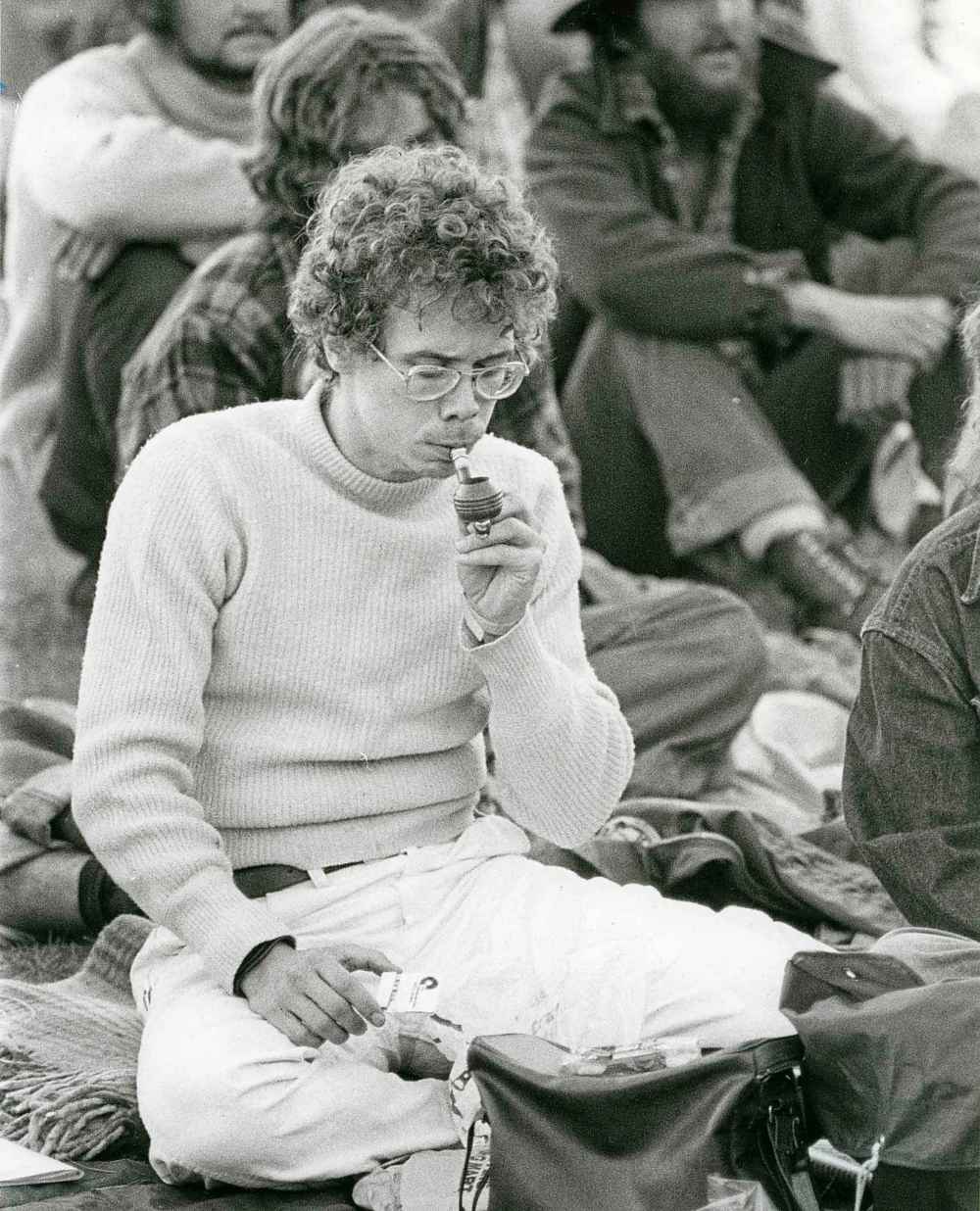

But in the festival’s early years during the 1970s, folk fest volunteers could join another: the joint-rolling crew, whose solemn task was rolling up cannabis cigarettes for after-parties at Winnipeg’s old International Inn.

“We put cups of joints on every table at the party,” folk fest founder Mitch Podolak recalls.

“What we were trying to do was just entertain the artists when they came to town. Some of them wanted hard drugs, and we said no.”

It wasn’t just performers who were lighting up joints after hours, of course.

“I saw the police report from the sergeant in Oakbank, and he actually used the quote that, ‘the air turned blue,’” Podolak says, laughing as he reminisces about weed at the inaugural festival in 1974.

“There used to be guys who used to run shops out of the parking lot. They were selling out of cars. Somebody had a bar out there too, selling mixed drinks. There was a lot of stuff that we couldn’t control, and didn’t try to.”

Decades later, less than a year after Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s Liberals legalized and regulated recreational marijuana, cannabis use will remain illicit at this year’s festival. Even with the old federal pot prohibition repealed, festival organizers can’t permit consumption on-site during the four-day event at Birds Hill Provincial Park; Manitoba’s Progressive Conservative government has expressly forbidden smoking or vaporizing cannabis in provincial parks. Anyone caught doing so is hit with a $672 fine.

“So, in some ways, it’s actually more illegal than it was before,” says festival executive director Lynne Skromeda. “Because there is a heightened sense, I think, towards what people should and should not be doing.”

The province has implemented a ban on smoking and vaporizing cannabis in any outdoor public place, including sidewalks and streets, parks and beaches, restaurant patios and outdoor entertainment venues. The rules are tougher than the rules for tobacco smokers, who are forbidden from smoking cigarettes and vaping e-cigarettes only in enclosed public spaces such as office buildings, the common areas of residential buildings, bus shelters and public vehicles.

Skromeda made clear folk fest volunteers and staff won’t be on the hunt specifically for pot smoke, and aren’t responsible for enforcing Manitoba’s consumption laws. The festival’s plan is to treat marijuana smokers the same as cigarette smokers, and ask them to move away from the rest of the crowd to avoid bothering others. Skromeda doubts it will be an issue, since the folk festival crowd tends to be well-mannered.

“These aren’t people who are creating a huge ruckus… our intention is not to vilify anyone or to ruin anybody’s experience,” she says. “But I think people just need to be smart about it.”

And at this year’s festival, that might mean dodging law enforcement; the RCMP will be on hand, along with provincial park patrol officers. Both have the power to ticket anyone daring to spark a joint, although an RCMP spokesperson wrote that officers “use discretion based on the situation and circumstances.”

“We want everyone to enjoy themselves at these events but we do like to remind people to be responsible,” they wrote.

● ● ●

Other Manitoba music festivals are also waiting to see how the province’s new laws will play out. Rob Waloschuk, general manager of Dauphin’s Countryfest, says he’s occasionally caught a whiff of weed in the air at past festivals, but doubts it will be a huge issue at this year’s event.

“(It’s) one of those things where, you’re not allowed to smoke (tobacco) in the public confines of our event, so that rule will apply obviously to cannabis, as well,” he says. “My opinion is, they’ll be asked to stop it, put it out, take it where you can actually legally smoke it.”

A similar approach will be taken at the TD Winnipeg International Jazz Festival, says Jazz Winnipeg executive director Lynne Stefanchuk. The festival straddles private venues across Winnipeg, but revolves around the Cube Stage in Old Market Square, a city park temporarily upgraded with licensed beer gardens.

Before legalization, Stefanchuk says, she’d sometimes notice jazz fest guests sneaking a joint in nearby Exchange District alleyways. This year, she expects the festival’s private security to treat cannabis smoke in licensed alcohol areas as a minor nuisance on par with cigarette smoking, although Winnipeg police officers who patrol the park will have the power to issue tickets.

As far as the festival is concerned, Stefanchuk adds, it’s perfectly acceptable for guests to use cannabis at home and show up buzzed for a performance, as long as they’re travelling safely.

“We’re selling people beer, it’s going to make them a little bit intoxicated, but we need to make sure that they’re not getting to the point where they’re a danger to themselves or others…. From our perspective, the same applies to cannabis,” she says.

Waloschuk, Stefanchuk and Skromeda all say their events would consider the idea of cannabis sales and consumption areas in the future if Manitoba law was to permit it.

But for now, Skromeda hopes media coverage of the provincial law will mean people at the folk festival won’t be too surprised that they can’t legally pass the dutchie. Even if ticket-holders haven’t heard about the laws already, Skromeda says the festival is taking steps to remind them of the rules.

“It’s been a learning curve for everybody, but again, I don’t think that the primary reason for people to come to folk festival is to worry about smoking a joint while they’re experiencing the festival itself,” she says.

● ● ●

Other Canadian music festival operators have the opposite expectation, and are betting that explicitly cannabis-friendly music festivals will be big business in years to come.

Murray Milthorpe is chief experience officer of the Journey Cannabis & Music Festival, which will be held in a conservation park in Vaughan, Ont., in August. He sees it as a chance to connect cannabis consumers with legal cannabis brands, all within the context of a music festival — and he’s confident festival-goers will want to spend their time and money on the event.

“We’ve been doing a lot of research over the past number of months ourselves, from the consumer standpoint, as well as from the (licensed producers), and there’s a huge lack of understanding and opportunities within this cannabis sector,” says Milthorpe.

“Obviously it became legalized, but the government restrictions in being able to enable a consumer to understand and engage and connect is where the weakness really lies.”

Milthorpe describes the Journey festival as an opportunity for Canada’s legal producers to directly talk to consumers without violating the federal government’s strict laws on cannabis-related marketing. (No one under the age of 19 will be allowed in, so there’s no risk of illegally promoting weed to youths.)

‘Obviously it became legalized, but the government restrictions in being able to enable a consumer to understand and engage and connect is where the weakness really lies’–Murray Milthorpe, chief experience officer, Journey Cannabis & Music Festival

“They can showcase their growing methodology, they can talk about the different strains, they can talk about a number of different factors that differentiate that (producer) versus another,” he says.

One thing the festival can’t offer is legal marijuana sales; cannabis sales licences are still in short supply in Ontario, and the host city of Vaughan opted out of allowing legal sales entirely. For now, it’s a bring-your-own-cannabis event.

Consumption will be permitted at the festival in line with Ontario law, in designated smoking areas Milthorpe promises will be a step up from the average smoke pit. Otherwise, the festival is trying to entice guests with art installations, cannabis-themed educational talks and music. Milthorpe says he and his colleagues hope to roll their cannabis festival out to other provinces, where laws permit.

The Journey festival isn’t the only music event outside of Manitoba to embrace legal consumption this year. The Edmonton Folk Music Festival is planning a cannabis smoking zone, as is the Calgary Folk Music Festival. The Ever After Music Festival, an electronic dance music event in Kitchener, Ont., is allowing people to take and consume limited amounts of marijuana in the form of pre-rolled joints.

Canadian Live Music Association president and CEO Erin Benjamin, who represents at least 100 Canadian music festival operators, says some of her members are definitely keen on finding a way to involve marijuana in their events.

“Look, there’s a reality about music festivals, and that is that they are a place where cannabis has been consumed since music festivals were invented,” she says.

Like Milthorpe and the Journey festival operators, Benjamin sees music festivals as a natural partner for a federal government that’s keen to boost the legal cannabis market over the black market and promote safe, responsible adult consumption.‘Look, there’s a reality about music festivals, and that is that they are a place where cannabis has been consumed since music festivals were invented’–CEO Erin Benjamin, Canadian Live Music Association

“(Live) music spaces are a really smart space to raise awareness, to educate the public, and we’re a smart partner in terms of making sure that legislators and Health Canada and others can reach a key and core demographic to help everyone understand what compliance looks like.”

Still, Benjamin expects it could take years for cannabis to achieve the same status as alcohol at Canadian music festivals, where festival-goers can choose between the beer tent or the cannabis cabana and buy and consume marijuana on-site without breaking the law.

“I don’t think it’s five years from now, I think it might be a little longer, but absolutely.”

•••

“I don’t know if there’s a clean answer to how long it will take” for cannabis to achieve parity with alcohol at music festivals, says Dan Malleck, an associate professor of health sciences at Brock University who researches government regulation of drugs and alcohol.

As far as governments are concerned, Malleck observes, legal marijuana could be shoehorned into two existing regulatory models for drugs: the model for alcohol, which is concerned about that substance’s intoxicating effects, and the regime for tobacco, which is concerned about second-hand smoke. Breaking free of those paradigms “would take people observing that it’s not a problem, and that regulation is better than prohibition,” he says. But for now, the default government position is often that “anything that is smoked must be bad for you.”

“I don’t think that’s right, I don’t think that’s true,” Malleck says. “But also, I think people err on the side of — I don’t even want to say caution — on the side of prohibition, right? Because it’s something new.”Tickets for public cannabis consumption in Manitoba have been relatively uncommon

Even with the prohibition on public cannabis smoke and vapour in Manitoba since legalization, tickets for public cannabis consumption in Manitoba have been relatively uncommon. The province said it has no cannabis infractions to report in provincial parks between legalization on Oct. 17, 2018 and May 15, a period when most parks were closed. Park officers issued 22 open alcohol infractions over the same period. One eviction for cannabis smoke occurred at Spruce Woods Provincial Park over Victoria Day long weekend.

Manitoba RCMP report issuing 29 provincial cannabis consumption tickets between legalization and May 21. Just one was for public cannabis use, and the remaining 28 were for cannabis consumption in a vehicle. Winnipeg police said they were unable to provide statistics on cannabis consumption tickets.

Manitobans who want to use marijuana at music festivals do have one legal option, at least for now: the ban on public consumption doesn’t currently cover cannabis-infused food.

Commercial sales of cannabis edibles are still waiting on federal government regulations, but homemade edibles are perfectly legal and functionally similar products — ingestible oils, capsules and oral sprays — have been available at licensed cannabis stores for months already. (A spokesperson for Manitoba Health said the provincial government is waiting for Health Canada to release its regulations for cannabis edibles before considering where those products fit into provincial cannabis consumption laws.)

But at the end of the day, marijuana-and-music lovers such as folk fest founder Mitch Podolak simply won’t be allowed to smoke a joint — or puff a smokeless vaporizer — at a music event in any public place in Manitoba.

Podolak says that won’t stop him from enjoying this summer’s edition the same way he always has.

“I mean, I don’t run around smoking pot everywhere, but I smoke it at the folk festival,” he says. “I always have, and I always will.”

Most Manitobans don’t use marijuana, but users such as Podolak aren’t uncommon either: in the first quarter of 2019, 13 per cent of Manitobans age 15 and older used the drug at least once, Statistics Canada says.

Still, Podolak says he’s observed a decline in marijuana use at the Winnipeg Folk Festival since those heady early days.

“I’m not a spring chicken. But people who were 40 when I started the folk fest, were very much products of the ‘60s, right? (They) are now mostly dead from old age,” he says.

“That’s what the difference is. This last generation is just a little milder than my generation was.”

solomon.israel@theleafnews.com

@sol_israel