Riffing on revenue Musicians are singing sad songs about the industry's shift away from album sales to streaming services

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 24/01/2019 (2605 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

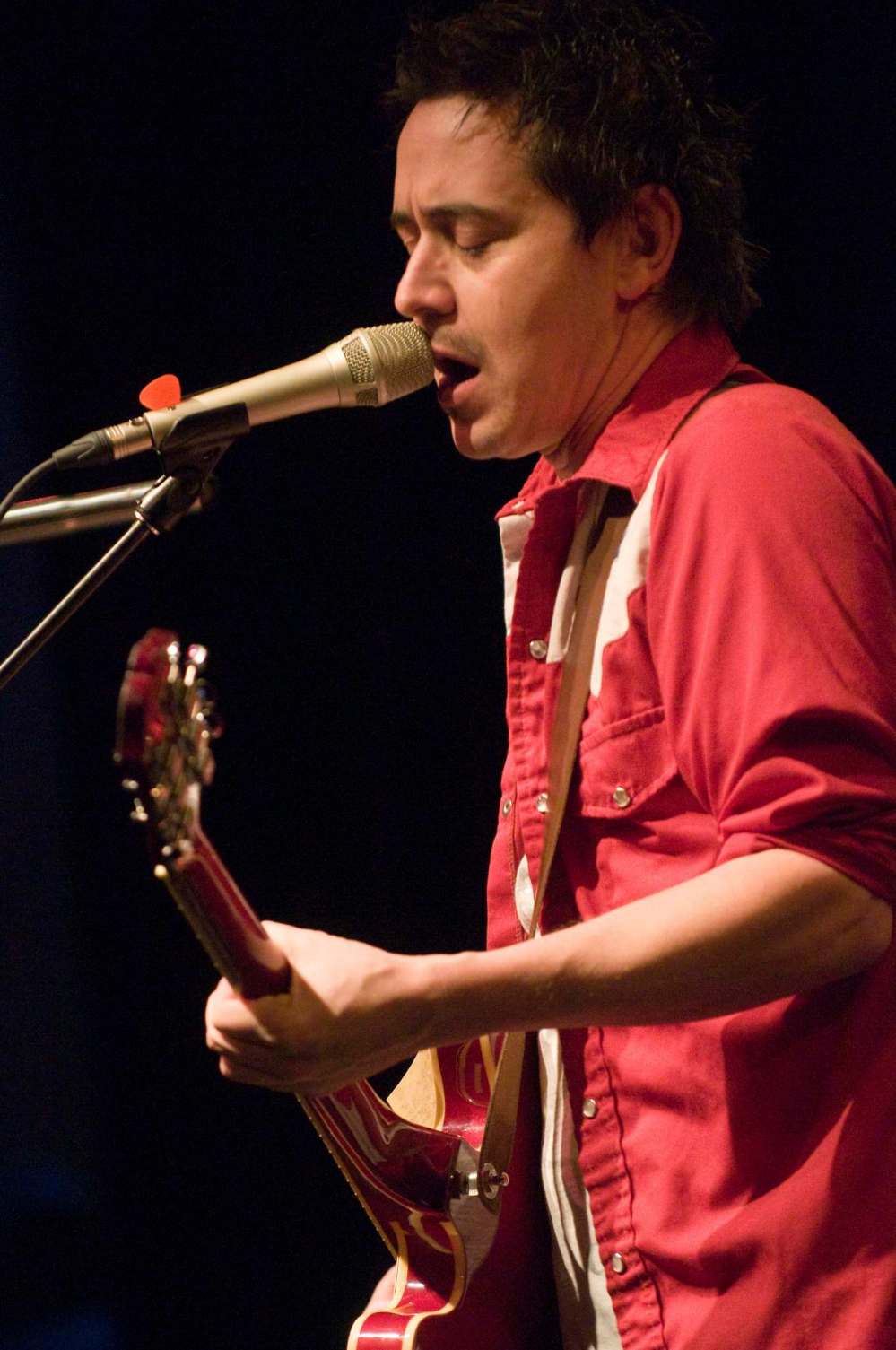

In November, Canadian musician and producer Danny Michel wrote a lengthy post on Facebook about how streaming services have drastically affected his income in a negative way.

He detailed the math of his record sales to this point, his current sales and the amount of touring it would take the make up the large gap. He explained he loves music and hard work, but the expectation to continue to run his career even more like a business than in the past, but having no money to do it, is weighing on him. He said because of this, some friends who are longtime musicians are no longer playing, or are looking for exit strategies.

“That (post) came from driving home from shows where I was backstage chatting with musicians who were all talking about that and musicians who I watched every week, two people I know who are fabulous musicians were telling me that they had just sat at a desk for their first job interview ever, and they’re like 45 years old and I thought, ‘Wow, this is real now, this is happening now, people I played with no longer play,’” Michel told the Free Press via phone from his Ontario home.

“And maybe this is too personal, but my accountant called me and said, ‘What’s going on this year?’ And I’m like ‘What you do mean?’ And he’s like, ‘You made way less money than you did last year.’ And we sat down and went through all the numbers and figured out, like, was I playing less? No, it was album sales, they were gone, so that was another thing that just… and that was just actual evidence, on paper, math, it was evidence that 2018 was when it changed. And five years before that, I consistently sold ballpark around the same amount of albums.”

While he may sound like he’s complaining, Michel made it clear he fully understands it is his decision to be a musician, knowing fully how jarring the ebbs and flows can be when it comes to income. His songs paid for his home and have given him a comfortable life; his main point is the music industry has become incredibly difficult to survive in and that for the first time in his more than 20-year-career, he noticed a substantial dip in revenue.

The post, which has been shared almost 6,000 times, sparked some candid discussions among musicians and others in the industry; some agree with Michel and some don’t, but one thing every opinion seems to confirm is that musicians are working more and harder than they ever have before.

This year, Manitoba Music’s annual January Music Meeting — an industry conference which began Thursday and runs until Sunday and brings industry and artists together in Winnipeg — is focused on how to turn that increased work into increased payoff, so that younger and up-and-coming artists start in the industry with a better knowledge of how to navigate it.

“We really want to help artists and folks in the industry have the biggest impact for the work that they’re doing, how to reach the biggest number of people for the work that they’re doing. So much creative work goes into making music and our goal is to really help folks think strategically about it, to make the most of the work they’re already putting into it. And I think to think about who else is out there in the industry that can help them,” says Sean McManus, executive director of Manitoba Music.

McManus believes there are a few contributing factors that have led to the radical shift in how the business side of the music industry runs from the perspective of an independent artist; in the past two or three years, streaming has become the way people consume music on a global level, which, as Michel and many others have learned the hard way, does not kick back the same revenue as traditional album sales did in the past. The second change is that social media has become the main mode of marketing.

“I think those two factors together have really not only increased the workload but in a lot of ways just really changed the way of working and the business proposition for artists in general,” McManus says. “I think that with streaming you have now a distribution world that’s really based around singles, so even when you have an artist making albums, they need to think about the marketing rollout from a singles point of view, and that means a much longer rollout, much more strategic, many more pieces in terms of video content and things that will go along with that.

“And that’s the same in terms of the social media environment, it demands that continual production of content and so you have the artists that are doing well in that environment are the artists that can really creatively and without a huge amount of expenses, create video content and create new content for fans. And the two sort of go hand in hand.”

These factors, as well as the need to increase time on the road to earn a sustainable living, is part of the reason longtime musician Matt Worobec recently decided to take a step back from a full-time music career and instead opted for a traditional 9-5 job.

“The reason I stepped away from music as a full-time thing is that the industry is so in flux that even the goal of making a comfortable, not even comfortable, like a $35,000-$45,000 a year living off of music, that was even difficult at times,” says Worobec, 38, who has fronted bands such as Tele and Alyx Knight as a guitarist and vocalist.

“And starting a young family, wanting to just be home a little bit more. I love to tour and love to travel but to make the kind of money I was hoping to, to just live a comfortable life, I was going to have to be on the road for 250 days a year or something like that. That was my personal thing, but the state of the industry was so in flux that I could no longer take the risks that I could in my early 20s.”

Worobec entered the music industry in 2003, right around the time music streaming was in its infancy with websites such as Myspace, and shortly after file-sharing giant Napster had ceased operations. He has seen the transition and felt the changes first hand, and says it’s a totally different industry now than what he came into.‘The reason I stepped away from music as a full-time thing is that the industry is so in flux that even the goal of making a comfortable, not even comfortable, like a $35,000-$45,000 a year living off of music, that was even difficult at times’ – longtime musician Matt Worobec

“It’s funny, I do have a business side to me and entrepreneurship to me but I feel like more than ever, if you want to make it in the industry, you have to have that entrepreneur bug, you have to be able to split your brain, even in the same day, to do creative tasks, like writing and songwriting, and you also need to follow up with emails and have a social media strategy.”

For Alexa Dirks, who performs under the name Begonia and was previously part of Juno-winning group Chic Gamine, there is some optimism to be found among all the current struggles.

“At the end of the day, in this self-releasing, streaming culture where you can make a song and upload it to Soundcloud the next day and have people listen to it, there are so many different ways to do things. So at times, that can feel restrictive, because I love rules and I love knowing the right way to do things, but when I really think about it, it’s actually pretty freeing in some ways because you can, as an artist, dream up multiple ways of creating your art,” says Dirks.

“And that’s how I want to try to look at it, because I’m still committed to this career, I still want to be a part of this career. I definitely know the struggles, I understand the struggles, I’m familiar with them, but my focus is more on, ‘OK, how can I make this work for me? What can I do? And how can I still be a part of the conversations?’”

Dirks doesn’t wish to diminish anyone’s experiences or challenges, but at the same time feels, for herself, the best route is to try and find her footing amid the constant shifting and figure out how to make it work for her.

“I want to enjoy my time in my career, so I don’t want to focus on… I get stuck on this conversation, to be honest, because I don’t want to sit here and complain about how hard it is when things are shifting around me all the time. I want to learn how things are shifting so that I can be a part of it and so that I can continue,” says Dirks.

“I mean, I’m not putting anyone down here but things are changing and things changed for every generation of the music industry, and you kind of have to get used to something and figure out how you fit and be creative with that.”

McManus agrees change is always going to be part of the music industry, as it is in life, and those who will always be the most successful are the ones who are able to adapt. It will at times be difficult, and embracing these changes may not make logistical sense for everyone, but if a sustainable, full-time career in music is the end goal, rethinking the approach to music creation and distribution to suit current trends is pretty much a non-negotiable move right now.

“In terms of it being sustainable, there’s been huge shift to artists sort of needing to be on the road more, to be in front of fans and to be making that personal connection, and to have that revenue associated with touring, and there’s no question it’s hard on people. We are certainly seeing that it’s something that is taxing folks and it’s something people really need to think about how to stay healthy and stay on top of,” says McManus.

“The music industry has always been to some degree as much calling as it is vocation. People that end up doing it are so dedicated to the need to, the drive to, the love of creating music and sharing it with people. And I don’t think that has changed, I think that that’s the same. The drive that’s needed to be in this industry is still there.

“I do find that a lot of young musicians coming up into being in this role of creating music in this current environment, it’s second nature for a lot of them, they understand what it means to work within a social media environment and a streaming environment. Sometimes I think for older musicians maybe it’s a tougher shift, but you know, I remember talking to the old guys in the industry about how live music used to mean a seven-day stand at a club, and they’d say, ‘How can this new touring model be sustainable?’ So evolution and changes in the industry are certainly not a new thing.”

erin.lebar@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @NireRabel

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.