No mountain too high Publishing her memoir is just the latest challenge author has overcome

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 06/12/2018 (2568 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

When Frances Mae Sinclair-Kaspick was born in Kenora, Ont., her family was told they shouldn’t keep her.

Event Preview

Book launch for The Mountain Within by Frances Mae Sinclair-Kaspick

● Friday, 7 p.m.

● McNally Robinson Booksellers, Grant Park

● Admission free

The year was 1956, and beautiful baby Frances was missing both her hands. Born with congenital amputation, her left arm ends at the elbow and her right arm ends at the wrist. Life, the doctors said, would be hard.

“The doctors advised that I should be given up into a facility because, after all, what could this baby possibly accomplish in her life?” says Sinclair-Kaspick, now 62.

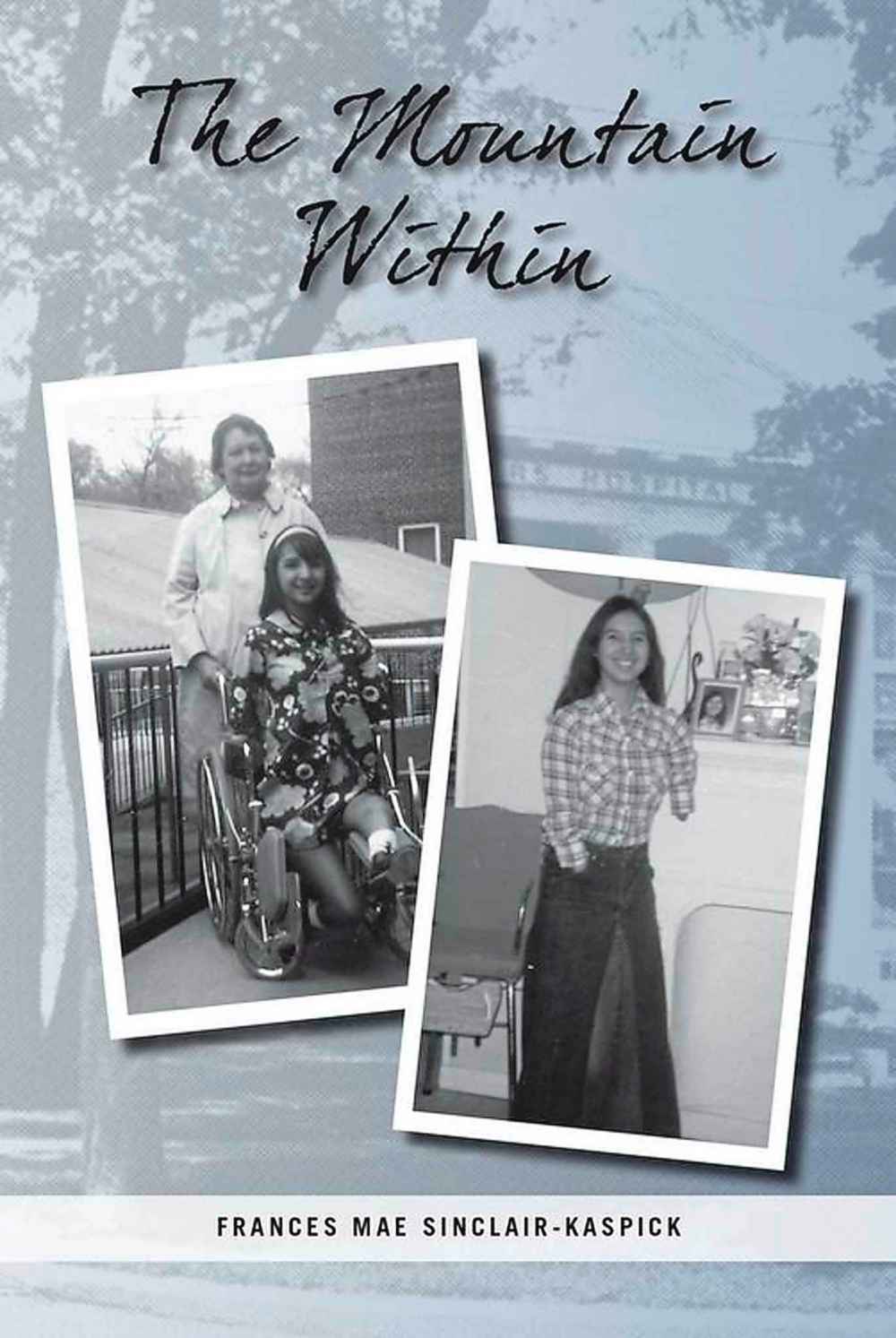

There’s a wryness to her voice when she says that; after all, she’s accomplished quite a lot. She’s fiercely determined and resilient, working hard to advocate and open doors for people living with disabilities. And tonight at McNally Robinson Booksellers Grant Park location, she’s releasing her first book, a self-published memoir called The Mountain Within. In it, she tells the story of her incredible life, as well as that of her maternal Cree grandmother, her namesake Frances, the strong, supportive, no-nonsense woman who raised her.

Because, yes, Frances Sr. kept and raised the baby. The idea of placing her granddaughter in a facility conjured horrible images of residential schools. So, she’d figure it out. If there’s a will, there’s a way.

“There were no books back then about how to raise a disabled baby,” Sinclair-Kaspick says. “She had her faith, and her strong beliefs, and she felt that this baby was brought into this family for a reason, we’re going to keep her, and we’re going to do the best we can.”

It was her grandmother’s idea to move the family to Winnipeg so that Sinclair-Kaspick could go to the Shriners Hospital, which had just opened in 1949 at 633 Wellington Cres. From the time she was six months old until she was 16, Shriners was a second home. She says both she and her grandmother received tremendous guidance from nurses and doctors.

“In those harsh days for Indigenous people, she had to learn to trust the system,” Sinclair-Kaspick says. “She was very fearful, thinking of residential school days. But the nurses were nice to her, and she saw the other disabled kids and they appeared to be fine. And I became more than what was anticipated for me. She taught me independence, how to be creative, and how to help myself without having prosthetic arms.”

To that end, Sinclair-Kaspick has retained sensitivity at the ends of her arms, so she was able to develop dexterity. She wrote The Mountain Within on a regular computer, using her arms to type.

“I can pick up a dime, I can thread a needle and sew, I can do my own makeup — even liquid eyeliner,” she says with a laugh.

By the time she was 10 or 11, Sinclair-Kaspick faced a difficult decision about whether or not to amputate her feet. They were abnormally small, and she was missing bones in her shins, making it difficult for her legs to support her as she grew.“I decided I wanted to be happy, too. I didn’t want to live in the shadows. I wanted to be in the sunlight. I wanted a deep hearty laugh. I worked hard and chose to be happy”– Sinclair-Kaspick

“I was very overwhelmed,” she recalls. But her grandmother wouldn’t make the decision for her. “She had so much wisdom,” Sinclair-Kaspick says. “She said, ‘Whatever decision you make, you’re still going to live a challenged life. But you need to be sure about your decision. I don’t want you to be angry at me if you feel you didn’t do the right thing.’”

She had the surgery when she was 14. As a teenager, she learned to walk using below-the-knee prosthetics. She also learned how to live at the intersections of being Indigenous, disabled and a girl, dealing with racism, discrimination and harassment. She recalls one particularly harrowing moment from her teenage years living on Selkirk Avenue.

“People would come into the neighbourhood, men. And they’d be on their bikes or in their cars and yell out at us, ‘Hey baby, look what I got here for you,’ and it would be rolled-up money.” Sometimes, Sinclair-Kaspick and her sisters were even followed. But it was the time they were chased by a man that led to a terrible discovery: Sinclair-Kaspick could not run on her prosthetics.

“I did not practise running with my physical therapist,” she says. “I know you see people in sports running, but not every amputee can run. My friend and sister had to grab me in their arms, and we just made it inside the door. That was absolutely terrifying. It became my biggest fear.”

Thankfully, she had a place to share those fears. Through Shriners, she met other children who were living with disabilities. “We were role models for each other, really. You’d see people doing things, like, ‘Oh, that person’s driving a car, I want to try that, too.’ We were good for one another.”

She formed powerful friendships. “Today, all these years later, I’m still friends with a lot of those people.”

Her grandmother certainly had a major hand in shaping her into the tough cookie she is today, but Sinclair-Kaspick says having friends living with similar challenges also helped her gain perspective and see the possibilities that existed for herself.

“Growing up in the disabled world, which is my world, I was lucky to see out different windows,” she says. “Whereas my sisters and brothers, they were always in the same environment. They didn’t have the opportunity to see out different windows.”

She’s built a full, happy life, which thanks to her book, she’s been reflecting on a lot as of late. Sinclair-Kaspick says she’s been working on The Mountain Within on and off for about 15 years. “And this is just volume one,” she says with a laugh. “There’s too much to say.”

She hopes her story will help others find their own inner strength.

“My grandmother always said, ‘We have no one to help us, so you have to help yourself.’ I started living like that. I knew I had to do my best to move ahead. And I decided I wanted to be happy, too. I didn’t want to live in the shadows. I wanted to be in the sunlight. I wanted a deep hearty laugh. I worked hard and chose to be happy.

“With my story, I feel I can inspire many people, not just disabled people.”

jen.zoratti@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @JenZoratti

Jen Zoratti is a Winnipeg Free Press columnist and author of the newsletter, NEXT, a weekly look towards a post-pandemic future.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.