To share or not to share Some parents reserve social media handles for their children -- others are wary about a young digital footprint

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 11/09/2018 (2649 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Last week, Facebook and Instagram were awash with first-day-of-school photographs, mostly featuring rosy-cheeked kids in adorably oversized backpacks, clutching chalkboards listing what grade they were going into, and what they want to be when they grew up.

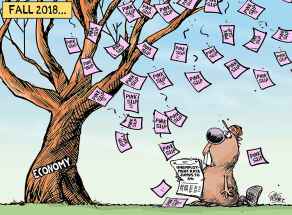

Back-to-school season is just a microcosm of what happens online everyday; you can’t scroll through social media without seeing photos of people’s babies and kids. Which stands to reason: if the point of social media is to share your life, and your kids are part of your life, then why wouldn’t you share photos and anecdotes about your kids? Just about everyone has a camera-enabled phone in their pocket, and we’re taking more photos than we’ll ever look at. Every moment is documented and can be turned into shareable content — which can be monetized if you’re a social-media influencer.

But while some parents are reserving Instagram handles for their unborn babies the moment they’ve agreed on a name, others are more wary about establishing a digital footprint for a person who hasn’t even taken their first step, expressing concerns about privacy, consent and what happens if, say, a photo of your child becomes a meme. That’s the reality of parenting in 2018: figuring out where you land on the issue of posting photos of your kid online.

“Some people feel they have no problem with it and some people, like me, don’t do it on purpose,” says Susie Erjavec Parker, a Winnipeg-based social media expert. “It’s one of those parenting issues that can be quite divisive. The main issue, in 2018, as we reach more awareness and consciousness about consent and privacy, it is incumbent on parents to think about the future repercussions of what they post online.”

Social media was on the minds of Shaun Gibson and his wife Whitney before their son, who is now 20 months old, was even born. (Speaking of privacy, not all parents interviewed for this story would share the names of their children.)

“My wife and I had a conversation about not wanting to create a digital footprint whatsoever — and then he was just too awesome,” he says with a laugh.

Gibson, who is originally from Winnipeg and is now based in Toronto, also had the nature of his job to consider. He is one of the managers for the National, a U.S. indie-rock group. “Because of their celebrity and because it’s publicly known I’m one of their managers, I get dozens of friend requests per week, sometimes per day. They’re looking for a behind-the-curtain glimpse into my client’s life, not mine. Because of that, I’ve chosen to keep all my profiles private.”

He mostly limits access to family and friends, and he is intentional about what he posts.

“We try to keep it humourous,” he says. “Nothing too personal, just lighthearted moments. Like, this is the digital version of our home VHS tapes. Because we have private profiles, we feel like we’re just sharing those videotapes to 1,500 of our closest friends. I’m sure my parents would have done the same thing if they could have gotten that many people through their front door.”

That’s not to say he doesn’t have concerns about his son being on social media. “The biggest thing we’d worry about is him becoming a target of advertising, or his data is being accessed by third parties, less about ‘here’s a photo of him and his family,’” Gibson says.

Like Gibson, Meg McGimpsey wasn’t sure how comfortable she was with her daughter having a social media presence. “As she’s gotten older, I’ve gotten more comfortable,” she says.

“Like most parents, I want my child to feel loved and respected, and I want her to feel supported by her parents as she figures out who she’s going to be. And I think she has the same right to privacy, dignity and respect that we’d afford to any adult. I want her to have a sense of control and autonomy over her life. She’s three, so that’s within limits right now. But as she gets older, and as her independence grows, I want her to feel that we’re supporting that.”

McGimpsey has developed her own social media litmus test for photos. “If it were a friend or a relative and I felt I needed their permission before posting it, I won’t post it of my daughter. She can’t give me that consent. Even though I have very cute pictures of her in the bathtub, let’s say, and they’re fairly modest, I’d never share that on social media because I wouldn’t share it of my best friend.”

That said, McGimpsey says she’s not didactic about social media and kids. “I’ll add that I love seeing friends’ and family’s kids,” she says. “Especially seeing families of friends you don’t get to see too often, and seeing them happy and healthy and seeming to enjoy each other, what a wonderful thing.”

“My wife and I had a conversation about not wanting to create a digital footprint whatsoever– and then he was just too awesome.” – Shaun Gibson

Of course, not everyone is delighted by photos of kids and babies. Some social media users bristle about the rise of ‘sharenting’ — a portmanteau of “sharing” and “parenting” — online. For a while, there was even a blog called STFU, Parents dedicated to documenting the most egregious examples of parental overshare.

Parents are far from the only ones who are guilty of oversharing on social media. We’ve hit a point Erjavec Parker calls ‘oversharing saturation.’

“Oversharing has become fashionable,” she says. “I think there comes a time in everyone’s lives where they think, ‘Oh, maybe I shouldn’t have posted this on social media,’ or ‘maybe I should have just kept that for my family.’ I ask myself, ‘What are the future repercussions of these images being out there? And what is the purpose?”

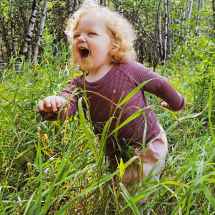

For Emily Parker, Instagram has been a way to support local businesses, many of them run by moms. She and her daughter Holly have a public Instagram page, @babyhollymae, that has 1,450 followers. Holly is a cherub with a shock of ginger curls. At 2, she is also a tiny influencer, modelling clothes and other goods made by local and Canadian makers. Her photos get a lot of heart-eyes emoji.

“I guess I started off like everybody else with private profiles, but we got into supporting small shops — a lot of them local and Canadian. So she’s actually been a brand rep for a lot of them. When you start doing that, you have no choice but to have an open profile.”

Still, despite Holly’s visibility, Parker has privacy rules for what she does and does not post. “If you’re going to post, pretend the world can see it. Is it OK with you? Is it safe?

“There are sketchbags out there everywhere — but they’re out there when you walk down the street.”

Like Parker, Elizabeth Spence didn’t want to live in fear about posting photos of her kids online.

Her Instagram account, @wellettas, now has 126,000 followers. It blew up when her squee-inducing #NappingWithNora series featuring her youngest son, Archie, snuggled in with her rescue English Pointer Nora, went viral. (Spence is married to Free Press director of photography Mike Aporius.)

“At that point it was like, ‘OK, people are looking at this now,’” she recalls. “There was a brief point where I turned it private because I felt uncomfortable with people I didn’t know looking at the kids — we all know there are pedophiles and people with skewed views about kids out there, and that scared me.”

Ultimately, though, she didn’t want to let the bad people win. “I have a set of rules in my head. I don’t do anything that would embarrass the kids — like, if their school friends saw it, would they feel uncomfortable? Especially with the older kids,” she says, referring to her nine-year-old son, Wellington, and her six-year-old daughter Loretta. “They have veto power. They have control over their image.” (Like Parker, Spence also does some influencing, and is selective about what brands she’ll showcase.)

While the response to her heartwarming photos has been overwhelmingly positive on Instagram, it was actually the coverage by traditional media that brought out the trolls. When the photos of Archie and Nora went viral, many outlets — including BuzzFeed, The Ellen DeGeneres Show, Good Morning America, and The Daily Mail — picked up the story. Commenters, particularly those at The Daily Mail, were cruel.

“People are horrible on there,” she says. “They’ll say stuff like, ‘you should have your kids taken away from you,’ and somebody was fat-shaming Archie when he was like, nine months old. I don’t read the comments. I know people just want to say mean things sometimes.”

Spence doesn’t allow the bad to outweigh the good. Her account also documents her life with her other rescue dogs and offers some light in a sea of fake news and outrage. “I get a lot of positive feedback,” she says. “(My Instagram feed) expresses love and kindness, and that’s a thing people want to see in this day and age.”

When it comes to navigating social media as a parent, Erjavec Parker says leading by example and having ongoing, age-appropriate conversations is important.

“What do you want your children to see you getting pleasure and validation from?” she asks. “If your children see you posting things and furiously checking your Instagram for likes and comments, what does it say to them about what’s valuable in life? We’re raising a generation who is already suffering from anxiety and depression from comparison online, and ‘likes’ and worth. We need to be careful about what we’re teaching our children about what’s real and valuable.”

That’s something Spence already discusses with her older children. “We’re always conscious of reminding them that things aren’t real, and that a lot of people are trying to sell stuff,” she says. “There’s different sides of social media. There’s the fun aspect of social media, but also navigating that not everything is truthful.”

Gibson’s son is still a baby, but as he grows, he will have a say about his image being posted online.

“The moment he wants something to come down, or doesn’t want something to be up at all, that’s fine,” he says. “As he develops, we’re going to continue to be proud of him and maintain our family narrative to our friends and family in a way that we’re comfortable with — but as a member of that family, he will have a voice.”

McGimpsey is taking a long view, and thinking about who her daughter might be a decade from now. Because that’s the thing about eventually stepping into a digital footprint that’s already been established for you: sometimes, the shoe doesn’t fit.

“I want it to be flexible enough that she gets to rewrite some of that, she gets to decide who she is,” McGimpsey says. “Our view of her might not fit with her view of her.”

jen.zoratti@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @JenZoratti

Jen Zoratti is a Winnipeg Free Press columnist and author of the newsletter, NEXT, a weekly look towards a post-pandemic future.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Wednesday, September 12, 2018 10:40 AM CDT: fixes typo