Prescription programming TV friends help fight the fear For nearly 40 years, a low-budget hour-long closed-circuit TV show has been one thing sick, frightened patients at Children's Hospital can count on

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 24/08/2018 (2664 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The hardest-working star in Canadian television history has been on the air for almost 9,000 episodes.

The studio lights buzz above him, illuminating the dust in the air and causing his wide eyes to glimmer invitingly like an old friend who can’t wait to ask how you’re doing.

His pre-show routine is the same each day: once the previous episode is complete, he rests until the next one begins 23 hours later, perched with his neck — if you could call it that — hooked over the back of a black office chair next to the tower of VCRs, computer monitors and a tiny television screen mounted atop a mountain of drawers labelled “pipecleaners,” “pom poms” and “eyes.”

Just before 1 p.m. each weekday afternoon, the star — with the silky, blue velour skin, the gaping red corduroy mouth and black shirt-button eyes — awakens from his beauty rest, and a child-life specialist named Maria Soroka slips him onto her right hand like a glove as the red light atop the TV camera turns on.

It’s showtime.

In a few moments, the star, who was born in the early 1980s but maintains a perpetual state of childlike wonder, will have his visage beamed outward to a captive audience of no more than 150. His name is Noname, his studio is on the second floor of the Winnipeg Children’s Hospital, and unless you or your loved ones have ever had to stay there, odds are you’ve never heard of him before now.

Noname is, of course, a mere hand puppet, but on these wards — where hundreds of young patients and their parents endure devastating pain and anguish — he’s a full-fledged celebrity.

Children still send him fan mail in an era where postcards have been replaced by Instagram stories. Often, they request he leave the friendly confines of his studio to visit their rooms. Over his nearly 40 years in the health-care profession, he’s been close by when called upon for emergency procedures. Before major surgeries, children pat his head, and he tells them to be brave, that they’re strong and that they can do it. And no matter what happens, he’ll be back on their television screens each afternoon at 1 p.m., sharp. In the business of live television, taking a day off isn’t an option.

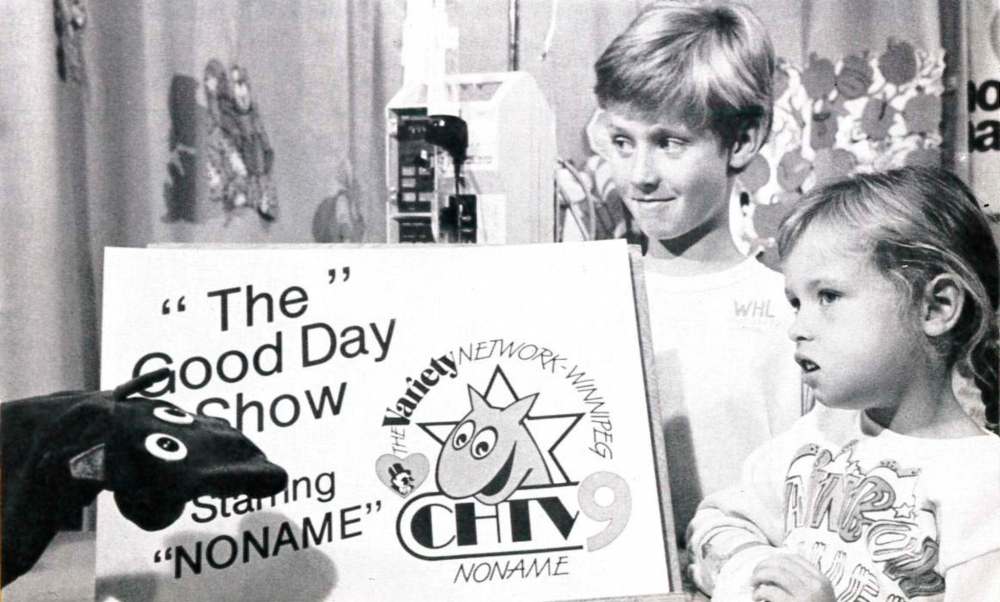

The Good Day Show, produced by a rotating team of dedicated child-life specialists and volunteers for CHTV — Children’s Hospital’s closed-circuit television network — is an hour of essential medicine.

A hospital is a fragile environment where nothing is entirely predictable. It’s structured, no doubt, but things can, and do, change without notice. As quickly as a patient is on the mend, an infection strikes, a surgery goes wrong or a blood test comes back with results less promising than the doctors had hoped.

It’s a terrifying place for parents to be. Imagine what it feels like for a five-year-old child.

In a hospital, there is little room for choice. Some children who want nothing more than to go for a walk in the park, can’t for months on end. Many procedures are painful, but they’re necessary; there’s a reason they’re called doctor’s orders and not doctor’s suggestions.

Child-life specialists make it their duty to reduce anxiety and stress related to the difficult surroundings in which they work. They encourage the young patients to understand what they’re going through and deal with it in a healthy, meaningful way: to treat the whole child.

For a child in such a rigidly controlled world, the simple idea of holding a remote control, pressing the power button and seeing a blue-and-red puppet bopping back and forth is a radical act. A question every viewer asks whenever they sit in front of a television set is, “What do I want to watch?” At the Children’s Hospital, the question became the answer.

•••

In the late 1970s, Debbie Guttentag graduated from the University of Denver with a doctorate in developmental psychology. Her husband, also fresh out of school, had been offered a job at the University of Winnipeg, so the pair packed up and moved here, a city neither knew much about. Guttentag and her husband bought a house and began settling in. She was 30, had come from Montclair, N.J., with the accent to prove it, and needed a job.

In the house next to the Guttentags’ lived Dr. William Albritton, the head of pediatrics and infectious diseases at the Children’s Hospital. Albritton was giddy to discover his new neighbour was a highly trained psychologist without much to do in a new city, so he approached her with a proposition.

“I have this problem at the hospital that’s been bugging me,” he told Guttentag. “Would you help me out with it?”

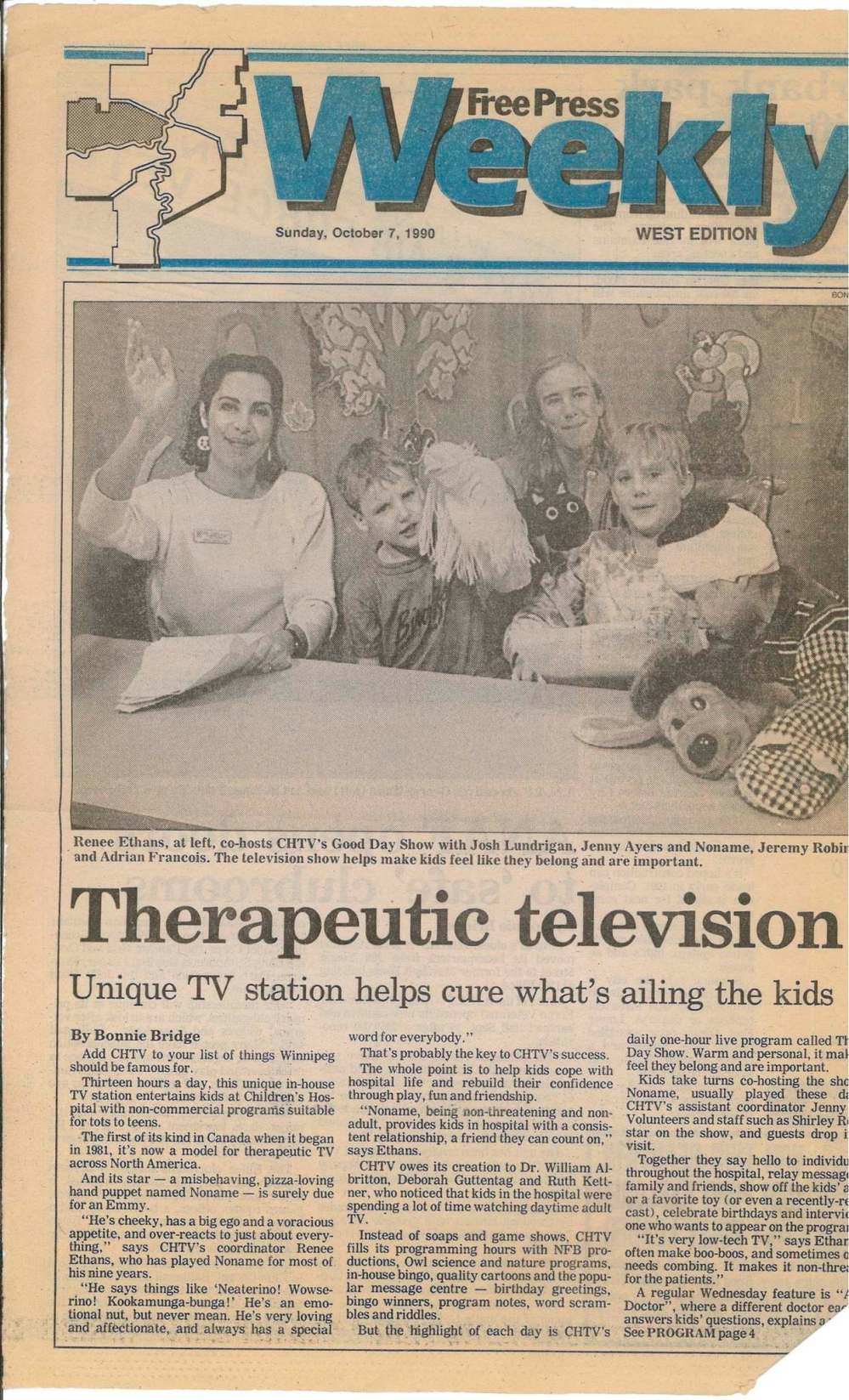

The issue that had been vexing Albritton didn’t have to do with a scanner, a testing facility or a ventilator, but an altogether more common piece of hospital electronics: the television. In those days, before the explosion of cable and satellite, when streaming services such as Netflix or YouTube were science-fiction pipe dreams, children’s programming was difficult to find.

Sure, there was PBS, with Sesame Street and The Electric Company, but in the afternoon, television was a wasteland devoid of seven-foot-tall birds or grumpy trash-can residents. In each room in the hospital, now nearly extinct tube-TV sets were watched endlessly by patients looking to fill their days. What concerned Albritton and Ruth Kettner, the director of the child-life department at the time, was that the content was doing more harm than good.

At most hours, it was more likely a kid was watching Days of Our Lives than Charlie Brown. One patient, a burn victim, had been traumatized by a character lit aflame on a soap opera. Something had to be done. Guttentag was excited about the challenge, but was intimidated by the prospect of studying what were then hot-button ideas: the effects of television consumption, the modernizing world of video technology.

Guttentag, Albritton and Kettner put forth a proposal to the hospital research foundation. The objective? “To offer the patients in the Winnipeg Children’s Centre alternative children’s television programming through the installation of a closed-circuit station and to evaluate the impact of alternative programming on television viewing patterns of hospitalized children.”

But before the project could start, the group needed to empirically prove patients had been watching shows more suited for their parents than for themselves.

From November 1979 until February 1980, Guttentag paced the hallways at the hospital, clipboard in hand, peeking into each room at half-hour intervals from 9 a.m., until 5 p.m., to see what was on the screen. She stuck out like a compound fracture. Doctors initially questioned Guttentag’s presence: “What are you doing here? Who are you?”

Over the course of the field research, she observed 845 patients, and the results supported Albritton’s concern. During an eight-hour workday, patients averaged nearly four hours of TV, much more than non-hospitalized children. When lunch was served, more than 60 per cent of children tuned in. But in the late afternoon, three-quarters of the television sets were on, and what was playing wasn’t made for children: six per cent of patients were watching an adult talk show, 15 per cent a cooking program and 79 per cent a soap opera.

“Overall, the data indicate that television is being used heavily within the hospital, but it is not being used well,” Guttentag wrote in her summary. “It is ironic that while pediatricians are becoming increasingly concerned about the effects of home viewing of violence and exploitative advertising, television has become an increasingly pervasive part of the pediatric hospital environment.”

With the data to support their original hypothesis, the child-life department pushed to develop its closed-circuit network with alternative programming. Children’s Hospital Television (CHTV) was born.

•••

The first broadcasts were produced in Studio CE-011, now a garbage room, in the hospital’s basement. Amid a series of storage rooms was one overflowing with junk waiting to be emptied. The staff cleared it out and built a primitive studio — a downscale, subterranean Tonight Show-style set. They hung blue curtains, rolled out a carpet, installed lights, and placed a desk in front of a bulky camera. The whole setup cost about $6,500. Now, the show shoots 250 episodes each year and has an operating cost of $140,000, including salaries, equipment and upkeep. It is funded by the Children’s Hospital Foundation. The showrunners have maintained the low-budget model works.

With the space ready, it was time to come up with programming. VHS tapes were purchased for $45 per hour of content, subsidized by a community group in Minneapolis, where the children’s hospital there had started its own studio not much earlier.

A man there named Larry Johnson plucked a security camera off the wall, mounted it in the studio, and began producing the first live television show in known pediatric hospital history. If Minneapolis could do it, why couldn’t Winnipeg?

“CHTV and the child-life department instilled in me that I was going to be OK” – former patient Crystal Rondeau, now 29

A typical day’s schedule started at 9 with a tape from the National Film Board. Lassie or Big Blue Marble or Hot Fudge came next, followed by Lambchop and the Professor or Free To Be You And Me. But the piece de resistance — an hour-long variety show put on by the child-life staff — aired at 1 p.m.

The show needed a title; the English translation of Guttentag’s German surname is “good day.” That was easy.

She knew the show needed a puppet to serve as the live host’s foil. A volunteer who sewed bibs and knick-knacks for sale in the hospital gift shop was approached, and a few days later she proudly presented Guttentag and Kettner with a blue-and-red critter. It was Noname, and it was perfect.

Noname rocketed to hospital-wide fame, and the network became a hit. Children who were able left their rooms to sit on set during the show’s production, and they’d send down drawings and gifts for Noname and his co-host. The number to call in to the show was flashing at the bottom of the screen, and the lines were often backed up with patients waiting to say hello on the air. Every show started with Noname saying hello, by name, to every child in the hospital.

“It was weird for a 12-year-old to be comforted by a puppet,” says Leanne Nickel-Gorchynski, who spent two months at Children’s in 1985 following an all-terrain vehicle mishap. “But in the hospital, things change.”

A survey showed 98 per cent of staff who responded to Guttentag’s second survey said CHTV had a positive impact on patients, and an overwhelming percentage felt it positively impacted staff. When money ran out, the pediatricians funded it themselves for a year. When asked to name their favourite part of the hospital, about half of the patients chose CHTV. No other response came close. Just about every room Guttentag looked into had the Good Day Show on at 1 p.m., or at 4 p.m., when it was repeated.

But as much as the data supported the idea television could be a healing balm, it was the anecdotal evidence that gave the Good Day Show staying power. There was Carl, the quadriplegic two-year-old who went on a hunger strike until Noname reminded him to eat with a song during every broadcast and by sharing a meal with a co-host. There was bedridden Bobby, who spent hours with his arms draped over the television cackling at Noname. And Jenny, a little girl with cystic fibrosis who was too weak to visit the studio for her fifth birthday party; everyone in the studio sang Happy Birthday as Jenny watched from her bed. When she died, her parents asked that donations be directed to CHTV.

In 1982, Guttentag left the hospital, and Renée Ethans joined the staff as CHTV’s assistant co-ordinator. As soon as she slipped Noname onto her right hand, she was hooked. The show blossomed under Ethans’ guidance, and segments such as Bingo, Ask the Doctor and Tic-Tac-Toe became viewer favourites.

The show and network became Ethans’ life, and Noname became an inextricable part of her personality. She took the puppet on family vacations and on tours of other children’s hospitals around the country. At the wedding of Maria Soroka, who has helped operate CHTV for almost 25 years, Ethans MCed with Noname on her hand.

Ethans served as the network’s co-ordinator for 28 years, until 2001, when she became the manager of child life, a position she held until her retirement in 2017. In her kitchen on a recent August afternoon, Ethans brought her original Noname puppet out and immediately her voice went up three or four octaves. With the puppet on her hand, she recounted dozens of stories showing CHTV’s power: children who wouldn’t talk unless it was with Noname, or who wouldn’t leave their rooms unless it was to be a guest on the show.

She welled up when speaking about Brenda-Lea Tully.

The strawberry-blond girl was first admitted to the hospital in 1977, when she was a year old. At first, her mother Irene Tully didn’t suspect anything out of the ordinary was happening to her daughter, who was born at six pounds, eight ounces, and 20 inches long. But then she started missing milestones. She couldn’t sit up or roll over, never walked or crawled. A doctor told Tully that Brenda-Lea was a lazy baby, and that all would change in the coming months. But subsequent testing would prove otherwise: Brenda-Lea had Type 2 spinal muscular atrophy. She’d never walk, and the Tullys had to prepare for a lifetime of hospital stays.

“We had to grieve the loss of what we thought (her life would be like),” says Irene.

When Brenda-Lea turned five, in 1981, she began having severe and frequent bouts with pneumonia and the hospital visits became more frequent. She was rarely alone, but still found the hospital too quiet and too removed from the excitement of the outside world. Luckily, CHTV launched during that time, and she found solace in the glow of the TV screen. When Noname said hello, for a moment it seemed like she wasn’t in the hospital; the show made her that happy. Whenever she was able, she went down to the basement studio to be on-air or watch the show from behind the scenes.

“As CHTV got going, our daughter actually looked forward to being in the hospital,” Irene says.

The Good Day Show was the only constant during Brenda-Lea’s time in the hospital. From infancy until adulthood, she was there every few weeks, even when she was 18 and preparing to move to the adult side of the Health Science Centre complex. She graduated high school and went on to the University of Winnipeg to earn an honour’s degree in psychology with a minor in sociology. In 2004, she started her dream job: helping people with disabilities with computer programming. Before long, however, she began experiencing severe pancreatitis attacks and lost mobility in her right hand, as well as her ability to speak. Rather than quitting, she learned to use a computer by sipping on a straw and puffing Morse Code. In 2008, she died at the age of 32.

In the 1980s, when Brenda-Lea was still in Children’s, a community association in her hometown of Marquette had leftover money it didn’t know how to spend. The group asked the Tullys whether it could be donated to help Brenda-Lea or to research. Irene Tully declined, suggesting the money go to CHTV instead. The organization, which holds annual socials, has raised close to $50,000 for the Children’s Hospital Foundation.

“I’ll never forget what Irene said to me,” Ethans says. “Some children can’t wait for research.”

•••

Crystal Rondeau was admitted to the hospital more than 300 times from the age of three until she was 18. Her medical file contains 37 volumes. Like Brenda-Lea, Rondeau has SMA II, and her fourth birthday present was a medical dictionary. As she read through the massive tome, the television was always on CHTV, and she’d call in to say hello to Noname after he said hello to her.

In the mid-’90s, Rondeau made friends on her ward and, with a girl named Stacy, made an analog clock for Noname that looked like pizza, the puppet’s declared favourite food. The show helped solidify an everlasting bond between the girls, who might not have met were it not for their illnesses. But as always, in the hospital, things changed in an instant, and nothing seemed constant except for the Good Day Show.

“CHTV was all she could think about,” says Crystal’s mother, Cheryl.

When Crystal was 13, she was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and then a month later, Stacy died. While her mom attended Stacy’s funeral, Rondeau held her own service with the help of a child-life specialist in the hospital’s chapel.

While mourning, she still had to go through treatment, and at the time, doctors thought the chemotherapy would send her spiralling into respiratory failure. Rondeau gave the go-ahead, and she made it through the chemo with child-life specialists there to guide her through it. But at 18, Crystal had to leave Children’s, and she fought tooth and nail to stay.

“CHTV and the child-life department instilled in me that I was going to be OK,” she says.

Now 29, she is nearing the end of her life and is on a ventilator at her home in St. Andrews. At the moment, her hair is sleek and brown, but it’s often dyed in electric hues. Her body is covered in tattoos, many of which act as daily reminders of friends who’ve died. “Twenty-seven friends,” she says.

There’s a fluttering butterfly on one of her biceps in honour of Stacy. The room is painted a deep purple, and across her bed are stuffed animals and colourful blankets. It’s the ventilator that keeps her breathing, but Crystal has discovered she’s living with a purpose bigger than herself.

“Giving children the chance to be on television, or to be involved in it, is like handing them a megaphone. That’s tremendously powerful to kids who may not have any choice in their hospital experience” – Cleve Sauer, child life television co-ordinator at Halifax’s IWK Health Centre

She doesn’t approach it with sadness or negativity, but instead uses her time to advocate for disability rights and to educate the public about her condition. She’s starting to write an autobiography and communicates constantly with parents and children who have questions about her condition. She makes the effort to visit schools and other places to speak despite the pain and exhaustion that results from using her wheelchair. Her blog, Crystal Lee: My Uncensored Life, provides a peek into her highs and lows, sometimes through video. “I’m still alive lol,” Rondeau posted July 10. “I’m hoping to start working on videos next week.”

It isn’t television, but her posts function as an extension of CHTV’s mandate: to demystify illness, to remind people they have value and that their condition doesn’t define who they are and what they can be. Along with videos of syringes, IV ports and catheters, she posted one from beside the stage at a Papa Roach concert.

“A video can change the way people think,” she says.

•••

Other children’s hospitals across Canada have adopted Winnipeg’s model of live programming. Halifax’s IWK Health Centre has been doing pre-taped programming for seven years, but is transitioning to live shows over the next few years.

Cleve Sauer, IWK’s child life television co-ordinator, says Winnipeg’s hospital has provided a roadmap for successful programming.

In the U.S., many children’s hospitals have received multimillion-dollar donations from celebrities such as Ryan Seacrest to build in-hospital studios, but, Sauer says, a small budget is all that’s needed to make a difference.

“Giving children the chance to be on television, or to be involved in it, is like handing them a megaphone,” Sauer says. “That’s tremendously powerful to kids who may not have any choice in their hospital experience.”

The medium, it turns out, is a medicine.

•••

Maria Soroka slips Noname onto her right hand and turns on the camera with her left, focusing the lens on child-life specialist Nicole Hase-Wilson, the day’s co-host, before hopping onto a chair just off set. Soroka is out of view, but Noname bops back and forth in the bottom right corner of the screen.

Noname is in his zone, and Soroka makes it look effortless, but there are days when it isn’t so easy. Many viewers are chronically ill, and there likely has never been a TV star who’s had to say goodbye to more fans. On one occasion, when many child-life specialists attended the funeral of a longtime patient in the morning, Soroka returned just before showtime and had to get in character. For an hour, she had to make people smile.

“Then, I just went out in the hallway and cried,” she says.

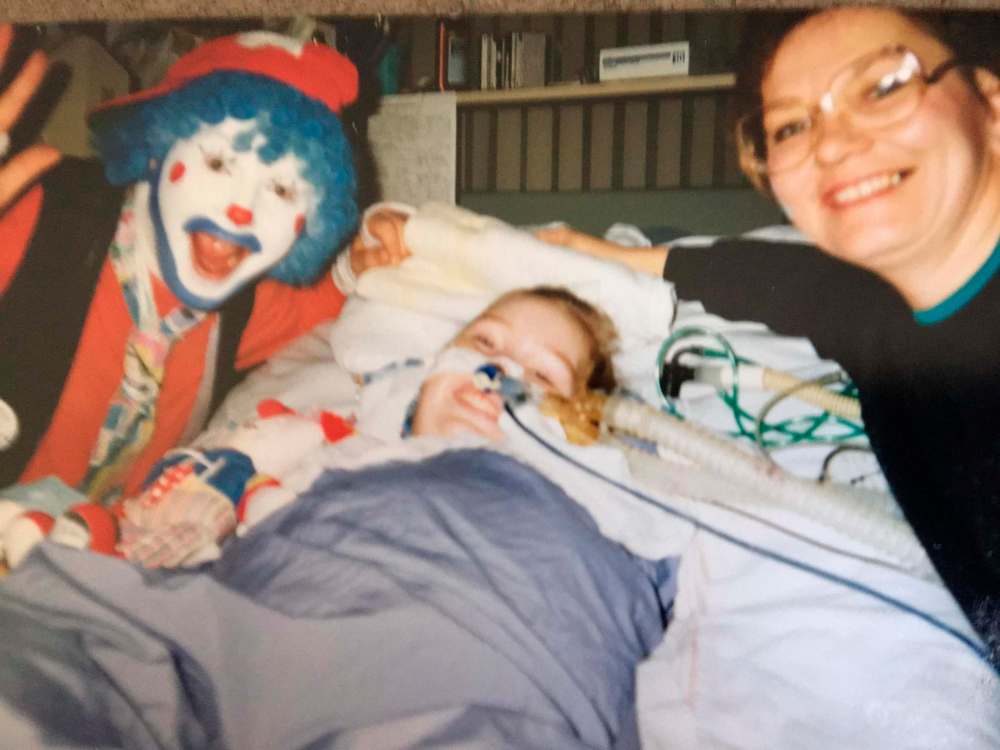

Soroka’s voice goes up, and her eyes widen as Noname cracks jokes. When he nods, she nods. Over the hour, Noname says hello to every patient by name, does crafts and at 1:30, Onri the Clown bursts in to do magic tricks and gags with the hosts. Noname has seen them hundreds of times, but he giggles whenever Onri makes a funny face or sound effect. The rapport is effortless.

The lights in the studio flicker, and Hase-Wilson says, “It’s live television, folks.”

Soon, the show is almost over, but it’ll be on again at 4 p.m. No children were in the studio for this show, and none called in either, but Soroka knows the TVs in many patients’ rooms are on. “We will see you tomorrow,” Hase-Wilson says directly into the camera before the next program begins.

At the Children’s Hospital, the show always goes on. The young patients can count on that.

ben.waldman@freepress.mb.ca

Ben Waldman covers a little bit of everything for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Friday, August 24, 2018 7:14 PM CDT: Typo fixed.

Updated on Tuesday, August 28, 2018 12:01 PM CDT: fixes typo