Lasting Impressions The Winnipeg Art Gallery has high expectations for its summer exhibition featuring some of the 'greatest hits' of the originally maligned and misunderstood Impressionist movement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 15/06/2018 (2737 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

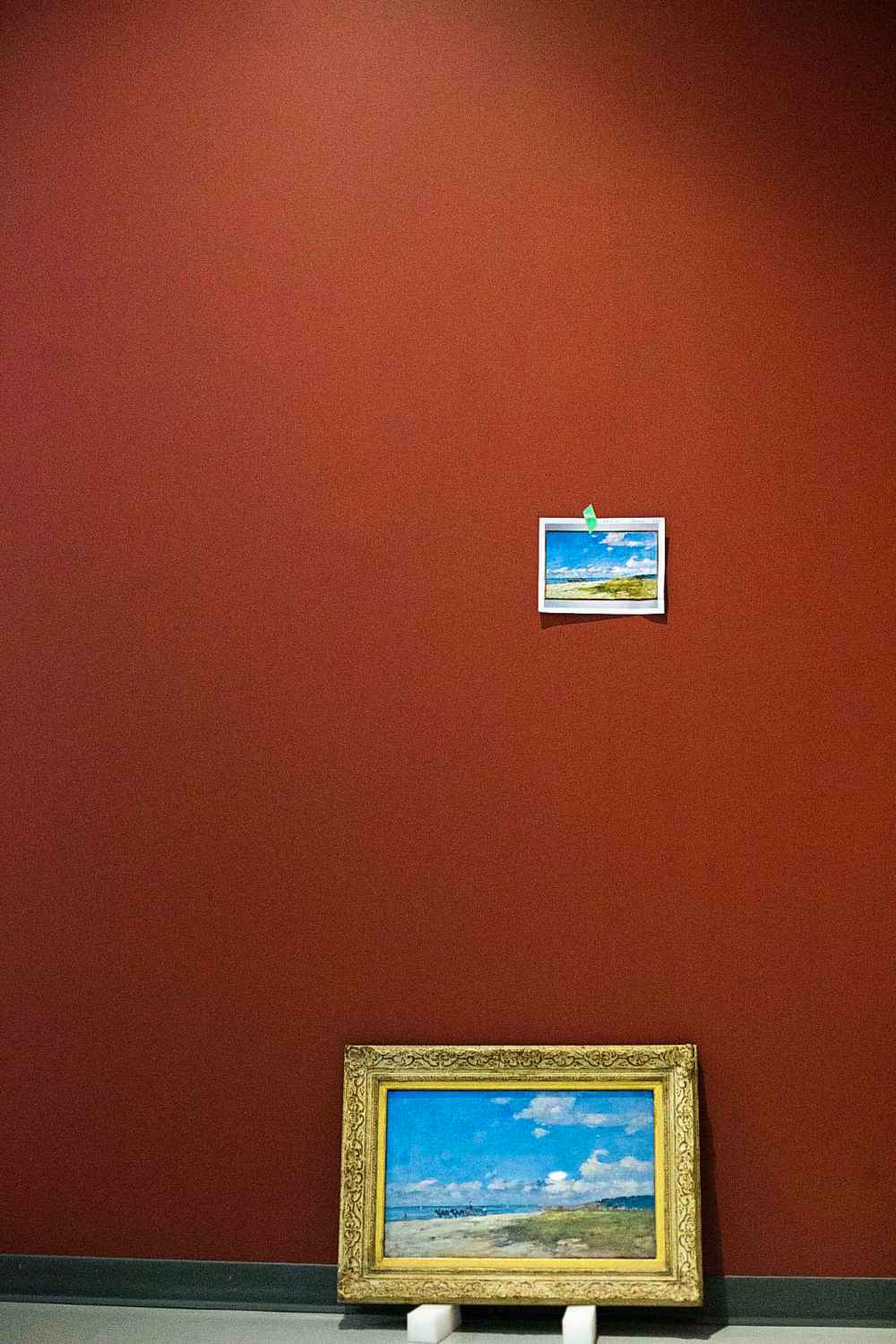

It’s hanging day at the Winnipeg Art Gallery, and just before noon the gallery’s inner sanctum is alive with calm, focused motion.

Paintings rest against the wall, soon to be raised; sculptures await their protective glass cases.

The new exhibition will open in a matter of days and there is still so much left to do.

For months, Stephen Borys has been preparing for this transformation. Now, the WAG’s executive director is animated and restless, a kid on Christmas morning. He paces the gallery, soaking in the wonders at his feet.

He spies a painting leaned up against one wall. It’s a picture of a single wave rolling over itself, spread under a impenetrable grey sky. Borys’s eyes light up, and suddenly he’s breezing across the room, reeled onward by some invisible line.

“Can I just show you?” he asks. “Just, for a minute?”

Now, it’s time to show the public, too. Saturday, the WAG will open the doors to what it hopes will be its next blockbuster exhibition, Summer with the Impressionists, a three-month display of iconic French artwork.

The event comprises two main shows. The star is French Moderns: Monet to Matisse, 1850-1950, a tour of 60 pieces from the Brooklyn Museum’s vaunted collection, filled out by 10 works from the WAG’s own vaults.

In Winnipeg, that exhibition is joined by The Impressionists on Paper, a companion show curated by Borys. It’s an “intimate show,” he says, featuring about 20 works borrowed from the National Gallery of Canada.

The event does not only feature Impressionist artists; its scope covers a range of art that both preceded and succeeded them. But they are the heart of the collection, both physically — in the gallery layout — and spiritually.

All the movement’s big names are here. Artists whose work sells at auction for millions. Artists whose works are sought by billionaires and museums. Artists whose names rose up to stick in the broader public consciousness.

What you’ll see

The Winnipeg Art Gallery is hosting for the first time an entire collection of French Impressionist artwork — from ‘some of the greatest hits’ to other lesser known pieces.

Here are a few of the works on display by big-name Impressionists.

The Winnipeg Art Gallery is hosting for the first time an entire collection of French Impressionist artwork — from ‘some of the greatest hits’ to other lesser known pieces.

Here are a few of the works on display by big-name Impressionists.

There are two pieces by Pierre Renoir, and a striking oceanside scene by Claude Monet. There are several sculptures by Auguste Rodin, and a breathtaking canvas by Edgar Degas, a large piece of a woman bathing.

“They have some of the greatest hits,” says Serena Keshavjee, an art history professor at the University of Winnipeg. “They have some that are lesser known, but are really interesting. They’ve given us good stuff.”

For Winnipeg, it is a rare exhibition. Impressionist works have appeared here over the years — here and there a Renoir, or a Monet — but as far as WAG staff can tell, this is the first time the city has hosted an entire collection.

So it’s no wonder, then, that hanging day finds Borys so energized as he surveys the waiting paintings.

This is not the first time Borys has seen these pieces in person; he’s visited them at their home base in Brooklyn. But it is the first time he has seen them here, in the city where he grew up, and the gallery he now guides.

Borys was at a conference in Saskatchewan the previous day when WAG staff carefully conveyed each piece from its protective crate. One by one, they rested the paintings against walls, secured by soft foam footings.

That night, after his flight landed back home, Borys slipped into the gallery hours after the WAG closed. He wandered through the dimly lit spaces, heart racing, illuminating each rare painting by the light of his phone.

With the exhibition’s opening looming, he wondered if Winnipeggers would thrill to see them the same way.

“As much as we think we know what people want, we don’t know until they walk in,” he says.

To highlight the exhibition’s significance, the WAG has surrounded the event with a full slate of programming. There will be painting workshops and scavenger hunts, daytime and Friday-night tours, four themed dinners.

Even the gallery itself has changed. Staff constructed elegant wainscotting, to recall the style of classic French interiors. They decorated one area as a Parisian cafe, to serve as an interactive space to paint or take pictures.

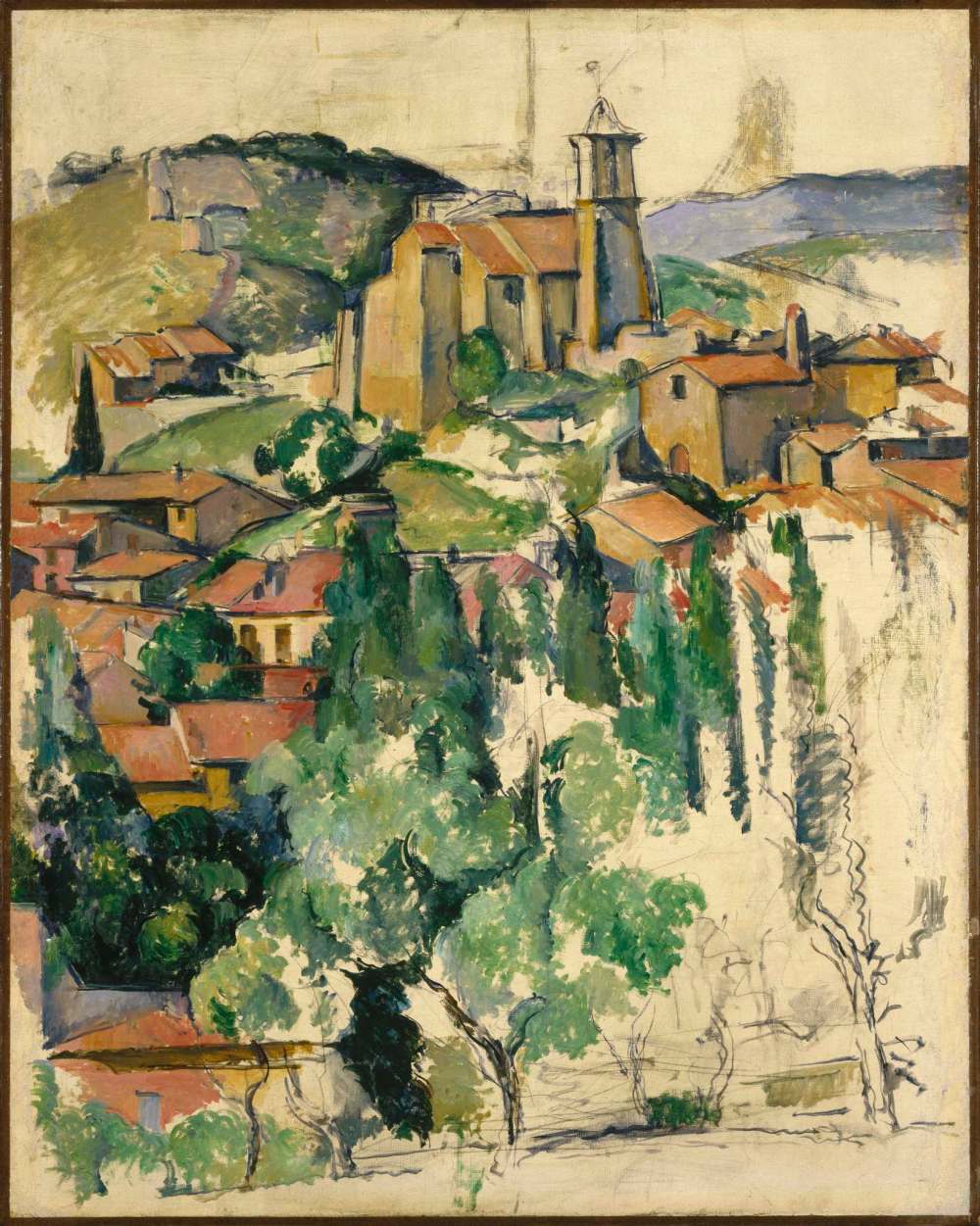

And there are, of course, the artworks. There is Borys’s favourite, an 1886 painting by Paul Cezanne. It’s a view of Gardanne, a picturesque village in the south of France, red rooftops poking through copses of blue-green trees.

The lower-right corner of the painting is unfinished, a naked patch of washed canvas. Borys points at that unfinished part, marked by light squiggles of black paint to suggest the preliminary shapes of tree trunks.

“It’s textbook,” Borys says, with a dreamy exhale. “It kind of sums up everything you need to know about how the Impressionist movement evolved. The fact that it’s slightly unfinished exposes the artist’s thinking and process.”

That’s the legacy of the Impressionist movement: it made transparent the way artists moved and worked. But times have changed, since the heady days of late-19th century France; art has travelled so far past that time.

So why should today’s public care about — as Borys puts it — a bunch of dead French white men?

It’s an interesting question, and he nods, answering himself. Because the fact is, the public does care. The fact is, more than 150 years since the Impressionists first emerged, the public is still taken with what they created and how they saw the world.

“There’s no other period in the history of art where a group of artists continue to hold such attention,” Borys says.

Nobody remembers the people who follow the rules. Only the ones who create, or break or rebuild them.

In the gallery, Borys gazes over the rows of paintings, gently resting on the floor. Some would be worth millions at auction, and right now they are waiting to be lifted, to be featured, to be seen once more.

His eyes settle on a painting of a young girl on a bench, her prim dress suggested by ecstatic flashes of paint.

“I want to show you this Manet, just for a second,” he says. “Can I just show you?”

Then he’s off, dashing across the gallery again, mirror-shine shoes tapping a brisk rhythm on the stone floor.

•••

In the spring of 1883, after years of illness, the artist Edouard Manet’s foot succumbed to gangrene and was promptly amputated.

Alas, the surgery was not effective: just 11 days later, Manet died of rampaging infection.

The artist’s death, at age 51, sent Impressionist art circles grieving. He was close friends with the movement’s stars, though he’d never exhibited at their eight independent shows; in some ways, his work had inspired them.

Across the English-speaking world, many newspaper readers learned of his passing from American art journalist Lucy Hooper. A longtime Manet observer, she reported his death in a brusque dispatch from Paris.

“(Manet) should have died not ‘hereafter,’ but long ago,” she wrote. “Then the public would have been spared some of the most hideous monstrosities that have ever afflicted under the guise of art, this sublunary world.”

The rest of the article was no less caustic. Hooper was, by then, a well-travelled critic of the Impressionist movement; she’d once called them “maniacs,” although she conceded that Manet was “less mad” than the rest.

Now, with Manet’s grave still fresh, she heaped the scorn on again. She recalled how a friend of Manet’s once rejected a portrait the artist had painted; no wonder, Hooper sniffed, as it might have scared any small children.

Yet to her, the deceased was something of a ciper. For instance, she was struck by the fact that, despite his “peculiar theories of art,” he was a gentleman in person, and “not in the least Bohemian or unconventional.”

Above all, it seemed, Hooper was confused by one thing: Manet could paint. He was skilled; he had trained.

“That was the queerest part of it,” she wrote, in a tone so bewildered that it could almost be heard through ink. “His dreadful smears and blotches, his wooden men, and stone skies and block-tin rivers, were all done on purpose.”

Manet would, in time, go on to become known as one of the “fathers of Modernism,” a legend after his own time. But when he died, it was Hooper’s view that ran in newspapers worldwide — including the Manitoba Free Press.

So that was the first thing many Manitobans heard about the Impressionists: that they were better off dead.

Other critics might not have put it so bluntly, but this was not an uncommon view at the time. Since the first Impressionist exhibitions of the late-19th century, the French art establishment bemoaned the movement.

The biggest stumbling block, for them, was one of structure. For generations, art in France had been a rigidly curated affair, dominated by wealthy patrons, and by the institutional minds of the Academie des Beaux-Arts.

It was that learned society which pronounced what painters ought to paint (portraits, landscapes, nostalgia); how they ought to paint it (composed, carefully layered); and what pieces deserved to be shown at the public Salons.

But the Impressionists were after something different. They chafed at the conventions demanded by the Academie, its rigid rules for how to paint trees. Instead, they began to wonder how to capture what the eye saw in a moment.

The found their answer in three basic elements: shape, colour and movement.

Meanwhile, the tools of the trade were changing. For the first time, paint was sold in tubes; that freed artists from their studios, where they used to prepare pigments by hand, and sent them out into the green spaces beyond.

Now, instead of finishing their pieces by lantern light, they could paint — as the French said — en plein air.

The Impressionists, more than other artists, revelled in that new-found freedom. They set up their easels on the seaside, in their gardens; they became transfixed by natural light, the way it dapples and shifts on its subjects.

Soon, the energy of that light worked its way into their movements. Where French painters had long sought to blend their canvases to a smooth, elegant finish, the Impressionists began to see how texture itself told a story.

As they painted, the things they captured became deconstructed. The details of trees, buildings and people softened, their features now sketched out by loose strokes of colour; yet somehow, their essence remained.

Sometimes, when explaining this to her U of W students, Keshavjee settles on a familiar sort of analogy.

“You know the one guy in your class that pretends he doesn’t study, and he gets the A’s because he’s a genius?” Keshavjee says, with a wry smile. “That’s what Monet is basically doing. He’s telling us that he’s working quickly.

“It’s a very spontaneous method, and he’s just catching the fleeting and fugitive because it’s natural. It’s pouring out of him. That fractured look is the look of modern art… and that’s what (Impressionism’s critics) didn’t like.”

To the French art establishment, the Impressionists’ dashes of paint were blatantly unfinished, “a soul without a body.” They decried the textured smears of paint that rose from the canvas, the ways the brush strokes showed.

The movement’s name itself came after Monet exhibited an 1872 piece titled Impression, Sunrise. One critic lamented that all the works by Monet and his friends showed only “impressions” of scenes; the name stuck.

Yet the Impressionists had tapped into something that would change the course of art forever. By releasing themselves from strictures on subject and method, they began to touch something universal, and vibrant.

“The Impressionists reflect a lot of our notion of beauty, still,” Keshavjee says. “That broken brush stroke, that sense of catching the ephemeral, was meant to be a more authentic and honest interpretation of how we see.”

The contrast can be seen plainly in Monet’s 1882 painting Rising Tide at Pourville, now on display at the WAG. Compared to the mannered landscapes of just two decades before, the cliffside scene is turbulent, almost alive.

Under Monet’s hand, energetic streaks of white dance as spray on the waves. The paint rises from the canvas, thick and unblended; the hairs of Monet’s brush directed the pigment into ridges, its texture allowed to remain.

He painted it briskly. Each mark seems decisive, put there as much by instinct as planning. Get too close, and the cliffside disintegrates into a tangle of strokes; but seen from a short distance, it feels like the sea.

•••

It’s four weeks before the Brooklyn Museum art starts arriving, and Borys is holding court in his mezzanine-level office.

It’s a long rectangle of space, crowned by a starburst of a modernist light fixture.

Borys glances up, when I point it out. Oh yes, he says, isn’t it just incredible? The light is original to the 1971 building, designed in harmony with the space; when he took over the WAG’s top job, they found it in storage.

He has been thinking a lot recently about the role of the curator. Thinking about what it means to be an art gallery director in the 21st century, when so much about how we make and receive art is being reconfigured.

Sometimes, that thinking comes back around to this: there is something precious about art being seen.

We are now, for instance, living in the age of Google. Anyone can search the visiting pieces from the Brooklyn Museum collection if they are interested, and consider Impressionist methods from the comfort of their couch.

But, like the dazzling light fixture that presides over Borys’s desk, it’s the thing itself that moves through time, connecting past and present, linking generations. The image can be replicated; the artifact has only one life.

“In an age saturated with image, people still find incredible power in the object,” Borys says. “There’s something about them. When the only thing between you and the painting is air, and you’re thinking: ‘someone made that.’”

It’s a busy time at the WAG. In the space of just a month, the gallery closed Insurgence / Resurgence, its landmark exhibition of modern Indigenous art, and broke ground on its ambitious, long-planned $65-million Inuit Art Centre.

The success of Insurgence / Resurgence, in particular, has Borys beaming. With 29 artists, it was the WAG’s largest-ever display of contemporary Indigenous work. It was also a big investment, with 12 new commissions.

Curators hoped those works would resonate with a broad audience. They did: foot traffic was strong, galleries in Vancouver and Halifax expressed interest in hosting the show and tour slots for K-12 school groups sold out.

“I didn’t anticipate it being so strong with schools,” Borys muses. “I like the fact that a group of right-out-there, in-your-face Indigenous artists making statements is appealing to Grade 3 students and there’s really a connection.

“It was really rewarding and confirming that we’re on the right track with Indigenization of the WAG.”

Now, Borys was preparing for something completely different. To switch gears so completely — from living, thriving Indigenous avant garde artists, to those dead French guys — is an interesting contrast, a “paradigm shift,” he says.

Yet that’s part of the business of running a gallery. There are shows the WAG does because they contribute something new to the vast conversation that is art; then there are shows that help pay for those risks.

Nothing is guaranteed, though. Not even with summer blockbusters. Borys knows that better than most: sometimes, public reception to the WAG’s big shows can surprise him — both for better and for worse.

For instance, Borys points to the 2012 blockbuster 100 Masters: Only in Canada. It was an exhibition of masterworks owned by Canadian institutions, assembled by the WAG to celebrate its 100th anniversary.

The contributing galleries were generous. The National Gallery sent over its best Rembrandt; the Art Gallery of Ontario chipped in with what Borys fondly recalls as an “exquisite” Picasso. So right away, it had the big names.

Still, until the exhibition opened, Borys wasn’t entirely sure what sort of numbers it would do.

To his surprise, the show was a sleeper hit, the highest-attended exhibition in WAG history. Winnipeggers literally lined up to see it; the WAG even took the unusual step of extending its hours to accommodate more visitors.

“It had incredible resonance with the public,” he says. “They liked the names and the objects. But there was a sense of national pride that these works were in Canada.”

On the flipside, he had high hopes for 2015’s Olympus, an exhibition of Greco-Roman antiquities. The show had already been a huge success in Quebec City; yet for some reason, Winnipeggers didn’t embrace it the same way.

“I didn’t think we had to convince people to come and see these objects, but we did,” Borys says.

Still, he’s betting that Summer With The Impressionists will be more like 100 Masters, than Olympus. It’s an educated guess; Impressionist shows routinely figure among the world’s top 10 most successful art exhibitions.

Which is to say, more than 150 years since the movement’s genesis, Impressionism remains a crowd-pleaser.

For Borys, this moment is a long time coming. His specialty is 18th- and 19th-century French painting; as a National Gallery curator in the late 1990s, he crafted an Impressionist show he wanted to send to Winnipeg.

The WAG declined, though Borys does not know the circumstances.

So now a big Impressionist show has finally landed in Winnipeg, and Borys is eager to unveil it. What he was not expecting, perhaps, is how this collection of century-old French works has already pushed the local conversation.

In January, he was teaching a class at the University of Winnipeg when students posed a challenge. Among the visiting Brooklyn Museum work, they noted, there are only three women: what was Borys going to do about it?

The WAG couldn’t change the Brooklyn show. But Borys did go back to the drawing board. From that challenge arose a third show, Defying Convention, which will run alongside the two featured Impressionist exhibitions.

The gallery enlisted local filmmaker Paula Kelly to comb the WAG’s vaults, selecting works by 30 Canadian women working from 1900 to 1960. Some of the pieces had long languished in the gallery’s storage.

So to present them now alongside an Impressionist blockbuster poses a direct question. Why do some artists become legends, while other trailblazers are forgotten? Who decides what art deserves to be remembered?

“So there’s a 1920 painting in the basement, hasn’t been exhibited for years,” Borys says. “Why hasn’t it been up? A curator may say, ‘it’s not a great work,’ or ‘it’s a mediocre work,’ or perhaps it’s just not strong enough.

“But the only way we’ll be able to talk like that is if the works are on display. It’s not the curator who decides if the works are good, it’s the public.

“We can sometimes become removed from the dialogue outside and think we know what’s good, or what’s bad,” he says. “Ultimately it’s the public who decides what’s good, because they’ll come and see it and talk about it.”

In a way, there is no greater tribute to what the Impressionists accomplished than to heed that lesson.

•••

Today, strong words often append the Impressionist legend. Scandalous. Revolutionary. Rebels.

Yet, while the Impressionists broke with academic convention, they were never truly radical. Some artists held progressive opinions, but few were subversive. They were, as Hooper observed of Manet, mostly “gentlemen.”

Manet’s father was a judge. Cezanne grew up in a wealthy banking family, as did Degas. Not all of the Impressionists were similarly moneyed, but most, at least, emerged from the burgeoning middle class.

So their rebelliousness, mostly, was a matter of artistic method. And where they chafed against the restrictions imposed by elite gatekeepers and academics, they found their legitimacy in a lucrative place: the general public.

Hanging Day

With detailed precision, preparator Serge Saurette hangs pieces from Summer with Impressionists, the new exhibition at the Winnipeg Art Gallery.

With detailed precision, preparator Serge Saurette hangs pieces from Summer with Impressionists, the new exhibition at the Winnipeg Art Gallery.

One pivotal moment came in 1863. That year, the Academie rejected the majority of pieces submitted for the annual Salon exhibition. Among those rejects were works by neo-Impressionists, including Manet.

The artists protested, and they had supporters. Under pressure, the emperor Napoleon III issued a statement.

“His Majesty, wishing to let the public judge the legitimacy of these complaints, has decided that the works of art which were refused should be displayed in another part of the Palace of Industry.”

The resulting exhibition — the Salon des Refuses — drew throngs to observe the rejected works. Though many attendees went only to sneer, others were charmed by the cutting-edge subjects and technique.

By 1874, the Impressionists were presenting their own wildly popular independent exhibitions.

What the critics were missing was that life in France was changing. The ascendancy of the church was fading; science was rising in its place. Napoleon III wore the title of emperor, but industry was the new king of France.

A new Paris was emerging: lively, romantic, dancing to its own melodies. The growing middle class found more time for leisure, and in that milieu of shifting economic power, the Impressionists found no shortage of admirers.

Partly, it was their subjects. The Impressionists revelled in scenes of everyday life in this new France. Their brushes fleshed out images of bustling cafes, Parisian bridges, women and children sitting in their gardens.

“They dismantled codes and rules and hierarchies and symbolism,” Borys says. “This is really the greatest moment of secular art, where everything is levelled. And they’re painting everyday life, period.”

Where the Academie turned up its nose, the public opened its wallet. Soon, many Impressionist painters found wealthy sponsors amongst the industrialist class. They held private showings and built a network of dealers.

So in a way, though they were rebels to the 19th-century art, they were harbingers of what was coming: the rise of the general public as tastemakers and consumers. A culture shaped less by cloistered elites, than by the masses.

Still, the Impressionists were progressive in some notable ways. One was around gender; at a time when women were forbidden from training at the Academie, the Impressionists welcomed female artists into their exhibitions.

Several of those women rose to prominent positions within the movement, including Berthe Morisot, whose tender portrait of a woman and her daughter now hangs at the WAG and and Mary Cassatt, an American painter.

Cassatt’s case is instructive. An American, she moved to France to pursue her artistic career. After years of frustration with the chauvinist tenor of the Salon, she was invited to show with the Impressionsts by Degas.

It’s a remarkable inclusion, given the constraints on women in 19th-century France — they were not allowed to visit parks or cafes without a male escort — but also what came after: subsequent art movements were openly sexist.

“There was respect for the women, and certainly the critics loved their work,” Keshavjee says. “They were welcomed and reviewed and treated quite well. It’s one place where women were allowed to get a head start.”

What’s notable is that this popular engagement never really faded, even as the context around the art changed. Which takes us back to the opening question: why is the public still so enchanted with this art a century later?

Today, the loose early Impressionist forms that gave Lucy Hooper vapours seem downright tame. We live in a world that has moved through cubism, surrealism and abstraction. We live in a world drenched in graphics.

So to contemporary generations, accustomed to far more dramatic breakdowns of form than the Impressionists ever attempted, there is little about their work that challenges. So why do they still command such attention?

It’s simple, Keshavjee says. The pieces are now, as they were then, pleasant to look at. They did not require significant artistic literacy to understand; they were painted to be enjoyed, hung over dressers.

“It’s very pretty,” she says. “It’s soothing. It’s not necessarily profound, but it is very pretty.”

By the late-20th century, that intersection of accessibility and historical resonance had firmly established the Impressionists as blue-chip art. Their works continue to show well, and sell well, often for phenomenal sums.

In 1990, Renoir’s Bal du Moulin de la Galette sold for US$78.1 million, then the second-highest price ever fetched by a painting; in 2011, Qatari royals bought a Cezanne for an undisclosed sum, at least US$250 million.

That’s not because gatekeepers decided the art was important. It’s because regular people did.

“Why are they so popular? Why are they so expensive?” Borys says. “It’s because the public responded and embraced the works. It wasn’t articles written by the curator or the critic, because they were trashing the work.”

And it’s the same for the WAG now, too. This summer, it will host works by some of the world’s most celebrated artists. Maybe the public will adore them; maybe they’ll find the same beauty that enchanted 19th-century Paris.

Or, maybe they won’t. Only time will tell — and that is the most Impressionist thing of all.

“Public taste and ownership has changed everything,” Borys says. “We can do a lot inside. We can write good catalogues and do good marketing. The public’s going to decide if they want to see Monet and Mary Cassatt.”

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Friday, June 15, 2018 9:12 PM CDT: fixes typo in cutline

Updated on Saturday, June 16, 2018 12:06 AM CDT: adds video