At the first star, forever and ever Despite war and politics, refugees and Ukrainian-Canadians hold fast to tradition, marking Orthodox Christmas

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 06/01/2023 (1068 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

At the first star over the Prairie skies Friday night, Ukrainian families across Canada prepared themselves to mark Sviat Vechir, the Orthodox Christmas Eve celebrations, which begin with a Holy Supper.

The supper features 12 Lenten dishes, including cooked wheat or kutya, verenyky, also known as pierogi, a simple borscht, and kolach, a spherical braided bread that forms the centerpiece of the Christmas table.

In the weeks leading up to Sviat Vechir, Orysia Ehrmantraut, the baker-owner of Baba’s House on Bannerman Avenue, was busy fulfilling her orders for kolach.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS In her small-batch kolach production, Orysia Ehrmantraut uses 100 kilograms of flour, 20 kg of sugar, two pounds of yeast, 15 dozen eggs, 10 litres of milk and 10 1.3-kg tubs of margarine and butter.

“It is an extremely significant bread within Ukrainian culture and is an ancient symbol of hospitality from pre-Christian times,” she says. “In some families the bread is used as a form of greeting.

“Kolach has a lot of spiritual meaning to it. Before I begin the process of making it, I say a short prayer asking God to help this unworthy person make this kolach for His glory.”

Ehrmantraut’s kolach are made by hand and in small batches. She uses 100 kilograms of flour, 20 kg of sugar, two pounds of yeast, 15 dozen eggs, 10 litres of milk and 10 1.3-kg tubs of margarine and butter to make the bread, and will have baked all the way up to the day itself.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Orysia Ehrmantraut will have been baking kolach right up until Orthodox Christmas Day.

The last three loaves coming out of her oven will be for her own Christmas table.

Each bread is shaped into a circle, which represents eternity. In her family three of the braided breads — representing the Trinity — are stacked and topped with a candle.

“When the candle is lit it represents Christ as the light of the world. The candle also represents the star of Bethlehem that led the three wise men to the manger where Christ was born,” Ehrmantraut says.

Sviat Vechir is usually a time for merriment and feasting. After the Holy Supper, families troop to church for the midnight service before coming back home to eat more food.

This is usually when the kolach — made with eggs and milk and thus not strictly considered part of the Lenten feast — is consumed.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Orysia Ehrmantraut with a kolach made at her bakery, Baba’s House Ice Cream and Desserts.

But as Putin’s war rages on in Ukraine, this year’s celebrations will be muted for some.

Svitlana Poliezhaieva, who arrived in Winnipeg in August with her husband, children and mother-in-law, is part of the 15,000 Ukrainians who now call the province their home.

This will be their first Ukrainian Christmas in Canada but the 33-year-old mother of two does not feel as if she has anything to celebrate.

“It’s not really a celebration because of the war. It is not like it was before,” she says. “Our life is divided into what was before and after, and it will forever be this kind of feeling

“But I will mark Christmas because I want my kids to have this tradition. It is important for them to feel safe and experience this.”

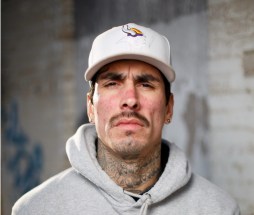

JESSICA LEE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS ‘It’s not really a celebration because of the war,’ says Svitlana Poliezhaieva, with daughters Polina, 10, and Maria, 6. ‘But I will mark Christmas because I want my kids to have this tradition.’

The family came from Kyiv, and are currently living in Transcona where the children, ages six and 10, go to school. She still has family in Ukraine.

“My mother is in Kyiv. I feel terrible about it. I try to talk to her weekly, but we have to wait until they have electricity and connection. Sometimes we have a video chat, and it feels like a luxury. So far she and my other relatives are doing good, but you will never know what will happen… where the rockets will fall.”

It’s also a complicated Christmas for Canadians of Ukrainian descent as religious politics threaten to overshadow the celebrations.

In Ukraine, many Orthodox Christian families switched their Christmas to Dec. 25 to align themselves with Europe. For them the Jan. 7 celebrations indicate an allegiance to Russia.

The move away from the Julian-calendar Christmas date of Jan. 7 has been underway since 2017 when Ukraine made Dec. 25 a national holiday. It gained traction after Russia’s invasion, and in October this year the Orthodox Church of Ukraine allowed dioceses to hold Christmas according to the Gregorian calendar (Dec. 25).

MIKE DEAL / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS ‘Ukrainians are resilient,’ says Father Gene Maximiuk at the Holy Trinity Ukrainian Orthodox Metropolitan Cathedral. ‘That message of hope has to always be the message that prevails, in this situation and in many situations.’

Religious tensions have been brewing for some time, says Father Gene Maximiuk. The parish priest of Holy Trinity Ukrainian Orthodox Metropolitan Cathedral on Main Street is referring to the 2018 Moscow-Constantinople schism when Russia severed ties with the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople after the Holy Synod granted the Orthodox Church of Ukraine tomos of autocephaly (self-governance).

Tensions intensified after a series of raids on Moscow-affiliated Orthodox churches and monasteries uncovered stockpiles of pro-Russian propaganda with dozens of priests arrested for allegedly collaborating with Russian forces.

The discovery led to the Ukrainian government’s crackdown on all Moscow-affiliated Orthodox churches with President Volodomyr Zelenskyy stating his government would draft a law to guarantee Ukraine’s spiritual independence, “making it impossible for religious organizations affiliated with centres of influence in the Russian federation to operate in Ukraine.”

“There are two columns of attack ongoing in the country; one which is led by the Russian army, at war with the people, and another battling for the souls of Ukrainians in Ukraine.”–Gene Maximiuk

Maximiuk believes the war is being played out on two fronts.

“There are two columns of attack ongoing in the country; one which is led by the Russian army, at war with the people, and another battling for the souls of Ukrainians in Ukraine.

“The raids were important in exposing a subversive element within Ukraine. There is a branch of Ukrainian Orthodox that has allegiance to the Moscow patriarchate and have been openly supportive of the Russian Orthodox Church,” he explains.

For a religious person, their beliefs are the essence of who they are, Maximiuk says.

“So you are attacking the core of the person,” he says. “It is a ruthless and manipulative thing to subvert the true message of the gospel to meet the political aims of a totalitarian autocratic hypocrite. It is unconscionable.”

MIKE DEAL / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS “The need for compassion and prayer is paramount.” says Father Gene Maximiuk.

But he stresses the need to remain open to parishes, parishioners and clergy who are seeking to leave the influence of the Moscow Patriarchate.

“There are things going on behind the scenes that we don’t know about. There have been overtures made to somehow join with the Orthodox Church of Ukraine, to create one Orthodox Church of Ukraine, independent and for Ukraine.

“The need for compassion and prayer is paramount.”

Whilst the Orthodox church in Canada is spiritually affiliated to the one in Ukraine, it has no church-specific political ties.

“The Ukrainian Orthodox Church of Canada was created in 1918 as its own entity, its own church,” Maximiuk explains. “We were created in parliament, we have a charter, our bylaws are specific to us. We do not take direction from Ukraine.”

“Families will celebrate to whatever level they feel comfortable with, whatever their emotions and circumstances are at the time.”–Gene Maximiuk

This Christmas will be a hard one for many Ukrainian newcomers, he concedes. The church will play its part in making the newcomers feel welcome by giving them something familiar that they grew up with to hold on to.

There will also be a potluck lunch at Holy Trinity after the Christmas service, which is led by Metropolitan Ilarion, the archbishop of Winnipeg.

“Families will celebrate to whatever level they feel comfortable with, whatever their emotions and circumstances are at the time. We know that families are not as happy as they could and should be, but in the same vein we still want to present that message of hope and bring people together. We want to let them know that they are not alone during this time.

“We have still decorated our churches; we will sing Christmas carols. We will still gather and wish each other well and we will continue to pray for each other here and in Ukraine.”

For Poliezhaieva, as much as this Christmas is about keeping traditions for her children, it’s also about being thankful for the friends she has made here, and for the support of the Ukrainian community.

She is also grateful that her family, both here and in Kyiv, is safe.

“We are preparing Christmas food, candles and meeting our friends here and spending time together. I am determined to go to church for service. I want to light candles for my relatives who have passed away.”

Her wish is that the war will end soon and that she will one day be reunited with her relatives in Ukraine.

“Keep looking towards the Bethlehem star. That message of hope has to always be the message that prevails, in this situation and in many situations.”–Gene Maximiuk

Maximiuk points out that the Christmas message is one of hope for all.

“Ukrainians are resilient; people have been trying to wipe us off the face of the earth for centuries. We are resilient and we are patient and there is that sense that things will get better. We will do what we need to do to help our families cope.

“Keep looking towards the Bethlehem star,” he exhorts. “That message of hope has to always be the message that prevails, in this situation and in many situations.”

On Sviat Vechir, Orysia Ehrmantraut’s grandchildren are tasked with looking out for that first star. It’s something they look forward to doing, a tradition she has continued from her own childhood.

“It is the job of the children to find that star. When it appears that heralds the beginning of the celebration. In all my years, since I have been little, there has always been a star. Even when it’s cloudy, the clouds will break and there will be a star.”

av.kitching@winnipegfreepress.com

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.