Persevering ink Free Press has been on the beat for a century and a half, and counting

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 22/07/2022 (1327 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Thousands of people, but only one wearing a straitjacket.

February 1923. Thirty feet in the air, hoisted up by his ankles. Head facing down. Dangling from a beam. Swaying like a pendulum. Thirty feet above the crowd. One false move, and he would land on his head and crush his skull. One misplaced wriggle, or one errant motion, and he could have plummeted right then and right there to his death. The world’s greatest escape artist, flattened on a Winnipeg sidewalk.

Imagine the copy in the next day’s newspaper:

HOUDINI DIES: ESCAPE ARTIST FALLS FROM FREE PRESS BUILDING

“The escape artist Harry Houdini died in Winnipeg Wednesday afternoon, falling to the ground during an attempted escapist feat here.

Houdini, who achieved world renown for his antics, magical illusions, and Vaudevillian performances, had been in Winnipeg for a series of performances at the Orpheum Theatre, but in a matinée performance, challenged by the Manitoba Free Press to do so, suspended himself upside down from a beam affixed to the Free Press headquarters, located in downtown Winnipeg, on Carlton Street.

Wearing a straitjacket, Houdini attempted to liberate himself from his restraints before tossing them to the ground from 30 feet in the air … ”

Houdini didn’t die. His final exit would come three years later, in Detroit on Halloween, age 52. The day after his feat of derring-do in Winnipeg, there was no feature story in the Manitoba Free Press: journalism was different then. There was mostly news, notices, wire stories and advertisements. But the moment of the great escape was captured in black and white by dozens of flashing bulbs, the most famous of which belonged to L.B. Foote, the city’s greatest early pictorial historian.

Building upon a proud history

An ongoing series celebrating the legacy of your Free Press

Wool coats. Wool caps. Fedoras. No bare heads. People climbed on top of automobile roofs. Everyone looking at the hanging man. A cold day in February. Downtown Winnipeg, filled with pedestrians waiting to see a rabbi’s son from Hungary yet again defy death and gravity. Four or five men pull with all of their strength on Houdini’s rope to keep him aloft.

A few windows in the Free Press building are open, with a group of people who might be reporters angling their heads out to get an unparalleled view of Houdini’s struggle from nearly his eye-level: were they hoping he’d fall?

Ninety-nine years later, every single person in that picture is dead, barring a miracle of genetics. Every man who pulled Houdini’s rope. Every police officer who rigged up the escape. Every reporter. Every editor. Every copy boy. Every newspaper hawker. Every subscriber. Every onlooker. Gone.

But the building at 300 Carlton is still there.

And so is the Free Press.

● ● ●

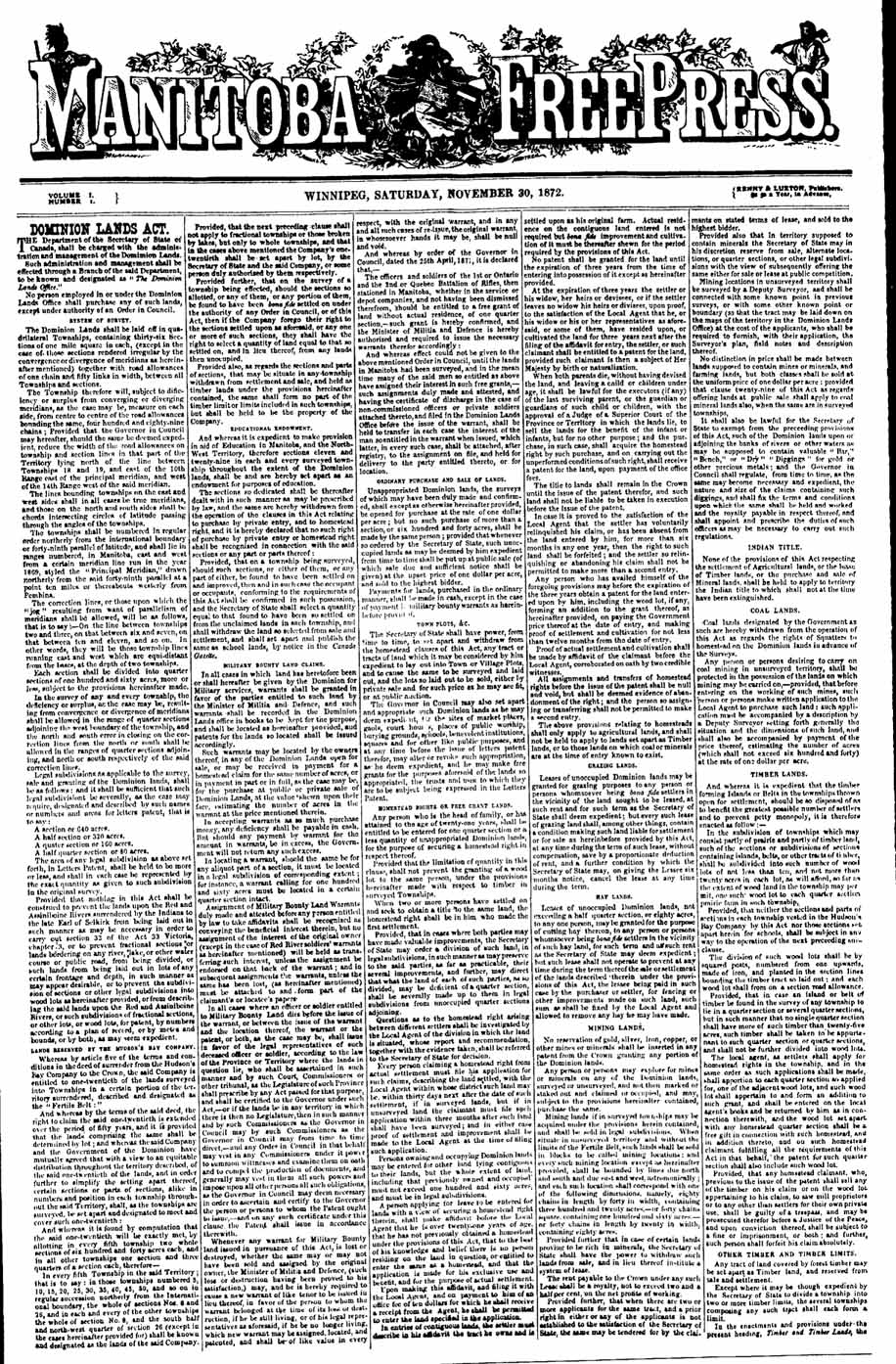

It had been around for 51 years before that. It all started in November of 1872, before the city of Winnipeg was called the city of Winnipeg, a decree which would not be made until 1873. The paper is older than the city itself. Do cities make newspapers, or do newspapers make cities?

A teacher named Luxton and a man named Kenny, who had $4,000 to invest, joined forces. They bought a printing press from the mecca of print media — the New York of Joseph Pulitzer’s World, and of Raymond and Jones’ nascent rag, the Times — and had it floated up the Red River on a steamboat in October 1872. A Twainian origin story.

A Dickensian addendum: the first publishing house was inside a wooden shack at what is now the corner of Main Street and James Avenue. Both men lived upstairs, Luxton with his family and Kenny alone. They turned the press by hand.

Everything was by hand: the writers wrote their copy by hand. Each letter was set by hand. The pages were laid out by hand. The papers were delivered by hand. It was hard work, easy to make a mitsake. (Imagine the penmanship and skill needed to avoid making a typo like that one every single day, in every other sentence.)

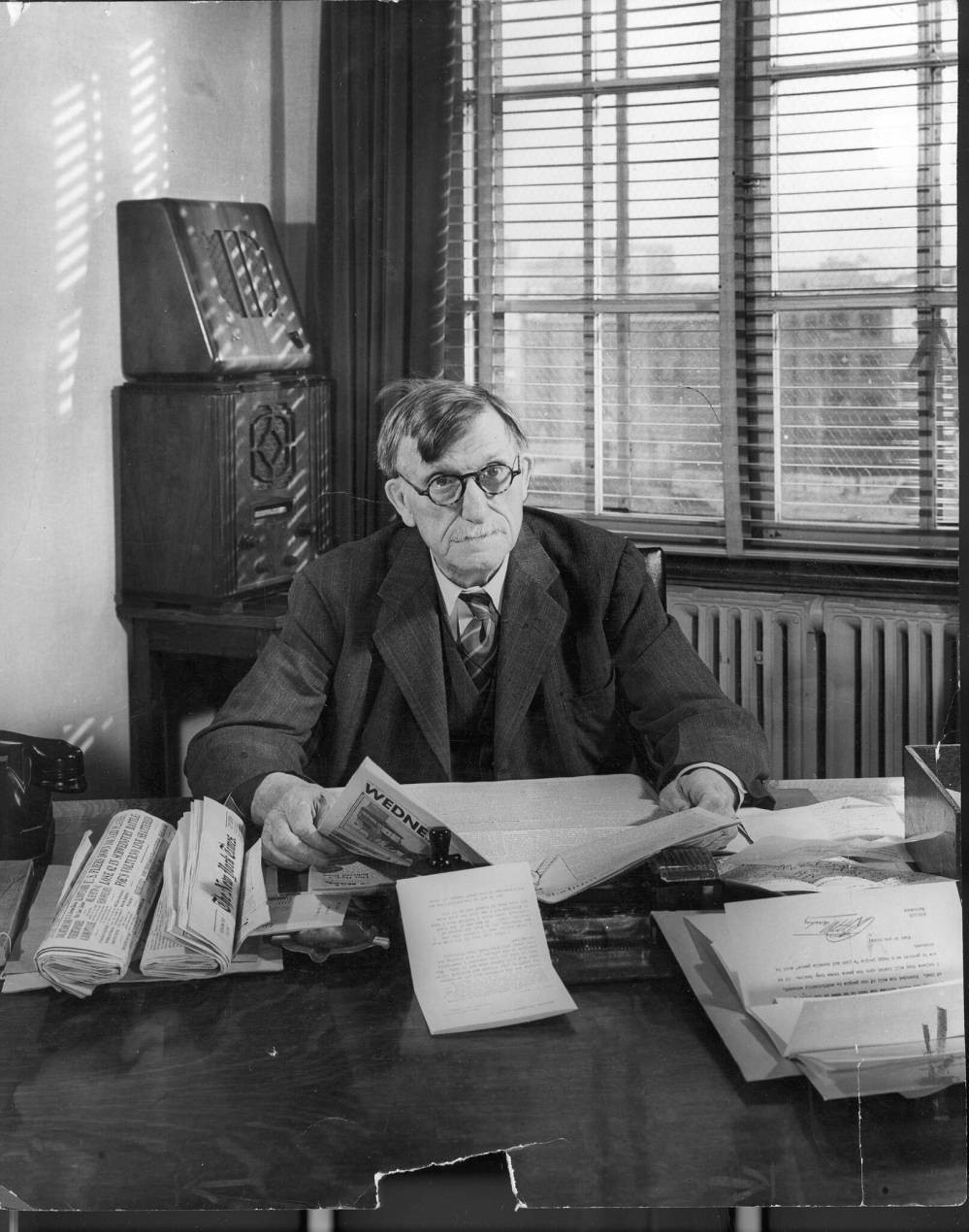

Other newspapers had started and ended, as documented in an article for the Manitoba History Services transactions in 1946, published posthumously under the byline of the famed Free Press leader J.W. Dafoe, who steered the publication from 1901 to his death in 1944, becoming in the interim the most famous journalist in Canada, before or since.

In 1872, Dafoe writes, something bad happened: dominion elections were held, and someone “monkeyed” with the voters’ lists; many Canadians were not allowed to vote. “They could wreck the newspaper offices, however, and they wrecked them all so thoroughly, with the exception of the Manitoba Liberal, that it took them months to get going again.

“During this interregnum the Free Press decided it was an opportune time to be born,” he wrote. “And though many other papers have come and gone since, it has refused to die.”

It started as a weekly. Two years later, it went daily with an evening edition. Competitors cropped up in the coming decade: the Nor’Wester, the Daily Herald, the Daily Tribune, and the Daily Times. The News Letter, the New Nation, the Manitoba Gazette. The Manitoba Telegraph, the New Sun, the Daily Sun, the News. The Daily Times. The Manitoba Daily Herald. The sharply but confusingly named Quiz. The Standard, run by Molyneux St. John. Dafoe on St. John: “There is a fine name for an editor!”

All of these except the Free Press and Sun lived short lives, early newspaperman and Nor’Wester founder William Coldwell said during an address to the Winnipeg Press Club in 1885. They had “passed into the happy land where sheriffs are unknown.” They didn’t mature into adults. The luckiest of the papers struggled to make it past their 10th birthdays.

Not the Free Press. In November 1872, the first edition was being prepared. News editor Jack Cameron, a printer named Griffin, Kenny and Luxton. They set the type by hand.

November 30, 1872 — the first edition.

The one you’re holding in your hands, the latest.

● ● ●

One hundred and fifty years. Ten decades, and five more.

The morning and evening routine for over 54,000 days, for hundreds of thousands of readers. Stories written at one end of the spectrum in the same language but in different worlds entirely than those at the other.

The Red River Resistance hadn’t happened when the presses first churned. John. W. Dafoe was a six-year-old boy. Harry Houdini had yet to be born.

The production of a newspaper is often referred to as a daily miracle, if you believe in that type of thing.

Sometimes it arrives late. Sometimes, it gets there early. Sometimes, there are speillng misteaks, but the paper keeps arriving. The letters are still typed by hand, but on electrical keyboards connected to every fact one could dream of accessing. The wooden shack became a downtown building which became an office in a North End industrial park.

A lot has changed, but a lot hasn’t: the truth still matters above all else. Holding the powerful to account still matters above all else. The paper never was perfect, and it will never be perfect. It never claimed to be, either. The paper evolves as the world does, and makes sense of that evolution in real time. At its best, it gives amplification to voices that often go unheard. It strives for accuracy and honesty. It gives people the news — the sports, the business, the cartoons, the politics, the arts, the life — every single day, whether on real paper or on a glowing screen, trying to do the best job possible with a deadline ticking ever closer.

That’s not magic. That’s not a miracle.

That’s journalism.

ben.waldman@winnipegfreepress.com

Ben Waldman is a National Newspaper Award-nominated reporter on the Arts & Life desk at the Free Press. Born and raised in Winnipeg, Ben completed three internships with the Free Press while earning his degree at Ryerson University’s (now Toronto Metropolitan University’s) School of Journalism before joining the newsroom full-time in 2019. Read more about Ben.

Every piece of reporting Ben produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Friday, July 22, 2022 9:44 PM CDT: Corrects spelling of straitjacket

Updated on Tuesday, January 24, 2023 10:19 AM CST: Fixes formatting of factbox