King’s counsel Free Press editor played role in shaping Canada’s 10th PM

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4 plus GST every four weeks. Offer only available to new and qualified returning subscribers. Cancel any time.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 22/07/2022 (948 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

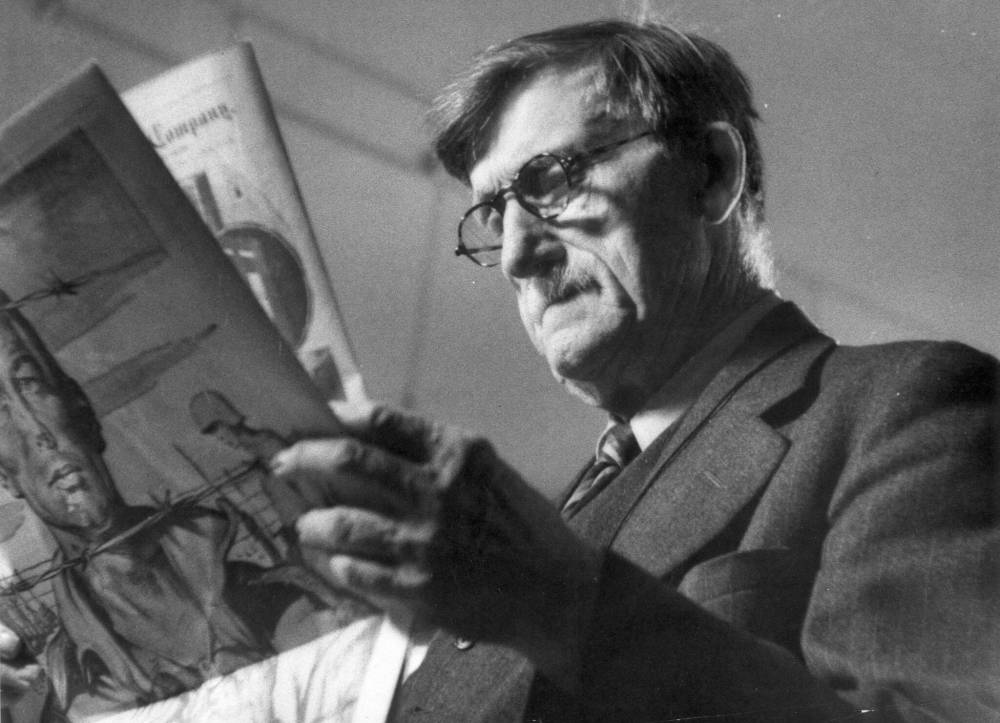

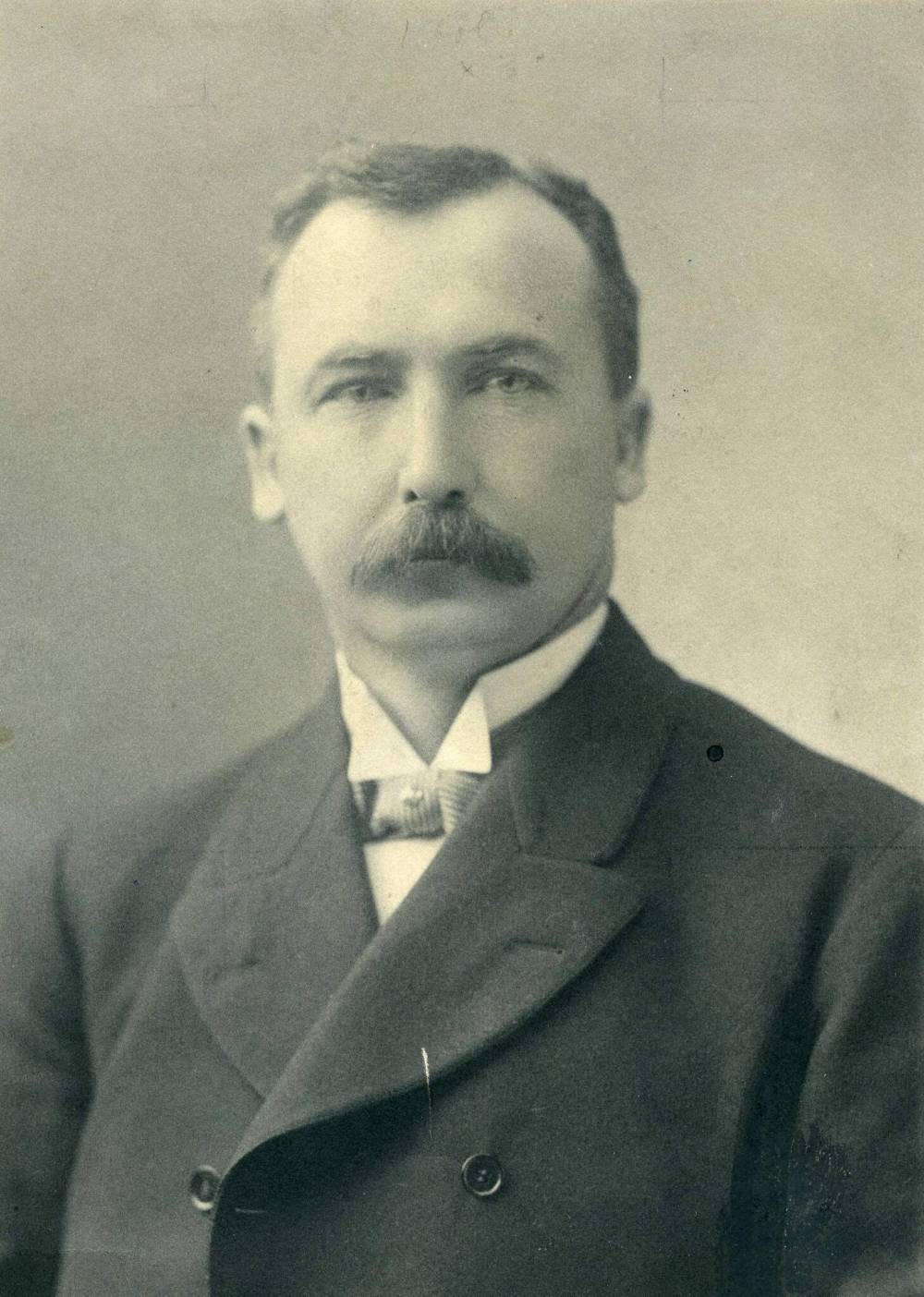

Like many Liberals and political commentators in 1919, the Free Press editor, John W. Dafoe, had concerns about the new leader of the Liberal Party, William Lyon Mackenzie King. Despite King’s prior experience as the deputy minister of labour and then as Canada’s first labour minister after he was elected a MP in 1908, the 44-year-old somewhat quirky bachelor did not initially, at least evoke a lot of confidence in some quarters.

In the 1921 federal election, the Free Press, a longtime supporter of the Liberal party, had instead favoured the farmers’ Progressive Party, which won the second-most seats in the House of Commons. For a time, King led a minority government and floated the idea of a Liberal-Progressive coalition.

Dafoe did not think that was a good idea. At the Manitoba Club, Dafoe was the unofficial head of the “Sanhedrin,” an elite group which also included Thomas Crerar, the reluctant leader of the Progressive Party, Bert Hudson, another prospective Progressive MP, Frank Fowler, a wealthy grain executive, Herbert J. Symington, a lawyer and railway executive, and lawyer James B. Coyne. Crerar took the group’s advice seriously and they steered him away from a King-led coalition.

At the same time, King, who regarded the Progressives as “Liberals in a hurry,” rightly concluded that the Progressives, if given the choice, would rather have a Liberal government than a Conservative one. And so King’s government was secure for the time being. Dafoe remained wary of King and privately stated he was the Liberals’ “poorest asset.” Dafoe insisted, as he told one acquaintance in 1922, that King’s “political amateurishness in view of the position he holds is almost unbelievable.”

Within a year, Dafoe’s view of King improved as he got to know him better. In the fall of 1923, King was preparing for the imperial conference in London where he would make the case for greater autonomy for Canada and other dominions of the British Empire. At the time, this was considered a controversial issue. Wisely, King sought out help from two individuals who thought about Canada’s relations with Britain as he did and who opposed a common imperial foreign policy — Oscar Skelton from Queen’s University and Dafoe.

Skelton was invited to accompany King as an “expert adviser” and within two years he was King’s undersecretary of state for external affairs. He served in the department for the Liberal and Conservative governments until his death in 1941, shaping the country’s foreign policy more than any other public servant then or possibly since.

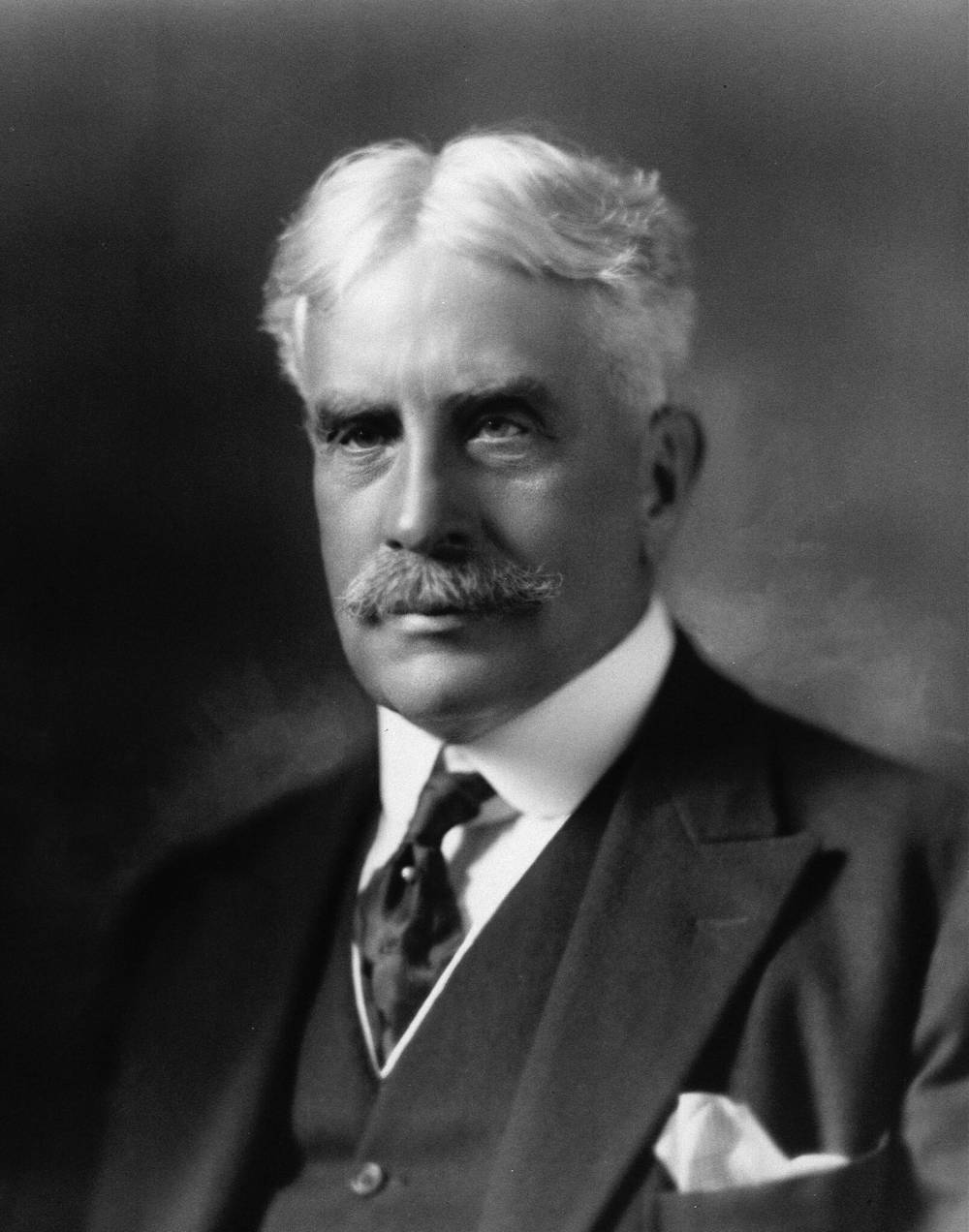

King also understood that any attempt by him to assert Canada’s autonomy was bound to receive bad press from British and Canadian Conservative newspapers. He urged several Liberal newspapers to send journalists to cover the conference and presumably slant the story in a friendlier and pro-Liberal fashion. He also requested that Sir Clifford Sifton, Free Press owner, send Dafoe to advise him. Despite the criticisms Dafoe had levelled at King, the prime minister knew Dafoe, as well as Sifton, shared his more liberal views on Canadian autonomy within the empire.

Moreover, King was aware that Dafoe had travelled with prime minister Robert Borden to Europe in 1919 to attend the peace conference at the end of the First World War and dispatched favourable reports to Canada. Then, too, Dafoe supported Borden’s efforts to push for Canadian autonomy within the British Empire and favoured the country’s independent participation in the League of Nations.

Yet he later conceded that his dual role as both journalist and representative of the Department of Public Information, a position he willingly accepted, often put him in an uncomfortable situation. Borden had no qualms about “arranging,” as he put it, for Dafoe to write a particular article he wanted disseminated to Canadian newspapers. Borden usually vetted Dafoe’s articles and dictated changes that were made. In this way, Borden tightly controlled the flow of information from Paris.

“These limitations cramped my style as a journalist,” Dafoe recalled more than two decades later. “There was no room for speculation, for deductions based upon assembled facts, or for racy descriptions of dramatic incidents, such as marked the proceedings at Paris. But what they lack in picturesqueness they gain in solidity — they are an authentic record of what went on in London and Paris to the extent that the principals thought it advisable to make the facts public at that time.”

While Dafoe was thus apprehensive about repeating this experience with King, Sifton was more enthusiastic. “You could undoubtedly have great influence with King,” he wrote to Dafoe, “and might conceivably exert a determining influence on vital matters.”

Dafoe was not as certain. “I have very little confidence in King,” he told Sifton. “I am afraid his conceit in his ability to take care of himself is equalled only by his ignorance and I should not be surprised if he should find himself trapped. I have no intention of becoming an unofficial member of a board of strategy to assist him while the Conference is on.”

Despite these initial reservations, Dafoe agreed to accompany the prime minister, Skelton and the members of the small Canadian delegation. Dafoe might not have wanted to become King’s unofficial adviser, but once they were on the ship in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, that’s exactly what happened. Next to Skelton, there was likely no one else whose advice King valued more. In the end, King’s performance at the conference and his fortitude in sticking to his nationalist principles sufficiently impressed Dafoe.

The 1923 conference was a (very) small step toward Canada achieving autonomy in its foreign affairs. The truth was that in his words and actions in London in 1923 King had hardly disowned the empire or Canada’s commitment to the empire’s welfare. When there was real danger, Canada would be there as it had in 1914 and as it was to be in 1939 with the outbreak of the Second World War.

King returned to Canada confident his personal reputation and political worth had much improved. Even Dafoe had grudgingly conceded that, “as for King, my regard for him has perceptibly increased by what I saw of him in London. He is an abler man than I thought; he has more courage that I gave him credit for,” Dafoe wrote to a friend. He added, however, what may be one of the great backhanded compliments in Canadian political history: “In the right setting and with the right men behind him, King would be a not unacceptable party leader.”

As the initial success of the Progressives faded — some of the party’s members later joined the new Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), the predecessor of the NDP — Dafoe had no choice but to support King against the detested Conservatives led by Arthur Meighen and then R.B. Bennett. In King’s celebrated feud with Gov. Gen. Viscount Byng in 1926 — in which Byng rightly refused to grant King a dissolution of Parliament so he could call an election — Dafoe sided with King and railed against Meighen and Byng’s actions. But privately, Dafoe believed King’s political career was over. He was wrong.

When an election was held in September 1926, King prevailed, somewhat to Dafoe’s surprise. Meighen, on the other hand, was furious with Dafoe and never forgave him or the Free Press for the treatment he had received. A few days after the election, Dafoe told John Willison, a prominent Ontario editor, (in words with more meaning than he could have ever imagined given King’s fascination with spiritualism), that, “the angels are certainly on the side of Willie King. He has a finer opportunity now than he had in 1921, and I hope he will be equal to it. I am beginning to think that probably he will measure up to his opportunities this time.”

Though King lost the next election to Bennett and the Conservatives in 1930, he regained power in 1935 and remained prime minister until he left office in 1948. And Dafoe, until his death in 1944, continued to support King, especially in the first years of the Second World War when King was under tremendous pressure to impose conscription (or the draft).

During a recruiting drive trip out west in the early summer of 1941, King was able to find a few minutes to meet with Dafoe and his associate George Ferguson (who became Free Press editor after Dafoe died).

“The Chief had a few minutes with Billy King,” Ferguson reported back to Grant Dexter, Free Press correspondent in Ottawa, on July 12. “Told him bluntly that if K. were opposed to conscription on principle, the FP would not follow him. K. assured the Chief that this was not so, that if we needed conscription to meet the needs, we’d tackle it.” The prime minister also raised the possibility of an election or referendum on the issue. Dafoe was not keen on either, but he was not about to abandon the Liberals because in his view the alternative, a Conservative government, was far worse.

Partly adapted from King: William Lyon Mackenzie King: A Life Guided by the Hand of Destiny.