The birth of a party organ

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$19 $0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for four weeks then billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Offer only available to new and qualified returning subscribers. Cancel any time.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 21/07/2022 (889 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Canada’s early prime ministers, including Conservative John A. Macdonald and Liberal Wilfrid Laurier, spent a great deal of their time not only cultivating positive relations with the press, they also offered financial incentives — often done secretly — to ensure that editors would toe the respective party lines. While there were a handful of truly independent newspapers in the decades after Confederation, partisanship was endemic in most aspects of life into the 1950s. Whether you were a Conservative or a Liberal dictated your personal and business relationships and certainly which newspaper you read.

Politicians understood the value of supportive editorials and slanted headlines and news reports, and did everything in their power to assert their control — going so far as to fully back party stalwarts who established newspapers and, in some cases, to be shareholders in these ventures as well.

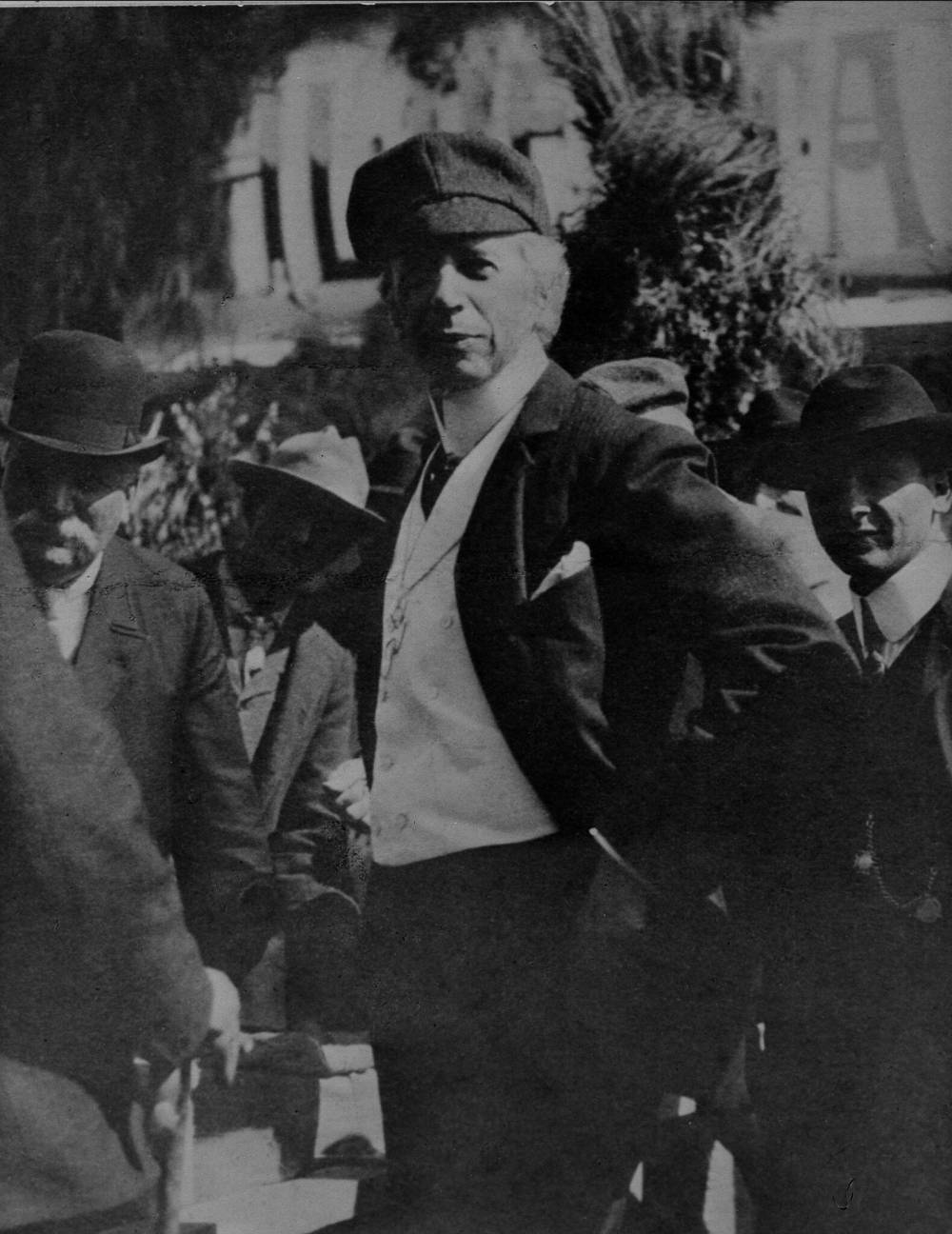

One politician who played a key role in advancing Liberal Party interests was Clifford Sifton, who served as the minister of the interior from 1896 to 1905 in Laurier’s government. Sifton, who had grown up in Brandon, is best remembered for his open-door immigration policy by which he welcomed mainly western and eastern Europeans — “stalwart peasants in sheepskin coats,” as he later referred to them — to settle and farm Western Canada. Yet, he was also a skilled and cunning political organizer and manager. In 1896 at the age of 35, he was wealthy, handsome, impeccably dressed and full of himself (the Conservative Calgary Herald usually spelled his name “$ifton”).

Sifton, who became a lawyer in 1882, was first elected to the Manitoba Legislature in 1888. He was appointed attorney-general in premier Thomas Greenway’s cabinet three years later. He used the Brandon Sun, a newspaper in which he held shares, to promote his career. In 1896, he jumped to federal politics after he was acclaimed in a Brandon byelection and joined Laurier’s cabinet. Following a dispute with Laurier over religion and schools in the new provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan, he resigned from cabinet in 1905 but remained an MP until 1911.

As a loyal and devoted Liberal, Sifton believed that suppressing news about the rival Conservatives was both smart and practical. Editorials and articles were churned out and dispatched to Liberal newspapers across the country where they were usually reprinted with few questions asked. In turn, patronage dividends in the form of government advertising were used to keep newspaper publishers happy. It was by any measure a smooth-functioning propaganda machine.

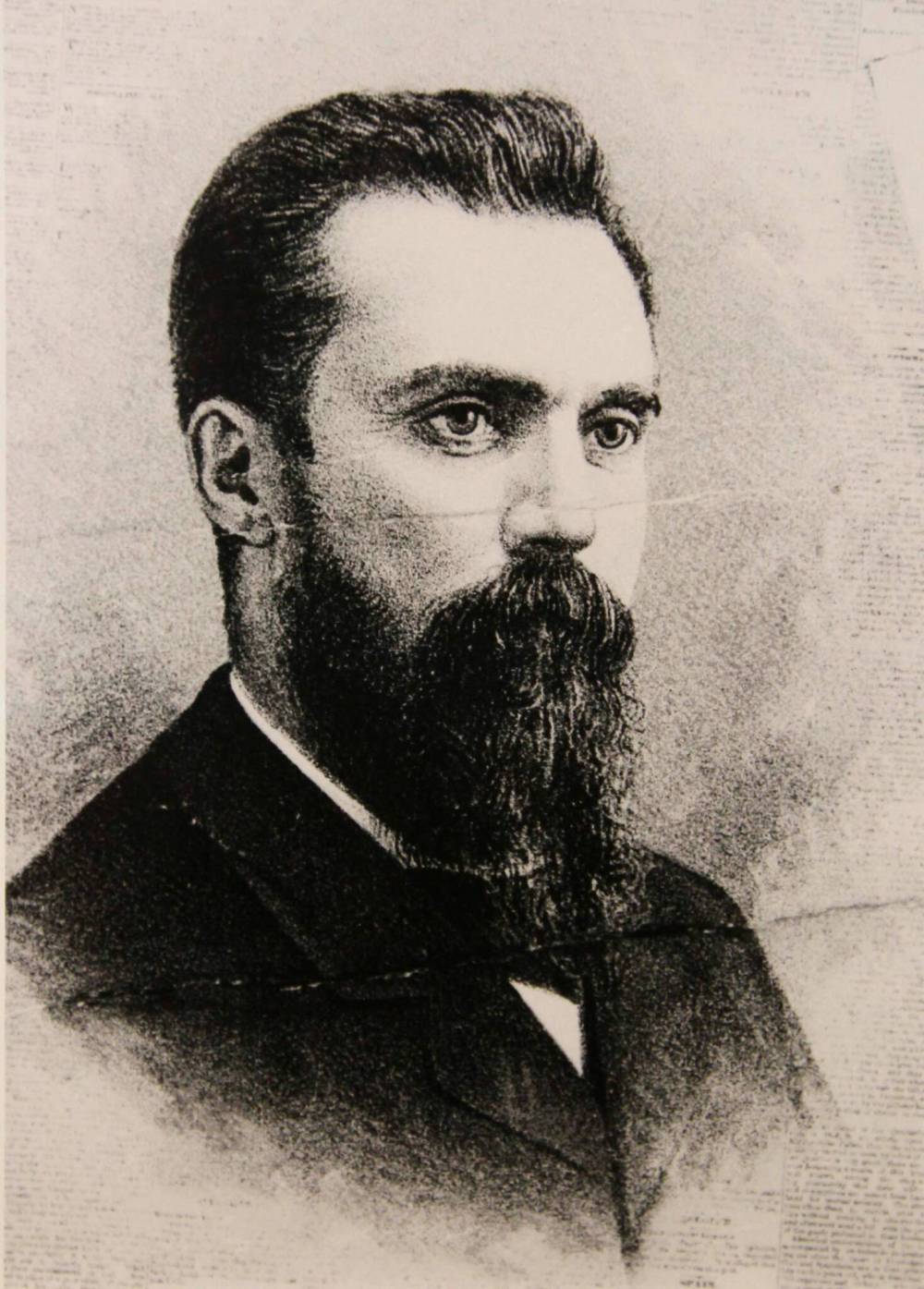

The Manitoba Free Press (as the paper was called until 1931) was Sifton’s prized jewel, which he had acquired in a shroud of secrecy. The Free Press had been established in 1872 by William F. Luxton, who had immigrated to Upper Canada from Britain with his parents in 1855 and had gained experience as a journalist and newspaper proprietor in several Ontario towns.

He moved to Winnipeg in 1871 (two years before it was incorporated as a city) when he was hired as a teacher, but in his heart, he was a newspaper man. He borrowed $4,000 from John Kenny, a retired farmer from Ontario and began publishing the Free Press as a four-page weekly paper that was loyal to the Liberals from its first issue. As the population of Manitoba increased, the paper prospered and by 1874 became a daily newspaper.

Luxton loathed political corruption and backroom dealings. He opposed the extension of French-language and educational rights and wrote critically about the power of the Canadian Pacific Railway. He wrote scathing editorials about the Conservatives and also eventually turned on the Liberal Greenway government for its alleged kowtowing to railway interests.

Needing capital, Luxton borrowed funds from businessman Donald Smith, long associated with the Hudson’s Bay Company and a prominent member of the syndicate to build the CPR. That was a mistake. The CPR’s president, William Van Horne, did not appreciate Luxton’s critical editorials and with Smith’s assistance took control of the Free Press after Luxton missed a payment on his loan. Luxton later operated the Daily Nor’Wester from 1893 to 1896. He worked as a journalist in St. Paul and then took a job with the provincial government as a building inspector. He died likely complications of a stroke in 1907, leaving his wife, Sarah, and their eight children.

Van Horne and Smith controlled the Free Press for five years. In a secret deal negotiated in January 1898, they sold the paper to Sifton for about $75,000 (approximately $2.5 million today). Sifton was motivated to purchase the paper because he did not trust Robert L. Richardson, the owner of the Winnipeg Daily Tribune, which was supposed to be supportive of the Liberals. However, Richardson, who was elected as an MP in 1896, regarded himself as an independent Liberal. He was banished from the Liberal caucus for continually challenging the party’s policies and hierarchy. Thereafter, Richardson’s Tribune was a bitter opponent of Sifton’s Free Press.

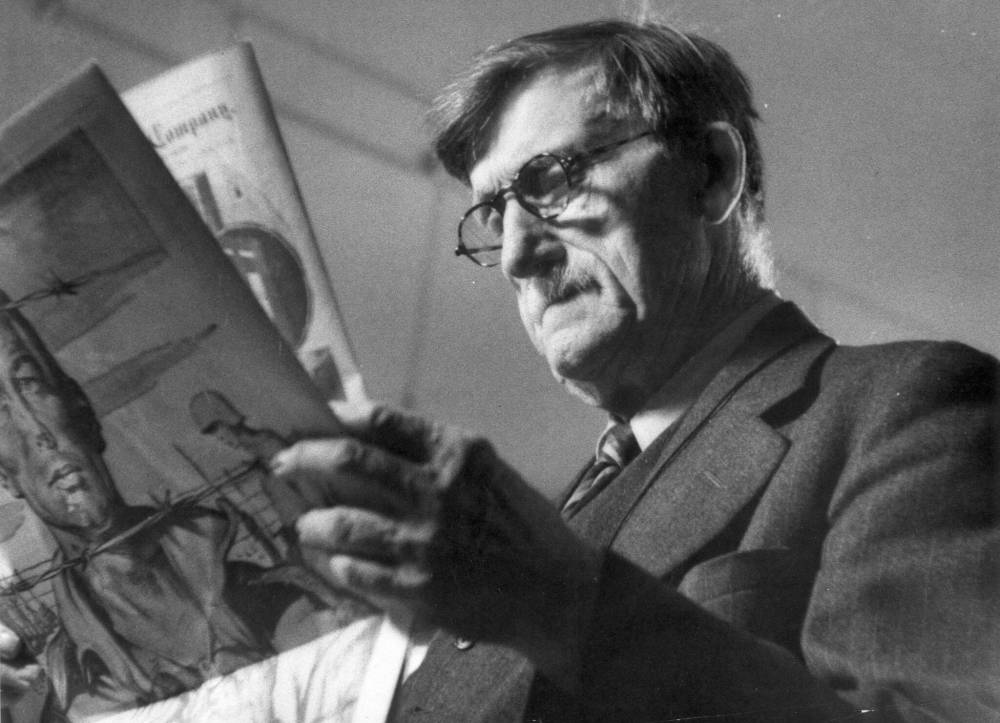

The first editor-in-chief Sifton hired was Arnott Magurn, who had worked as the Toronto Globe’s correspondent in Ottawa. But Magurn remained in Winnipeg for only a few years. In 1901, Sifton offered the job to the 35-year-old John W. Dafoe, who was to become one of the most significant and influential newspaper editors in Canadian history.

Dafoe’s long career in journalism started in 1883 with a job at the Montreal Star. Within a short time, he was working in the Ottawa press gallery covering federal politics for the Star. He also met Laurier, who immediately impressed him — as did the Liberal Party’s policies on social issues and national development. Asked once why he was so dedicated to the Liberals, Dafoe replied: “I think of all the sons of bitches in the Tory Party, then I think of all the sons of bitches in the Liberal Party, and I can’t help coming to the conclusion that there are more sons of bitches in the Tory Party.”

During the late 1880s, Dafoe worked at other papers in Ottawa and Montreal and did a six-year stint with the Free Press as a member of the editorial board before returning to Montreal. Dafoe admired both Sifton and Laurier, and was eager to become editor of the Free Press. At least for the first decade, Sifton called the shots. Dafoe “wrote what he was told,” journalist Pierre Berton wrote. “In those early years, he was as much a party hack as an editor.”

Nevertheless, under Sifton’s guidance, Dafoe and Edward Macklin, the newspaper’s business manager, built a successful enterprise. The Free Press truly was the leading voice of western Liberalism in Canada — though admittedly one that was partisan.

Over time, Sifton granted Dafoe a greater degree of independence. When they differed, for instance, in 1911 over the issue of reciprocity (a form of free trade) with the United States — which Dafoe supported, but Sifton did not — Sifton allowed Dafoe to back Laurier. However, this may have been purely a business decision on Sifton’s part, who wanted the Free Press to remain consistent in its editorial views.

After Laurier was defeated in the 1911 federal election and Sifton was no longer an MP, having opted not to run (during the campaign, he helped the Conservatives in Ontario), Dafoe gained even more editorial independence. The partnership between the two men worked. In any event, Dafoe remained loyal to Laurier until he broke with the Liberal leader over Laurier’s refusal to join a union government headed by Conservative prime minister Robert Borden during the First World War.

Sifton, who had backed Dafoe’s stand on the necessity of the union government, cautioned his editor about pledging allegiance to Borden. “The possibilities of the future,” Sifton wrote to Dafoe in October 1917, “hardly include the idea that the Free Press can support a party dominated by the Conservatives for any length of time and it might be awkward for you to feel that you had discussed matters too fully with the enemy.”

Dafoe heeded Sifton’s advice. But during the bitterly fought election campaign, the Free Press was unwavering in its support for Borden, conscription and the war. “Shall Quebec, which will neither fight nor pay, rule?” a Free Press editorial asked a week before the vote. From Dafoe’s perspective, the global crisis demanded a new political response. On the other hand, Laurier was so upset that Dafoe had for the first time campaigned against him that he contemplated starting his own morning newspaper in Winnipeg, though nothing came of that idea.

Some time after Laurier’s death in 1919, Dafoe wrote a series of feature articles in the Free Press (a long commentary on Oscar D. Skelton’s recently published two volume biography of Laurier) that was turned into his 1922 book, Laurier: A Study in Canadian Politics. At the end of the book, Dafoe recalled how he and others had tried to convince Laurier to change his mind about the Union government and extend the life of Parliament for the duration of the war. But Laurier, who feared losing Quebec to nationalists who were opposed to conscription, would not budge. It was a frustrating experience. Dafoe recalled spending an hour “in fruitless discussion” with Laurier “and coming out with the feeling that there was no choice between unquestioning acceptance of Laurier’s policy or breaking away from allegiance to him.”

Still, Dafoe’s overall assessment of Laurier’s leadership and influence on Canada was positive; he was merely honest about Laurier’s attributes and flaws. Laurier was, as Dafoe wrote, “a man who had affinities with Machiavelli as well as with Sir Galahad.”

Historian and writer Allan Levine’s most recent book is, Details are Unprintable: Wayne Lonergan and the Sensational Café Society Murder.