Class action There is no debate Manitoba students experienced significant learning loss during the height of the pandemic, the critical question now is how to close the gap

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 30/06/2022 (1352 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Not long after the final school bell of the day rang, Quinton Bresler once again found himself in a classroom.

The elementary schooler and his peers, of varying grades and skill levels, all have one thing in common on a recent Monday afternoon. None of them are particularly pleased to be here — a tutoring centre situated in a strip mall off Corydon Avenue.

Masks are optional due to the late June heat so tired expressions have nowhere to hide. Many of the children fidget with pencils at their desks while they quietly work through academic packages. One distracted girl glances around the room as she flips through pages of basic math problems.

“You’re on the last page!” exclaims instructor Mercége Martins, in an effort to refocus the young student on the final questions in her booklet for the day.

Here is a Kumon site in River Heights and Martins, a trained Manitoba teacher, owns the franchise.

The COVID-19 pandemic has produced potholes in every child’s education. The students enrolled in the after-school reading and math program are trying to patch them with her help.

The number of clients seeking remedial learning services has surged throughout the school year. While Martins welcomes the business attached to an uptick in calls from concerned caregivers, she called it “heartbreaking” to see students struggle with the consequences of inconsistent in-class learning because growing up is a tough enough task in and of itself.

“The kids I’m seeing now in 2022 are significantly more behind than what I saw pre-2020. Some of my Grade 8 kids coming in need to start with adding because they cannot do it without finger-counting or calculators,” she said.

Martins’ job requires much more patience than it did 27 months ago. She has witnessed higher-than-usual levels of student withdrawal, irritation and social anxiety in recent months — all of which the teacher attributes to a tough readjustment to traditional school routines.

Although Quinton said he feels more confident at school now than he did several months ago, he is not exactly ecstatic about all of the extra homework he will be assigned over the summer.

Jeff Bresler and his wife signed their son up for support in the wintertime due to concerns about lagging numeracy skills.

The Winnipeg father said he ensured Quinton, who just wrapped up Grade 5, logged on during stints of remote learning, but there was no shortage of distractions at home and teachers struggled — through no fault of their own — to keep learners on-track from afar.

“Not everyone has the means to do (Kumon), so we’re fortunate.”

Upwards of 200,000 students in Manitoba moved into emergency remote learning when Manitoba officials closed classrooms to the public after the first cases of COVID-19 were detected on the Prairies in March 2020.

It was only after Labour Day that K-12 learners were welcomed back for regular face-to-face lessons. Even then, physical distancing requirements created limitations and many teenagers studied on half-day or alternate-day schedules because their high school buildings could not safely accommodate all of them at once.

“Not everyone has the means to do (Kumon), so we’re fortunate.” – Parent Jeff Bresler

Further in-person class time was lost in early 2021 and 2022, as the province extended the Christmas break, citing fears of a spike in virus numbers. And then there were the Code Reds that shuttered schools for up to seven weeks in Winnipeg, Brandon, Hanover, Garden Valley and Red River Valley.

Positive cases and outbreaks also resulted in sporadic absences among students and staff. Countless classes had to suddenly upend their programming to go remote — a model that, at best, yielded mixed levels of attendance and participation.

“Even the greatest online teacher of all time was never hitting the mark as to what kids really need for learning to mean something and for them to retain it and apply it in a significant way,” said Alyssa Rajotte, a Winnipeg public school teacher.

“Everything” that is known about good teaching practice, ranging from the benefits of instant teacher feedback to group work, is incredibly challenging online, Rajotte said.

Limited adult oversight posed serious challenges to facilitating effective learning in a traditional sense. So did shoddy internet service and insufficient access to technology.

“Even the greatest online teacher of all time was never hitting the mark as to what kids really need for learning to mean something and for them to retain it and apply it in a significant way.” – Teacher Alyssa Rajotte

It is not a question of whether student academics have suffered, but rather what the extent and severity of the unfinished curriculum is.

Coined as “COVID learning loss,” the phenomenon is an extension of what has long been known as a “summer slide” of academic skills among students whose families cannot afford camps or museum trips to keep their children’s brains active when classes are not in session.

The Canadian research consensus is that learners typically lose the equivalent of one month’s worth of school-year instruction from the previous academic year, if not more, upon returning in autumn after the two-month break.

What is particularly concerning is that these losses snowball throughout a student’s career, said Tracy Vaillancourt, an education professor at the University of Ottawa, who chaired the Royal Society of Canada’s COVID-19 working group on children and schools.

“We scaffold the way we teach children so all of these deficits compound over time. They seem additive in the beginning, and then eventually become exponential,” the researcher said.

“We scaffold the way we teach children so all of these deficits compound over time. They seem additive in the beginning, and then eventually become exponential.” – Education professor Tracy Vaillancourt

Vaillancourt noted poor outcomes at school can predict things like increased substance abuse in adolescence and limited educational and job prospects later in life. Learning loss is not “inconsequential,” she said. “It’s a loss of their potential for the future, for the health and wellness of themselves and society.”

Canada is among a handful of economically advanced countries in the world that has not compiled a comprehensive report on learning loss because there are no nation-wide standardized test results to defer to in order to gauge how students are faring in numeracy and literacy.

In response to concerns about student mental health, Manitoba postponed its Grade 12 provincial exams early on in the pandemic. Around the same time, a series of standardized evaluations in Grade 3 (literacy), Grade 4 (French immersion), Grade 7 (mathematics) and Grade 8 (literacy) were halted.

“There’s a strong push against standardized testing in education and I can appreciate (critics’) points, but we also need to have some metric on students or on their learning, on their mental health, on their social-emotional development in order to know where to put resources,” Vaillancourt said.

A study conducted out of the University of Alberta found students who were in Grade 3 and under in 2019-20 — and in particular, readers who were already struggling — grappled with academic progress the most during the first school shutdowns.

“There’s a strong push against standardized testing in education and I can appreciate (critics’) points, but we also need to have some metric on students or on their learning, on their mental health, on their social-emotional development in order to know where to put resources.” – Tracy Vaillancourt

Education professor George Georgiou had been measuring reading scores of students in every grade from 1 to 9 in Edmonton public schools annually before the onset of the pandemic. In the fall of 2020, he surveyed more than 4,000 learners in each level to test their accuracy, fluency and comprehension once again.

After comparing the 2020 averages to the same data he had collected over the three prior years, he determined young learners’ skills were behind by roughly six to eight months.

Georgiou attributes the gaps to the fact that the youngest students in the school system were not yet independent readers, writers or learners when COVID-19 hito so their ability to participate in e-learning was limited.

Winnipeg’s Seven Oaks School Division has spent much of its recovery learning money on targeting young students and condensing class sizes between Grade 1-3. The division, in which approximately 11,600 students are educated annually, has hired 20 additional teachers for those early levels alone.

“The disruptions were more significant for the little kids and in a sense, they’ve got their whole time in school to recover — but if the kids who can’t read don’t have the basics in those early years, they are going to struggle to recover. The gaps will widen,” said superintendent Brian O’Leary.

“And where we know where those kids are, I think we’ve got a duty to get extra resources and extra help to those kids.”

O’Leary categorized academic progress across the board as “bipolar.” More than ever, teachers are finding there is no true average in their classroom because there are sizable groups that are thriving and struggling, he said, adding that existing disparities have widened.

Rajotte, a Grade 5/6 French Immersion teacher in Louis Riel School Division, said she has relied on both her professional judgment and colleagues even more than usual in order to find out where backtracking is required and necessary. It has been difficult to go “in-depth” into subjects since March 2020 because there is so much ground to cover, she said.

“It’s tough to give yourself permission as an educator to go deep (with student-directed, project-based learning) when the overall feeling in the world, I think, is ‘We have to catch these kids up!’ That’s a bit of a battle I have philosophically because shoving more things down their throats does not mean better learning,” she said.

Rajotte indicated that her lesson-planning has focused on taking every possible opportunity to immerse her students in French this year, given their oral pronunciation and confidence suffered when true immersion disappeared during distance learning.

Her division has been recording a notable downward trend in early years students’ French reading, writing and speaking scores, which had already been decreasing over time, throughout the pandemic.

“What I have seen is that learning loss is most pronounced in kids who have identified or were experiencing learning difficulties.” – School psychologist Vern Kebernick

By the end of 2021-22, Rajotte’s workspace resembled a standard classroom for the first time in a long time. Unmasked French chatter is once again frequent and desks no longer need to be at least two metres apart, but it is not lost on the teacher that appearances can be misleading.

Children have had to be so resilient throughout the pandemic and there have been minimal provincial dollars earmarked to support their academic and social-emotional needs coming out of it, she said, adding everyone would benefit from investments into smaller class sizes and more clinicians.

In some schools, resource teachers and other specialized staff have been redeployed throughout the pandemic to teach their own classrooms to accommodate two metres of spacing between desks. These employees, as well as their administrative and clinical colleagues, have also had to cover staffing shortages.

“What I have seen is that learning loss is most pronounced in kids who have identified or were experiencing learning difficulties,” said Vern Kebernick, a school psychologist in northern Manitoba.

Kebernick said one-on-one support was limited and students who require intervention have not necessarily been getting the attention they need because the resources that were already in short supply became nearly non-existent.

As dyslexia tutor Valdine Björnson puts it, “more people are in line for the same service,” than ever before. Björnson, who runs the Reading and Learning Clinic of Manitoba, said she worries that students with disabilities are at the very back of an extended line now.

A silver lining for Björnson is that the pandemic, combined with the recent release of an Ontario inquiry’s damning findings about literacy education failing students with disabilities in that province, have opened the door for frank conversations about improving reading instruction for vulnerable students.

The Manitoba Human Rights Commission is currently gearing up to launch a project to better understand local literacy issues and make policy recommendations to improve instruction for all learners.

Karen Sharma, acting executive director of the commission, indicated a growing number of residents have reported concerns about how reading is taught in Manitoba over the last two years.

“Students who needed in-depth supports due to a learning disability may have been left behind. The kinds of investments that need to be made and supports they need to receive in order to bridge that (gap) needs to be considered, post-pandemic,” Sharma said.

Manitoba students let out a collective sigh of relief when education leaders declared their grades would be frozen as of the last normal instructional day before the first of the COVID-19 classroom closures came into effect more than two years ago.

“The threat of failure was gone for a time being and I’m a little bit on the fence as to whether that was a bad thing, per se,” said Jordan Bighorn, co-director of the Community Education Development Association, an inner-city organization that runs alternative academic programs.

On one hand, Bighorn said the leeway allowed teenagers to shift their priorities to daily life, be it taking care of siblings or working to support families who were experiencing significant economic and mental health challenges.

On the other hand, students fell out of routines and disconnected from their academics, he said, adding efforts are underway to re-engage families in school communities across the city.

While there is minimal local data on student outcomes throughout the pandemic, Manitoba’s graduation rate remains on a steady incline. The context of that rise — from 81.9 per cent in 2019 to 82.6 per cent in 2020 and most recently, 83 per cent in 2021 — is that teachers have had to freeze marks and adjust expectations in recent years.

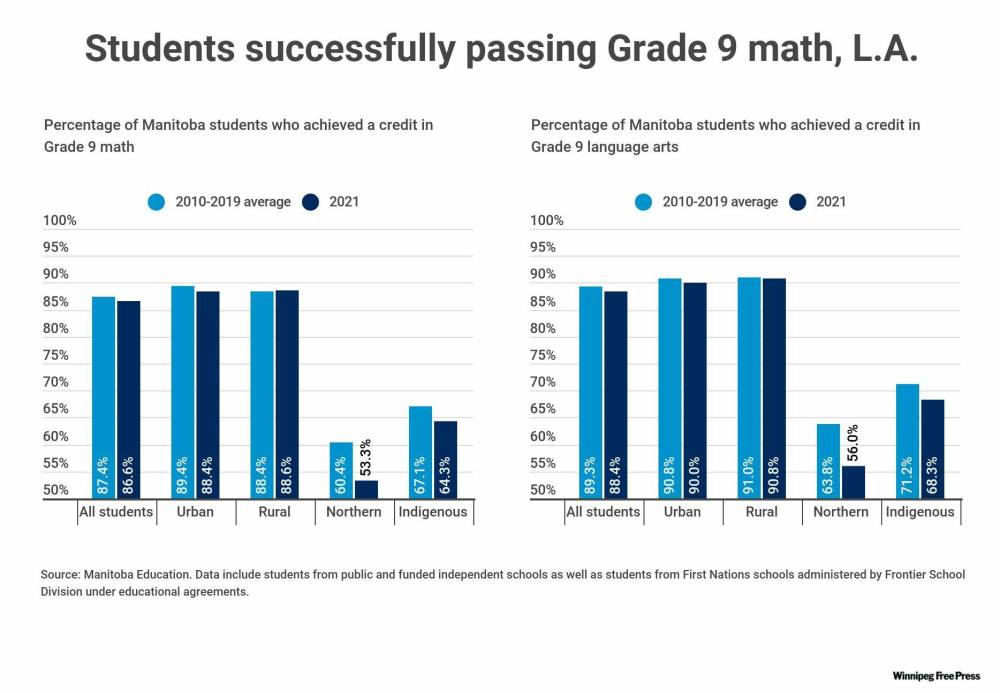

Meantime, there has been a minor drop in the overall percentage of first-time Grade 9 students obtaining math and English Language Arts credits.

Over the last decade, Manitoba’s average annual completion rates in those subjects have been 87.5 per cent and 89.3 per cent, respectively. The 2020-21 averages dropped by 0.9 percentage points in each category.

The gap is more significant among Indigenous students. Completion rates in both subjects were 2.9 percentage points lower last year in comparison to the 10-year average.

Math teacher Will Penner found that his Grade 8 students in east Winnipeg faced challenges with remembering what formulas and problem-solving strategies to use to answer problems this year so there has been much review.

“Knowing the basic concept of how to figure out the area of a triangle — you would think, generally speaking, by Grade 8 — would be ingrained,” he said, as he acknowledged that inconsistent in-class learning has taken a toll on students’ memories.

“We will catch up. That’s what we get paid to do. That’s what students are in school to do.” – Teacher Will Penner

Penner, however, is frustrated by all the talk of so-called “learning loss” because the term has a negative connotation and does not recognize how hard educators, caregivers and students have been working in spite of the COVID-19 crisis.

Many educators argue highlighting the subject only harms children who have been through a stressful two years, and it does not acknowledge the invaluable life lessons that have been acquired as a result of crisis management.

“We will catch up. That’s what we get paid to do. That’s what students are in school to do,” Penner said.

The principal of École Constable Edward Finney School echoed those comments. Karen Hiscott said there is no doubt sudden pivots to and from remote learning have taken a toll on academics and social-emotional development, but children have bounced back from learning disruptions tied to natural disasters, wars and other events throughout history.

The leader of the K-5 building in north Winnipeg said her message to teachers this year was — not unlike in other years: “We just need to meet children where they’re at.”

The social-emotional toll is much harder to measure.

Elementary school report cards include a 1-4 scale to signal how well a student understands and applies a concept, ranging from limited to “very good to excellent.”

Constable Edward Finney recorded a “negligible” increase of seven per cent more Level 2s across report cards this fall in comparison to 2019, according to Hiscott, who indicated educators reported that their students are now meeting grade-level expectations.

The social-emotional toll is much harder to measure. As children grappled with relationship-building and adjusted to being with peers at the start of the year, more conflicts than normal needed to be resolved in Hiscott’s office.

What the principal has found most surprising has been the need to rebuild student stamina for full-time in-class learning this year because elementary schoolers are exhausted. Some children have simply needed more time than others to readjust, Hiscott said.

For many students, this spring marked the first time they were in school until the end of the academic year since 2018-19 because 2019-20 and 2020-21 ended with city-wide classroom closures.

”It was a lot more stressful than it should have been.” – Student Brie Villeneuve

Being a member of the Class of 2022 has been a bittersweet experience for Brie Villeneuve. “It was a lot more stressful than it should have been,” said the senior at Grant Park High School, who uses they and them pronouns.

The Grade 12 student joked they dropped a world issues course this year because they were experiencing enough global problems firsthand. The teenager, who is immunocompromised, said they actually took the minimum number of courses required to graduate in order to reduce visits to a packed school because they were anxious about the ongoing threat of COVID-19.

“I definitely think that my education was put back, but not to the point that I’m clueless,” Villeneuve said, noting teachers have been frank about the fact they have condensed curriculum and skimmed over certain topics in recent semesters.

Combined, all of the disruptions have prompted the teenager to carefully consider how many courses to take during their first semester at the University of Winnipeg in the fall.

The last two years have required teachers to constantly ask themselves what is truly important and prioritize, said Cyril Indome, a physical education teacher at Windsor Park Collegiate. For Indome, that has meant shrinking a sizable unit on CPR training to allow for more discussion of mental health management.

“We’ve focused on building stronger relationships with kids. That might’ve come at the expense of the volleyball serve or the lay-up in basketball,” Indome said.

A non-profit dedicated to promoting healthy living across Canada gave students a D+ mark in overall physical activity in its 2020 report. The most recent evaluation from ParticipACTION indicated only 39 per cent of children and teenagers were getting an hour of moderate to vigorous exercise — the national exercise guideline for youth — before the pandemic began.

Exercise levels and outdoor activity dropped significantly during initial lockdowns, while time spent engaging in sedentary behaviour and sleep spiked, per the results of a follow-up survey conducted by the organization in April 2020.

While Indome indicated an increase in screen-time has resulted in improvements in students’ technology literacy, he said the downside has been youth are spending more time being sedentary and comparing themselves to others online.

The phys-ed teacher said there have been opportunities to build deeper relationships with students, given the pandemic resulted in smaller class sizes due to cohorts and physical distancing requirements. Some teenagers have disclosed personal challenges related to wellbeing and self-image.

In recent years, Indome has shifted nutrition lessons to emphasize the connection between physical and mental health, scrap the idea of “good and bad foods,” and explore positive relationships with food. His view is that a teacher’s job is to adjust to students’ needs rather than require them to fit into a certain model.

“We’ve focused on building stronger relationships with kids. That might’ve come at the expense of the volleyball serve or the lay-up in basketball.” – Cyril Indome

Over the last two years, the number of classroom teachers accessing the True North Youth Foundation’s mental health curriculum for early and middle years students has roughly doubled, from 2,000 to 4,000.

Known as Project 11, a tribute to former Winnipeg Jets player Rick Rypien who was outspoken about his mental health challenges and died of suicide in 2011, the proactive lesson plans aim to reduce stigma, promote empathy and equip students with strategies to manage anxiety and other challenges.

“We’re teaching students the importance of having an outlet, whether it’s reaching out to a friend or somebody that they trust, or maybe it’s putting some of their feelings down on paper because we know that struggles and hard times are inevitable,” said Suzi Friesen, the foundation’s director of educational programs.

Friesen said participants have shared their anxieties around falling behind at school, missing out on milestones, and anticipating sudden closures that isolate them from friends.

Approximately 150 high school teachers welcomed a 2022 Project 11 pilot for Grade 9-12 students, she said, noting that some educators indicated they have received disclosures about self-medication and self-harm.

Given there has been so much fear, owing to students swapping stories about COVID-19, consuming news reports, and experiencing grief firsthand, Friesen said teachers have been encouraging youth to focus on what is in their control — for example, making a healthy snack or exercising — rather than what is not. Learning how to breathe deeply is a key part of the program.

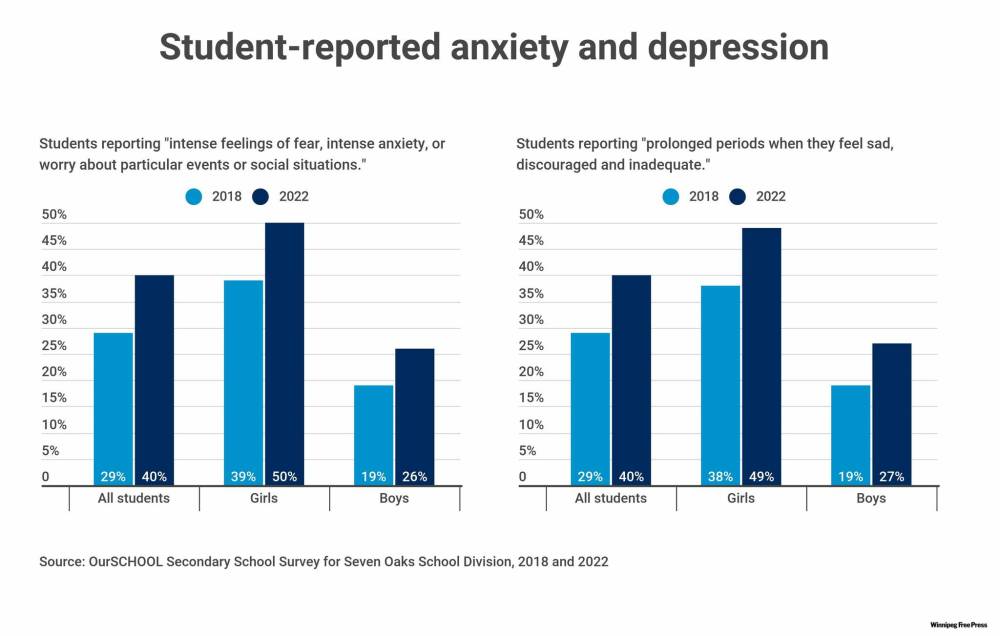

In Seven Oaks, the number of students in Grades 7-12 who reported having moderate to high levels of depression in a 2022 survey was 11 percentage points higher than the total who reported the same in 2018. There was a similar spike in students self-reporting concerning levels of anxiety.

The division participates in the national OurSCHOOL study every school year. In late 2018, approximately 3,400 students across 14 schools in Seven Oaks participated. The most recent statistics draw on data collected from roughly 2,700 respondents in 13 area schools in early 2022.

The data show 57 per cent of students feel a positive sense of belonging at school — 10 percentage points lower than before the pandemic. The number of students who indicated they were interested and motivated in their learning dropped by a similar margin, from 45 per cent to 36 per cent.

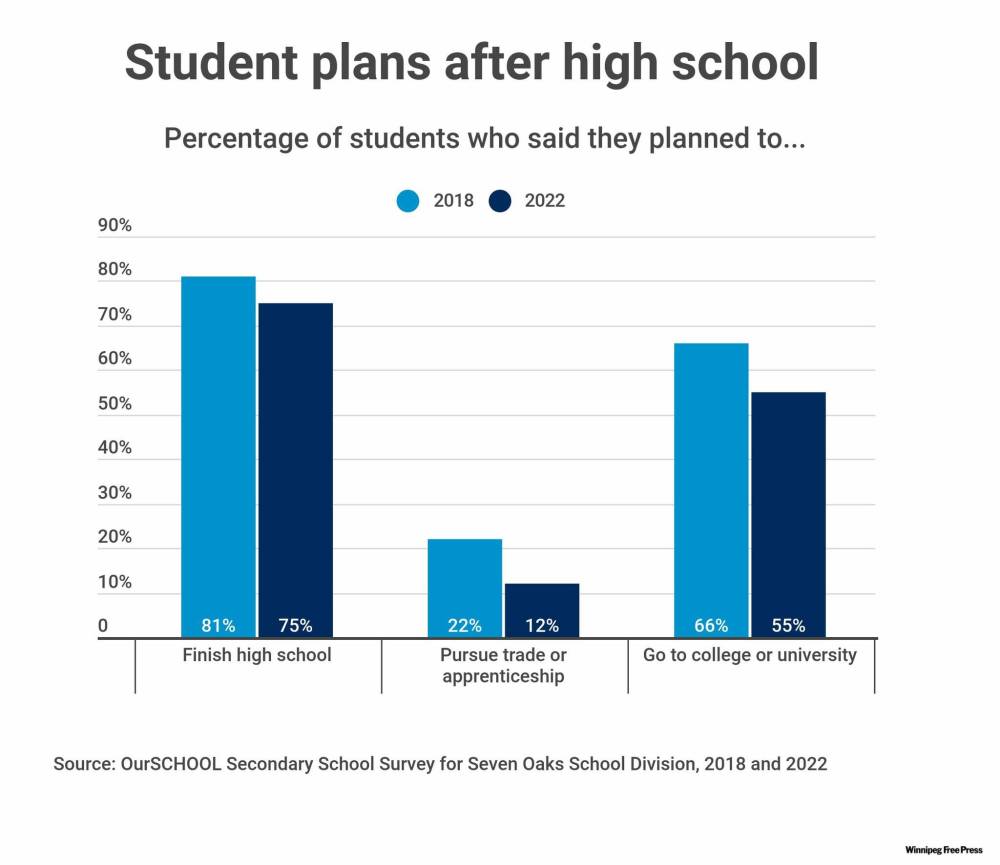

Fewer students are planning to finish high school and pursue post-secondary education overall, according to the recent survey results. At the same time, the division’s truancy rate, which represents the percentage of students who reported skipping classes or missing days at school without reason, has increased slightly.

The picture that emerges for the superintendent of Seven Oaks is that kids have been “languishing rather than thriving.” O’Leary said teachers have “recalibrated” their approaches in response.

Educators across the province have been more lenient about deadlines and accommodations. Stressful timed exams worth hefty grade percentages have been replaced with smaller assessments and summative projects.

The biggest readjustment amid a return of daily in-person classes and fewer disruptions in 2021-22 than in years past has been rebuilding traditional school culture and reminding students of the expectations that existed before COVID-19, said high school teacher Deondra Twerdun-Peters.

Twerdun-Peters, of Fort Richmond Collegiate, said her students have struggled with how-to balance schedules, stay motivated, and be good spectators at school events, among other intangible skills.

“Yes, there’s the curricular outcomes that have been lost — but for me, COVID learning loss has been the experience of kids losing the ability to connect with each other and how-to interact in different settings,” she said, adding the pandemic has only emphasized the importance of connection between students, as well as teachers and students.

In lower levels, early years teachers are discovering their young students are coming into classrooms without daycare experience and minimal interaction with peers due to pandemic concerns. Repetition has been critical to instill fundamental routines in students, from lining-up to getting along with peers to paying attention in class.

Following months of government press conferences during which officials have delivered stark news about virus cases, a rising death toll and public health orders that shuttered businesses and in-person instruction, Education Minister Wayne Ewasko sets a different tone on a mid-June day.

Ewasko smiles as he greets the guests who have gathered at Sansome School, with a background of elementary students whispering among each other at their desks. There is only a single digit number of days on the academic calendar and tired teachers and students are ready for a vacation.

A total of $20 million in provincial support will go towards remedial learning efforts, ranging from improving school readiness to literacy and numeracy initiatives. The one-time injection is the equivalent of roughly $100 per K-12 pupil in the province.

Critics take issue with the reality that one-off announcements do not offer consistency and K-12 funding has not kept pace with inflation for several consecutive years.

There are also countless questions that remain unanswered around how the province plans to replace the education property tax revenue that divisions have long relied upon, as the government sends homeowners rebates and phases out the fee.

“Education is really traditional and in a way, COVID derailed that and it forced innovation.” – Tracy Vaillancourt

The president of the Manitoba Teachers’ Society likened the latest funding announcement to “firefighting.” Union leader James Bedford said the sum will not address long-term issues, including large class sizes and substitute shortage, in an underfunded system — let alone new ones related to learning loss.

Research is currently underway in the education department to build a comprehensive understanding of the impacts of the pandemic on student learning and determine common themes across the province.

Pre- and mid-pandemic report cards, absences, elementary level assessment results, credit attainment, graduation rates, and administrative information, such as student characteristics, geographic location and socio-economic factors, will be analyzed, according to the department.

“Education is really traditional and in a way, COVID derailed that and it forced innovation… In 10 years, what we’re going to know is that this either improved learning or was a huge hindrance to learning, but we won’t know for quite some time,” said Vaillancourt, of UOttawa.

“What if this was a shake-up that needed to happen? I’m open minded.”

“The pandemic has provided an opportunity for educators, including those in the (bachelor of education) program, to re-envision what we do as educators, why we do it and how we can do better.” – Associate professor Martha Koch

Martha Koch, an associate professor of K-12 curriculum, teaching and learning at the University of Manitoba, said the novel coronavirus has influenced how the education faculty trains its teacher candidates.

The crisis has prompted conversations about equitable access to digital learning, heightened awareness of student rights to privacy as they learn, and made teachers consider how they collaborate with families to support a child’s education, according to the associate dean of undergraduate and partnerships in the faculty.

“The pandemic has provided an opportunity for educators, including those in the (bachelor of education) program, to re-envision what we do as educators, why we do it and how we can do better,” Koch added.

Local school leaders will have flexibility on how-to use a significant chunk of Manitoba’s new recovery learning fund in 2022-23 — an acknowledgement that there are unique ideas and needs when it comes to patching potholes in education.

Hiscott said there is already an “all-hands-on-deck” approach at Constable Edward Finney that promotes a pathway forward that emphasizes academics, wellbeing and balance. “(Children) will be alright, as long as the adults are all right because they take their cues from us… If we’re worried and anxious, then that’s how they will be as well,” the principal said.

At the River Heights Kumon, Martins’ is not quite as optimistic.

The instructor’s belief is every school should start to regularly assign homework, especially among younger levels, so students can spend more time honing foundational concepts that they were not able to master because of COVID-19.

Learners are out-of-practice and it is showing in their messy handwriting, inability to concentrate for extended periods of time, and report cards, said the owner of the tutoring facility. “The last two years were very chaotic. I can promise you that if they learned it, they didn’t learn it properly,” she said.

Martins said she does not want children to be overwhelmed with study, but an additional 30 to 60 minutes in a 24-hour day is manageable and beneficial to both boost academic outcomes and study skills.

The text on the banners posted all over her academic centre put it simply.

“Practice makes independence.” “Practice makes confidence.” “Practice makes mastery.”

maggie.macintosh@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @macintoshmaggie

Maggie Macintosh

Education reporter

Maggie Macintosh reports on education for the Free Press. Originally from Hamilton, Ont., she first reported for the Free Press in 2017. Read more about Maggie.

Funding for the Free Press education reporter comes from the Government of Canada through the Local Journalism Initiative.

Every piece of reporting Maggie produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.