Paddlewheel dreams Big names, lively stories and a feud can be found in Welcome Aboard!, new memoir of the owner of the Queen and Princess riverboats

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 30/06/2022 (1350 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

A lot of men get old and retire and buy themselves a little boat as a reward. When Steve Hawchuk was 32, he bought not one, but two, massive cruise ships.

It was 1969. He was working a solid job for a concrete company, but when his brother told him the Paddlewheel Queen and Paddlewheel Princess were for sale, Hawchuk had trouble thinking of a reason to say no. He loved the river. He didn’t like his job that much. He liked, and still likes, his brother, who would become his business partner.

Hawchuk said yes, and before long, he was a riverboat captain, ferrying down the Red River guests both ordinary — the elderly Mrs. Hildebrand, who boarded each Saturday — and cartoonishly extraordinary.

“Col. Sanders was very nice,” Hawchuk says. The Kentucky Fried Chicken man looked just like he did on the bucket when he strutted aboard in 1977: white suit, white hair, white Fu Manchu.

Seven years earlier, the sitting prime minister, Pierre Elliott Trudeau, cavorted on the Queen while in town on official business. “I didn’t vote for him,” Hawchuk says. “But he was interesting to listen to.”

In those days, the river was the place to be. As many as 90,000 passengers took to the waters each season. Field-tripping school children, partying bachelors and bachelorettes, tourists and professional athletes — there were babas and there was Bobby Hull. The Queen and Princess were a nightclub and daytrip, wrapped into one nautical package, and for 44 years, Steve Hawchuk was at the helm, steering two ships through triumph and choppy waters.

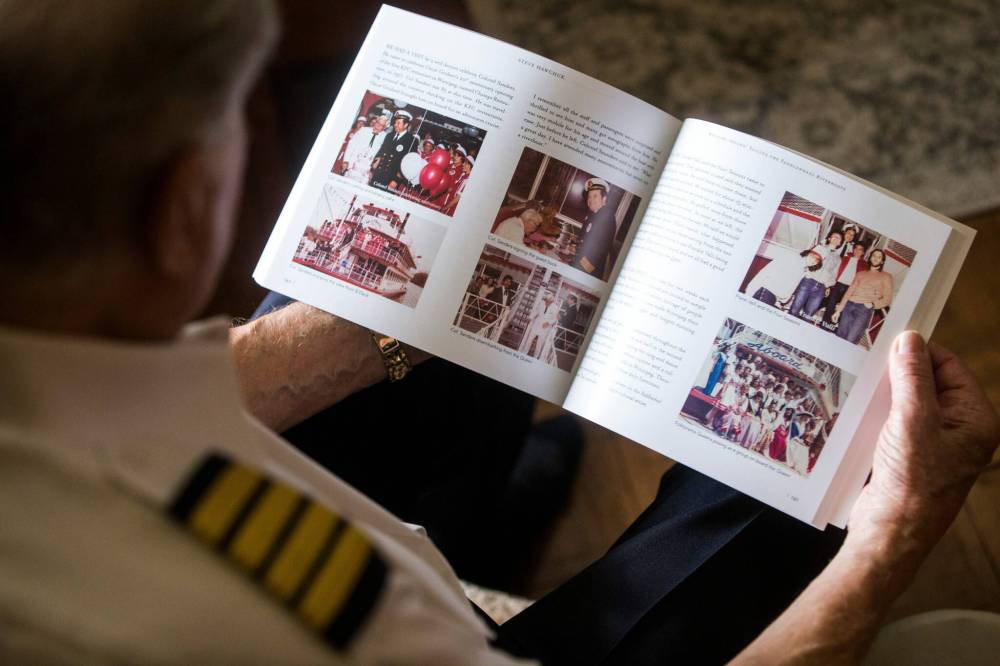

This was not the concrete business, and in a newly published memoir — Welcome Aboard! — Hawchuk shares some details of his captain’s log: lively parties, loud concerts, and even a naval war with a rival armada led by a bitter rival who didn’t mind playing a little dirty.

The riverboat business was not all fun and games.

It takes an eccentric to dream of building a riverboat, and that’s a good word to describe Ray Senft, who had Dobermann pinschers, a mynah bird, a Siamese cat, and a pet mule named Bert.

He started a successful construction company in the 1940s, when he was still in his 20s. But when he saw a pair of ships — the Mark Twain in New Orleans and the Huck Finn in St. Louis — doing brisk business as passenger vessels, the industrious Senft, a boat enthusiast known as Red River Ray, got a little twinkle in his eye.

Over 80 days in 1965, the Purvis Boat Company in Selkirk built the 92-foot, 400-passenger Paddlewheel Queen at a cost of $200,000. The next year, he gave the Queen a Princess as a younger sister. Two ships, going merrily down the stream.

But Senft was not alone on the water for long.

During the Queen’s maiden season, the snack services were managed by a man named Daniel Ritchie, another brilliant businessman who had run one of the city’s largest industrial catering companies, a restaurant chain called the Millionaire Drive-In, and the Snow Cap Drive-In on Nairn Avenue. Apparently seeing the potential boon on the water, Ritchie jumped Senft’s ship and built his own, contracting Purvis to craft a competitor for the Queen and Princess: the River Rouge.

“Someone can check me on this but oftentimes — I would say the majority of times — we had the idea first and then Ritchie would copy us,” Hawchuk writes. “We had the Queen first, and Ritchie followed us with the Rouge. We had the 200-passenger Princess first, and Ritchie copied it with the 200-passenger Lady Winnipeg. We launched Princess cruises to Lower Fort Garry, then Ritchie ran Lady Winnipeg cruises to Lower Fort Garry. We were the first to lengthen the supper hour and night cruises to three hours, instead of two; Ritchie followed soon after.”

It was like “miming in front of a mirror.” Ritchie even went so far as to challenge Senft in the pages of the Free Press to a riverboat race from the Redwood Bridge to the University of Manitoba and back. The race didn’t happen, but the war was on.

In 1967, royalty was on the line. A real princess was in town. Alexandra and her husband Angus Ogilvy visited Winnipeg for a brief spell that June, and both captains vied to carry her luggage for an afternoon. Ritchie’s ship was docked in Selkirk, and the water was too low for the River Rouge to leave. The princess took a trip to Kildonan Park on the Queen.

Ritchie called himself the Commodore, but had no naval experience. After Hawchuk and his brother — former member of parliament Joe Slogan — bought the ships from Senft, Ritchie would steer his in front of the Queen and Princess, nearly causing several collisions. “He just liked to get (Hawchuk’s) goat,” recalls former Paddlewheel captain John Wallis. “He said to me one day, ‘I just enjoy poking the bear.’”

At times, Ritchie’s poking was subject to criticism. And the bears were cubs.

In 1978, three teenagers were ashore above Palmerston Avenue, throwing crabapples at the Rouge. Two or three hit the boat. The boat rolled on, but then, in Hawchuk’s account, things turned sour.

“Once around the bend, (the ship) pulled into shore out of sight of the three male youths,” he writes. “The captain jumped off, snuck around behind the youths, and grabbed two of them by the arm. One got out of his grip but he managed to drag one youth back to the boat.”

A passenger said he saw the ship’s captain lift the 15-year-old aboard, where Ritchie pulled his hair, dragged him into the wheelhouse, and bound his hands and legs with rope; the teen was face-first on the deck for nearly two hours as the voyage continued. Ritchie was allegedly overheard saying, “If he moves, kick him.” it was Ritchie’s belief that the boys had thrown rocks, which endangered his passengers.

“That was the story they told to police detectives, and that was the story they would stick to throughout the courtroom trial that ensued,” Hawchuk writes.

“The captain jumped off, snuck around behind the youths, and grabbed two of them by the arm. One got out of his grip but he managed to drag one youth back to the boat.”

Ritchie faced charges of unlawful confinement, which carried a penalty of five years in prison. Some people saw his actions as barbaric; others said heroic.

A passenger named Edward Byrne, as recounted in Maclean’s in a 1979 report, testified to the provincial court that “by the time I got to the scene of commotion the boy had started to cry.” He was “disgusted by the whole thing” and when he tried to intervene, Ritchie “asked who the hell I thought I was and told me he was the authority on the boat.”

Ritchie played the victim: his ship had been pelted by everything from apples to stones to dead fish and pigeons that had been set on fire. He said he bound the boy’s ankles for his safety, “in case the youngster had tried to jump overboard,” Maclean’s wrote; that very thing had happened only one month earlier, and in another more serious hurling, a railway tie from the CN Rail Bridge landed on the deck.

The commodore and his captain were acquitted. “In my view,” Judge G.O. Jewers wrote, “not only were the accused lawfully entitled to make the arrest, they were absolutely right to do so. The actions of the boys were a threat to the ship itself — witness the broken window — and to the passengers, some of whom were on deck and liable to be injured by the objects hurled.”

As the commodore enjoyed a legal victory and a boost of publicity, not to mention a reasonably credible scare tactic to prevent copycats — he claimed objects were hurled much less often after the trial — the boys paid $25 fines for wilful damage of private property, and ordered to pay $25 in restitution.

Onto the Queen and Princess, things were often thrown. On one occasion, an errant fishing line hooked into the back of a passenger. On another, a grape Slurpee fell onto a bride and groom. Hawchuk recalls that they laughed and changed clothes.

“People are funny about bridges and dropping things,” Capt. Graham Cox told Hawchuk in an interview.

Though much fun was had aboard, there was a lot of sadness, and a fair deal of tragedy, Hawchuk writes. “Every summer we’d find one or two bodies floated up against our boat,” Hawchuk writes. “We’d arrive in the morning and see that unfortunate sight.”

It was a common occurrence to see people standing on a bridge, and sometimes, passengers of the boats themselves fell or dove into the water. In one captain’s first year at the helm of the Queen, 13 people jumped off into the powerful Red. No Queen or Princess passenger ever died, Hawchuk writes. But aboard the Rouge, one teen fell in the water at a high-school graduation in 1987, going overboard after a drunken argument with his girlfriend.

A lifeguard classmate leapt over to save his friend, but couldn’t find him in the river.

The commodore sold his ships in 1986, and in the 1990s, they came into Hawchuk’s ownership.

But by that point, the riverboat business was beginning to sink. After reaching a peak of 90,000 combined passengers on only two ships in 1980, the Queen and Princess, plus the newly purchased Rouge plateaued at 59,718 in the year 2000, sinking ever further after. 9/11 hurt cross-border tourism — a key feeder of riders — and water levels were too high to enjoy a full boating season.

In 2006, the last year all three ships were in operation, only 39,339 people climbed aboard. The Queen and Princess last sailed in 2013. The heyday was over.

The Queen was cut up for scrap. The Princess was sold and then lit aflame by four teens, destroying the ship, whose hull now rusts in the Selkirk Slough, next to the oxidizing skeleton of the River Rouge.

As for Hawchuk, he is spending his senior years the same way he spent his youth north of Selkirk: in a house overlooking the river.

“The boats are gone, but the memories are here.” – Steve Hawchuk

He spent two years writing the book, with editing by former Free Press reporter Bill Redekop. He also got some help reminiscing from several former captains, servers, employees and customers. Some former Rouge captains gave their reminiscences, including Esther Nagtegaal, who not only became an employee of Hawchuk’s, but is now married to him.

Hawchuk says it’s unlikely a riverboat boom will ever happen again on the banks of the Red: it would cost millions of dollars to build a ship, and the elements that contributed to the sinking of his ship’s fortunes have only worsened with time.

He does not boat anymore. He says he’s now too old for it. But he has his stories, and now, he has them compiled in a book.

It’s a part of his life he says he will always hold close, representing a different time in the city’s history.

“The boats are gone, but the memories are here,” says the 84-year-old captain.

All aboard.

ben.waldman@winnipegfreepress.com

Ben Waldman is a National Newspaper Award-nominated reporter on the Arts & Life desk at the Free Press. Born and raised in Winnipeg, Ben completed three internships with the Free Press while earning his degree at Ryerson University’s (now Toronto Metropolitan University’s) School of Journalism before joining the newsroom full-time in 2019. Read more about Ben.

Every piece of reporting Ben produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.