Deferred care, immediate pain Many Manitobans are left in medical limbo, unsure if they’re even on wait lists for intervention

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 24/06/2022 (1264 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Greta Morrill has been waiting several years for a new knee. She has been suffering with pain in her right knee since 2012.

Instead of surgery, Morrill, 73, has undergone three scoping procedures. It helped ease the pain in the short term, but her condition deteriorated over time. By March 2021, her surgeon confirmed by X-ray there was little to no cartilage left in her knee.

“I can feel when it’s rubbing and it makes a funny noise and that’s where the pain is,” says Morrill, who can barely walk and only manages to do so slowly with a cane. “It’s like bones rubbing together, it’s very painful.”

Like many Manitobans in her situation, Morrill has no idea when she’ll get surgery. The last time she phoned her surgeon’s office in April for an update, she was told no date was set. The best they could do was promise her she would be contacted two months before her procedure.

The uncertainty of not knowing when she will get surgery is the hardest part, Morrill says, as her condition worsens.

“I don’t know how much more I can take,” says Morrill, who worked for 17 years as a housekeeper at Grace Hospital and is now retired. “It’s upsetting because I’d like to get it done and carry on with my life and go places and see things. I have two nieces in B.C. I’d like to visit; I have family in Quebec I’d like to see, but I can’t get on a plane because I can’t walk.”

Winnipegger Randy Marchinko has been waiting two years for hip surgery. The pain in his hips, both of which have to be replaced, has been getting worse in recent years. It’s limiting his mobility and making it increasingly difficult to perform physical tasks he used to do with ease, such as home renovations. The retired art teacher, 72, still likes to turn pottery. But even that is getting difficult to do.

“In the last six months, this has worsened considerably,” he says. “It’s pretty severe.”

After a consultation with his surgeon at Concordia Hospital in January 2021, he was told he would be able to get his first hip replaced in January 2022. The timeline gave him hope; relief was within reach.

As the year went on and the pain worsened, Marchinko grew concerned when no one contacted him about his surgery. He expected a call towards the end of 2021 to confirm his January booking. When he called the surgeon’s office, the response he got was devastating: his procedure was pushed back to late 2022.

Marchinko was given no date, not even an approximate month he could mark on his calendar. It’s as if he wasn’t even on a real waiting list. He was shocked and massively disappointed. Depression began creeping in.

“As the pain gets worse you get ticked off,” he says, adding even the simplest tasks, like getting out of his of car and walking to a store, is agonizing. “You want to get on with things and you can’t.”

The uncertainty around when Marchinko would get his surgery was crushing his spirits. Given the long wait times for orthopedic surgery in Manitoba and the backlog of procedures that piled up during the COVID-19 pandemic, when thousands of surgeries were cancelled, Marchinko had no idea when he would see the inside of an operating room.

“I don’t know what their caseload is, I don’t know the ins and outs of it,” he says, adding he didn’t know where he stood on the wait list. “It’s really confusing to me why there can’t be more specificity.”

Finally, a breakthrough: Marchinko received a letter June 10 informing him his first surgery date is set for Aug. 29, more than two years after his doctor said he needed surgery. Hope has been renewed — as long as the date doesn’t get pushed back again.

● ● ●

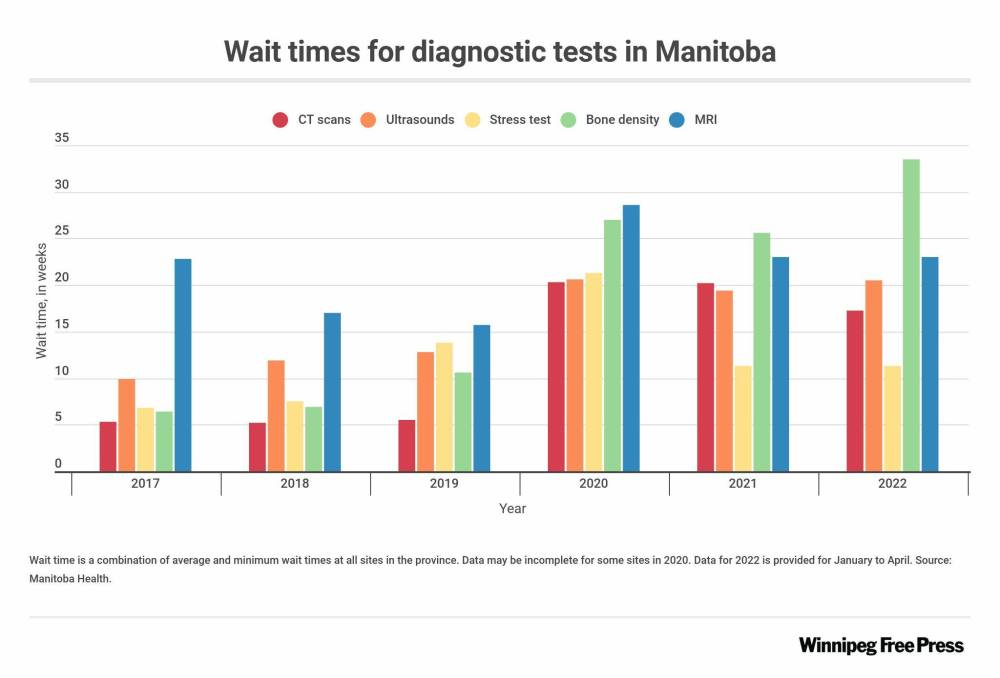

According to Doctors Manitoba, which represents more than 4,000 physicians across the province, the estimated backlog for a wide range of surgical, diagnostic and other procedures in Manitoba was 166,903 cases for the months of March and April. The backlog was driven largely by the pandemic, as hundreds of hospital staff over the past two years were redeployed to treat COVID-19 patients.

The provincial government has not released its own backlog estimates, nor has it established timelines or targets on how long it will take to clear them. The number of surgeries and diagnostic tests performed have returned to pre-pandemic levels in some areas. But in others, volumes are still below what they were prior to Manitoba’s first case of COVID-19 in March 2020.

Doctors Manitoba has been calling on the provincial government for more than a year to publish more up-to-date wait time data, as well as specific targets, so the public can see when wait times are expected to fall.

“Without this accurate, real-time data, it’s really hard to know if we do have the capacity (to reduce wait times),” says Dr. Kristjan Thompson, past president and current board chair of Doctors Manitoba. “I think they (the public) deserve to know how capacity is being built and with the capacity we have, how long their waits are going to be.”

“Without this accurate, real-time data, it’s really hard to know if we do have the capacity (to reduce wait times).”–Dr. Kristjan Thompson

There is some relief on the way for orthopedic surgery. However, it’s not expected to arrive until next year. The province’s diagnostic and surgical recovery task force, struck by Manitoba’s Progressive Conservative government last December, announced in March a plan to add a fifth operating room at Concordia Hospital, to boost capacity by up to 1,000 procedures a year — a 20-per cent increase provincewide over pre-pandemic levels.

The plan includes hiring an additional orthopedic surgeon and more staff. However, some of that new capacity — possibly all of it — will be absorbed by growing demand for hip and knee surgeries, driven largely by an aging population.

According to a wait-time task force commissioned by the Tory government in 2016, the demand for hip and knee surgery is growing by about five per cent a year. It recommended in its 2017 report that the province increase hip and knee surgical capacity by 900 procedures a year. That was the estimate needed to bring wait times down to national standards by 2021-22. The province more than achieved that goal. In fact, it surpassed it in less time than recommended. It did so partly through increased funding, but also by finding efficiencies, including shorter hospital stays.

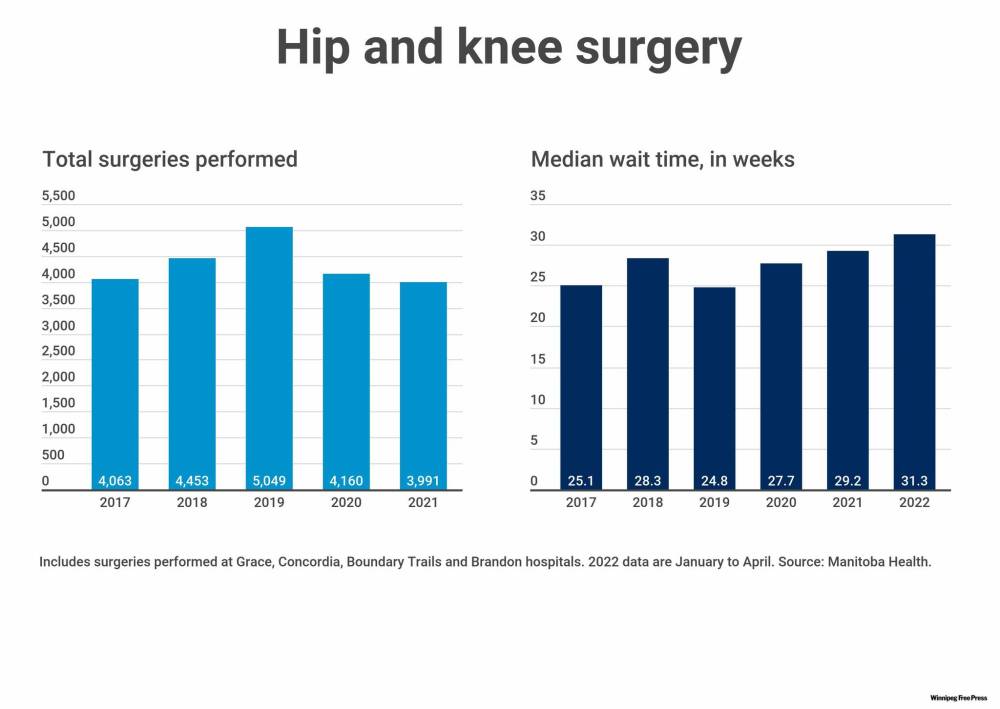

Manitoba performed 4,063 hip and knee surgeries, including revisions, in 2017, according to five years of detailed wait time and surgical data obtained by the Free Press. That grew to 5,049 by 2019, exceeding the goal of 900 additional surgeries per year. It had little immediate impact on wait times, as demand for orthopedic surgery continued to grow. However, it was starting to move the needle in the right direction. Median wait times in 2019 dipped to 24.8 weeks in 2019 from 25.1 weeks in 2017.

And then the pandemic hit.

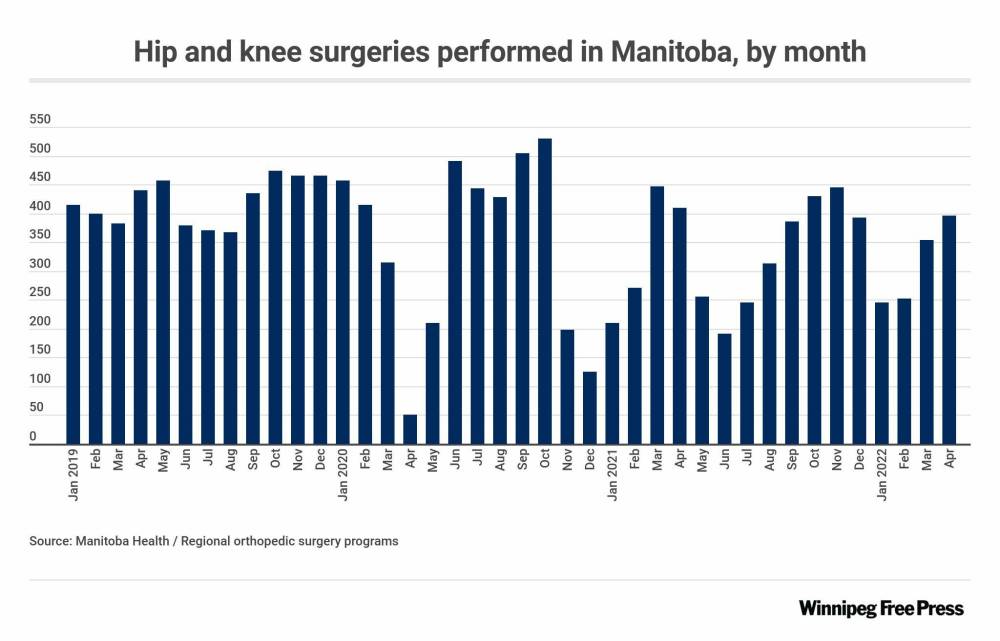

Whatever gains were made on surgical volumes between 2017 and 2020 were wiped out almost overnight because of COVID-19. Monthly data from 2020 shows the number of hip and knee surgeries plummeted from more than 400 procedures a month to only 50 in April 2020, as hospitals began shutting down operating rooms.

Surgical volumes rebounded by summer, but fell dramatically again by the end of the year when the second wave of the pandemic ripped through Manitoba, killing more than 600 people in two months and forcing hospital officials to cancel surgeries again. Hundreds of surgical staff were redeployed to medical wards to treat COVID-19 patients. Only 125 hip and knee surgeries were performed in December of that year, less than a third of normal volumes.

The cancellations, which continued in 2021 during the third wave of the pandemic, created a significant backlog, not only for orthopedic surgery, but for many other procedures, including diagnostic tests, such as MRIs and CT scans. The backlog for hip and knee surgeries grew by at least 2,000 cases between 2020 and 2021, given the rising demand for orthopedic surgery. Even as surgical capacity returns to pre-pandemic levels, the current volume of surgeries is doing little to reduce the backlog.

Doctors Manitoba estimates the backlog for hip and knee surgery was 2,402 cases in March, up from 2,372 in February. The number of hip and knee procedures performed in April (the most recent data available from Manitoba Health) was 396, up slightly from the previous month, but less than the 406 surgeries performed in April 2021. That’s an annual rate of 4,752, still below levels reached prior to the pandemic.

Even if the Manitoba government makes good on its pledge to add surgical capacity at Concordia Hospital, it will have no impact on wait times until 2023 at the earliest. The additional operating room is not scheduled to begin surgeries until next year. It was originally slated to open by the end of 2022, but has been delayed.

Delay equals deterioration

Posted:

The longer people wait for medically necessary procedures such as surgery and diagnostic tests, the worse their conditions usually get. They tend to become sicker and often suffer from increased bouts of anxiety and emotional stress. Eventually, many end up at the emergency department because they can no longer stand the pain and anguish.

“It’s difficult at this stage to pin down the date, the month, as a result of supply chain issues and disruptions and construction and timelines,” Manitoba Health Minister Audrey Gordon told a legislative committee May 20. “It’s not always in the hands of the project team, but we are aiming for 2023 and know that it will be operational and that members of the public will be able to get their hips and knee surgeries.”

If the 2017 task force report’s projections are accurate and demand for hip and knee surgery is growing by about five per cent a year (capacity would need to grow by some 250 to 300 surgeries each year), an additional 1,000 surgeries in 2023 would do little, if anything, to reduce the pandemic backlog. There were 5,049 hip and knee surgeries performed in 2019. A five per cent annual increase over four years would require 6,137 procedures by 2023 to keep pace with demand. An additional 1,000 surgeries per year would come close to covering that, but there would be no extra capacity to clear the backlog.

Some efforts have been made to increase surgical slates during the summer months throughout the province (the number of surgeries usually falls in July and August as staff take vacation). However, no estimates have been released by the province on how many more surgeries are expected to be performed during that period, or even for 2022.

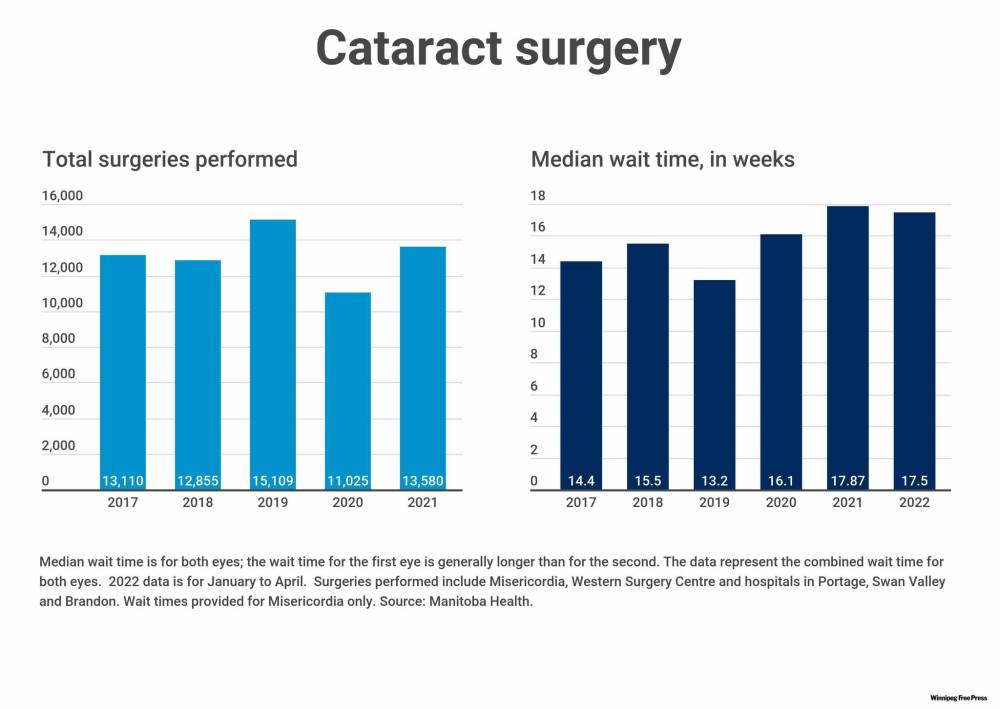

The situation is similar for other procedures, including cataract surgeries. The province increased the number of cataract surgeries (a procedure that includes implanting an artificial lens in the eye to correct vision loss) from 13,110 procedures in 2017 to 15,109 in 2019.

Increasing cataract surgeries by 2,000 procedures per year was one of the recommendations in the 2017 task force report. Like most other surgeries, the volume of cataract procedures fell dramatically during the pandemic and is only now returning to pre-pandemic levels. As a result, the province is scrambling to figure out how to reduce a backlog that is likely well over 5,000 procedures.

The province doesn’t publish provincewide wait times for cataract surgery, but does so for each of the six facilities in Manitoba where cataract procedures are performed. At Misericordia Health Centre, which does the most cataract surgeries of any health facility in Manitoba, the median wait time for surgery fell from 14.4 to 13.2 weeks from 2017 to 2019. It rose again to just over 17 weeks during the pandemic, after thousands of surgeries were cancelled. The monthly wait time in 2022 so far is 17.5 weeks.

The true wait time is longer. The way Manitoba Health calculates wait times for cataract surgery makes it appear shorter than it really is. The time it takes to get surgery on the first eye is usually longer than the second. It may take months or a year (or longer) to get cataract surgery on the first eye. However, the second eye is normally done within one to four weeks.

Instead of reporting how long it takes for the first eye, Manitoba Health reports the average for both eyes combined. It doesn’t capture the true length of time Manitobans are waiting for cataract surgery. If someone waited a year for the first eye and had the second eye done a week later, the wait time would be reported as six months.

According to the Eye Physicians and Surgeons of Manitoba, an independent advocacy group that represents ophthalmologists, the median wait time for the first eye in April at Misericordia was 29 weeks. However, the wait to see an ophthalmologist to determine whether a patient is a candidate for cataract surgery is 14.5 months.

That number is based on clearance reports from all ophthalmologists working in Winnipeg, whether they are doing surgery through private or public facilities, according to EPSM. As a result, patients are waiting close to two years on average for cataract surgery.

The wait to see an ophthalmologist to determine whether a patient is a candidate for cataract surgery is 14.5 months.

Dr. Jennifer Rahman, EPSM president and an ophthalmologist who performs cataract and glaucoma surgeries at Misericordia Health Centre, said the longer patients wait for cataract surgery, the more complicated their procedures can become.

Cataracts hang from fibres inside the eye. The longer the delay in getting surgery, the greater the chance those fibres can break loose from heavy and dense cataracts, she said. That can cause complications during surgery, resulting in longer recovery times and possible follow-up surgery.

“It’s more difficult to take out a late-stage cataract safely and it requires more time and effort,” said Rahman.

Long wait times for cataract implants also affect patients in other ways, she said.

“If they have poor vision, they may lose their (driver’s) licence, they may be unable to work or they may have difficulty with depth perception and be more at risk for falls, and then sustain an injury from falls.” – Dr. Jennifer Rahman

“If they have poor vision, they may lose their (driver’s) licence, they may be unable to work or they may have difficulty with depth perception and be more at risk for falls, and then sustain an injury from falls,” she said. Some patients’ vision is so poor while waiting for cataract surgery, they’re close to going blind, she said.

Once doctors determine a patient needs cataract surgery, it should be done within the national benchmark of 16 weeks, said Rahman. Manitoba is nowhere near meeting that target. Instead, cataract surgeries are often characterized as “elective”and don’t always get the urgent attention they deserve, she said.

“Once we put somebody on the list, we’ve acknowledged that this person has a visually symptomatic cataract,” said Rahman. “We’re not putting people on the list that don’t need surgery.”

The growth in health-care wait times is not unique to Manitoba. All parts of of Canada have experienced similar challenges. However, Manitoba has longer wait times than most other provinces, according to recent data from the Canadian Institute for Health Information. CIHI data for 2021 released in May show Manitoba was well below the national average in meeting benchmarks for procedures such as cataract and hip and knee surgeries, as well as for diagnostic testing, including MRIs and CT scans.

One of the key factors driving long wait times is a lack of centralized wait lists, including system-wide intake, said Dr. Michael Rachlis, a health policy consultant who co-chaired Manitoba’s 2017 wait time task force. While Manitoba has made some progress in that area, primarily in orthopedics, most specialists and surgeons still operate on their own, outside of a centralized model, he said.

That makes it difficult for patients to navigate the system, leaving many in the dark about when they can expect surgery, or other interventions. It also causes some to wait longer than necessary because they may be unaware of shorter wait times elsewhere, either with a different specialist or at another facility, he said.

Manitobans open to private help to clear backlogs: poll

Posted:

Nearly three-quarters of Manitobans think it’s a good idea for government to contract out more surgical and other medical procedures to private clinics to help clear the backlog created during the COVID-19 pandemic.

For example, the wait time for bone density tests (which measure bone strength) at St. Boniface Hospital in April was 36 weeks. At Brandon Regional Health Centre it was only eight weeks. Given the option, some patients may choose to travel for quicker service. However, if they’re unaware of that option, they may wait longer than they need to, even though Brandon has excess capacity.

“The system needs to be a whole lot more patient-friendly,” said Rachlis, a former Manitoban now based in Toronto. “We found lots of examples of where people had no idea that they could go to a central referral for hip and knee instead of just going to an individual surgeon who had a long list.”

One of the task force’s key recommendations was to develop central intake systems where people could get information about wait times, including a phone number to call where trained staff could help patients navigate the system. That recommendation was not acted on. As a result, patients often have an easier time tracking a parcel through a courier service than they do trying to figure out where they are on a health-care wait list, said Rachlis.

“If I were a politician, that’s the first part of the system I would work on changing,” he said. “Consumers deserve so much better.”

tom.brodbeck@freepress.mb.ca

Tom has been covering Manitoba politics since the early 1990s and joined the Winnipeg Free Press news team in 2019.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.