Beyond words Immersive Ojibwa language camp all about sustaining culture, fostering understanding and connection

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 03/06/2022 (1284 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

On a breezy May afternoon, on a tree-lined drive that curves through the front gate of Camp Manitou, Nova Courchene steps to a spot on the ground, like a batter walking up to the plate. The small crowd gathered around her offers a smatter of cheers and encouraging words, as Courchene stands ready for whatever is coming her way.

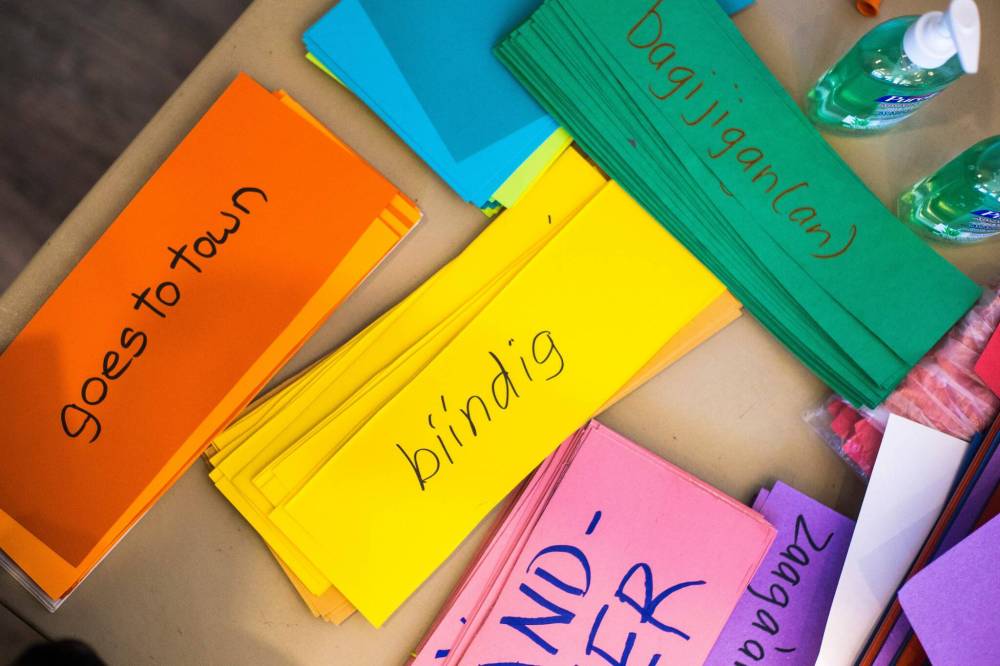

A short distance away, Noah Malazdrewicz stands with his back towards Courchene, rustling through a stack of flashcards in his hands. He pulls a card to the front and spins to face her, like a pitcher hurling a strike, but what he’s tossing is just words. He holds the card out to show what is written: a phrase in Anishinaabemowin, the Ojibwa language.

Aandi eyaayeg? Where are you guys?

Slowly, Courchene sounds out the words, letting the meaning connect on her tongue. Her lips move silently as she points her index finger at the ground, lost in the new maze the language has built in her mind. When she came to this camp, the first of its kind in Manitoba, she knew only about 20 Ojibwa words; yet for nearly four weeks, she’s used almost no English at all.

So what will she say now? Hesitantly, Courchene begins to form a word, one syllable at a time.

“Odominawak?” she says, with a quizzical rising inflection. We are playing. A right answer, but to the wrong question.

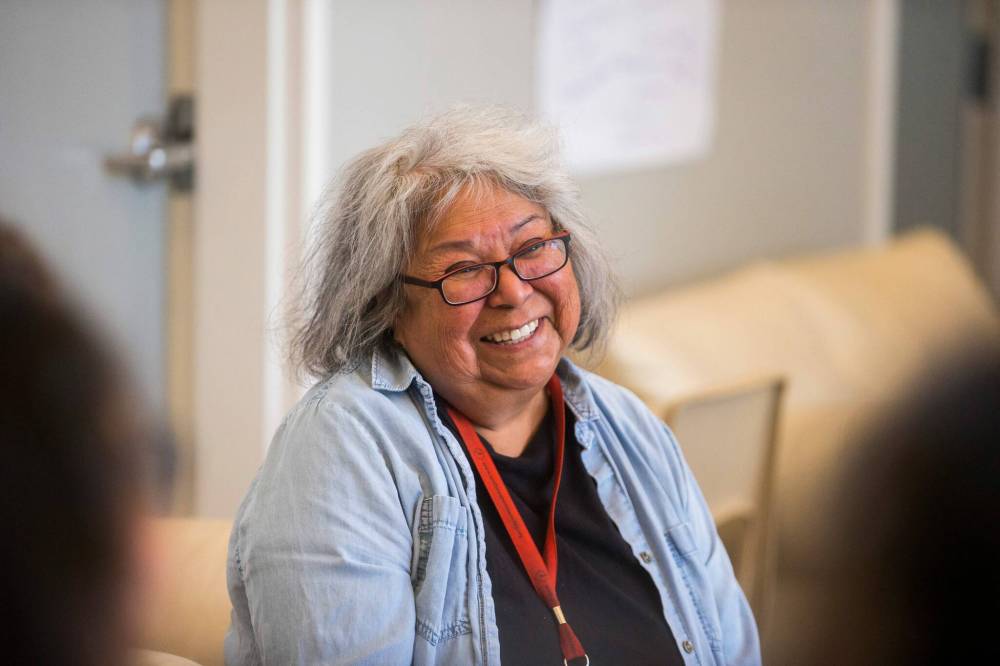

From a picnic table nearby, Patricia Ningewance shakes her head, and repeats the card’s phrase: “aandi eyaayeg,” she says, patiently. Courchene goes back into her mind again, and Ningewance, who has taught Ojibwa for over 40 years, smiles as she observes how determined Courchene is to glean the question and pluck the right response from her head.

“This student, she had nothing three, four weeks ago,” Ningewance whispers. “Now she can speak.”

This game, the baseball game, came to Ningewance one night when she was lying awake. That’s what language teachers do, she says: they’re always trying to think of new activities to get students talking to each other and learning grammar in “non-painful ways.” So why not have them toss out Anishinaabemowin questions, and take a swing at the answers?

“Sure enough, it worked perfectly,” she says.

For Ningewance, this camp, a pilot program which kicked off on May 4, is special. A University of Manitoba professor, she’s taught immersion camps before, but those usually lasted just one or two weeks. It’s not enough, she thinks. A fortnight only leaves students thirsting for more; so to offer nearly a month in Anishinaabemowin is “very long overdue.”

Soon, organizers hope, this format will play a key part in the revitalization of Indigenous languages in Manitoba. Because while there are thousands of fluent speakers in the province, the generational divide is wide: in many First Nations, most speakers are over age 60. Interest among youth is growing, but there aren’t enough teachers to help them.

To create more teachers, you have to build more speakers. And to do that, you need places to spend time in the language.

“It’s a really good way to bring that to the forefront, and really be proud of that, and use it and get it going,” camp facilitator Carol Beaulieu says, chatting one recent afternoon in the sunny office of a Camp Manitou building. “I’d like to see it before I die that I could go somewhere and hear somebody talking Ojibwa. Even if I was just in Walmart, or wherever.”

So this is a start, bringing learners here for a month together. What makes it more remarkable is that it all came together so quickly. The idea had been simmering, a joint effort between Indigenous Languages of Manitoba and the Anish Corporation, a non-profit focused on supports for residential school survivors. But they were waiting to secure funding.

In early April, organizers got the call: the funding was ready. Within a month they had secured some of the province’s most respected Anishinaabemowin instructors, including Ningewance, Roger Roulette and Dennis Chartrand, and planned four weeks of linguistic and cultural adventures. Now, they just needed to fill those weeks with campers.

Despite the short notice, interest in the camp was immense. Organizers received 44 applications, from which they had to select just a dozen participants; they wanted to keep the size small to encourage a more family-like atmosphere, and help campers get to know each other. Otherwise, Beaulieu says, it would become a bit too much like a classroom.

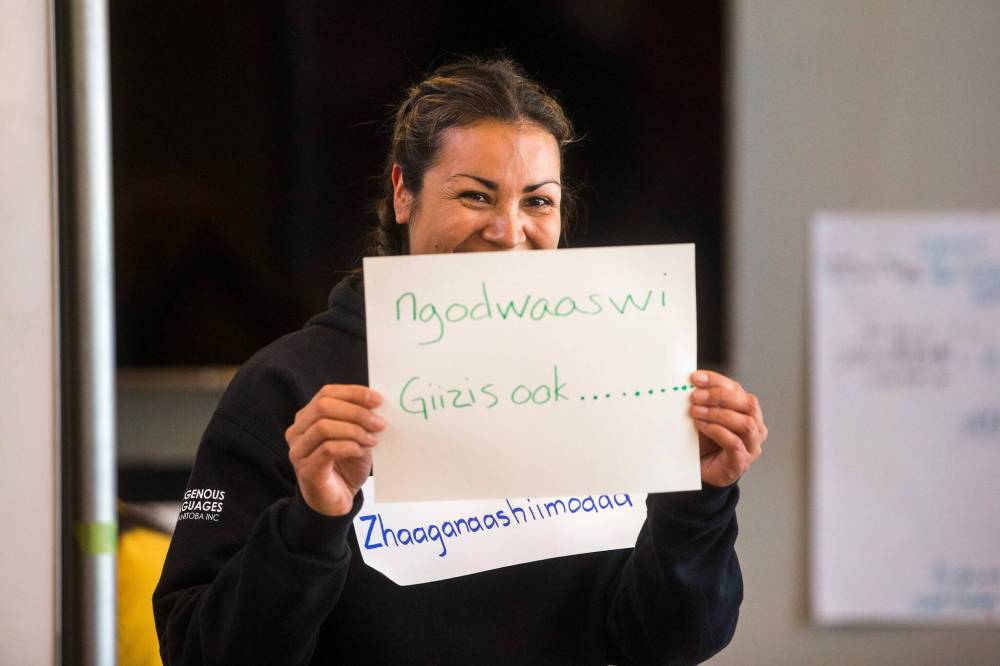

The first rule of the camp is simple: for four weeks, campers must live and play almost entirely in Anishinaabemowin. On the door of Beaulieu’s office is a note that says omaa eta zhi-zhaaganaashiimoyan: “you can only speak English here.” Outside of that room, participants were expected to stay in the language the whole time.

One thing organizers hoped to learn, from this first edition, was what type of students would thrive in that environment. The camp is geared towards intermediate speakers, but the participants chosen spanned all ages and all ranges of familiarity with the language. Some had been to immersion camps before; others were taking their first steps in formal learning.

Each had their own reason drawing them to spend a month in Anishinaabemowin.

Malazdrewicz is the lone non-Indigenous student; he works at the Manitoba Indigenous Cultural Education Centre, as does another camper. Dené Sinclair, who also does contract work at the MICEC, had spent much of the pandemic taking Ojibwa lessons via Zoom, hoping to better understand elders speaking in their own language.

Naomi Fosseneuve, a member of Long Plain First Nation, wanted to do the camp for her four children, the eldest of which is 22. When her kids came to visit one weekend, she took them for a walk around the camp’s duck pond and spoke to them only in Anishinaabemowin. Her kids were so excited, she says with a laugh, they actually applauded.

“When we got to the car, I was like, ‘I’m going to teach all of that to you,’” she says.

For one of the campers, the language part came easy. A fluent speaker, Evelyn Kennedy had grown up with Ojibwa and had worked on language programs in her community of Hollow Water First Nation, about 200 kilometres north of Winnipeg. Still, she’d wanted to learn more, because when it comes to any language, there are always deeper levels to discover.

At first, she was nervous about camp — “I thought, ‘oh, they’ll probably speak better than me,’” she says, with a laugh — but instead found herself being able to help the others. Sinclair, who was her roommate at camp, says that Kennedy came with a natural teaching and caregiving spirit the rest of the campers found invaluable.

“Not only is she a fluent speaker, but she’s such a positive and supportive and loving person, so it was those two things put together,” Sinclair says. “One part of learning the language is we all really want each other to succeed, because it makes our language journeys stronger… She was there as a support and teacher for all of us, and I think that’s just Evelyn.”

Yet Kennedy found the camp challenging for reasons beyond words. Four weeks is the longest she’s ever been away from her family, including the two young grandchildren she and her husband are raising. Usually, she’s with the kids “24-7,” she says, and in the early days she missed them so much that she thought about leaving.

But she stuck it out was glad she did. She had “so many firsts” at camp, she says: her first sweat lodge ceremony. Her first visit to the Manito-Ahbee Festival, which was the largest powwow she’d ever seen. When she started to miss her family too much, the other campers helped lift her up, and that eased the ache enough to keep going.

“To me it feels like we are family already, so I’m going to be sad when I go home,” she says. “I’m probably going to cry on my last day. I’ve gotten to know everyone here. It’s been wonderful. So I don’t want it to end, but at the same time you’re missing home.”

Of the group, Courchene, 37, may have come in with the least knowledge. A member of Sagkeeng First Nation, she hadn’t grown up with Anishinaabemowin. Her mother had, but as a girl her mother had been taken from her family and adopted out to a non-Indigenous home, caught by the ’60s Scoop that severed so many ties to culture and tongue.

Courchene, at least, had grown up a bit more connected. When she was child, her mother got a teaching job on a Blackfoot First Nation in Alberta; as a teen, she danced on the powwow trail out west. At 21, she moved to Toronto for school, where she joined an Indigenous theatre troupe and met friends from the Dakota, Oneida and Mohawk nations.

As the years turned, she found herself wanting to deepen her connection to language and culture. She works in resource development for the Frontier School Division’s Indigenous Way of Life division, where she designs graphics for Cree and Ojibwa teaching materials; she also runs Native Youth Theatre, a part-time program offering free acting classes.

Doing that work left her feeling it was time to reconnect. The idea of a month-long Ojibwa immersion camp was scary at first, especially as she had so little understanding of the language; but no time like the present to get started, she thought.

“That’s how I learn,” she says, with a laugh. “I throw myself in.”

Sometimes it felt like she was drowning, especially at the beginning, when she found herself submerged by a deluge of words and grammar, trying to divine meaning from actions. But one day in the second week, she realized with a jolt that she could understand the commands teachers gave without too much effort. Gaawiin: no. Miinawaa doodan: do it again.

That’s when she felt like she was starting to tread water, she says, and then there were even moments where she was able to swim, following the current of the language instead of being pulled beneath its surface. Bit by bit, phrases started to tumble off her tongue, and those 20 Ojibwa words she brought into camp became dozens, then hundreds.

One night, she was lying awake in bed, frustrated that she couldn’t remember the verb for “fighting.” Then a memory came to her, of the other campers joking about about wanting to fight a makwa, a bear. In her mind, she could see them making playful fists. She could hear their radiant laughter, a sound that had echoed through camp since it started, and then…

Miigaazo, she thought, with a surge of elation. Miigaazo. A person is fighting.

“My brain is processing, and I can’t even tell it’s processing,” she says. “You just have to take a backseat and be like, ‘ah, my brain actually has this, don’t be too hard on yourself.’ Your brain takes that time to process that amount of information.”

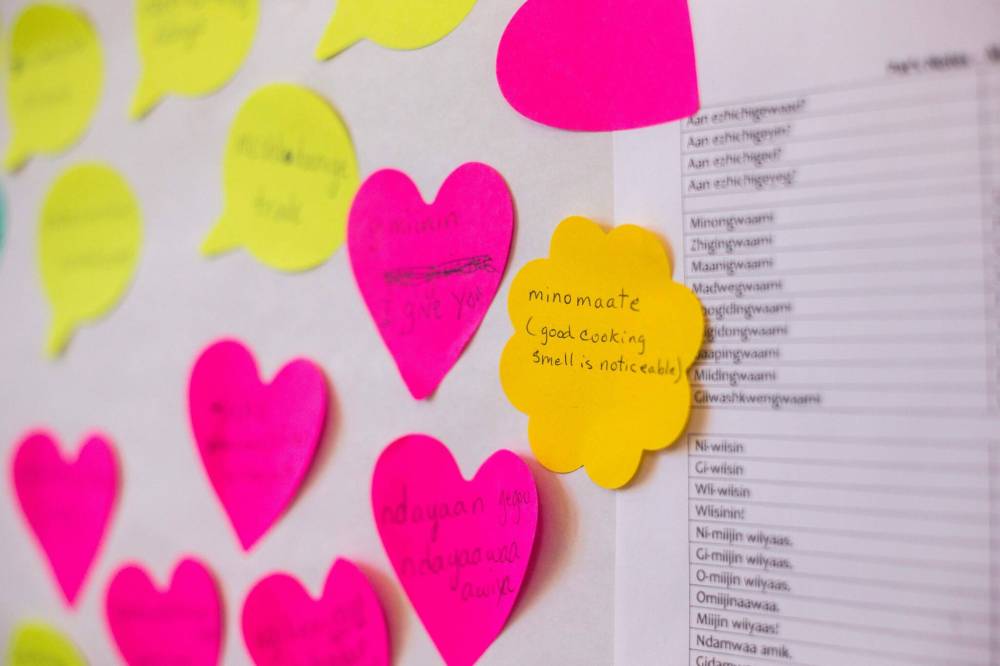

What Courchene discovered then is what Ningewance has learned through long experience: that language is learned most of all in the using. Books and resources are important — Ningewance has written several, including a popular textbook, Talking Gookom’s Language — but to really acquire a language, it has to come alive in your everyday life.

Ningewance structured the camp’s lessons with this in mind. Once, she says, she used to start courses by teaching Ojibwa’s verbs. It’s a traditional way of teaching most languages, relying on rote memorization, pretty dry. But these days she focuses on starting with phrases of connection, words that learners can employ as soon as they grasp them.

“I want students to learn to communicate with each other,” she says. “Basic needs, things they can use in a meaningful way from day one. ‘What are you doing? Where are you going? What did you do yesterday?’ Then it’s more useful, they’re more motivated to learn. They can talk to each other. They’re curious about each other.”

This approach works. On one of the first days at camp, Fosseneuve and another camper, Gina Mount, went for a walk and tried to stay in the language as they pointed at the things they saw, the geese and the trees and the weather; their attempts were so fragmented, and so riddled with mistakes, that they spent most of that walk just laughing at each other.

But just a few weeks later, they went for a walk again, and this time their speech flowed comfortably.

“It was incredible,” Fosseneuve says, of that moment. “I was like ‘ahh, it’s happening!’ It’s working. The camps work.”

The joy the campers found in that process — including, and even especially, in the mistakes — is critical to the success of a camp like this, in more than one way. Partly, it served as an antidote to frustration; but most of all, it acted as a balance to the difficult internal journeys many Indigenous speakers must take, when working to reclaim their language.

“It feels like a lot of pressure,” Courchene says. “It’s a really hard thing to explain how special it feels… Knowing that as an Indigenous person today who’s trying to take it back, you’re taking it back for your grandparents who lost it or who weren’t allowed to speak it for their kids. Or who didn’t make it back home, and can’t teach their grandkids.

“That’s a heavy load. I know everyone in the camp felt that, or acquires it as new speakers.”

Ningewance knows this too. Through her years of teaching, she’s noticed it’s often a little easier for non-Indigenous students; they don’t carry the “emotional baggage” that generations of colonial assaults on Indigenous culture left on the communities. Indigenous students, she thinks, tend to feel more pressure to grasp the language right away.

In many cases, she adds, this is a deeply emotional experience. Learners may be the first member of their family to speak the language in decades; so even just by deciding to learn, they have to negotiate a knowledge of colonial damage. Next year, she wants to hold a conference for teachers, to examine how to guide students through what she calls these mental blocks.

“It’s caused by traumas,” she says. “Especially what were endured in residential schools. And the perception that Native languages are second-best, there’s a lot of that feeling around. It’s everywhere. You go to a meeting, and everything is in English. Nothing is first in Ojibwa anymore. It’s just what we live with, and it trickles down to the classrooms.”

The key to getting past that, she thinks, is making the learning fun. It’s important that the students be able to laugh, because it’s the laughing that makes the mistakes less scary, and mistakes are a key part of teaching the brain how to organize itself in a new tongue. And if errors need to be made exuberantly and often, they at least ought to be entertaining.

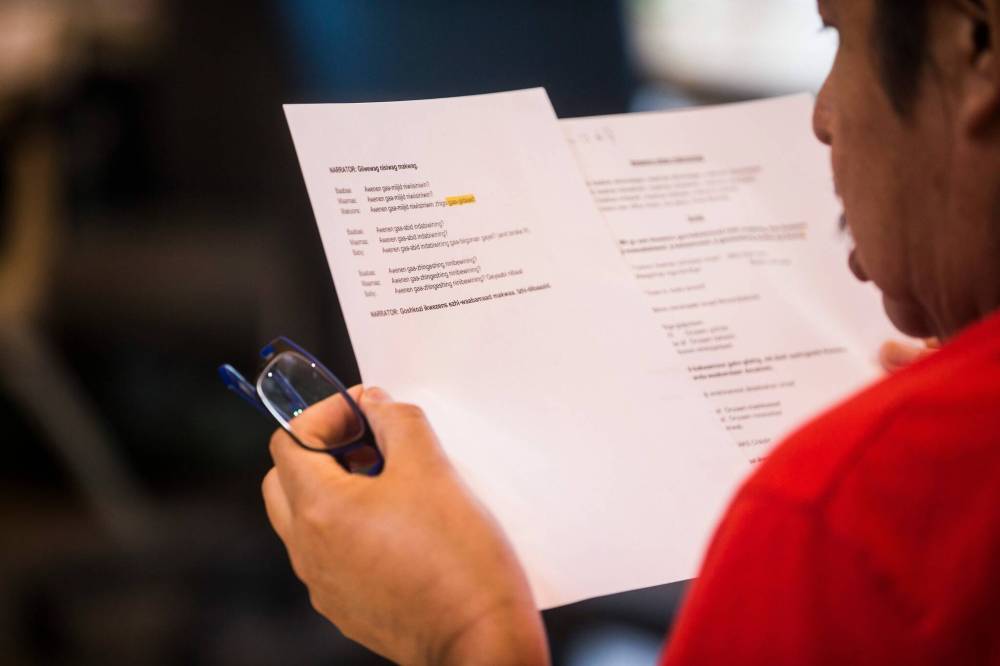

So laughter, that’s the operating sound of the camp. It is electric, infectious and joyful. It bounces off the walls of the main building, where they hold most of the day’s lessons; it erupts when they act out skits they’ve written in Anishinaabemowin, or don silly masks to role-play as animals or outlandish characters.

The best part, Ningewance says, is that the humour comes right from the language. It came, for instance, when a camper tried to ask a fluent speaker about his evening, but mixed up one letter of a word and asked about an, ahem, private body part instead. Stories like that happened a lot; campers often caught instructors smothering laughter.

“There was a time I was trying to say a word,” Courchene recalls. “I kept stumbling over it and re-trying it, and re-trying it, I could see (instructor Roger Roulette) giggling in the corner and I was like, ‘oh, I’m probably saying a really dirty word.’”

Now, organizers are planning to take what they learned from this camp and carry it forward to other editions. There will be similar camps for Cree, for Oji-Cree, for Dakota. The plan, Beaulieu says, is to operate each on a regular annual schedule, so that people can plan well in advance. Someday, she hopes, campers will come back to help out the programs.

‘It’s very rewarding. You’re just happy hearing them saying the words, getting the words out of their mouth when the first week they had such trouble. It’s very gratifying.’– Patricia Ningewance

And in time, maybe that cycle will produce a new generation of speakers, who can take their skill into an education system that, right now, lacks enough teachers to reach every student. Someday, Beaulieu envisions a Manitoba where every school that wants it can have Indigenous language classes, or even immersion. For those youth, it does matter.

“People are realizing that it is something that is needed for some sort of stability, because the accurate cultural information is in the language,” Beaulieu says. “Once you have that knowledge, then you know who you are. You know where you come from. You understand the worldviews a little bit better.”

Once, years ago, maybe there wasn’t so much focus on language as is emerging now, she says. For Beaulieu, who has worked with language revitalization since 1994, it was a “frustrating ride.” Back then, there seemed to be an attitude that Manitoba had plenty of fluent speakers, so there was little fear of them disappearing; but the generational gap was growing.

So right now marks a golden opportunity, a critical window of time to secure and then invigorate language transmission. Ningewance would love to someday see dedicated full-time spaces, where people can come and speak or just live in their languages; for now, she’s just glad to see how every student she teaches comes out a little more confident.

”It’s very rewarding,” she says. “You’re just happy hearing them saying the words, getting the words out of their mouth when the first week they had such trouble. It’s very gratifying. It makes you happy. Especially when their parents were forbidden to do so, and they have such joy doing so. You feel very useful, when you hear that.”

As for the campers, the ripples are already spreading. Courchene’s mother has started brushing up on Anishinaabemowin, her brother has taken a few classes, and her sister is thinking of doing the same. The hope, Courchene says, is that one day her family could speak it together, bringing it back to one of the homes from where it had been taken away.

But first, back to basics. Back to that breezy May afternoon at camp, where Courchene steps up to the imaginary plate for a second swing at the baseball game. Malazdrewicz spins to deliver another verbal pitch: “aan ekidod” or, to put it in English, “what is he or she saying?”

This time, Courchene does not hesitate. She calls out her response, loud and clear.

“Pat ikido boozhoo,” she replies, nodding at Ningewance: Pat is saying hello. All around her, the other campers burst into cheers. Courchene turns to face them as a grin breaks over her face, and gives them a big wave. “Boozhoo,” she calls again, hello, and for a minute, the only sounds that float through the trees are the peals of their laughter.

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.