Battered and burned out Manitoba public health inspector reflects on difficult two years during COVID enforcement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 23/02/2022 (1388 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

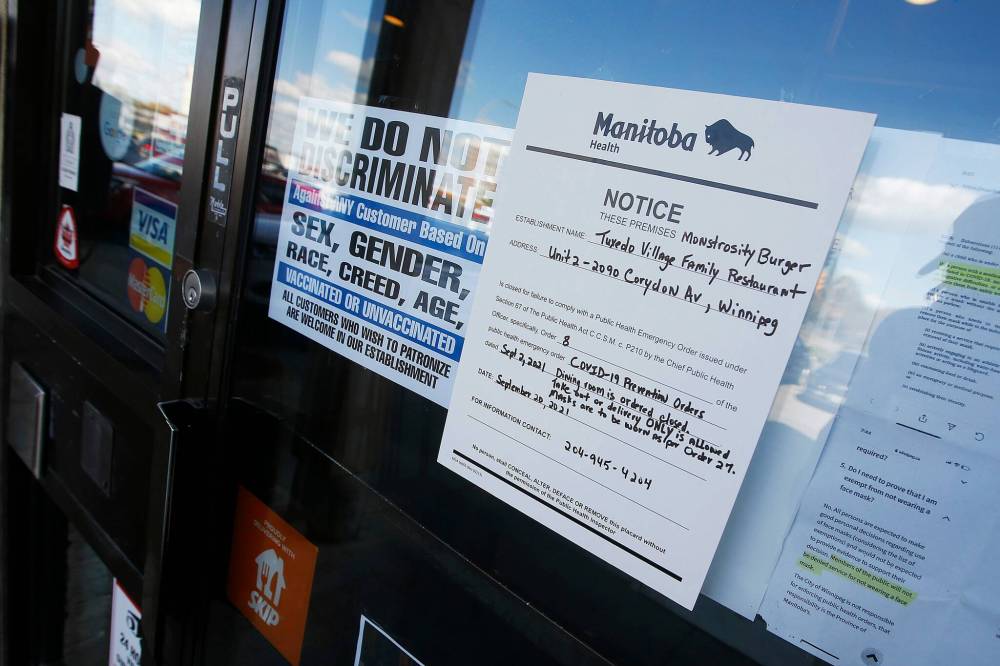

They’ve been shoved, swung at, racially abused, threatened and called Nazis or other names by strident opponents of Manitoba’s COVID-19 restrictions.

Provincial public health inspectors thrust onto the front line of pandemic education and enforcement efforts have suffered the brunt of fury triggered by government rules aimed at protecting Manitobans.

With restrictions set to be scrapped by mid-March, an inspector is reflecting on a two-year period in which she and her colleagues have faced an unprecedented workload and abuse never imagined.

“The profanities I have heard are unbelievable. Words hurt. It adds to the burnout we are already facing,” said the inspector, who agreed to speak on condition of anonymity. “(People) are so angry with you because you are the face of the government. A lot of it comes down to people not knowing the difference between rights and privileges.”

Inspectors have been tasked with making sure Manitobans wear masks, show proof of vaccination and self-isolate, among other rules, while putting themselves at potential exposure to the virus.

Volatile incidents are rare, the inspector said, but it leaves a mark when someone lashes out over a fine, an inspection or restrictions in general.

“The profanities I have heard are unbelievable. Words hurt. It adds to the burnout we are already facing.” – Inspector

“We enforce the law, but we don’t make the law,” said the inspector, who feels like she and her co-workers have become scapegoats. “Health inspectors are people. They have families and young kids.”

She described numerous incidents over the last two years where inspectors were assaulted, harassed or intimidated.

Someone took a swing at an inspector enforcing COVID rules in Winkler, she said. That city has seen some of the fiercest opposition to restrictions.

“There have been angry members of the public who have resorted to pushing and shoving. We’ve had a lot of situations where we’ve had to de-escalate or situations where we haven’t been able to de-escalate and have had to leave,” the inspector said.

Police are asked to join them on assignments considered potentially dangerous.

One such occasion was a visit to a Steinbach-area church to check if it was complying with limits on public gatherings.

Church members slammed their hands against a vehicle, yelled at inspectors and put cellphone cameras in their faces, the inspector said.

When cameras come out, video clips or photos usually end up on social media.

“There have been angry members of the public who have resorted to pushing and shoving. We’ve had a lot of situations where we’ve had to de-escalate or situations where we haven’t been able to de-escalate and have had to leave.” – Inspector

Inspectors have been locked out of businesses by owners who refuse to comply with rules. Their names and work phone numbers and addresses have been posted on social media by those opposing the restrictions.

“Some of them were blatant threats,” the inspector said.

Some are so worried about their safety they’ve gone to “extreme” lengths to protect themselves and their families.

This includes no longer driving their own vehicles to inspections considered high risk. Some have changed the address on their personal vehicle’s registration because they’re worried about being tracked.

The “toxic” environment has led some to find jobs in other jurisdictions or other work, the inspector said.

While trouble has occurred all over the province, those working in parts of the Southern Health region have faced more resistance than colleagues elsewhere in Manitoba, the inspector said.

“They face issues on a regular basis, if not a daily basis. These areas are constantly showing issues with compliance,” she said. “We have resorted to often having police attend with inspectors because situations become dangerous.”

The job has never been this demanding or heavy on enforcement, she said.

The inspector felt a sense of relief when Premier Heather Stefanson announced all restrictions, including face masks and proof-of-vaccination requirements, will end March 15.

With no pandemic rules to enforce, it means the inspector and her colleagues likely won’t face as much abuse.

“It’s a relief to not have to wonder if today I’m going to have a camera in my face or have someone yell at me,” the inspector said. “I get to go back to being a health inspector and doing the work I enjoy doing.”

COVID still poses a threat, she pointed out.

Since April 9, 2020, a total of 2,586 tickets have been handed out for public health order violations. They amount to more than $3.5 million in fines, according to the province’s online enforcement dashboard.

As their work moves away from COVID, inspectors will have to tackle a backlog of inspections put on the “backburner” during the pandemic.

Amid a number of vacancies, some districts do not have a public health inspector, she said, adding low pay has made it tougher to recruit and retain staff.

Manitoba offers one of the lowest annual salaries in Canada, starting at $50,744 and topping out at $67,671, according to industry data.

Inspectors in Saskatchewan are paid between $77,868 and $94,736, while those in Alberta earn $85,426 to $126,510.

“Prior to COVID, (inspectors) were there to make sure our restaurants were serving us safe food and the water we swam in at public pools was safe,” said Kyle Ross, president of the Manitoba Government and General Employees’ Union. “When COVID hit they were called upon to take on even more work, helping to enforce public health orders. They did this, and continue to do this, with mounting workloads and staff shortages.

“As we reopen, we need the government to address these issues and make the much-needed investments to help these inspectors do their jobs and keep Manitobans safe.” – Kyle Ross

“As we reopen, we need the government to address these issues and make the much-needed investments to help these inspectors do their jobs and keep Manitobans safe.”

The province did not provide comment by press time.

chris.kitching@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @chriskitching

As a general assignment reporter, Chris covers a little bit of everything for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.