Treaty 1 contentious from Day 1 Ottawa’s 1871 pact with First Nations built on bad faith, intimidation, impatience

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 30/07/2021 (1686 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

When Adams Archibald arrived in Manitoba in September 1870, tensions were running high in the two-month-old province.

It had already been a tumultuous year in the Red River settlement: Local Métis, led by Louis Riel, staged an armed uprising the previous winter and blocked Canada’s attempt to unilaterally take over what was then Rupert’s Land.

Upon Manitoba joining Confederation in July, troops, led by Col. Garnet Wolseley, landed in Winnipeg to secure the region. Meanwhile, there were growing strains between settlers and First Nations, who were eager to secure their own rights, much like the Métis had gained during their negotiations with the federal government.

Several Indigenous leaders, included Chief Henry Prince from St. Peter’s band, intercepted Archibald, the province’s newly appointed lieutenant-governor, at a place known as “Indian Mission” near the mouth of the Red River. They wanted to begin treaty talks with the Queen’s representative as soon as possible.

But after a 25-day arduous journey from Ottawa, Archibald was eager to settle into his new quarters in Winnipeg and insisted that talks would wait.

“The Indians in this neighbourhood are in a state of considerable excitement,” Archibald wrote to Joseph Howe, Canada’s secretary of state for the provinces. “They are very much demoralized by the transactions of the last few months. They do not seem to see why they should not have some share of property, which they know to be in the possession of people who are not its owners.”

While the Métis gained land concessions and the protection of their language and democratic rights — at least on paper — First Nations were left on the sidelines, even though they were the original inhabitants. They remained largely neutral during the resistance and were promised — it’s unclear by whom — they would be rewarded for their loyalty to the Crown during the “troubles” of 1869-70.

Archibald confirmed that in one of his letters to Ottawa shortly after his arrival.

Reconciliation hinges on honest analysis of Treaty 1

A red, pock-marked plaque displayed outside the entrance of Lower Fort Garry declares First Nations gave up their territory to allow for the peaceful settlement of the West.

Titled “Indian Treaty No. 1” and bearing Canada’s coat-of-arms, the weathered plaque was erected in 1928 by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada.

A red, pock-marked plaque displayed outside the entrance of Lower Fort Garry declares First Nations gave up their territory to allow for the peaceful settlement of the West.

Titled “Indian Treaty No. 1” and bearing Canada’s coat-of-arms, the weathered plaque was erected in 1928 by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada.

“In return for reserves and the promise of annuity payments, livestock and farming implements, the Indians ceded the land comprising the original province of Manitoba,” it reads.

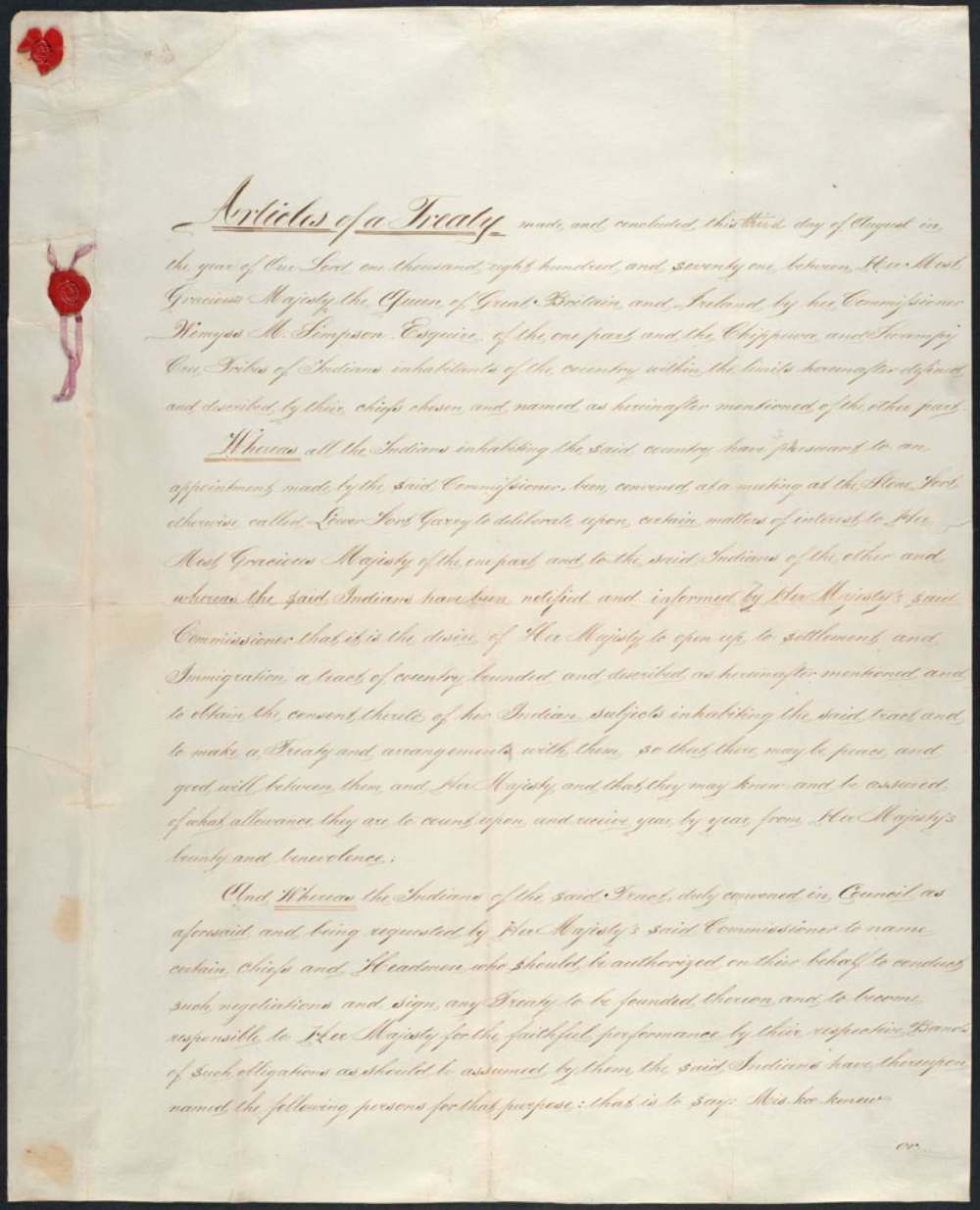

The plaque reflects the official written text of Treaty 1, namely that First Nations “do hereby cede, release, surrender and yield up to Her Majesty the Queen and successors forever all the lands included within the following limits,” the boundaries of which were roughly the size of the original 1870 “postage stamp” Manitoba.

The federal government considered Treaty 1, and all the numbered treaties negotiated thereafter, as formal agreements by First Nations to give up title to their land. Canada, under British law, purchased Rupert’s Land and the North-West Territories from the Hudson’s Bay Co. a year earlier and considered it Dominion property. As far as Ottawa was concerned, treaties were agreements within that legal framework.

But that’s not how First Nations viewed them. Indigenous leaders neither approved the HBC sale (they found out about it well after the deal was made) nor expressly agreed to surrender their land during treaty talks.

“That was never in the mindset of our people that they were going to surrender all this land, they looked at it from the point of view of sharing,” said Sagkeeng First Nation Elder Dave Courchene.

There is little historical evidence supporting Canada’s claim that Indigenous leaders agreed to cede or surrender their land. Senior government officials at the time, including Indian commissioner Wemyss Simpson, claim the chiefs (through interpreters) made that concession. But there are few, if any, records from independent sources to support that. Nowhere in the detailed newspaper accounts from The Manitoban (which both Simpson and lieutenant-governor Adams Archibald accepted as an accurate account of the deliberations) are there reports of chiefs agreeing to cede or surrender land.

There were discussions around the exclusive use by settlers of limited tracts of territory that would become off-limits to First Nations. But there were also documented promises made by Simpson and Archibald that vast tracts of land would remain unoccupied where Indigenous people could continue to hunt, fish and trap, as they always had.

“Till these lands are needed for use, you will be free to hunt over them, and make all the use of them which you have made in the past,” Archibald said. “But when lands are needed to be tilled or occupied, you must not go on them anymore. There will still be plenty of land that is neither tilled nor occupied, where you can go and roam and hunt as you have always done.”

The idea of land ownership, in the British common law sense, was foreign to First Nations. They lived off the land and had a spiritual relationship with it. But nobody owned it.

“The concept of owning the land was a ridiculous idea, that anyone could own the land,” said Courchene, founder of Turtle Lodge International Centre for Indigenous Education and Wellness. “Many of our elders say that, who would ever think that they could own the land?”

First Nations’ relationship with the land is not something that can be extinguished in a treaty, he said.

“Cede is not even in the vocabulary of our people simply because we don’t own the land,” said Treaty 1 Elder Florence Paynter of Sandy Bay First Nation. “We were placed here by the creator and our stories that are passed on to us from one generation to the next has always upheld that we will share.”

Paynter said her ancestors agreed to share the land with newcomers, not surrender or cede it.

“Why would our people give up the land when it’s not ours to give?”

It’s unclear, based on historical records, whether First Nations chiefs agreed to the written text of Treaty 1 or even saw its final version. Most didn’t speak English and both sides relied on interpreters during talks. There is little documentation of the proceedings beyond the detailed reporting in The Manitoban newspaper and from written correspondence between government officials. There is also oral history that has been passed down through generations of First Nations and retained by knowledge keepers.

“When our chiefs signed the documents, they were led to believe they were heard,” said Roseau River First Nation Elder Charlie Nelson. “They signed the document, but I don’t think a lot of them could read what they were signing.”

Historical records show many of the oral promises made during treaty talks were not included in the written text. Some were added four years later in what Ottawa called the “outside promises,” including a commitment to provide First Nations with farm implements. As part of the amendment to the treaty, the federal government raised the annuity to $5 per person from $3 “out of good feeling to the Indians and as a matter of benevolence,” the order-in-council that approved the changes says.

However, the grievances were only addressed after several years of lobbying by First Nations. Some chiefs refused to accept their annuities until the matter was resolved. The federal government described the omissions as a “misunderstanding.”

As part of the agreement, First Nations had to abandon any future claims to unfulfilled promises made by Ottawa, other than those agreed to in the 1875 addendum.

Arguably the most important promise – a solemn pledge that Indigenous people would be able to continue their way of life and would not be forced to “live like the white man” – was not only excluded from the written text of Treaty 1, the federal government violated it almost immediately.

Five years after the signing of Treaty 1, Ottawa passed the Indian Act. The legislation, which still exists today and has undergone many changes over the years, was the beginning of Ottawa’s persistent attempts to assimilate Indigenous people into white society, including the use of residential schools.

“Your ancestors and my ancestors went into an agreement that they would not interfere with anything that our people were doing, with the understanding that your people would be free to live,” said Elder Paynter. “Sure, we’ll share the land with you but let us… continue to hunt, trap and fish and just be who we are as a people.”

Instead, the federal government used the treaty as “an instrument of domination” through the Indian Act, said Elder Courchene.

“I think they forgot to add a word within that act,” he said. “They call it the Indian Act but what I call it is the Indian Domination Act.”

In order for true reconciliation to occur, the real story of Treaty 1, and all the numbered treaties, has to be better understood by Canadians, including how treaty commitments were ignored or broken, said Elder Nelson.

“We’re really a kind people and a sharing people but we have to tell the truth and we have to be strong about it,” he said. “We’ve got our backs against the wall and I think we need more understanding so we can help ourselves.”

Long Plain Chief Dennis Meeches, who also serves as Treaty One Nation spokesman, said the treaty relationship has been one-sided for most of the past 150 years. He said there’s positive momentum today to start repairing that relationship, including more education around what First Nations agreed to when they partnered with Canada.

“We’re not saying we want out of Canada, we’re part of Canada — that’s our history,” said Meeches. “But we want Canada also to recognize our sovereignty and our relationship with the land and the relationship to one another.”

That’s not just a job for Indigenous people, he said. It’s a responsibility all Canadians share. If successful, all Canadians will benefit, said Meeches.

“This might be a pivotal moment in our time, in our history, and hopefully we can truly begin that reconciliation.”

tom.brodbeck@freepress.mb.ca

“I have no doubt that, with a view to keep them quiet during the troubles, large promises were held out to them, having shown themselves ready to sustain the authority of the Crown, and having refrained from pillage and disorder, they feel that they have claims for consideration and remuneration. It is impossible not to admit that from their point of view, there is some justice in their claims.”

Indigenous leaders were also unhappy Rupert’s Land was sold from under them by the Hudson’s Bay Co. to Canada earlier that year. No one consulted them about the sale, a transaction many Indigenous leaders saw as illegitimate.

Archibald was given instructions by Ottawa to “establish friendly relations” with First Nations and determine how best, “whether by treaty or otherwise,” to clear the way for Europeans and Canadians to settle the West. The federal government, headed by prime minister John A. Macdonald, was not so much interested in ensuring the rights of Indigenous people were met as much as it was focused on avoiding violent conflict with them.

Archibald, a former Nova Scotia politician and a Father of Confederation, picked up on the political lay of the land quickly. After consulting with chiefs and other leaders in the community (including some with connections to the federal government, including Donald A. Smith who was sent by Ottawa months earlier to intervene in the Red River Resistance), Archibald was aware of the urgency around treaty talks.

However, he delayed negotiations until the following year, telling Prince and other chiefs he needed time to establish the new provincial government at Upper Fort Garry. He promised he would call for them for talks in the spring.

In the meantime, Archibald attempted to quell tensions between First Nations and non-Indigenous settlers around Indian Mission. Archibald was under pressure to encourage the bands to “disperse to their hunting grounds” in order, he wrote, to avoid “hostile collision between them and the people, which would have a very disastrous effect.”

The federal government, headed by prime minister John A. Macdonald, was not so much interested in ensuring the rights of Indigenous people were met as much as it was focused on avoiding violent conflict with them.

He provided the chiefs with ammunition and gun flints, a few bags of flour, tobacco and tea to encourage them to leave. He also used the fear of a smallpox outbreak in nearby Portage la Prairie as further inducement to relocate.

“The Indians are in great terror of this disease, which proves so fatal to persons of their race, and I am in hopes they will, for their own sake and for the sake of the neighbourhood, immediately disperse,” Archibald wrote.

Most did. They returned the following summer to negotiate the first in what would be several historic numbered treaties between Canada and First Nations — Treaty 1.

● ● ●

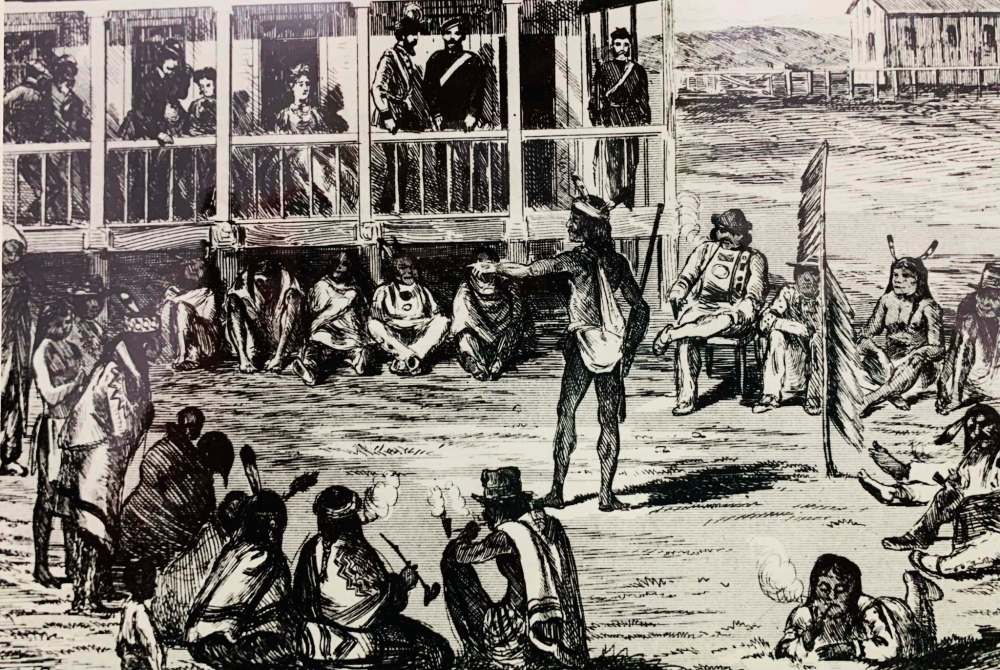

Hundreds of Anishinaabe and Swampy Cree poured into the grounds of Lower Fort Garry in late July 1871, many arriving on foot or horseback with their families, some from as far away as the United States border.

They set up birchbark lodges and tents outside the Hudson’s Bay trading post, located along the Red River, just north of Winnipeg. Women baked bread and made tea while children ran about. The sounds of chanting in a low tone and the hammering of a frying pan filled the air, signalling a game of gambling was about to begin. The encampment formed a semicircle outside the fort. In the middle, First Nations chiefs held council.

Treaty 1 key players

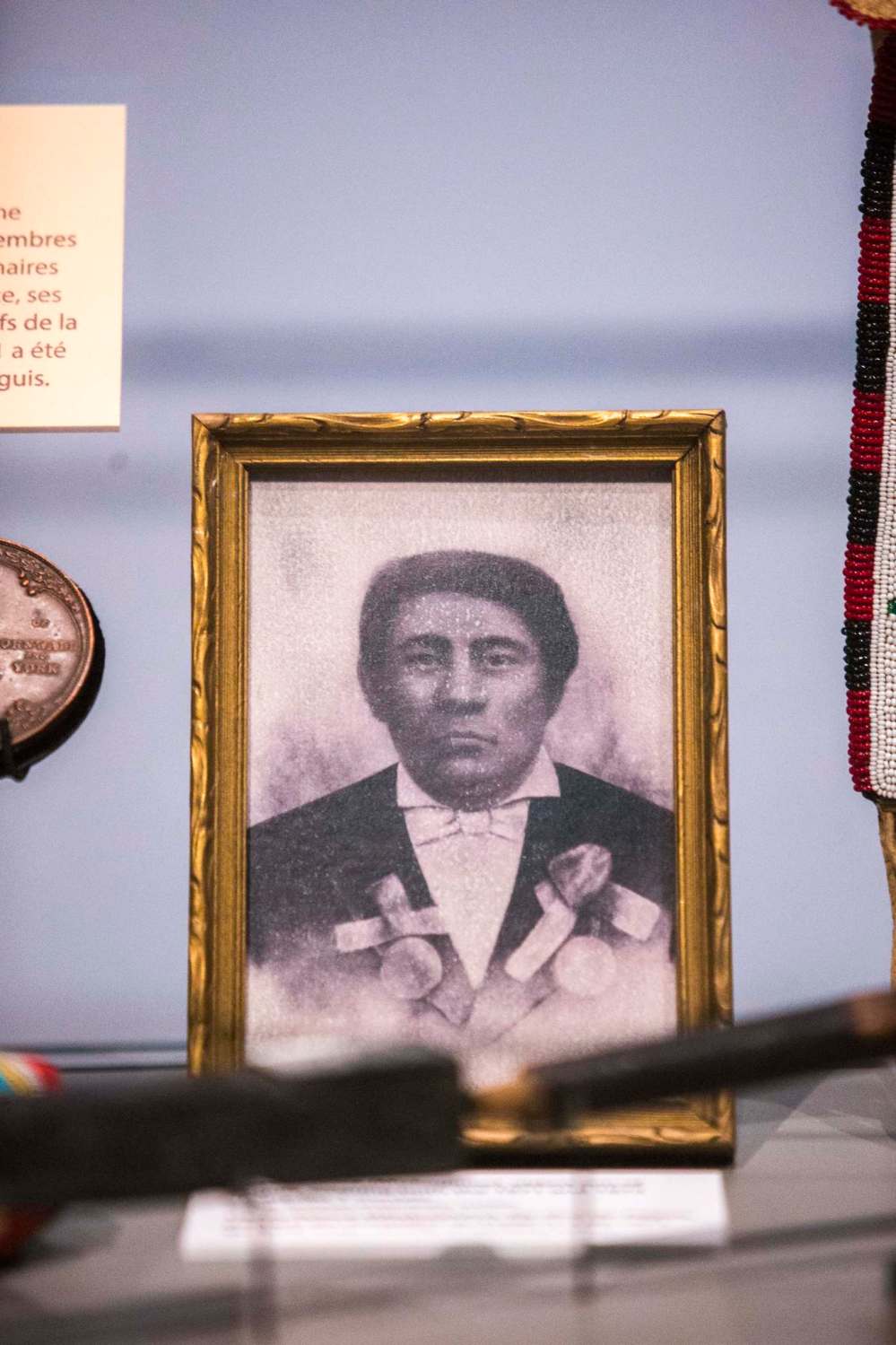

Chief Henry Prince: Chief of the Peter’s band, one of the leading negotiators during Treaty 1. Prince was the son of Chief Peguis who negotiated the Selkirk Treaty in 1817. Prince pushed early for treaty talks and was largely responsible for convincing Indian Commissioner Wemyss Simpson to provide First Nations with farm implements.

Chief Yellow Quill: Chief of the Portage band. Yellow Quill was one of several chiefs who negotiated Treaty 1. He later refused in 1875 to sign the so-called “outside promises” addendum to Treaty 1 over a dispute with Ottawa over size and location of his band’s reserve.

Chief Ayee-ta-pe-pe-tung: Also from the Portage band, Ayee-ta-pe-pe-tung was one of the most vocal chiefs during Treaty 1 negotiations and often protested federal negotiators’ tactics during talks. He and the Portage band walked out of negotiations the day before the treaty was signed Aug. 3.

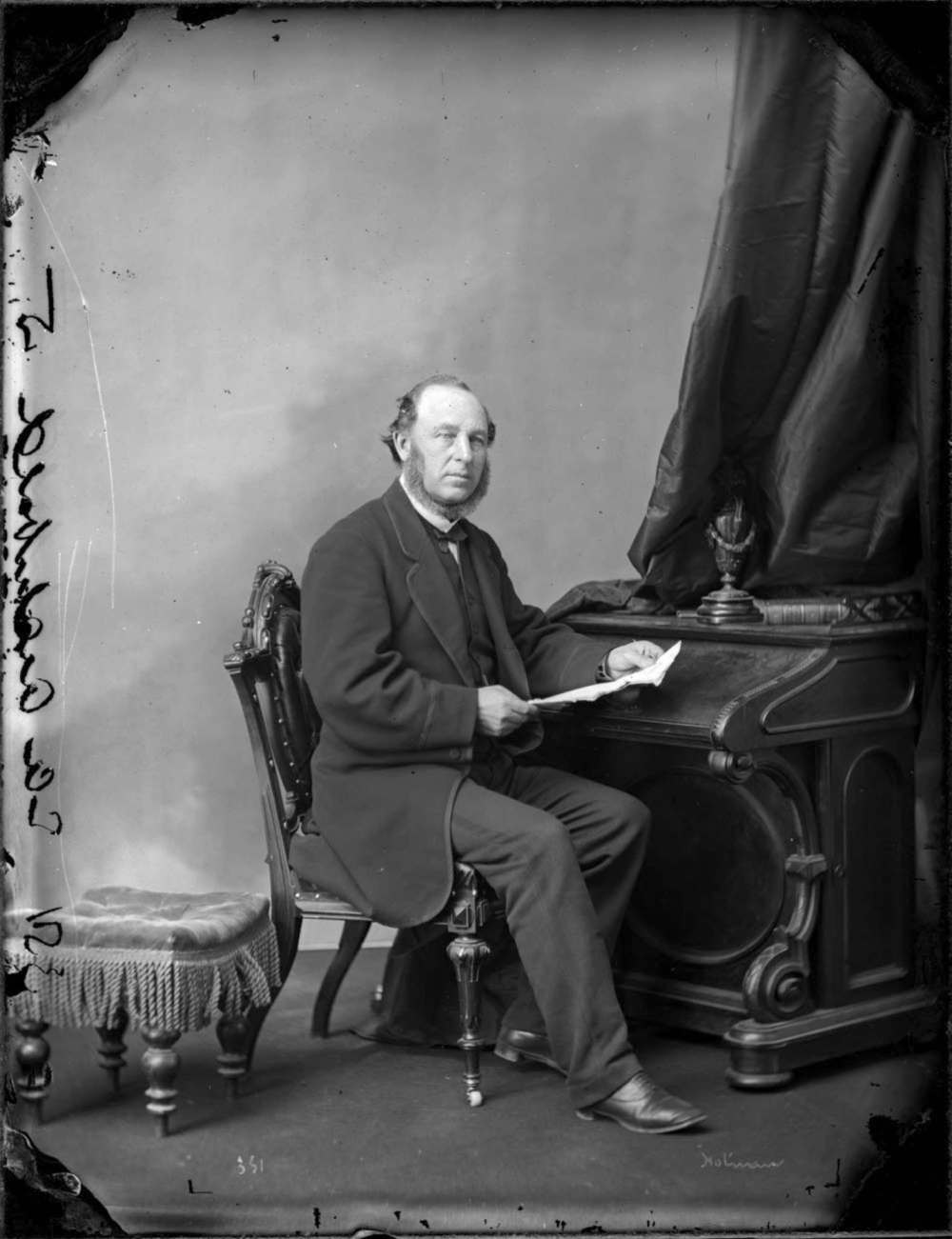

Wemyss Simpson: Indian commissioner appointed by the federal government to negotiate Treaty 1 on behalf of Canada. Simpson was a former Conservative MP from Ontario and served as a guide for Canada during the Red River Expeditionary Force in 1870.

Adams Archibald: Manitoba’s first lieutenant-governor who assisted Simpson in negotiating Treaty 1. Archibald made many promises to First Nations chiefs during negotiations that were excluded from the written text of the treaty. A Father of Confederation from Nova Scotia, Archibald would later clash with Simpson on how Treaty 1 was implemented.

James McKay: An Anglophone Métis who was an influential political figure in Red River and fluent in several Indigenous languages. McKay served as an interpreter and mediator during Treaty 1 talks. He was appointed by Archibald to Manitoba’s legislative council (the upper chamber, dissolved in 1876) and became its speaker.

These were the ancestors of First Nations from Brokenhead Ojibway, Long Plain, Peguis, Roseau River, Sagkeeng, Sandy Bay and Swan Lake. They came to negotiate a treaty with representatives of the new Dominion of Canada.

First Nations were accustomed to treaty making among tribes prior to the arrival of European settlers. Many had negotiated pacts with the Hudson Bay Company to secure trade relations and to grant the company access to Indigenous territory. While British colonies had negotiated treaties with First Nations in the east prior to Confederation in 1867, this would be the first formal alliance under the new country of Canada.

Negotiations were scheduled to begin July 25, 1871 outside the fort. Indian commissioner Wemyss Simpson, chosen by Ottawa to negotiate on behalf of Canada, arrived July 24. Archibald was there to represent the Crown.

Both sides were eager to negotiate a deal. Simpson came with marching orders from Ottawa to “extinguish Indian title” to lands required for settlement in the North-West, at the lowest cost possible to government. First Nations sought to retain as much of their territory and way of life as they could, while demanding compensation for land shared with newcomers.

First Nations were aware of Ottawa’s desire to settle the West peacefully and avoid violent conflict. Many bands had already resisted the encroachment of white settlers, who were occupying land and cutting wood without consent.

There’s little doubt the federal government viewed Indigenous people in the West as a threat. It’s one of the main reasons Ottawa deployed troops to the area less than a year earlier, following the Red River Resistance.

Written instructions to Archibald at the time from Howe confirmed that: “You are aware that the unsettled state of things in the North-West has compelled the Queen’s Government to despatch a military force into that country with a view to protect Her Majesty’s subjects from the possible intrusion of roving bands of Indians by whom they are surrounded, and to give stability to the civil government which it will be your duty to organize.”

Canada was compelled by the British government, under the terms of acquiring Rupert’s Land from HBC, to negotiate treaties with First Nations prior to settlement. The federal government was also obligated under the Royal Proclamation of 1763 to do so, which stipulated treaty talks had to occur at a “public meeting.”

First Nations had some leverage at the negotiating table, but it was limited. While Ottawa had a duty to negotiate in good faith, their commitment to it was dubious.

Archibald and Simpson repeatedly threatened chiefs during the talks with the ultimatum that if they didn’t accept what Ottawa was offering, settlers would occupy their lands anyway and Indigenous people would be left with nothing. Archibald told the chiefs it was God’s will that the North-West should be settled and used for farming “to raise great crops for all his children.” Ottawa’s offer may not have been a take-it-or-leave it proposition, but it wasn’t far off. There’s little doubt federal negotiators had the upper hand.

“White people will come here and cultivate it (the land) under any circumstances,” Archibald told the chiefs. “No power on earth can prevent it.”

That power imbalance was not lost on First Nations chiefs.

“I know our great mother the Queen is strong, and that we cannot keep back her power no more than we can keep back the sun,” Chief Ayee-ta-pe-pe-tung, representing the Portage band, told Simpson during the fourth day of talks. “If therefore the commissioner wants the land, let him take it.”

The government’s ultimatum wasn’t the only tactic used to try to dominate talks. Archibald brought troops with him to showcase government’s colonial authority.

“Military display has always a great effect on savages, and the presence, even of a few troops, will have a good tendency,” he wrote several days before talks began.

Even the physical positioning of the two sides — federal officials under an awning shielded from the elements and First Nations leaders in the open air, rained on at one point during discussions — was symbolic of the lopsided talks.

Still, Indigenous leaders had some bargaining power, which they exploited as far as they they could, making what Simpson and Archibald claimed at one point to be “outrageous” demands.

Government officials knew Treaty 1 would serve as a template for subsequent treaty negotiations and sought to limit concessions as much as possible.

“The terms we now agree upon will probably shape the arrangements we shall have to make with all the Indians between the Red River and the Rocky Mountains,” Archibald wrote.

Two days after negotiations were scheduled to start, all representatives had arrived. The stage was set. History was about the begin.

● ● ●

July 27, 1871

Negotiations began with a spectacular opening ceremony by the Anishinaabe inside Lower Fort Garry. Simpson, Archibald and a large gathering of local residents and government officials were among the spectators.

“The performances, between ribbons, feathers, paint and clothing, exhibited all the colors of the rainbow,” The Manitoban newspaper reported. “There were two orchestras, half women and half men, one set playing for one style of dancing, and the other for another and very different one. The band and performers were all seated on the grass, and the commissioner, lieutenant-governor and party, and a great crowd formed the spectators. Some of the chiefs and braves were in the most fashionable style of dress — that is, dressed as little as possible; having merely breechcloths on; others had buffalo horns, &c., on their heads, while bears’ claws, and similar remembrancers were plentifully scattered through the group.”

Talks got under way at 4 p.m., following the opening ceremony. Simpson, who stepped down earlier that year as a Conservative Member of Parliament to accept the position of Indian Commissioner, was dressed in military garb (he was appointed an officer in the militia for treaty talks). Archibald, in his Windsor suit, was accompanied by his aide-de-camp. The two government officials “were screened from the sun by an awning, under which several ladies and officers also found seats,” The Manitoban reported. “From the far end of the camp, the Indians moved to meet the commissioner en masse, the chiefs occupying the foremost rank.”

The chiefs sat in the front row. Among them were Henry Prince from the St. Peter’s band (Peguis), Tachou-chous from Fort Alexander, Red Deer from Brokenhead and Chief Yellow Quill from the Portage band. Interpreters were present for both sides. Archibald and Simpson did most of the talking on the first day.

“Your Great Mother wishes the good of all races under her sway,” Archibald said during his opening address, invoking the authority of Queen Victoria, the reigning British monarch at the time, while appealing to the cultural importance of kinship among his Indigenous audience. “She wishes her red children, as well as her white people, to be happy and contented. She wished them to live in comfort.”

Archibald laid out in broad strokes what government was offering: Newcomers would arrive in the North-West to farm and occupy unspecified amounts of territory, while the federal government would set aside land, called reserves, for the exclusive use of Indigenous communities. Those reserves could be used for farming, or any other purpose, “by you and your children forever,” he said.

“She will not allow the white man to intrude upon these lots.”

What the approximately 1,000 Indigenous people present during Treaty 1 negotiations didn’t know was, five years later, the federal government would pass the Indian Act.

As long as the sun shall shine “there shall be no Indian who has not a place that he can call his home, where he can go and pitch his camp, or, if he chooses, build his house and till his land,” the lieutenant-governor said.

Prince, Yellow Quill and the other chiefs couldn’t have known it at the time, but what Archibald said next was a foreshadow of the colonial relationship that would develop between Canada and First Nations for the next 150 years: The Queen would like “her red children” to live more like white people.

“She would like them to adopt the habits of the whites, to till land and raise food, and store it up against a time of want,” Archibald said. “She thinks this would be the best thing for her red children to do; that it would make them safer from famine and sickness, and make their homes more comfortable.”

Adopting “civilized habits” would not be forced on First Nations, Archibald insisted. The Queen was simply urging them to do so.

“This she leaves to your choice, and you need not live like the white man unless you can be persuaded to do so with your own free will,” he said. “When you have made your treaty, you will still be free to hunt over much of the land included in the treaty. Much of it is rocky, and unfit for cultivation; much of it that is wooded, is beyond the places where the white man will require to go, at all events, for some time to come.”

What the approximately 1,000 Indigenous people present during Treaty 1 negotiations didn’t know was, five years later, the federal government would pass the Indian Act. The legislation, at first a culmination of existing “Indian policies” already in place, would become the main instrument used by Ottawa to dominate every aspect of First Nations’ lives, with the express intent of extinguishing their language, culture and way of life, including the use of residential schools. The statute and its subsequent amendments, which made First Nations wards of the state, would be in direct contravention of what Anishinaabe chiefs were promised during the summer of 1871 at the Stone Fort.

Simpson followed Archibald with his opening remarks. He reaffirmed most of what the lieutenant-governor said, but also sought to lower their expectations: the government is offering First Nations land for farming, but they should not expect “immense reserves” beyond what is needed for agricultural purposes. Reserve sizes would be one of the main sticking points during negotiations.

“The government will give to the Indians reserves amply sufficient,” said Simpson. “The different bands will get such quantities of land as will be sufficient for their use in adopting the habits of the white, should they choose to do so.”

Until then, the chiefs sat and listened. Chief Henry Prince, the son of the late Chief Peguis, who negotiated the Selkirk Treaty in 1817, was the first to come forward. He shook hands with the commissioner and the lieutenant-governor and said in his language: “It is many years ago since I first heard such gentlemen would come among us; but this is the first time I have heard the Queen’s representative. I am very much obliged to His Excellency for the kind advice he has given us, and in hearing the commissioner this evening. I feel that we heard the Queen’s voice. That is all I have got to say at present. I will go back to the camp and select a spokesman.”

Chief Ayee-ta-pe-pe-tung was less optimistic.

“This day is like a darkness to me and I am not prepared to answer,” he said, after shaking hands with the commissioner. “All is darkness to me how to plan for the future welfare of my grandchildren.”

Simpson promised to send tobacco to the camp. The meeting was adjourned to 10 a.m the next morning.

July 28, 1871

Lower Fort Garry was not just a Hudson’s Bay Company trading post in 1871. It also served as a jail. Among those in custody during treaty talks were four Indigenous men from the Portage band who were found guilty, under a recently passed provincial law, of deserting their posts as boatmen with the HBC. They couldn’t pay their fines so were jailed for 40 days.

Ayee-ta-pe-pe-tung said he couldn’t negotiate while his men were jailed and requested they be released. Archibald agreed “as a matter of favour, not as a matter of right,” and only after a lecture about how people of all races were equal under the law, and that Indigenous people would have to obey the laws of the land.

“The discharge of the prisoners had an excellent effect,” Archibald wrote to Ottawa the next day.

With that out of the way, Simpson provided further details of what the federal government was offering. In addition to reserves set aside for farming, Ottawa would provide each Indigenous person with an annuity, in cash or goods, in perpetuity. The opening offer was $12 per family of five.

Reserves would be determined in consultation with Indigenous leaders, Simpson explained. They would be separate from unoccupied land, which could still be used as hunting grounds, he said.

The chiefs said they needed to consult further. Talks resumed the next day.

July 29, 1871

Several chiefs, including Ka-ma-twa-kan-nas-nin, representing Fort Alexander and Oak Point, and Wa-sus-koo-koon speaking for First Nations between Pembina and Fort Garry, made their first counteroffer. They proposed specific reserve sizes, some of which were close to 200 square-miles.

Simpson was taken aback. While government was willing to set aside modest areas of land, what the chiefs were proposing was out of the question, he said.

“If all these lands are to be reserved, I would like to know what you have to sell,” Simpson told the chiefs. He said the demands were “so preposterous” that if granted, there would be virtually no land left to cede for settlers. He urged the chiefs to reconsider.

Archibald reported to Ottawa later that day that it appeared the chiefs “misunderstood” the government’s intentions.

“When we met this morning, the Indians were invited to state their wishes as to the reserves, they were to say how much they thought would be sufficient, and whether they wished them all in one or in several places,” Archibald wrote. “In defining the limits of their reserves, so far as we could see, they wished to have about two-thirds of the province.”

What government had in mind was 160 acres per family– a “generous” offer that would give First Nations a head start over white settlers, Archibald said. Indigenous people in the east signed similar treaties and were “enjoying all the rights and privileges of white men,” he told the leaders.

The amount of land chiefs initially requested “amounted to about three townships per Indian, and included the greater part of the settled portions of the province,” Simpson wrote several days later, in correspondence to Ottawa. “When their answer came it proved to contain demands of such an exorbitant nature, that much time was spent in reducing their terms to a basis upon which an arrangement could be made.”

What government had in mind was 160 acres per family — a “generous” offer that would give First Nations a head start over white settlers, Archibald said. Indigenous people in the east signed similar treaties and were “enjoying all the rights and privileges of white men,” he told the leaders.

The chiefs were urged to “dismiss all nonsense” about wanting large reserves. For the first time during talks, the threat was raised that if First Nations didn’t take what was on the table, they would get nothing in the future.

“We told them that whether they wished it or not, immigrants would come in and fill up the country,” Archibald wrote later that day. “That every year from this one twice as many in number as their whole people there assembled would pour into the province and in a little while would spread all over it, and that now was the time for them to come to an arrangement that would secure homes and annuities for themselves and their children.”

The chiefs were told to take the rest of the weekend to consider government’s offer and return Monday with an answer. There were no talks Sunday.

July 31, 1871

There was little consensus between the chiefs and government officials after three days of talks. Simpson believed he was close to a deal, but had obviously misread the chiefs. “As far as I can judge, I am inclined to think that the Indians will accept these terms,” he wrote on July 30.

However, Simpson was met mostly with opposition on the fourth day of talks. Ayee-ta-pe-pe-tung told Simpson he saw little in what government was offering that would benefit his children. He said he was prepared to walk away from the table.

Timeline

1869-70 – The Red River Resistance. Red River settlers, led by the Métis, oppose Canada’s attempt to unilaterally annex the Red River Settlement and the Northwest; force Ottawa to negotiate Manitoba’s entry into Confederation. First Nations are left out of negotiations.

July 15, 1870 – Manitoba officially joins Canada, becomes its fifth province.

1869-70 – The Red River Resistance. Red River settlers, led by the Métis, oppose Canada’s attempt to unilaterally annex the Red River Settlement and the Northwest; force Ottawa to negotiate Manitoba’s entry into Confederation. First Nations are left out of negotiations.

July 15, 1870 – Manitoba officially joins Canada, becomes its fifth province.

August 1870 – Red River Expeditionary Force, led by Col. Garnet Wolseley, arrives in Red River. Some members of Canada’s volunteer militia and other Canadian settlers attack and intimidate local Indigenous people, driving some – including leader Louis Riel – out of the Red River Settlement.

September 1870 – Manitoba’s first lieutenant-governor Adams Archibald arrives in Manitoba, meets with several First Nations chiefs who demand treaties with Canada.

July 1871 – About 1,000 First Nations people gather at Lower Fort Garry to negotiate Treaty 1 from July 27 to Aug. 3.

Aug. 3, 1871 – First Nations and Canada sign Treaty 1. Many promises made during negotiations are omitted from the written text of the treaty.

1875 – After years of lobbying the federal government, First Nations signatories to Treaty 1 convince federal government to add some of the oral promises made during negotiations to the written text of the treaty, known as the “outside promises.”

Boundaries as set out in Treaty 1:

The Chippewa and Swampy Cree Tribes of Indians and all other the Indians inhabiting the district hereinafter described and defined do herby cede, release, surrender and yield up to Her Majesty the Queen and successors forever all the lands included within the following limits, that is to say:

Beginning at the international boundary line near its junction with the Lake of the Woods, at the point due north from the centre of Roseau Lake; thence to run due north to the centre of Roseau Lake; thence northward to the centre of White Mouth Lake, otherwise called White Mud Lake; thence by the middle of the lake and the middle of the river issuing therefrom to the mouth thereof in Winnipeg River; thence by the Winnipeg River to its mouth; thence westwardly, including all the islands near the south end of the lake, across the lake to the mouth of Drunken River; thence westwardly to a point on Lake Manitoba half way between Oak Point and the mouth of Swan Creek; thence across Lake Manitoba in a line due west to its western shore; thence in a straight line to the crossing of the rapids on the Assiniboine; then due south to the international boundary line; and thence eastwardly by the said line to the place of beginning.

“After I showed you what I meant to keep for a reserve, you continued to make it smaller and smaller,” he said. “Now, I will go home today, to my own property, without being treated with. You (the commissioner) can please yourself.”

Archibald tried a new tact, suggesting First Nations in Manitoba didn’t have a legitimate claim to the land in question because their tribes, the Chippewas (another name for the Saulteaux, who are Anishinaabe) were originally from the east. They didn’t occupy the territory 100 years earlier, he said.

“When the buffalo went westward, the Crees went with them; and the Chippewas, finding the land unoccupied, came in and stopped here,” Archibald said. “But they have no right to the land beyond that.”

Besides, what Ottawa is offering First Nations in Manitoba is similar, or even more generous, to what Indigenous people received through treaties in the east, Archibald said.

“Is the Indian in this country so much better than the Indian of the Lake of the Woods, or Lake Superior, that he must receive better terms?”

Ayee-ta-pe-pe-tung challenged Archibald on his assertion First Nations in Manitoba didn’t have a true claim to the territory, prompting Simpson to intervene. The commissioner suggested some “evil bird was whispering in council.” Negotiations grew tense.

Both Simpson and Archibald continued to threaten that it would be “unwise” and “foolish” for the chiefs to turn down their offer, repeating that “white people” would be coming into the province no matter what. Without a treaty, First Nations would be left with no land to cultivate.

Wa-sus-koo-koon raised an important point: What happens when First Nations families have more children and their communities grow? Where will their land be?

Archibald said government would accommodate that growth by giving First Nations more land as required.

“Whenever his children get more numerous than they are now, they will be provided for further west,” said Archibald. “Whenever the reserves are found too small, the government will sell the land and give the Indians land elsewhere.”

It was an unusual offer, considering Archibald had no authority to promise more land than what Simpson had offered. It was one of many oral promises made during the talks that were not included in the written text of the treaty (some of which were added in 1875 in what became known as the “outside promises”). The commitment to provide additional land to accommodate growing Indigenous communities was never fulfilled by the federal government.

Negotiations continued throughout the day. Finally, a small breakthrough: Ayee-ta-pe-pe-tung said he would agree to a treaty if the annuity was increased from $12 per family of five to $3 person.

Simpson seized on it immediately.

“I take you at your word at once,” said the commissioner. “The additional sum is not large, and I will take it on myself to make the amount up to $3 a head. You will get the amount of reserves we offer, and the annuity you have asked, and we will finish the matter at once.”

But not everyone was satisfied. Ayee-ta-pe-pe-tung said he only spoke for his own band. Simpson, growing impatient, threatened to end negotiations unless the chiefs came to an agreement the next day.

Aug. 2, 1871

There were no talks Aug.1, owing to bad weather. Archibald also had business to attend to in Winnipeg. Both sides had additional time to consider each other’s position.

Simpson demanded a final answer. This would be the last day of sitting, he said.

However, the chiefs still had questions. Chief Henry Prince said he wanted to know how government would treat Indigenous people under the treaty.

“The land cannot speak for itself,” he said. “We have to speak for it and want to know fully how you are going to treat our children.”

He also wanted to know how First Nations were supposed to take up farming if they had no equipment and livestock.

“The Queen wishes the Indians to cultivate the ground,” said Prince. “They cannot scratch it — work it with their fingers. What assistance will they get if they settle down?”

Archibald said the Queen was willing to help First Nations any way she could, including providing a school and a schoolmaster for each reserve and plows and harrows for those willing to farm.

The chiefs made another counteroffer: They wanted clothes for their children every spring and fall, fully furnished homes when requested, plows and cattle, buggies for the chiefs, councillors and braves, hunting supplies, and tax-free status on reserves.

“If you grant this request,” Wa-sus-koo-koon said, “I will say you have shown kindness to me and to the Indians.”

Simpson’s reply drew laughter from both sides, including from Wa-sus-koo-koon.

“I am proud of being an Englishman,” Simpson said. “But if Indians are going to be dealt with in this way, I will take my coat off and change places with the speaker, for it would by far better to be an Indian.”

Aug. 3, 1871

Whatever was agreed to during the final day of talks to reach an agreement is missing from the historical record. The Portage band and its chief abandoned the negotiations before the end of the previous day. Other chiefs were reportedly considering doing the same. However, one of the interpreters and a key political figure in Red River, James McKay — an Anglophone Métis — helped bring the two sides together the next day.

“All the Indians met His Excellency and the Commissioner today in better humour,” The Manitoban reported. “The Commissioner said he understood they were disposed to sign the treaty…”

In addition to what was agreed to thus far, including 160 acres of reserve land per family, a $3 per person annuity, farm implements, and a school on each reserve, each person would receive a one-time $3 “present,” each reserve would get a pair of oxen and buggies would be supplied to each chief.

“This gave general satisfaction, and the treaty was soon signed, sealed and delivered, with all due formality,” The Manitoban reported. “The ceremony was witnessed by a large crowd of spectators.”

It’s unclear the full extent of what was agreed to. Given the language barriers, it’s also unknown whether the chiefs understood everything that ended up in the written text of the treaty. Nevertheless, it appears common ground was found on how to share the land Canadian settlers would soon occupy. The specifics of that remain the subject of debate to this day.

Treaty 1 remains an important legal document and is the basis upon which land continues to be transferred through Manitoba’s Treaty Land Entitlement process. Much of the former Kapyong Barracks military site on Kenaston Boulevard — now named Naawi-Oodena — was obtained by the Treaty One Nation as a treaty obligation, following a lengthy court battle with the federal government.

Treaty 1 land acknowledgements are now regularly made at the beginning of meetings, news conferences, council meetings, school days and sporting events, including Winnipeg Jets and Winnipeg Blue Bombers home games. They acknowledge that Winnipeg and much of southern Manitoba are on the traditional gathering places of the Anishinaabe, Cree, Oji-Cree, Dakota and Dene people, and the traditional homeland of the Métis people.

tom.brodbeck@freepress.mb.ca

Tom Brodbeck is an award-winning author and columnist with over 30 years experience in print media. He joined the Free Press in 2019. Born and raised in Montreal, Tom graduated from the University of Manitoba in 1993 with a Bachelor of Arts degree in economics and commerce. Read more about Tom.

Tom provides commentary and analysis on political and related issues at the municipal, provincial and federal level. His columns are built on research and coverage of local events. The Free Press’s editing team reviews Tom’s columns before they are posted online or published in print – part of the Free Press’s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Friday, July 30, 2021 8:41 PM CDT: Fixes typo in "unusual offer" sentence