‘I had no idea that I built a bad guy’ Three artists talk about the John A Macdonald statues they made — and what’s happening to them

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 13/06/2021 (1644 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Mike Halterman’s bronze sculpting studio sits smack in the middle of rural Colorado, outside the town of Cripple Creek — “nine miles of bad road, and a few on the pavement,” he says.

It’s 32 kilometres northeast — as the crow flies — from Cripple Creek to Colorado Springs, the nearest city, but you have to travel a 72-kilometre loop around Pikes Peak to get there by road. Cripple Creek itself is a former ghost town, brought back to life in the ’90s by casinos and mining. Its population is slightly more than 1,000 and it has no stoplights.

Halterman himself doesn’t follow much Canadian news — just what people forward him — though he comes to Canada from time to time with his wife, visiting her relatives. This year will mark his 40th year making bronze sculptures in that remote studio.

Small wonder, then, that he’s puzzled to find himself in the swirl of a Canadian controversy — the reverberations of which have managed to travel cross-country to his studio — over something he did in Charlottetown 13 years ago.

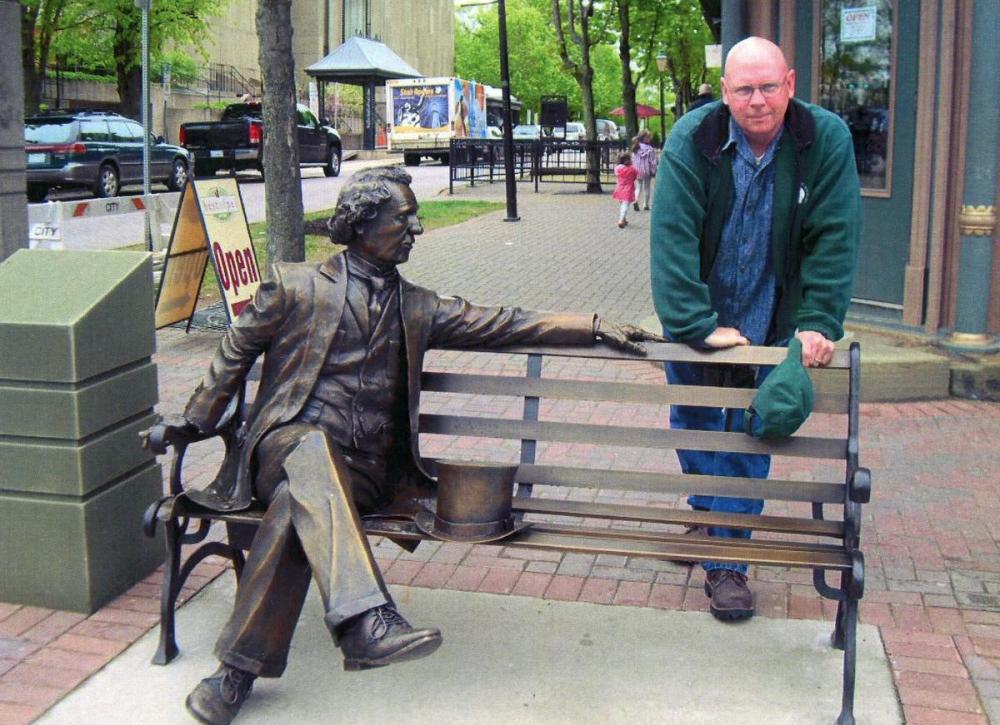

That something was a sculpture of Canada’s first prime minister, John A. Macdonald, sitting on a park bench, the seat to his left vacant. It sat in Victoria Row in Charlottetown, the birthplace of Confederation.

Or rather, that’s where it used to sit.

But public sentiment about Macdonald has changed since that statue was installed in 2008, and more people in this country are taking a hard look at his racist attitudes and role in creating Canada’s residential schools for Indigenous children.

That scrutiny was intensified with the late May discovery of the bodies of 215 Indigenous children on the former grounds of the Kamloops Indian Residential School.

Statues of Macdonald have become lightning rod of sorts for the resulting anger.

The Star talked to three artists who created some of those statues for their perspectives on work that has recently been scrutinized, criticized and vandalized.

Mike Halterman, Macdonald statue in Charlottetown

Last summer, the Halterman’s statue in Charlottetown was repeatedly defaced with red paint, mirroring similar protests at statues across the country, including the toppling of a Macdonald statue in Montreal.

That was the summer Halterman, in remote, rural Colorado began to get emails from Charlottetown.

Not hate mails, he is quick to say, but people voicing their opinion — though one writer did call him a hater. They asked him not to come to Charlottetown, not to work on modifying his Macdonald statue, a project he had been discussing with the city.

Charlottetown council had, after much debate, settled on a plan earlier this year to leave its Macdonald statue in place, but to modify it to reflect a fuller perspective on the man. An Indigenous elder was to be added to the empty space on the bench, in effect conversing with the first prime minister. Halterman, contacted by the city, said he was happy to do the work, even thought it would balance the piece out, he said — sociopolitically as well as compositionally.

But that changed in the wake of the Kamloops discovery; within days, the city council had removed the statue to storage, leaving the artist — who grew attached to the statue during the hectic eight-month marathon build — quite disappointed.

“I had no idea that I built a bad guy,” says Halterman, who took the commission from the city of Charlottetown after returning a public request for proposals. “I thought I was doing something cool — the first prime minister of Canada. And I did some homework on him, and I heard he was a bit of a drunkard and pretty colourful like that, and that’s fine with me. And I just thought, ‘This is a nice project. It’d be fun to do.’”

Perhaps tellingly, he says that in all the reading he did on Sir John A. before starting work, back in 2008, he didn’t come across Macdonald’s history of racism, nor his involvement in starting the residential schools. Nor did the people he was working with in Charlottetown tell him any such thing.

“I heard he was a bit of a drunkard and pretty colourful like that, and that’s fine with me. And I just thought, ‘This is a nice project. It’d be fun to do.’”–Mike Halterman

Art is supposed to elicit emotion, says Halterman. Some people will love your work; others will hate it. In the case of his Macdonald statue, the hate is all about the subject matter. And when you take a commission, he says, you don’t get to choose the subject.

Now, seeing the backlash and taking the political temperature of the day — both here and in the U.S. — he says he might think twice about taking that commission again.

“I’ve never had this happen. This is all new to me,” he says. “In what? Thirteen years? That public sentiment can change that quickly? Everybody was really happy when I was up there and put it in for them. All ‘thank yous’ and all that good stuff.

“I didn’t think anything like this would ever happen.”

John Dann, Macdonald statue in Victoria, B.C.

“Public sculptures are not about art; they haven’t been for a hundred years,” says John Dann.

Dann’s statue of Macdonald — installed in 1981, on a commission from the John A. Macdonald Society of Vancouver — was removed from the front steps of Victoria’s City Hall in August of 2018, an act of reconciliation with the city’s Indigenous communities.

Public sculptures used to be about art, he says.

Rodin studied the writer Honoré de Balzac for seven years before creating his Monument to Balzac, striving not so much for his physical likeness, but seeking to capture the spirit of the writer instead.

Yet when the sculpture was finished, critics hated it. Rodin took it home with him, and it was not until two decades after his death that it was cast in bronze and installed on the Boulevard du Montparnasse in Paris, where it stands today.

Today, the Museum of Modern Art calls it, “a visual metaphor for the author’s energy and genius.”

Now, says Dann, it seems public sculptures are more about advertisement.

“If somebody calls you up and says, ‘I understand you’re a sculptor. We’d like you to do a sculpture of Oprah,’ … what they want is a blob of bronze on which they can put the words ‘Oprah: donated to such and such by this committee. That’s what they want — a place on which they can put a plaque.”

That’s not how Dann would like to think of his work — including that Macdonald statue.

For him, he’d like people to think of his sculpture as a work of art first, a commemorative piece afterwards, the kind of thing where, if one didn’t know the identity of the subject, one might instead wonder about the figure’s body language, the curl of a lip, the cant of an eye, the drape of their clothing, the position of its hands.

The Macdonald sculpture was the last piece of portrait sculpture he did. Forty years ago, when that statue was installed, Dann was in his late 20s and admittedly naïve. He said he didn’t know about the residential schools. He doesn’t make excuses for that.

But now he’s in his late 60s, older and wiser. And he believes we shouldn’t be doing these public sculptures at all.

“Canada is not written,” he says. “Canada is that green earth, that blue sky, that rich dirt you can get between your toes. Canada is the ocean, the sea. We don’t have any respect for the sea. But the Indigenous People’s culture does. We need to learn that that’s what we need, rather than treating them as we do still, with disrespect.”

“Maybe we found a use for art after all. By tearing it down.”–John Dann

Dann believes we shouldn’t be complaining about Macdonald statues or tearing them down — though from an artistic point of view, he doesn’t object. Instead, he feels we should be embracing Indigenous culture as Canadian culture.

“If we can get to a point … that we’re looking with renewed respect at Indigenous culture and questioning the roots of our own British colonial past, then that’s progress,” he says.

“Maybe we found a use for art after all. By tearing it down.”

Ruth Abernethy, Macdonald statue in Baden and Picton, Ont.

Memorializing public figures is always going to be a moving target, says sculptor Ruth Abernethy, and as public sentiment changes, so too will perspectives on what should and shouldn’t be memorialized.

Abernethy’s Macdonald statues used to stand in Baden, Ont., and in Picton, Ont. The one in Baden — installed in June 2016 — was removed last summer, after having been doused with red paint.

The Picton statue, on the town’s Main Street, had also been the target of frequent vandalism and Abernethy had earlier been asked by the county to work with it on new, more appropriate accompanying signage.

But this past Monday, she received notice from Prince Edward County that the statue was being removed and going into storage.

That, for her, was disappointing, but also a sign that, for all its authors’ lofty proclamations, history is always in motion.

“I remember the (Berlin) Wall coming down,” she says. “We’ve seen these big symbolic figures come down in other places.”

“Did we ever think it wouldn’t happen here? Was that a thought?”

“But in scrutinizing this, my thought is that there will be no overarching policy that covers all figurative portraits, because they have to be taken case by case.”

That means that any time you think of removing a monument, she says, you should be examining, each time, in every situation, the reasons for doing so.

The three factors in that examination — what she calls “the three P’s” — are the person, the patron and the position.

First; the figure itself. The subject. What was that person like? What’s their legacy?

Over time, the way we perceive that person may change or perhaps merely the ability to shine light on ignored aspects of that person’s legacy may change.

“Complicated lives leave complicated legacies,” says Abernethy, and though she’s talking about Macdonald in this case, she could well be talking about any number of public figures enshrined in bronze or marble in any number of places.

In Macdonald’s case, the darkest parts of his legacy are now uppermost in the public consciousness. And that makes making the case for keeping those statues in place more difficult.

The second of Abernethy’s three P’s is the patron. Who arranged for that monument to be built? And what was their motivation?

In some cases, patrons build monuments to themselves or to curry favour with the subject. In others, it’s a projection of the patron’s world view or beliefs, in the expectation that those beliefs are shared by viewers.

In most cases, the patron wants the credit for their magnanimity. Abernethy recalls one proposal she dealt with where the plaque on the statue was to be a biography — not of the subject of the statue, but of the person who commissioned it. She rejected that commission.

The last of the Abernethy’s three P’s is the position of the monument, which refers to not only where, geographically the monument is located, but how it is situated and composed at that location — all of which makes a difference in the kind of impact it has on viewers.

She uses Nelson’s Common in London’s Trafalgar Square as an example. Smack in the middle of London, it is a towering 47-metre, granite Corinthian column commemorating Admiral Horatio Nelson, whose sandstone figure looks down on the square from atop.

“The whole idea (is) that you’ve conceived this individual, and you’ve elevated them to godlike status,” says Abernethy.

“I think anyone walking beneath has a certain element of being lesser-than, or that he is above the rest of us.”

Those three P’s, she says, are all very fundamental to how you present a memorialized character in its time, or after its time.

“Until you do the real due diligence on those three P’s, you cannot know even how you feel about them.”

The idea, perhaps, is that what we see as eternal monuments are really only as enduring as the shifting of perspectives — and of history — around them. And that is a concept the artist carries with her, even when it is her statues being removed.

“I don’t flinch,” says Abernethy. “What goes up can come down.”

“What I would hunger for in the dialogue is the more informed viewpoint, the really, truly factual (one). What staggers me is the decades of subsequent prime ministers and bureaucrats who can’t have not known that the system wasn’t serving Indigenous people and things weren’t changed.”

“I don’t let (John A.) off the hook. I don’t. But there is no reason that this individual should bear the brunt of the entire 19th century of bureaucrats and other elected leaders.”

Steve McKinley is a Halifax-based reporter for the Star. Follow him on Twitter: @smckinley1

.jpg?h=215)