Discord in fire-paramedic service burning out of control City's long-smouldering fire-paramedic services' marriage of convenience erupts in signs of irreconcilable differences

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$19 $0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for four weeks then billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Offer only available to new and qualified returning subscribers. Cancel any time.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 11/02/2021 (1414 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

There is a five-alarm fire raging in Winnipeg.

It’s coming from inside the fire halls.

While the latest controversy to roil the Winnipeg Fire Paramedic Service centres on the actions of a single medic and firefighting crew during a critical-care call in the North End last fall, the context in which it sits is a turbulent 24-year marriage between two departments that were forced to become one.

City misses deadline, taxpayers on the hook

The City of Winnipeg has missed a chance to put an end to a controversial arrangement that sees taxpayers on the hook for 60 per cent of the firefighter union president’s salary.

In 2018, news broke that due to an unusual agreement between the United Fire Fighters of Winnipeg and the city, taxpayers were paying most of Alex Forrest’s salary.

Forrest is a full-time union president. That year, his salary was $116,000.

As the controversy deepened, the city found itself unable to explain why it had entered into the arrangement with the union boss, precisely when it had gone into effect and the total amount of money taxpayers had sent Forrest’s way over the years.

Mayor Brian Bowman publicly expressed displeasure over the deal, which he made clear predated his time at city hall. He said the city would do what it could to put an end to the arrangement as soon as possible.

Forrest said the UFFW would be open to revisiting the matter at the next round of collective bargaining, scheduled to begin last fall.

But when the time came to submit proposals for collective bargaining last year, the city missed the deadline by two weeks. As a result, the UFFW has said it will not consider any of the city’s proposals.

The City of Winnipeg has missed a chance to put an end to a controversial arrangement that sees taxpayers on the hook for 60 per cent of the firefighter union president’s salary.

In 2018, news broke that due to an unusual agreement between the United Fire Fighters of Winnipeg and the city, taxpayers were paying most of Alex Forrest’s salary.

Forrest is a full-time union president. That year, his salary was $116,000.

As the controversy deepened, the city found itself unable to explain why it had entered into the arrangement with the union boss, precisely when it had gone into effect and the total amount of money taxpayers had sent Forrest’s way over the years.

Mayor Brian Bowman publicly expressed displeasure over the deal, which he made clear predated his time at city hall. He said the city would do what it could to put an end to the arrangement as soon as possible.

Forrest said the UFFW would be open to revisiting the matter at the next round of collective bargaining, scheduled to begin last fall.

But when the time came to submit proposals for collective bargaining last year, the city missed the deadline by two weeks. As a result, the UFFW has said it will not consider any of the city’s proposals.

“We will not discuss the proposals you sent… nor will we be providing you with any counterproposals to them,” Forrest wrote in a letter to the city that was leaked to media.

“There is simply a failure by the city to meet its deadlines, both pursuant to the collective agreement and pursuant to the act… There are consequences to that disaster of its own making.”

The current CBA expired on Dec. 26, and the UFFW has filed for binding arbitration. In the meantime, the two sides continue to try to negotiate a new deal.

The 2014 agreement that stipulated 60 per cent of Forrest’s salary be paid by taxpayers — which formalized a long-standing arrangement — also included a provision that allowed him to be promoted to captain while working for the union. That promotion resulted in a pay raise.

It is just one of many controversies that has marked the tenure of WFPS Chief John Lane.

Shortly after Forrest’s strange deal came to light, it was revealed that during the time taxpayers had been paying 60 per cent of his salary, the labour leader had taken at least 60 out-of-town trips for various union and firefighter-related events.

Meanwhile, Lane had also been racking up frequent-flyer miles, taking 34 out-of-town trips for city business between the time he was named chief in June 2015 and January 2018. And it was on one such trip in August 2015 that Lane breached respectful workplace policies against city paramedics.

Lane had presented, alongside Forrest, on Winnipeg’s integrated fire-paramedic model at a conference in Maryland. A summary of the presentation described the model as “continuously threatened by single-role EMS providers and misinformed leaders.”

Hundreds of Winnipeg paramedics took issue with that characterization and filed a respectful workplace grievance against their chief.

During the subsequent arbitration proceedings, text messages — sent as late as 1 a.m. — from Forrest to Lane were read aloud at the hearing. The messages from Lane to Forrest were not read aloud, as they had been deleted.

Multiple paramedics who spoke to the Free Press pointed to those texts as evidence for their contention that Lane and Forrest have an “inappropriate relationship” as chief and union boss. In March 2018, the arbitrator fined the city $100,000 for Lane’s actions.

Five months later, in August 2018, news broke that Winnipeg taxpayers were also paying for Lane to pursue a master’s degree. The city confirmed it had paid $19,800 of Lane’s post-secondary education costs up to that point, “in fulfilment of a mutual commitment.”

Between his salary, trips, education costs and the fine from the breach of respectful workplace policies, Lane cost Winnipeg taxpayers more than $300,000 in 2017.

In 2018, it was also revealed that when Prime Minister Justin Trudeau was in Winnipeg the previous year and visited one of the city’s busiest fire halls, he did so at the behest of Forrest, and both Lane and civic officials were unaware the event had occurred until after the fact.

— Ryan Thorpe

And since that fateful night last October, as accusations of racist conduct by WFPS members went from internal complaints to media reports to a third-party probe, deep tensions within the department have escalated from minor skirmishes and sneak attacks to open conflict and combat.

In order to better understand the history behind recent allegations of racism-fuelled patient neglect by first responders, the Free Press spoke to nine current and former WFPS employees — both paramedics and firefighters — to hear what they had to say about the state of the department.

Those sources — some of whom have spent decades of their lives in the trenches of emergency services in this city — paint a picture of a department in crisis, where animosity on both sides of a 1997 experiment in amalgamation has been allowed to fester.

The three firefighters who spoke to the Free Press pointed to concerns over disrespect and laziness from their paramedic colleagues, who they say do not pull their weight around fire halls and have engaged in a pattern of frivolous workplace complaints against them.

Meanwhile, six paramedics who agreed to be interviewed said they find themselves in a department where resources are not distributed equitably due to a perceived cosy relationship between WFPS Chief John Lane and United Fire Fighters of Winnipeg President Alex Forrest.

While some sources said firefighters and paramedics largely get along at “street level,” others complained of a “frat house” atmosphere in fire halls where racism and sexism — both implicit and explicit — has run rampant and toxic, macho behaviour has been allowed to go unchecked.

The nine firefighters and paramedics — seven of whom are currently employed within the WFPS in a variety of roles — spoke on the condition of anonymity. The Free Press has confirmed their employment in the department.

● ● ●

In September 1996, a 23-year veteran of what was then called the Winnipeg Fire Department submitted a master’s thesis in public administration at the University of Winnipeg.

His name was Gary Richardson and he would go on, indirectly, to change the face of emergency services in Manitoba’s capital for the next three decades.

While the thesis bore the clunky title of “An Analysis of Fire Department and Ambulance Integration from a Process Perspective: Utilizing Winnipeg, Manitoba as a Case Study,” the argument put forth in the document was clear.

The Winnipeg Fire Department, whose history in the city dates back to 1874 when property-owning citizens first put aside funding to fight fires, and the Winnipeg Ambulance Service, which was created in 1975 after being a private entity, could better provide emergency services under a single roof.

After more than two decades within the WFD, during which time he rose to the ranks of deputy chief, and more than “two years of study, interviews and research,” Richardson concluded that amalgamation was the clear path forward for Winnipeg.

He believed the amalgamated model, which had previously been considered and rejected in the city, would allow the municipal government to provide “more efficient and effective emergency services” to taxpayers.

Richardson recognized his proposal was not without pitfalls and that the devil, ultimately, would be in the details. Toward the end of his thesis, he quoted James Page, a 16-year firefighter/paramedic in Los Angeles, who had spoken out against such amalgamated models.

“In many areas of the U.S. the fire service is a house divided. The internal divisions of attitude and opinion have become a public spectacle. Despite the traditional resistance to outside interference with fire service affairs, the question of fire service/EMS will be decided by outsiders,” Page wrote in 1984.

“The ultimate product of EMS is patient care and few believe that quality patient care can be delivered by a house divided.”

“But very quicky it (amalgamation) became not so much of a good thing. What you had was a couple hundred paramedics thrust into a department with about a thousand firefighters. And that, right there, is where the problem begins.” – Retired paramedic

In that passage, Page was arguing against the integrated fire-paramedic model that Richardson was proposing. Nevertheless, Richardson said he believed Page had “inadvertently summed up the entire problem.”

“The ‘house divided’ can occur no matter what barriers exist between or among organizations. A single organization can be a house divided, but so too can two separate entities,” Richardson wrote.

By evoking the notion of a “house divided,” both Page and Richardson were riffing on an idea that has resurfaced throughout the ages, from the plays of William Shakespeare to the speeches of Abraham Lincoln, and which traces its roots to the Bible itself.

“Every Kingdom divided against itself is brought to desolation,” Jesus declared, “and every city or house divided against itself will not stand.”

In 1997, the year after Richardson submitted his thesis, the process of amalgamating the Winnipeg Fire Department and the Winnipeg Ambulance Service would begin under then-mayor Susan Thompson.

Soon after, Richardson accepted a job as fire chief in Ottawa, where he raised eyebrows with an off-the-wall proposal to turn the department into a money-making venture by leasing surplus equipment to the private sector.

Following the amalgamation of nine fire departments in Ottawa and the surrounding areas in 2001, Richardson left his job and moved back to Winnipeg. In 2005, he and his wife died in a motorcycle crash on the outskirts of the city.

The Free Press spoke to one paramedic (now retired) who worked for the city in the late-’90s as amalgamation was getting underway. By the time he retired in the mid-2000s, he had three decades of experience as a first responder.

“The ambulance department was quite mismanaged at the time, and so when we heard of a merger on the basis of a thesis this deputy fire chief wrote, a lot of paramedics were somewhat hopeful. Initially, it was seen as a good thing,” he said.

“But very quicky it became not so much of a good thing. What you had was a couple hundred paramedics thrust into a department with about a thousand firefighters. And that, right there, is where the problem begins.”

The paramedic said he and his ambulance colleagues soon felt like second-class citizens.

At the time, he said the paramedics union was “very weak,” and more of an association than a real union. Meanwhile, Alex Forrest was voted in as president of the United Fire Fighters of Winnipeg, a position he holds to this day.

“Forrest ran that department because of the power he held,” the paramedic said.

● ● ●

By the mid-2000s, the WFPS was already experiencing a lot of animosity between the fire and medic sides of the department.

Despite being hired as an ambulance-based paramedic at about that time, one source said his intention was always to transition into a firefighting role. After 18 months on the job, he became a firefighter-paramedic — a position relatively unique to Winnipeg among big cities because of its amalgamated model.

After years as a firefighter-paramedic, he eventually dropped his paramedic certification, and is now employed solely as a firefighter. Given the various roles he’s held, his perspective on the history and current state of the department is somewhat unique.

During his time as an ambulance paramedic, he said his partner — a seasoned veteran — took him under his wing, an experience that was “invaluable” in his development as a first responder. Nevertheless, it quickly became clear to him that his partner loathed firefighters.

“He hated firefighters. I mean, he hated them…. There was a lot of animosity. The ambulance paramedics were running all the time. A lot of them didn’t think the (firefighter-paramedics) were very good at their jobs,” the source said.

“But once I crossed over and became a (firefighter-paramedic), I saw a lot of the little things that paramedics do that grind the gears of the fire guys.”

The concerns raised by the three firefighters who spoke to the Free Press were similar. They contend paramedics are “lazy” when it comes to helping out with work at fire halls, such as mopping floors, cleaning the kitchen or doing yard work.

The firefighters also said paramedics often refuse to contribute to a communal “kitty” used to pay for groceries and various other things such as newspapers or additional TV channels for the entire staff.

“The oldest trick in the book by paramedics is when it’s right before (time to do fire hall chores) and they say, ‘Oh, we’ve got to go downtown for a meeting, or we’ve got to go get drugs or paperwork or whatever.’ They’ll disappear, and a lot of times just go to Tim Hortons to get a coffee,” he said.

“It may sound small and petty, but in the long run, these things are annoying. It’s a lack of respect. It’s like when your buddy comes over and drinks all your beer. It’s fine the first couple of times, but eventually you’re like, ‘Hey, bring over a six-pack or something.’”

But the major concern raised by firefighters interviewed by the Free Press was they feel their paramedic colleagues, as of late, have been engaged in a campaign to file frivolous complaints against them.

That concern came to a head on Oct. 7, when the WFPS dispatched a paramedic crew and a fire crew to a critical-care call in the North End after receiving reports that a 23-year-old Indigenous woman had stabbed herself in the throat.

“The headquarters, the chiefs, I just feel like they’re not stepping in and they’re letting things start at, ‘They don’t pay kitty. They don’t help out around the hall.’ And it’s spiralled out of control over the course of 30 years and it’s resulted in the bickering we have now.” – Firefighter

After an argument at the scene, a paramedic on the call — a person of colour — accused two of his firefighter colleagues of failing to provide medical care to the patient and delaying her transport to hospital.

Soon after, the paramedic took the allegation directly to Lane, and the city hired an independent consultant to probe the matter.

Last week, the Free Press reported the investigator concluded “implicit racial bias” against the patient and “racial animus” against the paramedic impacted the actions of the firefighter crew that night. Implicit bias describes the attitudes and stereotypes people have towards others without their conscious knowledge.

In his public comments on the situation, Lane emphasized the investigator did not find explicit anti-Indigenous racism on the call, but implicit — or unconscious — racial bias. Firefighters who spoke to the Free Press also repeatedly made that point.

But one paramedic said it seemed like an attempt to minimize what happened, and also shows an unwillingness to confront the reality that implicit racial bias in the context of health care can kill.

“Chief Lane likes to make a distinction between implicit and explicit bias. Well, explicit bias is rampant within the department. And you can’t just do this clean separation between the two and say, ‘implicit bias isn’t that bad,’ because it impacts patient care,” the paramedic said.

“Sexism is rampant in the department. Racism is rampant in the department… I would go to these stations and hear all these comments about ‘drunk Indians.’ It’s heartbreaking. It’s constant. It’s all of the time.”

On top of the findings of implicit racial bias and racial animus, the probe ruled the firefighters likely acted in retaliation against the paramedic, who was known to have filed complaints about allegedly racist conduct among WFPS members, particularly in social media posts.

The investigator ruled the firefighters failed to follow procedures, did not provide proper medical care, and delayed the patient’s transportation to hospital. The investigator also ruled the firefighter crew colluded to obstruct the probe.

One of the firefighters who spoke to the Free Press said he believes this incident — which has touched off a high-profile controversy and will be the subject of an upcoming disciplinary hearing — “had nothing to do with the patient’s ethnicity.”

While that firefighter was not at the scene, he has spoken to other members about the incident and has skimmed the investigator’s final report into the allegations.

“I think it has nothing to do with this patient’s race or degree of injury. I think it was a personality clash between the paramedic and the fire-paramedic. I think that’s what the main issue is. I don’t think it was racism at all. It’s the lack of respect and the fighting, and it’s just got to stop,” he said.

“The headquarters, the chiefs, I just feel like they’re not stepping in and they’re letting things start at, ‘They don’t pay kitty. They don’t help out around the hall.’ And it’s spiralled out of control over the course of 30 years and it’s resulted in the bickering we have now.”

● ● ●

Like their firefighter colleagues, the six paramedics who agreed to interviews largely spoke with a unified voice. The concerns they raised were consistent across the interviews.

The paramedics were also frustrated by expected contributions to the collective expense fund in fire halls. But according to the paramedics, the reason they resent contributing is because they often don’t share in the benefits.

“We’re overworked, we’re underfunded, and there are not enough ambulances. We’re getting run off our feet for 10, 11 hours every day, and then we come back to the station and we see them having their afternoon naps or sitting down and enjoying a nice big meal,” one said.

“Tell me another occupation where you eat and sleep together, you work out together, you plan meals together, you have a big family dinner together. There is no other job like that. That’s the crux of the problem. That’s why when we’re in the fire halls, we’re not one of the gang. We’re outsiders.”

But more important than concerns over upkeep in fire halls or contributions to communal meals — at least among paramedics — are concerns over the distribution of resources within the WFPS and the perceived outsized influence of Forrest, the firefighter union president.

Every paramedic the Free Press spoke to alleged Forrest, not Lane or anyone who has come before him, has been the true chief of the WFPS since the late-1990s. They also said the amalgamated model should be scrapped and the two services separated.

“I just really feel like firefighters shouldn’t be attending medical calls,” one paramedic said.

“It’s paramedic skills alongside expedient transport that makes the difference in whether someone passes away from their illness or injury, or if someone has a good patient outcome.”

The fact is no other large Canadian city operates its fire and paramedic services the way Winnipeg does. Only in Winnipeg — at least among big cities — do the number of paramedics working as firefighters exceed those working in ambulances.

Edmonton and Calgary both had amalgamated fire-paramedic services but chose to go back to separate departments. In his thesis on amalgamation, Richardson said the experience in Calgary should serve as a warning to Winnipeg.

“The lesson learned from Calgary is that no matter what model is chosen, if separate identities are maintained, problems will result. This is a basic human dynamic,” Richardson wrote.

The Winnipeg firefighters who are certified as primary-care paramedics are staffed on four-person fire trucks, which are often able to respond to medical calls before ambulances, due to the positioning of fire stations around the city.

And it is not as if this model doesn’t have benefits: the WFPS provides high-quality fire-suppression services with quick response times, and Winnipeg is one of the safest places in Canada to suffer a heart attack, as long as you call 911 and don’t arrange for private transportation to the hospital.

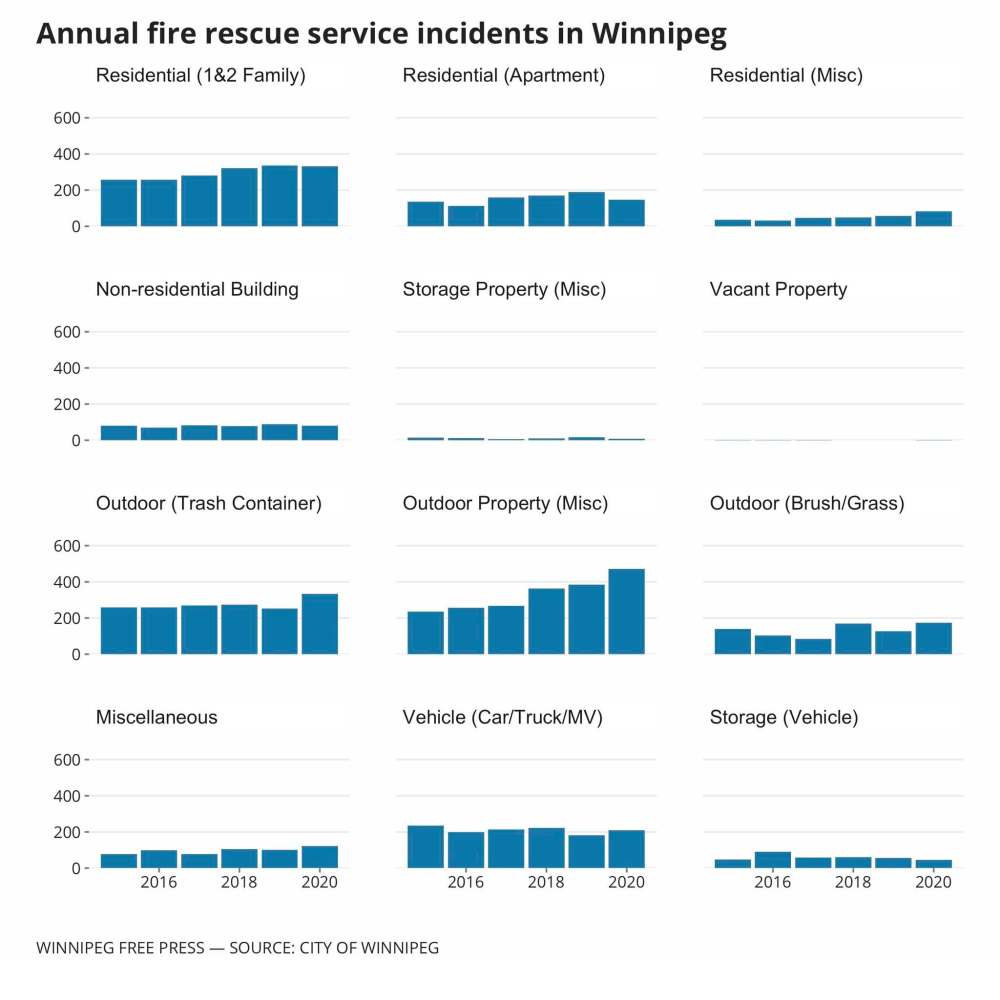

But from 2007 to 2017, the number of fires in Winnipeg fell — drastically. Fires were cut in half during that time, and in the years since, the numbers have continued to decline. In 2007, firefighters responded to 3,459 fires; by 2016, that number fell to 1,518.

A significant drop in fires came in 2013, when arsons fell by 41 per cent. That was the result of a city initiative to do away with thousands of garbage autobins and replace them with smaller carts for trash and recycling.

It is estimated that fires make up less than three per cent of all incidents that fire personnel respond to. The majority of calls — roughly 70 per cent — are medical in nature. The rest are miscellaneous, such as when an alarm goes off but there is no fire or when an unusual odour is reported.

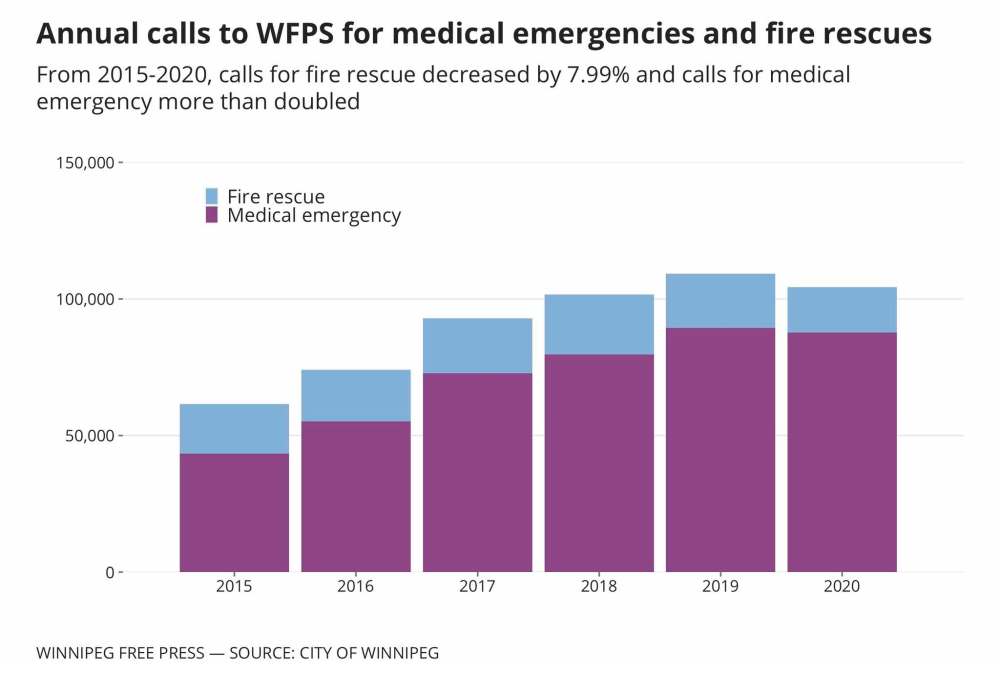

What those long-term trends mean is firefighters are keeping busy attending medical calls. That’s because from 2015 to 2020, according to city data, fire calls decreased by an additional 7.99 per cent, while calls for medical emergencies increased by 101.96 per cent.

Despite the significant decrease in fire calls and the spike in medical calls, Lane has previously said that the declining number of fires is not a reason to staff fewer firefighters. In fact, Lane pointed to high utilization rates of ambulances as “what actually drives the efficiency of our model.”

“We bring every resources out of them that we can. We use them heavily,” he said.

● ● ●

Twenty-three years after Richardson submitted his master’s thesis to the University of Winnipeg and changed the face of emergency services in the city, another local first responder submitted her thesis at the University of Manitoba.

Last April, Jennifer Setlack, who spent 11 years at the WFPS as a primary-care paramedic, submitted her thesis to the U of M’s department of sociology and criminology, entitled: “Winnipeg’s Reliance on Emergency Services and the Firefighting Exception.”

In her thesis, Setlack showed that not only have fire and paramedic costs exceeded inflationary growth, but that emergency services — both for the WFPS and the Winnipeg Police Service — comprise a staggering 45 per cent of the total tax-supported operating budget in the city.

There are 36 WFPS stations throughout the city, with the busiest located in the downtown core. While the number of fires has been falling precipitously in recent years, firefighters often point out that Winnipeg still sees more blazes than many other large Canadian cities.

But Setlack argues that decreasing fires in Winnipeg — which is consistent with broader trends seen across the country — means that fire trucks often sit idle, and when they are in use, it’s largely to respond to medical calls, not fire emergencies.

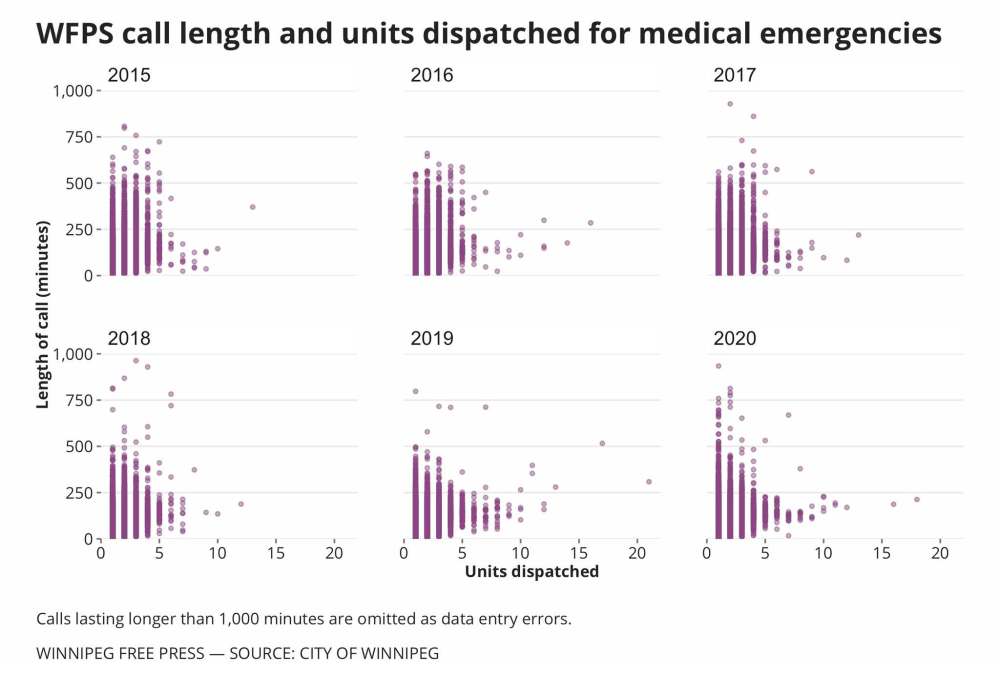

This is supported by WFPS availability data cited in Setlack’s thesis. City fire trucks were available 88.39 per cent of the time in 2015, 87.84 per cent in 2016, 88.83 per cent in 2017, 88.25 per cent in 2018 and 88.16 per cent in 2019.

“Simply put, fires have decreased by 46 per cent over the past 10 years, meanwhile medical services demand has increased…. Arguably, Winnipeg does not need as many firefighters or fire halls as it has in past years,” Setlack wrote.

Winnipeg has created a crisis partially of its own making, according to Setlack, who said disinvestment in community wellness and social supports has resulted in increased reliance on emergency services to fill social needs that are not being met.

“This creates a cycle of increased demand for police and paramedic services, followed by frequent funding increases to these departments,” she wrote.

To highlight this, Setlack points to past comments from WFPS deputy chief Christian Schmidt, who in December 2019 spoke about a critical shortage of ambulances. For more than seven hours that month, there were no ambulances available to send to medical emergencies.

Despite significant increases in the number of medical calls and the declining number of fires, the WFPS has not invested in ramping up capacity on the paramedic side of the department. According to Setlack, no additional ambulances or staffing have been added to EMS operations since 2011.

That’s consistent with complaints heard during interviews with paramedic sources. One, associated with the paramedics union, said the current situation is the result of the UFFW “trying to keep their membership up at a time when fires aren’t happening.”

“Paramedics watch all the investment that happens in fire and go, ‘(the vast majority) of calls are medical calls. Why are you buying new pumper trucks? Why are you expanding new stations? Why are you doing that? Why isn’t there investment on the paramedic side?” – Paramedic

“Paramedics watch all the investment that happens in fire and go, ‘(the vast majority) of calls are medical calls. Why are you buying new pumper trucks? Why are you expanding new stations? Why are you doing that? Why isn’t there investment on the paramedic side?” the source said.

“The answer you would get from most paramedics is, ‘They need to keep investing in fire. They need to have those people going to medical calls to justify all of the expenditures.’”

Setlack is more scathing in her critique, arguing a “politically capacious firefighting union” has seized upon the neglect of social health in Winnipeg and sacrificed the “greater public good” to its own “opportunistic growth strategy.”

“Although there are many benefits of unions to society, at this historical moment, there is an inverse relationship of UFFW strength and the public good…. The agential role Forrest plays means that the UFFW has been able to amass outsized political power in Winnipeg,” she wrote.

“The key message is that UFFW’s influence over public decisions, through disproportionate lobbying power and its ability to impact politicians, creates a situation where it is nearly impossible to have an informed, evidence-based approach to the future of emergency services.”

The UFFW did not respond to a request for comment.

During her 11 years working full time for the WFPS as a primary-care paramedic, Setlack earned undergraduate degrees in science, with a major in biological sciences, and in arts, with a double major in psychology and sociology.

In her resignation letter sent to top WFPS brass in July 2020, Setlack wrote that she had always intended to remain working for the department and wanted to use her education “to do valuable research and get involved in creating department policy.”

“However, the department senior management leadership team has made this impossible and virtually intolerable for me to stay,” she wrote.

● ● ●

In the aftermath of the racism allegation going public, Mayor Brian Bowman called upon Forrest to publicly acknowledge that systemic racism exists within the department and his union.

In response, Forrest issued a press release, in which he did not acknowledge the existence of systemic racism in the WFPS or the UFFW, but did say that racism, be it implicit or explicit, is a “very serious issue.”

It was the first time Forrest had broken his silence on the ongoing controversy. He vowed the union would defend the firefighters at an upcoming hearing, adding they had been “tried and convicted before the full facts were dealt with.”

While it’s not clear what defence the union will offer, two firefighters who spoke to the Free Press complained the third-party consultant tapped by the city to conduct the review into the incident was in a conflict of interest.

According to the firefighters, the same firm has also been contracted to roll out upcoming anti-bias training at the city. They allege that incentivized the investigator to find “implicit racial bias” on the call.

The city said the firm Equitable Solutions was hired last fall to investigate the allegations of racism on the call. At the same time, the city was “exploring options” for a workplace culture assessment in the department.

Equitable Solutions has been hired to lead two sessions of mandatory training — one for the city’s senior management team and one for mayor and council.

Meanwhile, the workplace culture assessment will be primarily conducted by MNP. But since MNP’s survey “did not include a diversity aspect,” the city tapped Equitable Solutions to “offer a similar survey and a small sample focus group format to capture the equity, inclusion and diversity portion of the survey.”

“The results of the investigation had no impact on the decision to do this work. The work of MNP and Equitable Solutions is necessary to assist the city with understanding the issues impacting the WFPS department,” a city spokeswoman said in a written statement.

It is possible the UFFW will seize upon the conflict of interest allegation when it defends its members at the upcoming disciplinary hearing.

In a written statement, Lane said the WFPS is aware of the recent complaints in the department and the “workplace cultural issues that exist among employees.”

“For this reason, the WFPS has engaged third-party consultants to lead a workplace cultural assessment aimed at better understanding some of these issues, as they relate to the big picture of the WFPS’ workplace culture,” Lane wrote.

“This type of assessment has never been done before at the WFPS, and it is an important step forward for the department.”

The assessment will include surveys for employees to provide feedback and experiences about the state of the department. Lane said the WFPS is encouraging all members to participate honestly so they can get a clear picture of the current situation.

The third-party consultants will also host focus groups “aimed at better understanding the experience of WFPS members in more detail.”

“Every employee should feel valued, respected, and like they are part of an effective team. Once we have a better understanding of the current experience of our employees, we are committed to improving our culture in areas where there may be weakness, and celebrating the areas that are working well,” Lane wrote.

With regard to inadequate paramedic resources, Lane said that in late 2019 the WFPS submitted a report to Shared Health Manitoba detailing “stresses on EMS.” The city is contracted by the province to operate paramedic services.

The city asked for many additional resources including, among other things, at least eight new 24-hour transport ambulances and the replacement of five city-owned ambulances that have been decommissioned due to old age.

“To date, no response has been received,” he said.

A city spokeswoman said in a written statement that the “integrated fire, rescue and EMS system works well for Winnipeg.”

“We strongly believe the Winnipeg Fire Paramedic Service is best suited to continue providing Winnipeg citizens with world-class integrated-emergency medical services,” she said.

“Through the integrated model, the WFPS is able to ensure a paramedic is able to get to people who need help, as quickly as possible, whether they arrive on a fire apparatus or an ambulance.”

Meanwhile, the Manitoba Government and General Employees’ Union, which represents city paramedics, says it is pushing for an “urgent meeting” with Bowman and top city brass to discuss the state of the WFPS.

“For too long, a culture of racism, sexism, favouritism and discrimination has been allowed to continue within the WFPS. We have raised concerns about this culture in the past, and it is long past time for the city’s senior leadership to take decisive action to change it,” MGEU President Michelle Gawronsky said in a written statement.

“We continue to believe that the actions announced to date by the city are inadequate to deal with the seriousness of the problem. A staff survey and some training workshops are worthwhile, but on their own they will not fundamentally transform a culture that has allowed disrespectful, racist and discriminatory behaviour to continue without consequences.”

ryan.thorpe@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @rk_thorpe

Ryan Thorpe

Reporter

Ryan Thorpe likes the pace of daily news, the feeling of a broadsheet in his hands and the stress of never-ending deadlines hanging over his head.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Friday, February 12, 2021 7:11 PM CST: Corrects typo.

Updated on Saturday, February 13, 2021 9:58 AM CST: Fixes typo