Risky business Manitobans emerging from their COVID cocoons are facing the spectre of a new threat from highly contagious variants that could put the province right back in lockdown

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 12/02/2021 (1852 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

“We’ve been here before.”

It’s a new phrase Manitoba chief public health officer Brent Roussin has added to his repertoire of well-worn COVID-19 public health messages; it’s also one he’s been leaning on heavily as the province begins to roll back the punishing pandemic restrictions of the past three months.

This reminder, unlike the familiar calls to follow the fundamentals and stay home when sick, also serves as a sombre warning as people think about a visit to their favourite restaurant and getting back to the gym.

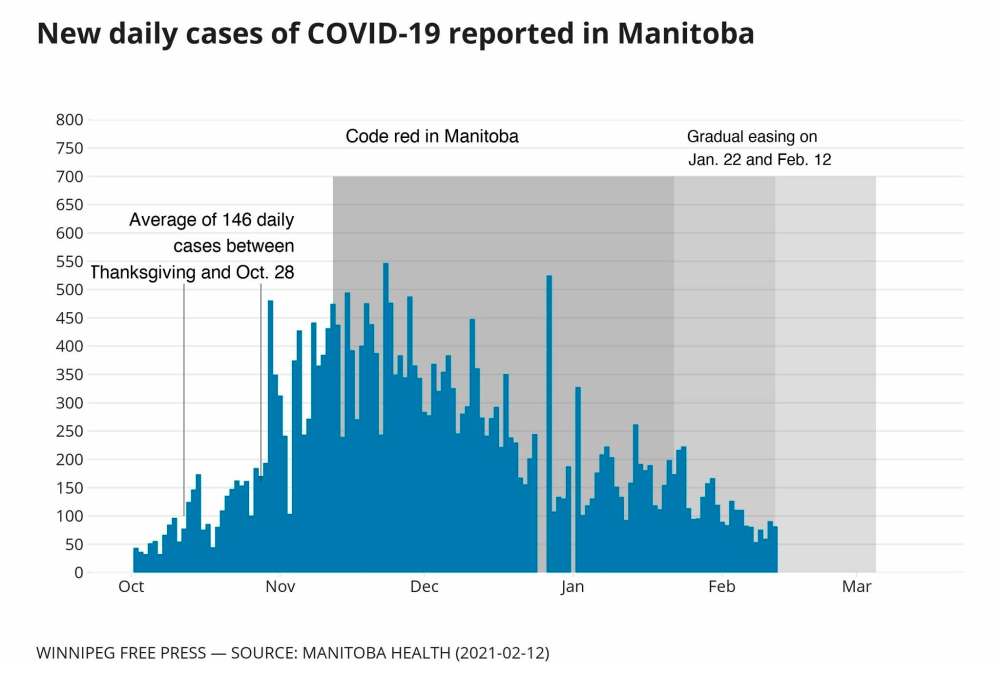

While Manitoba may have bent the pandemic curve after allowing it to climb to deadly and devastating heights through October and November — peaking at 593 new infections on Nov. 22 — the relative calm now being experienced in parts of the province could be shattered without warning.

“We can’t undo all of this hard work by simply opening everything up again. We have to remember that we’ve been here before,” Roussin said earlier this week, addressing the province’s plans to roll back restrictions. “If we open things up the same as we were in October, we will see November and December numbers.

“Nothing has changed since that time,” he said.

However, the COVID-19 outlook in Manitoba is different than it was in the fall.

Public health has made modest improvements to its testing and contact-tracing abilities and some vulnerable Manitobans and critical health-care workers have been vaccinated against the virus. But at the same time, more contagious variants have been detected in the country — including one case here — and the province’s intensive-care units are over capacity.

What remains the same is the threat the virus could rapidly spiral out of control, given the chance. it’s not clear what the province will do differently to prevent that from happening again.

Road to red

With the air carrying a chill, the leaves beginning to turn and school back in session for many Manitoba students, the coronavirus was quickly creeping through the populace in October.

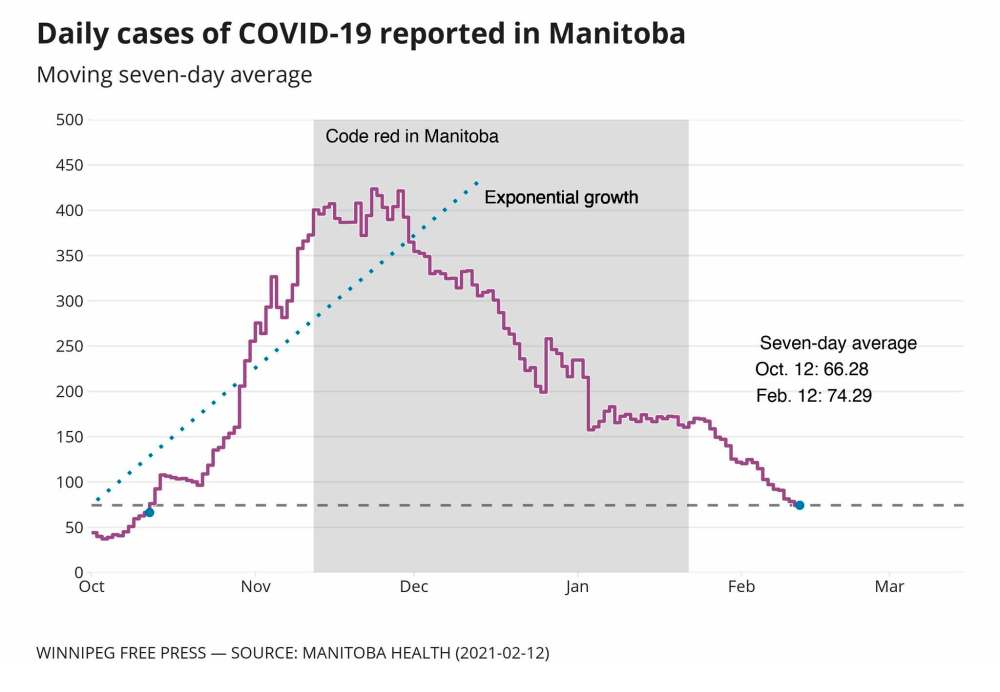

The province imposed code-orange public-health restrictions on Sept. 28. Between Sept. 29 and Oct. 13, Manitoba reported an average of 61 cases per day.

Further restrictions were added incrementally in the following days as more infections were reported in Winnipeg and nearby communities.

Public health was struggling to ramp up testing capacity and make the process of getting a swab less onerous. Contact-tracing efforts were being stretched by the volume of cases.

Following the Thanksgiving long weekend, Manitoba recorded an average of 146 cases daily until Oct. 28.

“What we’re talking about here is the great mystery of exponential growth,” said Raywat Deonandan, an epidemiologist and associate professor in the faculty of health sciences at the University of Ottawa.

“And It’s something that the human brain is not well wired to think about reflexively. It requires conscious effort to digest.”

Deonandan said the serious threat an infectious disease such as COVID-19 poses to spread rapidly through a population may not be immediately apparent, so public tolerance and buy-in of prevention orders, and political will to act, can fall short.

“The second you have exponential growth you should start to worry, and by the time you see things looking dire, it’s too late to have tepid responses,” he said. “As a result, if public-health interventions don’t feel like overreactions, they’re not enough.”

Prolonged circuit breaker

As new infections showed little sign of slowing, Roussin declared Winnipeg would move to critical-level code-red on the pandemic response system on Nov. 2.

Much like the restrictions in place today, the switch to code-red reduced the number of people allowed at cultural and religious gatherings. Retail outlets and gyms were capped at 25 per cent capacity, sports and recreation programs were suspended and casinos and VLT lounges closed. Bars and restaurants were forced to suspend in-person service.

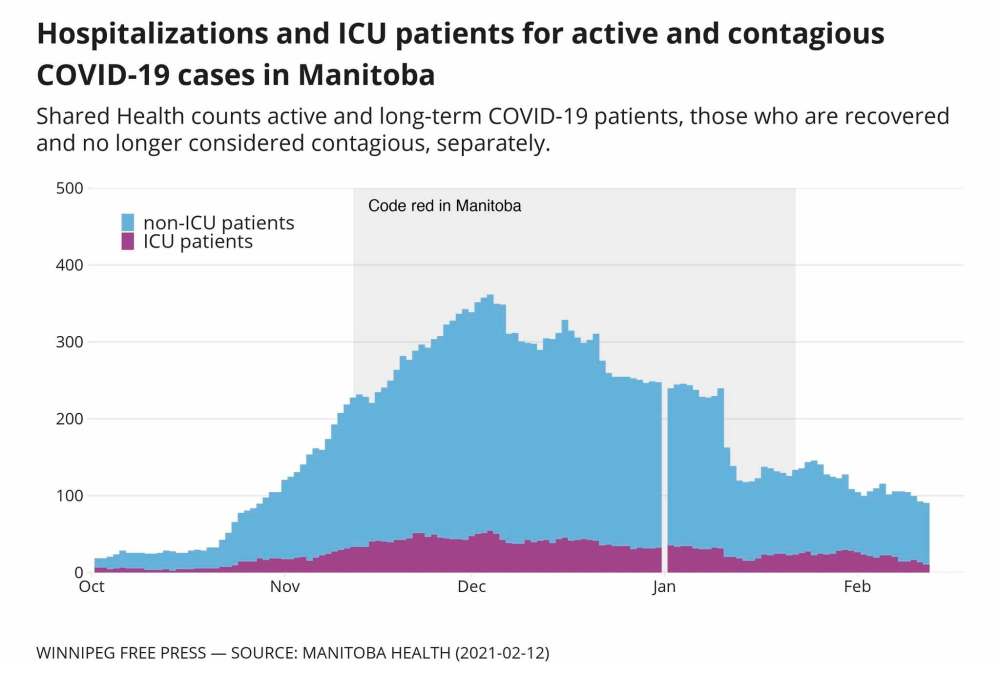

Cases continued to swell. The two weeks leading up to the imposition of strict code-red restrictions on Nov. 12 saw an average of 332 new infections a day. Hospitalizations more than doubled from 104 to 227.

Roussin said the “circuit breaker” lockdown, a short, sharp intervention meant to break COVID-19 transmission chains, would be in place for four weeks, adding public-health officials did not expect to see a dramatic increase in cases in the Winnipeg area.

When considering the lengthy code-red lockdown, Deonandan said it can be helpful to think of the COVID-19 spread in Manitoba as a semi-trailer barrelling down a highway.

“When you get to that speed, you can slam on the brakes but it’s still going to skid for a long time,” he said. “A circuit breaker lockdown is slamming on the brakes, but the more momentum the truck has, the longer it’s going to (take to) slow down.

“The longer you wait, the longer it’s going to take to reverse course.”

Ultimately, the circuit breaker would persist for 10 weeks, with restrictions and enforcement bolstered throughout. The province has recorded more than 24,000 cases, 1,000 hospitalizations and 704 pandemic deaths since Nov. 12.

Third wave?

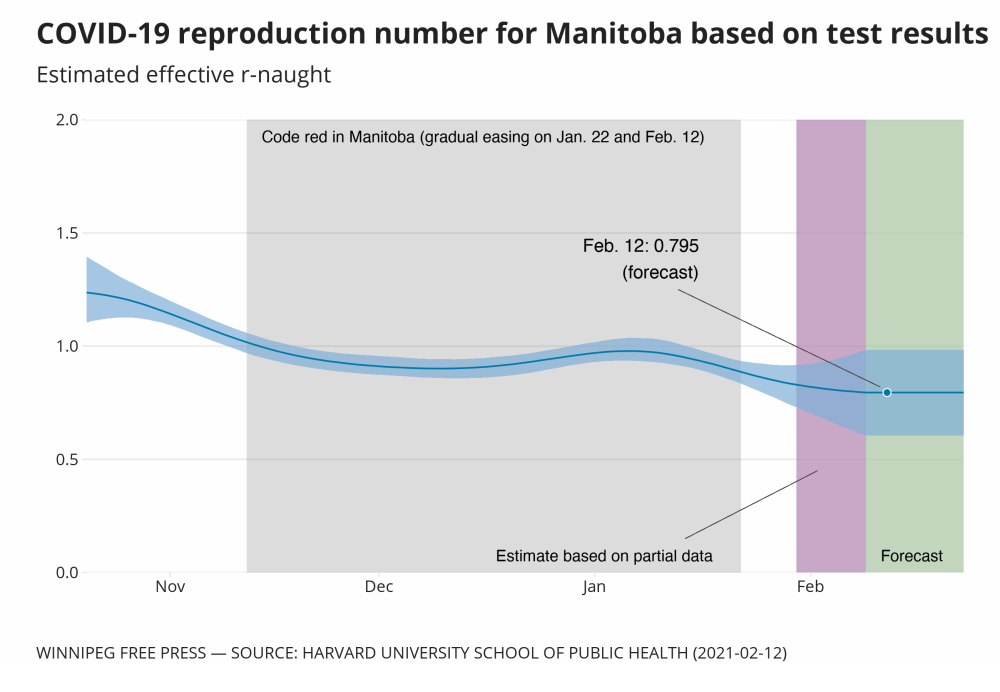

Three weeks into the province’s second economic reopening, public-health officials say they haven’t seen a marked increase in cases that can be tied to the slight easing of restrictions on Jan. 23 and there is cause for cautious optimism.

However, the average daily case count over the past two weeks exceeds the average in early October, driven in part by outbreaks in northern Manitoba, with test-positivity rates still high at about five per cent.

Manitoba has reported an average of 95 infections a day since Jan. 30, despite having tougher restrictions in place compared to early fall.

Dr. Jazz Atwal, acting deputy chief public health officer, has told reporters the province will reopen in three-week increments to monitor for increased cases as restrictions are eased.

On Wednesday, Atwal was unable to say how fast public health predicts cases to rise as the number of community contacts increase, nor could he say how much COVID-19 transmission the province can tolerate without seeing exponential growth.

“Realistically we have an idea of where cases might end up going, but it’s all going to be based upon how Manitobans behave,” he said. “It’s how we behave when we go to that restaurant now, it’s how we behave when we invite someone over.

“It’s going to be based on those interactions.”

Manitoba has not shared its pandemic projections for the most recent public-health orders, or the possible introduction of the B.117 variant — which is more transmissible and expected to quickly overtake circulating strains — in the community.

“There’s no absolute number where we hit this point we’re going to run into a lot of trouble,” Atwal said.

“Obviously, we have people in hospital right now, we have people in ICUs right now. If we see a general increase, a trend up, we’ll have to relook at that information, relook at the data, and see what needs to be done, or can the system manage that.”

Before pulling back restrictions, public health should ensure it can perform forward and backward contact tracing, isolate and support cases and contacts and introduce strategic asymptomatic surveillance using rapid tests, Deonandan said.

A Free Press request to interview a senior leader in the province’s contact-tracing efforts was not met by deadline.

It’s critical for public-health units and governments to determine thresholds that would trigger interventions based on the local context, Deonandan said, adding that metrics provided by institutions such as the U.S. Centers for Disease Control may be too generous for most Canadian jurisdictions.

“Now the caveat: the second your contact tracing can’t keep up, that’s the time to pull the plug,” he said.

Public health must also be prepared to detect and respond to new coronavirus variants, which could drive a third wave in late spring, he said.

“So that’s a whole new complication that lowers the threshold for action across the board,” he said. “And again, with that in mind, probably the only two solutions are COVID-zero (keeping transmission rates and cases as close to zero as possible) and mass vaccination.”

Jason Kindrachuk, Canada Research Chair in molecular pathogenesis of emerging and re-emerging viruses, said a sudden resurgence of COVID-19 remains a risk and it’s difficult to know what restrictions can be relaxed without causing a spike in cases.

“The big tell is going to be the next few days, what happens with B.117,” Kindrachuk said. “That’s the one I think is a wild card because of how quickly that virus is able to spread and how quick the doubling time is. We need to be acutely aware of where cases are and how quickly they are growing.

“We have to ensure that we are able to meet the demands of additional cases if and when they arise.”

And based on Manitoba’s daily case counts and hospital capacity, Deonandan said the numbers are probably still too high to justify further reopening.

“While you’re trending in the right direction, and it’s tempting to want to salvage the economy by opening things up… it strikes me that the risk of premature opening, as everybody knows, is the yo-yo effect,” he said. “You’ll just have to do it again.”

danielle.dasilva@freepress.mb.ca