‘We’re really failing our seniors’ Former MP Glover signs on as aide at Manitoba care home

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 05/02/2021 (1862 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

She’s a former city police officer and member of Parliament who served in Tory prime minister Stephen Harper’s cabinet. Now, in the midst of the COVID-19 health crisis, Shelly Glover is working as an uncertified health-care aide in a southern Manitoba personal care home.

And she’s pulling no punches about conditions in such facilities.

In an interview this week, Glover said chronic, severe understaffing is wearing out nurses and health-care aides and depriving residents of adequate care.

“We’re really failing our seniors. I am so ashamed to see our seniors being treated this way,” she said.

Glover said Manitoba Premier Brian Pallister should have boosted funding a long time ago to ensure adequate staffing during the pandemic.

“I’m so mad at Pallister. Where is the money that should have gone into the personal care homes? They were the targets of this stupid virus. We knew this for months — for a year, we’ve known this. Why are there no staffing increases?”

A request to speak Friday with Health Minister Heather Stefanson about staffing issues at personal care homes and related issues was declined.

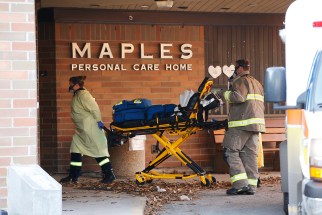

Glover, 54, said she was motivated to roll up her sleeves and get directly involved in seniors care after last fall’s Maples care home tragedy in Winnipeg, in which 56 residents died of COVID-19. She said she also wanted to make sure her mother-in-law, a care home resident in the Southern Health region, was properly cared for.

She took a five-day course for uncertified health-care aides offered by Red River College, in partnership with Shared Health, to relieve staff shortages during the pandemic. (The course for regular health-care aides is about 20 weeks in length.)

Glover was willing to work as a volunteer, but was told she couldn’t, due to pandemic response protocols.

“The province didn’t have to pay me, but only if I took the money could I help.”

Glover completed her course Dec. 9, and expected Shared Health to place her immediately. Despite numerous calls and emails, she said, she never received a care home placement.

Micro-credential program

The Manitoba government established an uncertified health-care aide micro-credential program in partnership with Red River College in November, to help ease staffing shortages in personal care homes caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Successful applicants take a five-day course, divided between online and hands-on training.

The Manitoba government established an uncertified health-care aide micro-credential program in partnership with Red River College in November, to help ease staffing shortages in personal care homes caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Successful applicants take a five-day course, divided between online and hands-on training.

Placements are based on the needs of the health regions and not on an applicant’s personal choice or connection to a particular site, a spokeswoman for Shared Health said in an email. “Communication with sites is ongoing to assess needs and determine appropriate… placements at facilities.”

Winnipeg has been identified as having the greatest need for the trainees, with a lesser demand in the Southern Health and Interlake-Eastern regions, she said.

Some 114 uncertified health-care aides have been deployed in the capital city, while 34 have accepted positions in Southern Health and nine in Interlake-Eastern.

Most of the positions were filled by graduates of the new program, although a few dozen positions have been filled by individuals whose skill set allowed them to be deployed directly without completing the training, the province said.

The Shared Health spokeswoman noted family access to personal care homes has continued throughout the pandemic.

Designated family members are eligible to provide care and support to their loved one “as an important member of the care team.”

Glover and two fellow classmates wound up finding work at a southern Manitoba centre, which she declined to name, by applying directly to the facility.

That was four weeks ago. Her mother-in-law died Dec. 22.

The former Winnipeg Police Service sergeant and seven-year MP for Saint Boniface said she’s had her eyes opened to conditions inside personal care homes.

“These poor seniors — we wake them up, we change them, we feed them, we put them back in the room. There’s no interaction. Quality of life has been reduced because there aren’t enough staff to do the basics,” Glover said.

Due to staff shortages, residents are awakened as early as 5 a.m. so all can be readied for when breakfast is served at 7:30, she said. “It’s supposed to be their home. It’s not supposed to be an institution.”

Staff are constantly being asked to work double shifts, she said.

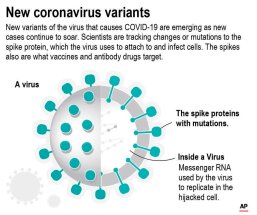

Personal care home advocates have long-complained about staffing shortages, and COVID-19 has exacerbated the problem as staff have frequently had to self-isolate for days while awaiting the results of tests or spend longer periods away after becoming infected.

Another woman who took the same program as Glover and also works in a Southern Health care home said she’s had to continually turn down requests for additional shifts because of other commitments.

“I could be working 80 hours a week if I wanted,” said the woman, who asked her name not be used.

Glover said she is frustrated the uncertified health-care aide micro-credential program appears to be under-used. She and others have faced long waits for placement — if they receive them at all — at a time when care homes need all the staff they can get.

“These poor seniors– we wake them up, we change them, we feed them, we put them back in the room. There’s no interaction. Quality of life has been reduced because there aren’t enough staff to do the basics.” – Shelly Glover, former MP

Under the program, which was launched in November, successful applicants are paid about $750 after taxes to take the five-day course. In return, they must agree to work at least two shifts per week for three months.

The province says the demand for the health-care aides varies from one region to the next, with the greatest need in Winnipeg.

In a brief statement, a spokesman for Stefanson said Friday the health minister is satisfied with the outcome of the uncertified health-care aide program so far.

larry.kusch@freepress.mb.ca