On guard against COVID-19 variants So far, no mutations have surfaced in Manitoba. Here's how to keep it that way.

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 05/02/2021 (1858 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Highly contagious variants of COVID-19 are emerging from every corner of the globe. People can take steps to remain safe and prevent Manitoba from unleashing its own mutation of the novel coronavirus.

Here are answers to some questions asked by our readers:

1) Why didn’t I hear about these variants last year?

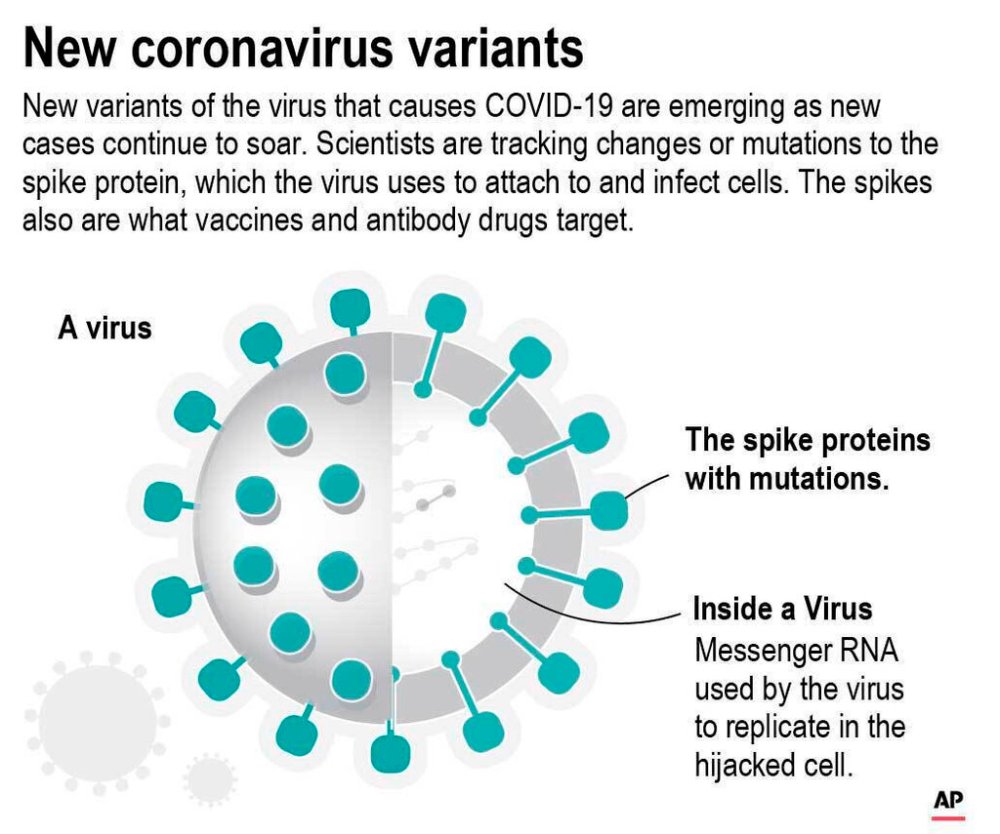

Viruses infect cells, and use them to replicate more viral particles, which a human or animal can subsequently transmit to others. Errors can emerge in genetic codes during this copying process.

A virus such as influenza mutates enough that it requires a new flu shot every year.

The novel coronavirus is a lot more stable. In the first wave of COVID-19, small variations could indicate where cases came from. For example, the main strain in Italy was slightly different than the strain in Wuhan.

Every new host presents an opportunity for the coronavirus to mutate — and there have been a lot more hosts.

Some pathogens mutate more frequently in people who have weak immune responses. That’s because the particles are under attack, but not enough to stop finding ways to replicate. Coronaviruses can jump between species such as humans, minks and bats, which might introduce more chances for mutation.

This is why most experts advise against trying to achieve herd immunity through widespread infections. Mutations create the possibility the virus will re-infect people who had been considered immune.

Since fall, there’s been a huge rise in cases worldwide and there have been enough mutations that some have changed how the coronavirus spreads. Officials often call these ones “variations of concern.”

2) Why are these variants more contagious?

The three variants that have taken hold in Britain, South Africa and Brazil involve mutations to the part of the coronavirus that latches onto cells, known as a spike protein.

A COVID-19 vaccine, or prior infection, trains the body to detect the spike protein, and tackle it early on. But the immune response might take longer to recognize a spike protein with a different shape, at which point the virus could already be replicating inside the body.

The main approved vaccines still appear to be highly effective against emerging strains. Moderna is working on a booster shot in case people need a third shot to maintain immunity against new variants.

Mutations aren’t necessarily more deadly; evolutionary biologists believe viruses tend to mutate toward a less deadly version, so that their hosts keep spreading the virus.

3) What are the main variants so far?

The B.1.1.7 variant, which has taken hold in the United Kingdom, appears to be 30 to 50 per cent more transmissible, with a spike protein that does a better job of binding to cells.

This so-called U.K. variant had shown up in 242 cases in Canada as of Friday.

The B.1.351 variant, which is the dominant version of the coronavirus in South Africa, seems to be the most troubling.

In laboratory tests, it appears to somewhat thwart both the immune system and vaccines, though research continues and the situation might not play out in real life.

In Canada, there were 13 documented cases of the variant associated with South Africa.

The B.1.1.28 variant, associated with Brazil, hasn’t been detected in Canada yet.

The Brazilian city of Manaus had so many COVID-19 infections during the first wave that officials presumed the region had herd immunity, until a new variant emerged that appears to have reinfected many people who caught COVID-19 in the first round.

4) Are there any variants in Manitoba?

None has been confirmed to date.

The current practice in Manitoba is to sequence the genome of about five per cent of positive COVID-19 samples.

That translated to 1,434 samples from March 2020 to mid-January of this year, though only 1,169 were of a sufficient quality to be analyzed.

Sequencing involves breaking down a sample into tens of thousands of pieces and then analyzing various parts, which takes about two weeks.

5) Why doesn’t Manitoba check all COVID-19 samples for variants?

Sequencing is a surveillance tool used by researchers to get a sense of what strains of viruses, such as the flu, are circulating.

That’s unlike diagnostic tools, which indicate when someone is infected. Those are in such high demand that companies have developed numerous tests with a range of speed and caseload capacity.

Sequencing requires training, immense computing power and about two weeks to get a single result, which can cost hundreds of dollars.

A Health Department spokeswoman said the five per cent of positive COVID-19 tests that Manitoba performs in just one week “is approximately equivalent to the entire output of (data processing at Cadham Provincial Lab) in a year.”

Manitoba’s output is on par with other provinces, though Ontario and Quebec have plans to double their sequencing.

In addition, provinces such as Alberta do batch-testing through less specific, diagnostic methods. That means checking hundreds of samples within hours for any mutant strain that could alter the spike protein — instead of the weeks it takes to do sequencing and determine which specific variant is involved.

6) What do I need to do?

Be more vigilant. After almost a year into this pandemic, everyone is tired. Officials say the fundamentals — keeping distance, washing hands, and wearing masks — are the best defence.

Public Health Ontario has suggested a looser criterion for deeming someone a contact of a COVID-19 case, which is currently restricted to people who interact for 15 minutes. It believes anyone without a medical grade mask and eye protection could be at risk of catching the virus, even in a shorter interaction.

Manitoba and federal officials have resisted changing their guidance.

“With a more transmissible virus, people do have to pay much more attention and be adhering to the tried-and-true public health measures,” Dr. Theresa Tam, Canada’s chief public health officer, said Friday.

“If you’re in an area where there could be community transmission with a variant, the bottom line is you need to stick to the fewest interactions, with the fewest people, for the shortest time, at the greatest distance possible.”

Following those rules will help keep you safe — and lowers the chance of creating a Winnipeg variant.

Politicians and health officials are grappling with how to peel back restrictions, which successfully tamped down cases that stemmed from Christmas gatherings. Keeping restrictions in place wears down the public, but loosening them could help a more contagious variant outcompete the main strains that are circulating in Canada.

7) What about double-masking?

Canada’s current guidance is to try to use three-layer masks, ideally with a material called polypropylene. Originally, a single-layer mask was fine, but no longer appears sufficiently effective.

Germany recently mandated the use of masks with better protection, such as KN95 masks, in all public buildings, to prevent these highly contagious strains from taking hold.

While some people wear two masks, it doesn’t appear to be official advice in most countries. Some infectious-disease experts have suggested wearing a cloth mask on top of a surgical mask to create more layers to trap virus particles.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, who helps co-ordinate the U.S. response to COVID-19, said he often double-masks. “It just makes common sense that it likely would be more effective,” he said last week.

dylan.robertson@freepress.mb.ca

History

Updated on Saturday, February 6, 2021 2:39 PM CST: Fixes minor grammar error.