Putting joy on hold A baby is cause for celebration, but that happiness is tempered with a sense of loss for many new parents in a pandemic

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 05/02/2021 (1767 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Tess Klachefsky and Jordan Cieciwa were ready to have a baby.

They planned. They saved. They built their careers. They bought a house. They got married in June 2019 and Klachefsky was pregnant within weeks.

“And, wouldn’t you know it, the world was like, ‘Hey, guess what — here’s a pandemic,’” says Cieciwa, 40, with a laugh.

Betty, their daughter, was born on March 25 at St. Boniface Hospital, just shy of two weeks after Manitoba declared its first case of COVID-19. Their experience has been nothing like they expected and nothing they would have chosen.

“I was really scared,” says Klachefsky, 33, of when the pandemic hit. It was another blow: Klachefsky was at the end of a rough pregnancy and was grieving the loss of her mother, who had died in November 2019. In the weeks following Betty’s birth, the world was shut down, leaving Klachefsky isolated with her grief and a new baby.

“My mom would be the person that I would turn to to help me navigate any situation — especially motherhood,” she says.

● ● ●

“There’s no good time to have a baby” is something people like to say. But having a baby during a global pandemic is especially fraught.

The loneliness of solo ultrasounds. The excruciating feeling of being told by your fertility clinic you have to wait some more after you’ve already waited for so long. The sadness of grandparents who have yet to hold their grandchildren. The disappointment over cancelled celebrations, rites of passage unmarked. The fear of a virus.

Even during the best of times, becoming a parent is a life-altering experience that comes with a roiling stew of emotions. Parents have always had to navigate a new normal; it’s a whole new world when someone is born. Pregnant people and parents of newborns often feel shame and guilt for feeling any emotion that is not heart-bursting joy — or for feeling disappointment that their pregnancy and birth didn’t look the way they wanted it to.

“People have different expectations, and they’re not always met. Birth can be beautiful and magical and all of those things– but it can also be stressful and it can also be traumatic.” — Erin Bockstael

“Our programming really strives to validate and affirm and acknowledge those feelings because really, that’s such a reality in pregnancy and birth,” says Erin Bockstael, a team leader in the Mothers Program & Health Promotion at Women’s Health Clinic. “People have different expectations, and they’re not always met. Birth can be beautiful and magical and all of those things — but it can also be stressful and it can also be traumatic.”

Becoming a parent can already be anxiety-provoking — “it’s a brand new job that you have no training for, and it’s one that you’re particularly invested in doing well,” as Bockstael puts it — but the pandemic has heightened feelings of worry and uncertainty.

In one program, participants do an exercise called I’m OK If. “And we go through all those feelings. Like, I’m OK if I feel sad, if I feel empty, if I feel disappointed, if I feel anxious, and we talk about, are we OK? And how can we support ourselves maybe feeling closer to OK? And what are the things I can reach out for if I need more help if I’m not OK?

“There’s like a social script people feel they need to follow, which is, ‘I have a healthy baby, so I can’t complain’ kind of thing,” she adds. “But it’s not complaining to name what you’re feeling.”

Klachefsky would agree with that sentiment.

“I think we have to be careful about doing the, ‘Well, at least I don’t have it as bad as so-and-so’ or ‘It’s not as bad as it could be,’ because I think that can really be a way to silence people and invalidate their struggle,” she says. “Because yeah, it could always be worse. But that doesn’t mean that what somebody is dealing with isn’t really hard.”

One major frustration Klachefsky encountered was not being able to access the material supports she needed. “I had a really hard time breastfeeding Betty at first. And the public health nurse came twice, but what I really needed was a lactation consultant, and I didn’t have access to one unless I went to a clinic. And I was too scared to go to a clinic.”

Ten months on, Klachefsky is grateful for her “chubby, healthy, happy baby,” as well as “a really great partner who is just as much of a parent as I am” — but it’s been a hard time.

For Cieciwa, Betty’s arrival dovetailed with a job loss owing to the pandemic. Now, he’s embracing a new identity as a stay-at-home parent.

“My dream in life was never to be a stay-at-home dad, but the situation the pandemic’s created, it looks like that will be what I’m doing for the next couple of months. I am loving hanging out and watching her do everything, and feeling like I’m part of her learning experience.”

But the lack of community around them has been difficult. When Klachefsky got pregnant, they were excited about sharing experiences with friends who were also expecting, and getting out and taking their daughter places.

“It was like, ‘Oh, this is gonna be so great. We can have all these times together and yada-yada-yada,” Cieciwa says. “Now, it’s just Tess and me versus the world.”

● ● ●

This may have been Cyara Bird’s third pregnancy, but it was her first time being pregnant during a global pandemic.

Bird, 24, lives in Little Black River First Nation, on the eastern shores of Lake Winnipeg, with her husband Gabriel, their daughters Wya, 4, and Wrenley, almost 2, and their new son, Larson, who was born in Oct. 22.

She was early in her pregnancy when the pandemic began, and was nervous about how COVID-19, then much less understood, might affect the health of her baby. “I became a germaphobe,” she says via email. “Most mothers have this fierce instinct to protect their babies, earth side and in the womb. Even to this day I obsessively sanitize, wash my hands and feel the need to shower before holding my son after I’ve been out shopping.”

Bird had a scary complication early in her pregnancy in which her placenta partially detached. Her hCG level had dropped, which can be a sign of miscarriage.

“My husband couldn’t even be with me in the room (at the Selkirk Regional Health Centre),” Bird says. “He had to wait in our vehicle. I had to text him to tell him I might have lost our baby and that was one of the most empty feelings I have ever experienced.”

Bird was put on bedrest, and her husband continued to have to wait in the car during appointments.

“He missed out on so much of my pregnancy and that’s time he will never get back,” Bird says. “He didn’t get to see his only son’s first wiggle on the ultrasound, he didn’t get to hear Larson’s heartbeat until I was in labour. I know how much it hurt him to not be able to see all of those firsts. It was hard on me, too, especially with the complex complication I had, every appointment was precious because I never knew if it would be my last.”

With a December due date, Katie German, 37, was pregnant with her second son, Jasper, for the whole pandemic. Felix, her firstborn, is 5.

“It was a nice focus to have, as opposed to just freaking out about the pandemic,” she says, feeding her five-week-old during a Zoom call. “It was much different pregnancy than our first one. Our first one was by the book, super easy, no issues whatsoever. And this one was like, totally off the map, very different.”

German says that first ultrasound was terrifying. “I’m just sitting there by myself with an ultrasound technician, hoping that nothing was going to be said that I wouldn’t be able to handle.”

Like Bird, German says one of the biggest challenges was that her husband, Travis Wiess, was not able to be at any ultrasounds or appointments. “He’s a part of it too, right?” she says. She took a sneaky video of a subsequent ultrasound with her phone, but it wasn’t the same.

Accessing a human to talk to was another challenge, German says. “There were a couple times that things came up, and the go-to is ‘call Health Links’ — but Health Links was, at times, just crazy amounts of time waiting.”

Still, being pregnant during a pandemic came with unexpected silver linings. German works in theatre and, in normal times, she’d be busy. “There’s never a good time to (be pregnant), unfortunately, because there’s always shows and there’s always auditions. So having sort of a pocket of pause was really lovely.”

Jasper was born on Dec. 16. Wiess is working from home, and having him around during the first few weeks of their son’s life has also been a gift. In normal times, being at home alone with a newborn can be incredibly isolating. “You’re by yourself, and so you need to have people come and see you or you need to go visit people.”

In addition to navigating her first pregnancy during a pandemic, Andrea Tiwari, 31, was also dealing with the stress of running a restaurant — Tiwari is owner/chef at Bindy’s Caribbean Delights in the Forks Market — and, like Klachefsky, grieving the loss of a parent. Her father, Bindra (Bindy) Tiwari, died last August.

“It’s been a crazy year,” she says via FaceTime while her four-month-old son, Louie, who was born Sept. 29, naps. “And I have to say, though, Louie has brought so much joy to that sadness in my life. The grieving process of a parent is very, very hard. And I’m just so blessed that I have Louie here now with me to keep me focused on something good.”

● ● ●

In the early days of the pandemic, people joked that lockdowns would result in a baby boom, ushering in an entire generation of “coronials.”

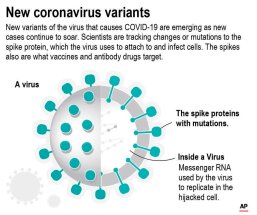

The first wave of babies who were conceived during the pandemic only started being born in the past several weeks, so it’s a bit early to attach numbers to this claim. Still, fertility and economic experts are saying the coronial baby boom is looking more like a baby bust — especially in the pandemic-ravaged United States.

One thing is certain: pandemic or no, babies are still being born, every day. And Dr. Leslea Walters helps bring them into the world.

Walters is an obstetrician-gynecologist who practises out of Millennium Medical Centre and delivers at the Women’s Hospital at Health Sciences Centre. In December 2020, the first month of “coronial” baby births, Walters says hospital births — at both St. Boniface and HSC — were down by 100 compared with December 2019. In January 2021, there were 150 fewer hospital births compared with January 2020.

When COVID-19 arrived in Manitoba in March, it was a time of anxiety for her obstetrical unit, she says. They were hearing grim stories out of hard-hit places such as New York City and Italy, and weren’t sure yet how hard Manitoba would be hit and how it would affect them.

“Obstetrics is, in our minds, a very specialized part of medicine,” Walters says. “You can’t just pull a nurse from anywhere, you can’t just pull a physician from anywhere to provide obstetrical management without hugely affecting outcomes.”

After about three months of working in a rotation, they were able to get back to something resembling normal with added personal protection equipment. Walters says they have been able to maintain a support person for women in labour, even through the strictest hospital shutdowns.

“There have been people who were positive with COVID and were sick, who were not able to have a support person with them. And it’s been a very small number, but we all hate it. The patients hate it. The nurses hate it. The doctors hate it. It’s terrible.”– Dr. Leslea Walters

“Generally speaking, every healthy woman coming in having a baby has their supportive partner with them,” Walters says. “But there have been people who were positive with COVID and were sick, who were not able to have a support person with them. And it’s been a very small number, but we all hate it. The patients hate it. The nurses hate it. The doctors hate it. It’s terrible.”

Still, there are positive upshots to the restrictions: not all family members are supportive in the delivery room, Walters points out. Some patients have told her it’s a relief to have that decision taken away from them.

And as for labouring and delivering in a mask, it hasn’t been as big an issue as she expected. Many patients are concerned about the health of those caring for them.

“Women are warriors,” Walters says. “So it doesn’t surprise me that women are able to labour and deliver with a mask on. We see women at the height of their strength and resilience every single day. They just take it in stride. It’s amazing what women can do in the midst of this whole thing.”

German, Bird and Tiwari all gave birth at the Women’s Hospital at HSC within months of each other.

“I felt so taken care of and heard, and anytime I was nervous about something, they took the time to actually sit down and talk to me about things. I didn’t ever feel on the sidelines or like that I needed to be rushed through,” German says. “I just think that was really cool, especially with everything that they’re dealing with right now.”

“The nurses and doctors were so amazing and did their absolute best to support both my husband and I,” Bird says. “It was hard not being able to see my mom and have her there when I was giving birth, but the nurses and doctors did just such an amazing job being compassionate, patient, and they were just so supportive. It was my best birth by far.”

Tiwari was alone in triage until she was about four to five centimetres dilated. “It was kind of scary because I was exhausted, I was in pain. I just wanted (my fiancé) to be there to hold my hand or rub my back, and he was out in the waiting room.”

But once things progressed, her fiancé, Nelson Salazar, was allowed to join her in the delivery ward which, as it happens, is where his mother works.

“She actually delivered Louie,” Tiwari says with a laugh. “And so it was an extra-special moment. My fiancé was there. His mom was there. Like, what grandma gets to say, ‘I delivered my grandson?’”

● ● ●

Rory and Lisa McDonald will welcome their first baby in May 2021 and, for a while, they were worried neither of them would be able to be in the room for the birth.

The McDonalds are expecting via surrogate. A few years ago, Lisa, 30, had a cancer scare that led to having an emergency surgery to have her uterus removed. Because she still has her ovaries, Lisa and her husband Rory, 32, were able to do in vitro fertilization (IVF) — the process by which an egg is fertilized with sperm outside the body to form an embryo, which is then transferred into a uterus.

The uterus, in this case, belongs to a close cousin and friend named Sarah, who offered to carry their baby. In early March, they began the process at Heartland Fertility and Gynecology Clinic, the only fertility centre in Manitoba. Rory and Lisa felt like things were moving forward — and then the pandemic hit.

“We had thousands of dollars worth of drugs on our dining room table and we get a phone call from Heartland saying, ‘Stop, don’t take anything. We’re closing everything down because of COVID,’” Lisa says. “We had waited almost two years for that moment.”

They were delayed almost two months. Owing to COVID-19 restrictions, the couple could not be with their surrogate, either.

“That was really, really difficult,” Lisa says. “It was already hard that we had to do (surrogacy) in the first place, and now we had to do it alone. We weren’t allowed to be with Sarah.”

The three of them would have been at the embryo transfer; instead, they FaceTimed with Sarah afterwards. “You just felt disconnected,” Rory says. “I mean, even more disconnected, because it’s already not Lisa’s body.”

The embryo transfer was successful, but the couple’s excitement has been muted. Public health restrictions meant neither Rory or Lisa could attend those first ultrasounds and appointments. It’s standard, in a surrogacy, to have an agreement drawn up by a lawyer between the biological parents and the surrogate. Per their agreement, one parent must be able to be at appointments. Rory and Lisa ended up having to advocate for themselves, and their OB-GYN finally agreed to allow one of them to attend appointments. “Normally you wouldn’t have to do that,” Lisa says. “COVID led us to have to do these kinds of things.”

That hasn’t been the only stress. Their surrogate contracted COVID-19 early on, so not only were they worried for their cousin, they were worried for their baby. Everyone is healthy now.

And though the due date is still months away, it’s likely only one parent will be able to attend the birth. Lisa is struggling with that.

“It’s already such a sad process that, like, obviously we wish it was us and not having to involve a third person. We’re thankful we have a surrogate and all but still, it doesn’t seem fair,” she says. “How can someone, even a hospital, say, ‘No, you’re not allowed to be present at your child’s birth’ after all you’ve been through?”

Morwenna Trevenen, 38, and her husband, Kyle Collins, can relate to the fertility waiting game. The couple got married in 2013 and started trying for a baby immediately. What followed was seven long years of failed intrauterine inseminations, havoc-wreaking hormone treatments, painful procedures, disappointment and heartbreak — including an adoption in 2016 that was reversed 10 days later. She’s currently writing a book about her experience.

After taking some time to process that loss, Collins’ parents offered to pay for one round of IVF. “That’s the only reason that we tried it because we decided we were done and we couldn’t handle the emotion of it anymore,” Trevenen says. “And we were sick of hemorrhaging money, and we had to pay our mortgage.”

And so, they began the IVF process with Heartland in the months before the pandemic.

“Our last appointment in March was with our doctor over the phone because of COVID, and he gave us the news that of the five embryos we’d had, only one of them was going to be viable — and we couldn’t do anything because of COVID,” Trevenen says.

Trevenen had the embryo transfer done in July. The stakes were high — one embryo, one shot. But this time it was good news. Over the crackle of speakerphone, Trevenen and her husband finally heard the words they thought they may never hear: “Congratulations, you’re pregnant.”

“We just sort of stared at each other and not moving for a sec because we couldn’t process it,” she says. “We were so used to, for so many years, ‘I’m sorry, we’re gonna try again’ or I’m sorry, it didn’t work.’”

Their baby, a boy, is due at the end of March/early April.

“People are missing that connection and all those gatherings and rituals that involve being part of your community that help mark this transition. So things like baby showers or baptisms, blessingways, naming ceremonies– those all had to be reinvented, too.” — Erin Bockstael

Now, Trevenen is navigating the pandemic as a pregnant woman, dealing with the inconvenience of having to buy maternity clothes online during a code-red lockdown or being out running essential errands or meeting a client for work and having to pee, again, with nowhere to do so.

But she is also grieving all the celebratory rituals of pregnancy she won’t get to experience, especially after waiting — and wanting — for so long.

“And now to have it, and I feel like I’ve been ripped off,” Trevenen says. “It sounds stupid, but before getting pregnant, I was like, ‘…and then if it works, I’ll go for lunch with my girlfriends, and they’ll feel my belly’ and I’ll get to have a baby shower with my family — finally, for me. Not for everyone else.

“Like, the important thing is that you’re healthy and that the kid is healthy and that you finally got it and, like, this is great. And it’s a blessing,” she says. “But it’s a constant warring of emotions and feeling upset and then feeling upset about being upset.”

It’s worth noting, too, that people who have gone through successful fertility treatments may feel extra pressure to slap a big happy-face sticker on their experience.

“And research bears that out,” WHC’s Bockstael says. “People who have had fertility challenges, a history of pregnancy loss, people who adopt feel more shame and stigma around naming any feelings about the difficulties of parenting, just because they have additional pressure to feel grateful for every moment.”

● ● ●

Like Trevenen, Tess Klachefsky is mourning what could have been.

“I feel really angry and really resentful about being robbed of my mat leave,” she says. “With my mom dying, and now in this new phase of life and feeling so alone, I was really looking forward to having like, you know, Mommy and Me classes. Several of my friends also had babies, so getting together going for lunch — just really, really normal things.”

Family members and friends being unable to hold or even meet their babies has been a source of heartbreak for all the parents interviewed for this story. For Cyara Bird and Katie German, not being able to have their older kids meet their new sibling in the hospital was especially hard.

“My mom hasn’t held him yet,” German says, her voice cracking with emotion. Her December due date meant a code-red birth. Her extended family is missing the ‘baby-baby’ time, as German puts it, when they are squishy, wrinkly and new.

“My heart will remain broken forever because my Nana and Papa didn’t get to hold my son as a tiny newborn,” Bird says. “Time is so precious and if I could’ve changed one thing about this experience, it would’ve been being able to visit my grandparents after giving birth.”

“The saddest thing I think was not being able to introduce him to my family right away,” Andrea Tiwari says. “Everyone was just so excited after the loss of my dad to have something really joyous to look forward to.”

Trevenen, too, feels bad for her in-laws in Calgary who are missing the pregnancy of their only grandchild. “They feel like they’re getting ripped off, too. They don’t get the experience. My mom can at least come and stand on the front step and wave.”

It’s takes a village to raise a child, the saying goes. But what happens when you can’t gather as a village?

Klachefsky offers some practical advice for those who may have new parents in their circle. “Don’t say, ‘Let me know if you need anything,’” she says. “Replace that with an action. So, ‘Hey, I’m gonna bring you dinner tonight. It’ll be on your steps.’

“Check on the new moms in your life,” she says. “Any mom, but, especially the new moms. I think we’re kind of suffering. It’s been a really, really difficult time.”

During her pregnancy, German was able to find community virtually. “I got to take a prenatal class online with (midwife) Melissa Brown through Zaagi’idiwin (an Indigenous maternal health and wellness community) and getting to participate in it made me feel way more knowledgeable and gave me something to focus in on and be excited about rather than concerned all the time,” she says. “Being a Métis woman, it was good to have the traditional knowledge, since I couldn’t connect through regular ceremony. It was ceremony in itself.”

Tiwari is staying in close virtual contact with her mom and two younger sisters, who live in Ontario. “My son definitely knows what FaceTime is, because every time I hold the phone up now he’s waiting to see someone on the other end of the screen or someone talk to him.”

“People are missing that connection and all those gatherings and rituals that involve being part of your community that help mark this transition,” Bockstael says. “So things like baby showers or baptisms, blessingways, naming ceremonies — those all had to be reinvented, too.”

Several weeks ago, Rory and Lisa McDonald hosted a drive-by reveal.

“We told our family and friends by text, saying ‘Hey, if you drive by our house tonight, we’re going to have a light in our upstairs sunroom that’s either going to be blue or pink and you can find out what the sex is going to be,’” Lisa says.

“You’re upset that you can’t have a normal experience. And then you kind of get over it, and then you adapt. That’s what we’ve learned to do.”

And so, on a particularly freezing-cold night, friends and family distantly celebrated the happy news, a rose-coloured light in the December darkness. It’s a girl.

jen.zoratti@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @JenZoratti

Jen Zoratti is a Winnipeg Free Press columnist and author of the newsletter, NEXT, a weekly look towards a post-pandemic future.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.