Residential reckoning National historic site aims to tell school's story from Indigenous survivors' perspective inside

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 13/11/2020 (1849 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The first time Wanbdi Wakita ran away from residential school, he was doing so to help a young cousin.

His uncle had dropped the boy off at Birtle Indian Residential School and told Wakita, a boy of no more than 10 years old himself, to take care of him. Wakita promised he would. Wakita had been at the school for a few years by that point. He knew his way around. Looking after the little ones was important to him.

One particularly lonely night, Wakita discovered his cousin crying. “I don’t like it here,” the boy said. “I want to go home.” The next morning, when the residence was still silent and day had barely begun to break, the two boys slipped out the front door and took off running.

The Birtle school cuts a foreboding, imposing figure, perched high on a hill overlooking the western Manitoba town — like a prison, or a villain’s castle. It’s about as far away from home as one can get.

Once the school was out of view, they slowed. It had begun to rain.

When they reached Highway 83, they accepted a ride from a farmer who got them as far as Virden, roughly 70 kilometres south of Birtle. Home — Sioux Valley Dakota Nation — was still another 40 km away to the east, a short drive but a long walk for two boys now soaked through by rain.

And then, headlights. A big green station wagon pulled up behind them.

“I knew who it was,” recalls Wakita. “It was the administrator. He said, ‘Get in.’ He had two big boys there, ready to chase us if we ran away, I guess.”

The boys watched through the rain-splattered back window as home, and all of its comforts, got further and further away. In Wakita’s stomach, dread bloomed like an ink stain.

And that night, in front of the entire school, Wakita and his cousin were made examples of.

“He took our pants down and strapped us really hard,” the Dakota spiritual leader and Sundance Chief, now a big man of 77, remembers. “Oh boy, that was hard. He caused an injury to me which I still suffer today.”

For most of the 1950s, Wanbdi Wakita lived through the oppression, humiliation and abuse of the Canadian residential school system, first at Birtle, then at the Portage la Prairie Indian Residential School. He is one of more than 150,000 First Nations, Inuit and Métis children who were taken away from their homes and families, and denied their culture.

For nearly a century, these schools existed across the country, robbing generations of kids of their childhoods, their identities, their ways of life. Canada’s last residential school closed in 1996, but the trauma reverberates.

Many of the physical structures across the country are gone now, demolished. Few have been repurposed. In Manitoba, only three original residential school buildings remain: Birtle, Portage and part of the Assiniboia Indian Residential School in Winnipeg.

Assiniboia, located on Academy Road in River Heights, now houses the Canadian Centre for Child Protection. For a long time, Birtle sat vacant, the site of trespassers and partiers, until it was purchased off Kijiji in 2015 by a private buyer.

But Portage, as of September, is a national historic site. It’s one of just two residential school sites in the country to receive such a designation from Parks Canada. The other, located in Nova Scotia, has no structures. The Canadian government also formally recognized the residential school system “as an event of national historic significance.”

The preservation of a former residential school is a complicated, emotional issue. What do you do with a haunted house? Do you burn it to the ground or feel the catharsis of a wrecking ball? Or do you tell the stories of the people who suffered there, and keep it as evidence of a shameful, dark history? A tangible, undeniable reminder that yes, something terrible happened, and yes, it happened right here.

• • •

The former Portage la Prairie Indian Residential School sits on the Keeshkeemaquah Reserve on Long Plain First Nation, overlooking Crescent Lake. Elder, residential school survivor and former Long Plain chief Ernie Daniels acquired both the building and the lands in 1981 as part of an outstanding treaty land entitlement.

From 1984 until 2000, it was the home of Yellowquill College Inc., which relocated to Winnipeg. Since then, it has housed various office spaces, the Manitoba First Nations Police, and a tiny museum — the glimmer of a bigger dream the designation will help realize: a full residential school museum, in the heart of Canada.

Long Plain First Nation chief Dennis Meeches says the national historic site designation was a long time coming. He acknowledges that “there’s a lot of mixed feelings about preserving that type of history. But it’s really, really important that we don’t lose sight of that history.”

There’s a lot of work to be done but the goal, he says, is to transform it “from a place of hurting to a place of healing.”

In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission put forth 94 calls to action. No. 79 reads, in part: “Developing and implementing a national heritage plan and strategy for commemorating residential school sites, the history and legacy of residential schools, and the contributions of Aboriginal peoples to Canada’s history.” The designation is a response to that call.

Stephanie Scott is the interim director of National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, based at the University of Manitoba.

Scott, too, notes that when community wants to turn a building or space into a place where others can come, witness and learn, not everybody from that community will want to participate in that process.

“You are going to get a very diverse opinion about how and what is the best way to commemorate, and some survivors will absolutely want nothing to do with it,” she says. “But there are also others that want to say we need to acknowledge this building or site and let others know that this is what happened and this is the true history of Canada.”

Whatever the designation or commemoration — whether it looks like a healing garden, mural or a museum — Scott says it’s vital that the project be community led. The NCTR is also setting up a program to guide communities and survivors through the national historic site designation process that Long Plain went through, including the Parks Canada application, so that other sites and spaces may follow.

In 2005, the Portage school was designated a provincial historic site. The plaque outside doesn’t convey the horror that happened here. There are no references to humiliation, hunger or abuse, just that the building was “composed with a restrained classical vocabulary.”

A museum is a chance to correct that narrative. “We need to tell the story through Indigenous eyes, through our survivors,” Meeches says.

Inside, Lorraine Daniels, the executive director of the museum and a residential school survivor herself, has begun the herculean task of researching, sorting and gathering artifacts. Some are heartbreaking. A rusty military-style bed with peeling pink paint. A mannequin sporting the severe bowl haircut given to the girls. And three leather straps, of varying lengths.

The length depended on the age of the child being beaten.

• • •

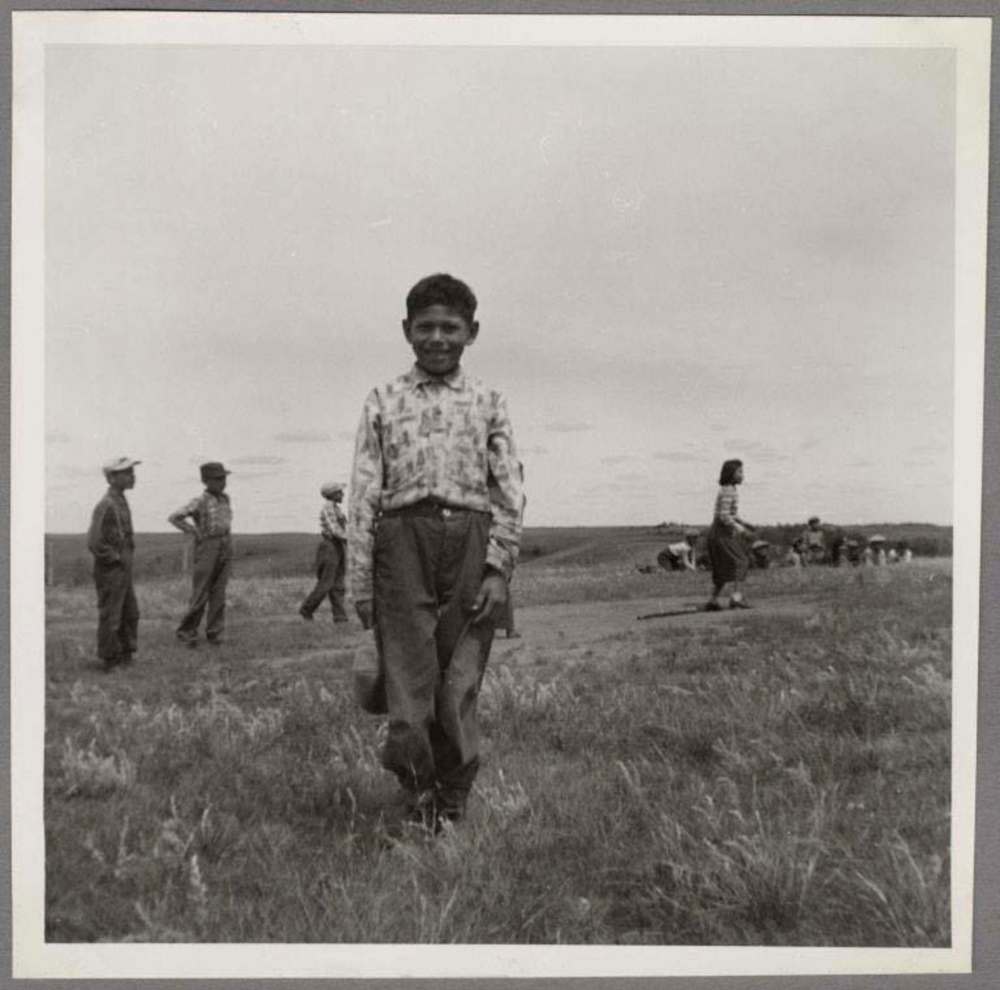

Before residential school eclipsed his life, a young Wanbdi enjoyed his childhood on Sioux Valley Dakota Nation.

“When I was at home, my parents and my siblings and my grandpa and my relatives, we done really good,” he says. “We were happy. We were safe. I grew up on a small farm. Just enough to get along. We learned all of the, what I call, the Dakota ways. Greeting one another with not our names but by relative. ‘Hello, my younger brother.’ ‘Hello, my sister.’ But in our own language. I grew up with my language.

“The food too. My kunsi — my grandma — and my mum, they had good food always. My dad and my grandpa were good hunters. They supplemented our meals that way. Us kids would go pick berries and stuff like that. We ate off the land, which is much better as people found out way later.”

He grins. “All the stuff that’s coming out now, like, the ‘bone broth?’ That’s nothing new. ‘Land-based education?’ That’s nothing new. We had that for thousands of years.”

Wanbdi was born in 1943, and falls right in the middle of seven children. Three brothers, three sisters, all born at home with a midwife.

When he was bigger, he relished doing jobs around the farm. Everyone had to pitch in.

“Just like my brother said, ‘I was seven years old before I found out my name was not ‘Get Wood,’” he says. That grin again. “‘Hey, Get Wood.’ We all had jobs. And it was fun. It wasn’t a chore or a hardship. Humour was always a big part. Stories were a big part. It helped build the foundation for family.”

Wanbdi milked the cows and took care of the horses. “It built us up, knowing we had things we needed to do.”

Before he went to residential school, Wanbdi attended a day school on the reserve. Day schools were precursors to residential schools; they, too, were run by the federal government and Christian churches — and they, too, were the sites of assimilation and abuse — but children could stay in their communities.

Adventurous and eager for new experiences — a trait true all his life — Wanbdi was excited when he first arrived at day school. Kids he recognized from his community were outside, playing football. He ran to join the game. “Pass it to me!” he called out, in his Dakota language.

The boys stopped playing and stared at him.

“One of the older guys said, ‘You can’t speak Dakota, you gotta speak English,’” Wakita recalls. “That was my first day. Two or three minutes later and I was told by my own people that I can’t speak Dakota. That’s a pretty harsh thing.”

Day school was a preview of his life at residential school at Birtle, which was originally run by the Presbyterian church. “I was silent for four or five months before I said a few words in English,” he says. “We were forbidden from speaking Dakota. We were hit — strapped — with a ruler. That’s what she used if we spoke our own language.

“I didn’t like school,” he says. “Oh boy. We had a very mean teacher. I’d never seen her smile once. She was always mad for some reason. She twisted my ear. I could hear my ear cracking. And she used to throw chalk and those brushes at us if she thought we weren’t doing good. That’s what she used to do.”

He pauses. “One thing, though: she made us good ball players because we used to catch that stuff after a while,” he says with a laugh.

Wanbdi was tasked with hauling the giant bags of laundry downstairs, twice a week. On the way back, he passed a pantry area. “Bread, not sliced. And there’s pails of jam and peanut butter. So I would put them in the bags and take them upstairs.”

After lights out, the kids would feast. They were almost always hungry, especially the little ones who would often have their food stolen by older, bigger kids.

“Twice a week we would have a party,” Wakita says. “I learned how to steal at a young age.”

Stealing wasn’t just a matter of survival.

“We wanted to live,” Wakita says. “All the hurts the kids went through — it’s not enough to address the pain, the hurts we went through, just by doing those kinds of things. You try to, but it didn’t. Lots of us came out of residential school drinking alcohol, doing drugs. And lots of them died early.”

Wakita doesn’t know why he was transferred from Birtle to Portage la Prairie; children, he says, were often not told where they were going or why. He recalls a summer he had to stay at Portage because his mother was quarantined with tuberculosis.

“I stayed there and washed them, the second-floor windows, all the way around that big school.”

• • •

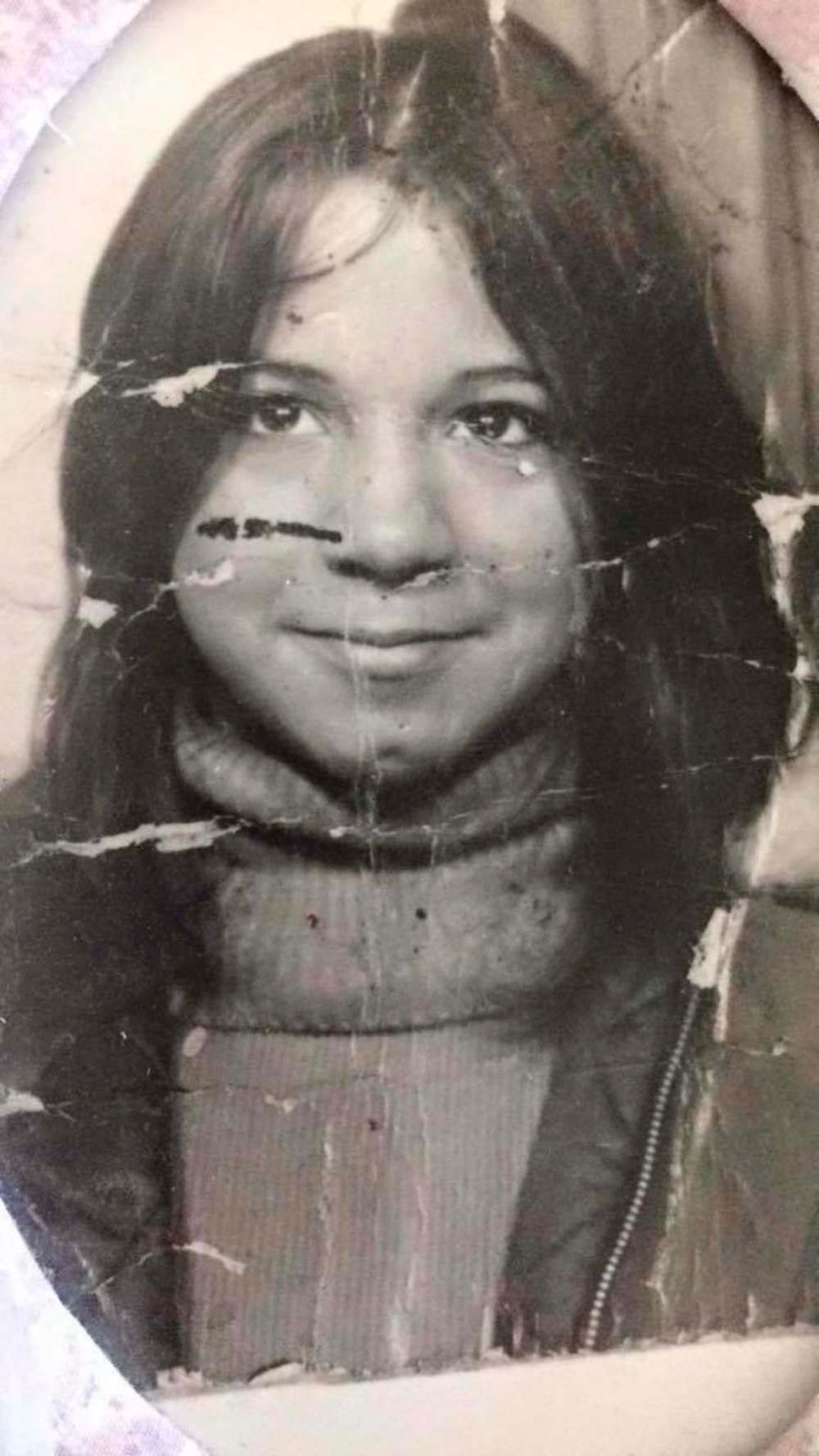

Jennifer Wood didn’t know she was going to be left behind.

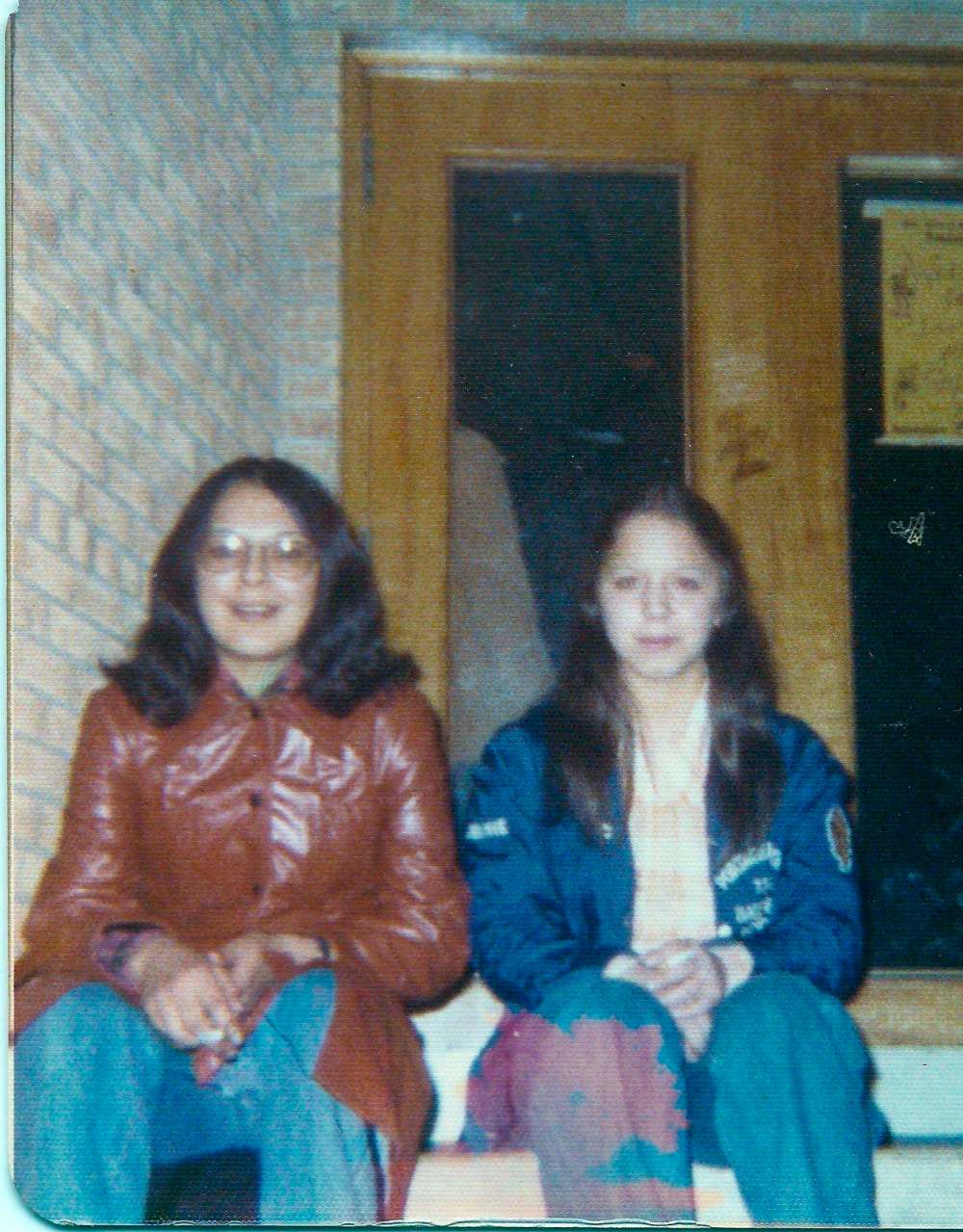

She was 13 when her father brought her to the Portage la Prairie Indian Residential School from Oxford House in 1973. The standard of education wasn’t good in northern Manitoba, she recalls, so her father thought it best she attend Portage. She was a student there until it closed, in 1975, then boarded in Portage la Prairie for two more years after that.

“I was quite shocked when he introduced me to the head staff at the school, and then he said, ‘Well, I guess I’ll be going now,’” recalls Wood, now 61. “And I said, ‘Where are you going?’ He goes, ‘Well, I’m going back to Oxford House.’ I was really taken aback. That’s how I met my first friend there, who was kind of listening. Not intentionally, but was standing by the doorway. We made friends then. I had to soon and quickly compose myself and settle into the idea that this is where I’m going to be living.”

Wood, who is Ojibway, is originally from Neyaashiinigmiing First Nation in southern Ontario. Her family moved to northern Manitoba in 1970. Many of the other girls at school also came from northern Manitoba. Wood made a lot of friends at residential school, lifelong friendships that still sustain her to this day.

Wood struggled academically — “I remember wanting to become invisible and not be seen so no one would ask me a question,” she recalls with a laugh — but thrived in extracurricular activities.

“I made a lot of friends and got involved quickly in a lot of things, to busy myself,” she says. “What else are you going to do, right? You either gotta set your mind to making it or you’re gonna be a broken person.”

As a student of the 1970s, her experience of the Portage school is different from someone who attended in previous decades. But then, the pain residential school inflicts isn’t always physical.

“They endured a lot more suffering than I certainly did, but the loneliness, the separation from your family, it’s the same, right? You endure that. You endure the breakage from your family, and your loved ones, and the comfort, and missing out on your traditions and the values that you could have learned.”

One Christmas, Wood’s good friend Madeline Gamblin (now Gamblin-Walker) invited her home to Norway House for the holidays.

“I really, really felt so good about that,” Wood recalls. “They made traditional foods: beaver and moose and bannock. I felt so welcomed within their home. That’s how they all were. They were all kind and loving. They all spoke their language, which was Cree at the time, and that’s what I learned there. I’ll never forget that.”

The warmth and kindness of her friends not only helped her survive, but kept her connected to her culture.

“We all supported each other and they introduced me to a lot of things that I would have never known or got to know if I hadn’t met them.”

Now, Wood is a mother of two daughters, and grandmother to 11 grandchildren — “my own baseball team,” she says, affectionately. She’s worked in both event planning and politics; for 10 years, she worked alongside the late Elijah Harper as a political assistant, and was former grand chief Sheila North’s campaign manager for her run for national chief of the Assembly of First Nations. She’s worked with residential school survivors and is a passionate advocate for missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls.

Wood’s mother was a residential school survivor, as were five of her siblings. Her mother didn’t talk about it much because, Wood suspects, she wanted to shield her children from the pain of her experience.

But the pain of residential school is one that is inherited, one that ripples through generations.

“And that’s why a lot of our people are, you know, you see on the streets — they didn’t just all of a sudden decide they’re going to become homeless or poverty stricken,” Wood says. “This is all about intergenerational trauma. They’re experiencing the pain of their ancestors and their own families.

“Even though you may not have gone to the school, you’re certainly affected that your mother went,” she says. “It’s in your blood memory, in your DNA.”

• • •

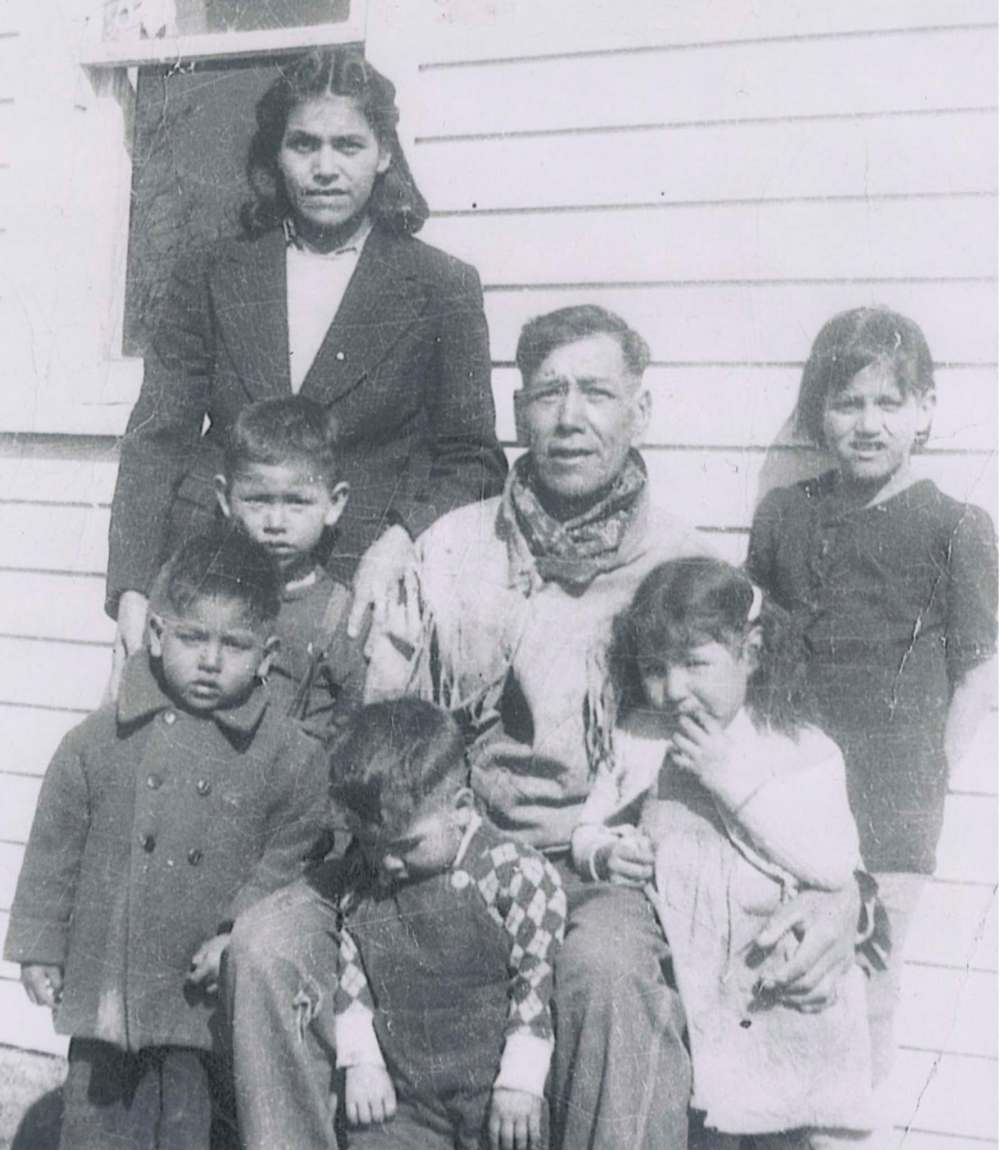

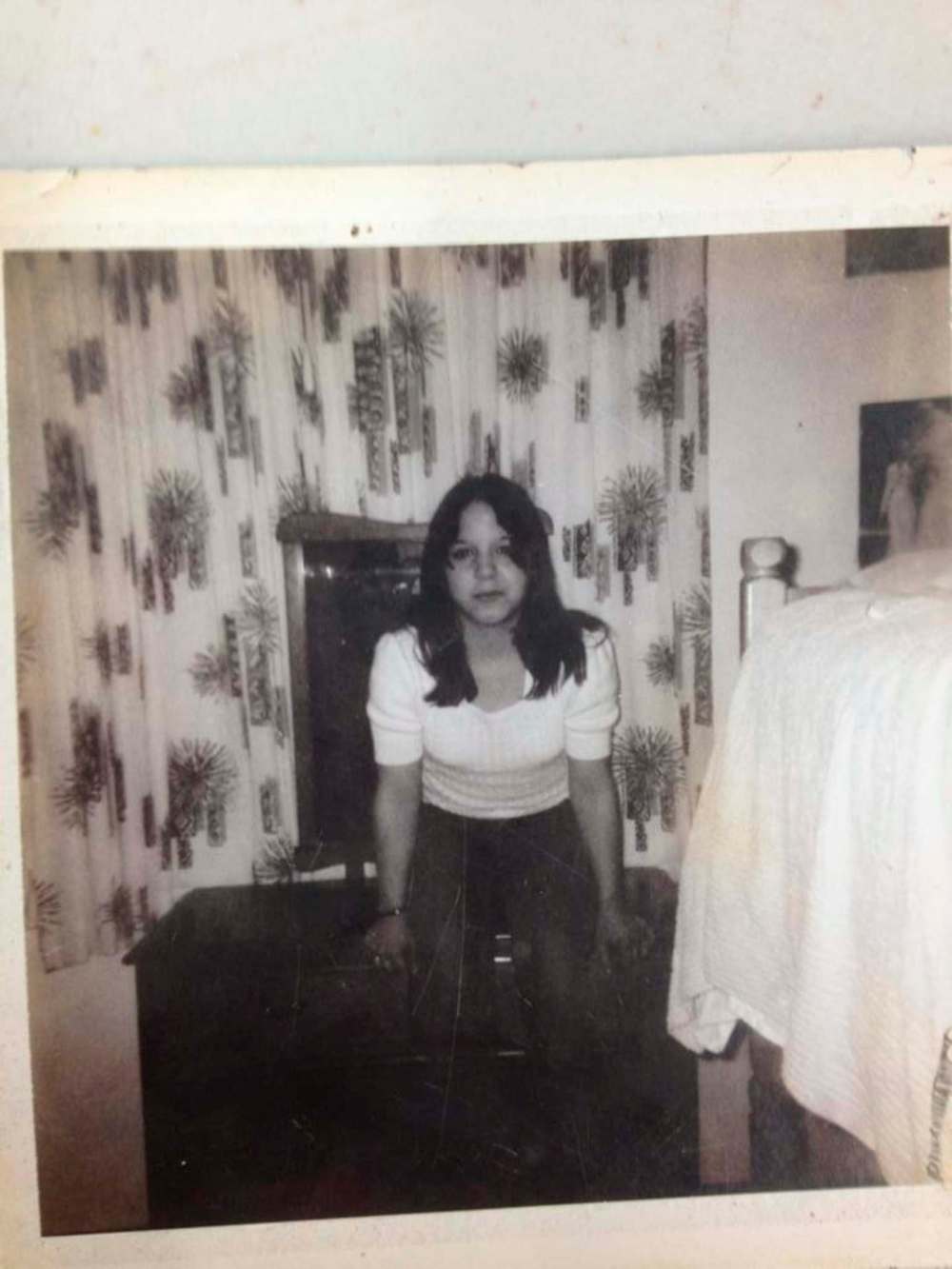

Pixie McLean-Moar, now 53, was in her thirties before she ever knew her mother, Anne McLean, attended the Portage la Prairie residential school. (Her real name is Laura, but nearly everyone calls her Pixie.)

Anne, now 78, was only four years old when she was sent to residential school, and was there until she was 12. Her entire childhood was taken away, marked by physical abuse and the erasure of her culture. Talking about it remains difficult for Anne.

“We never knew about it,” says McLean-Moar, who was born, raised and lives in Brandon. “It was never ever talked about, just kind of here and there. My aunties would be talking about it and, you know, my mom would be crying. And we’d be wondering, like, ‘I wonder like, why she was so upset.’”

Anne’s suffering didn’t end with residential school. She lost her status when she married Pixie’s father; under the Indian Act, an Indigenous woman who married a non-Indigenous man would lose her status. She lost three of her children to the ‘60s Scoop. Anne grew up speaking Ojibway; her children did not.

It wasn’t until 2008, when former prime minister Stephen Harper made a statement of apology to residential school survivors, that Anne began really sharing her past with Pixie.

“It opened up my relationship to her,” McLean-Moar says. “Like, ‘Wow. OK. Now I know why my mom is the way she is.’ It made me take a step back and just be sympathetic. Like saying, ‘OK, this isn’t all on you because there’s there’s a lot of history there.’ Like, her and her mom didn’t have a good relationship. So naturally, that kind of spilled out within our family. And so we were able to talk, and we were able to share stuff.”

McLean-Moar has experienced first-hand the intergenerational trauma of residential school.

“I can honestly say I think it was within the last 20 years — maybe 10 or 15 — that she would actually say ‘I love you,’” she says of her mother. “It’s so hard for me to say back because it wasn’t said. Or a hug.”

The healing process is slow and ongoing, and McLean-Moar is still learning about her mother and, in turn, about herself. A puzzle constructed from 20 years of pieces.

Her mom was able to buy her own place with her settlement money.

“But it’s still hard,” McLean-Moar says. “Like, it doesn’t take away the memories, money.”

• • •

The second time Wanbdi Wakita ran away from residential school, it was for good.

All these years later, Wakita remembers the date he walked out the front doors of Portage la Prairie Indian Residential School: it was Feb. 5. He was a teenager and, this time, he got on a bus. He was home before anyone knew he was gone, but it wasn’t the homecoming he’d envisioned.

“My dad was kind of a rough guy,” Wakita says. “He went into the Second World War and came home psychologically damaged. He was rough on me. He told me that if I didn’t go to school I couldn’t stay there.”

So, Wakita started walking. He thinks now that he should have gone to an auntie’s. “I was mad,” he says. It was late afternoon, dusk already. All he had was pair of socks, a pair of pants, a shirt and his anger.

And then, headlights. This time, however, they didn’t belong to an unsmiling school administrator.

“It was this little old farmer. He had little round glasses on and an old cowboy hat. He said, ‘Where are you going?’ I said, ‘I don’t know but I’m looking for a job.’ And those farmers, you know, they kind of talk funny. ‘By golly,’ he said, ‘I was looking for somebody for March but you can start tonight.’ Just like that.”

Wakita worked on the farm for a few years, and then another, before a new path opened before him. He saw an advertisement in a newspaper. “‘Join now,’ it said,” Wakita remembers.

A few weeks later, the mail came. A letter and a train ticket. “So, I’m in the army.”

For six years, Wakita served as a private in Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, including peacekeeping missions in Germany.

“I didn’t know it then, but residential school and joining the army — they were matching,” he says, lining up his hands. “They were connected. I was already angry at the residential school, and I learned how to kill people in the army. But I didn’t know these things until much later and I started to do some healing. In the meantime, all I’d done was drinking and fighting.”

In time, Wakita’s own experience in the army would help him better understand his father. After his father died, Wakita says his father came to him in spirit form, to ask for forgiveness. And Wakita was able to give it.

Today, Wakita offers guidance and ceremony in his work as a Wicasa Wakan, or holy man. For three decades, he provided counselling support to incarcerated men; for the past two years, he’s been the unkan or grandfather-in-residence at the University of Manitoba’s Access Program. (In Dakota tradition, the term Elder is not used.) Wakita has been honoured many times over for his work including, in 2016, the Order of Manitoba. He works alongside his wife, Pahan Pte San Win, who share knowledge as BearPawTipi — a nod to Wakita’s grandfather, Wa Sicuna (Bear Paw). They have a tipi and purification lodge in their backyard in St. Andrews. Wakita still likes to pick medicine, though it’s harder for him, now.

“My wife helps me out a lot. She knows more than me — me, I’m just a grumpy old guy,” Wakita says with a laugh. “We have it good. We have a nice house here, we have a nice yard. We eat good food. It’s just the two of us now.” His 12 children have flown the nest.

Wakita still gets angry sometimes, but he has better ways to cope. In order to get where he is today, however, he had to deal with his anger and trauma head on. He could no longer avoid it.

“I still had to take this chunk out that I carried and fill it with my culture and then go and practise it in order to heal,” he says. “I tried to look out there. I soon realized that I was looking out there only to try and have fun. ‘Ah, forget about it, I don’t want to talk about residential school. I want to go out and have fun.’ Never dealing with what I needed to do for healing, until I figured out my inside stuff. That’s pretty hard to do sometimes. Even getting back your feelings is a hard job.”

Helping younger generations heal — to feel feelings again — is a big part of Wakita’s work. There’s an exercise he does with young kids and youth. “I give them five seconds to tell me what they’re feeling right now. And a lot of them, no feelings. A lot of them.

“And of course, the reason why I’m doing that, is because I hear them say, ‘Well, I don’t care,’” he says. “You have to care. It’s your heart. That’s how much damage has been done to these young people.”

• • •

“I know the wish of the people,” Wakita says of the Portage school’s new designation.

“You know, if it’s going to help the community, that’s why they’ve done that,” he says. “Most of us will not have anything to do with that school.”

McLean-Moar would like to see the Portage school restored in such a way that people can actually see what a classroom looked like, or a bedroom. Her mother, meanwhile, shares Wakita’s view.

“She said she would sooner see it torn down, but she understands,” McLean-Moar says. “When I talked to her, I said, ‘You know, people need to be educated.’ You can’t understand what people are going through if you don’t know their history. And she was in agreement with that, too. When we drive by, it brings back memories. But she knows people got to know the story behind it.”

Wood was happy about the designation. A building, she says, is there. It exists. It doesn’t allow you to forget.

“It’ll educate the greater, larger public — they’ll know about it now,” she says. “Because it’s all about everyone coming together and healing together, right? Walking that road together. I want the greater, larger Canadian public to learn, and to know that this school existed, I want them to know the experiences that the children have endured. I want them to walk away and to be one of those people that will help to educate everyone across the board, so that we have a common understanding of one another, and that there’s a balance and we can stand side-by-side and coexist.

“I don’t believe in tearing it down,” Wood says. “I believe that would do nothing. I believe that leaving it there and honouring it as one of the historic sites in Canada, to me, is a real recognition of the truth.”

jen.zoratti@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @JenZoratti

Jen Zoratti is a Winnipeg Free Press columnist and author of the newsletter, NEXT, a weekly look towards a post-pandemic future.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Tuesday, November 17, 2020 6:36 AM CST: Removes duplicated words