Health system with ‘unavoidable’ long-term care deaths is a failure

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 22/10/2020 (1876 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

In the fight against the novel coronavirus, we have seen two types of tragedies.

There have been the unavoidable kind that come with the spread of a virulent new disease: the loss of life and quality of life; the crippling of social and economic activities; the suffocating stress on our health-care system and the people who keep it running.

And there are avoidable tragedies. These are the things that we could largely have prevented if we were more generous, more organized and more observant. In that category, we must place the massacre of our oldest and most vulnerable citizens.

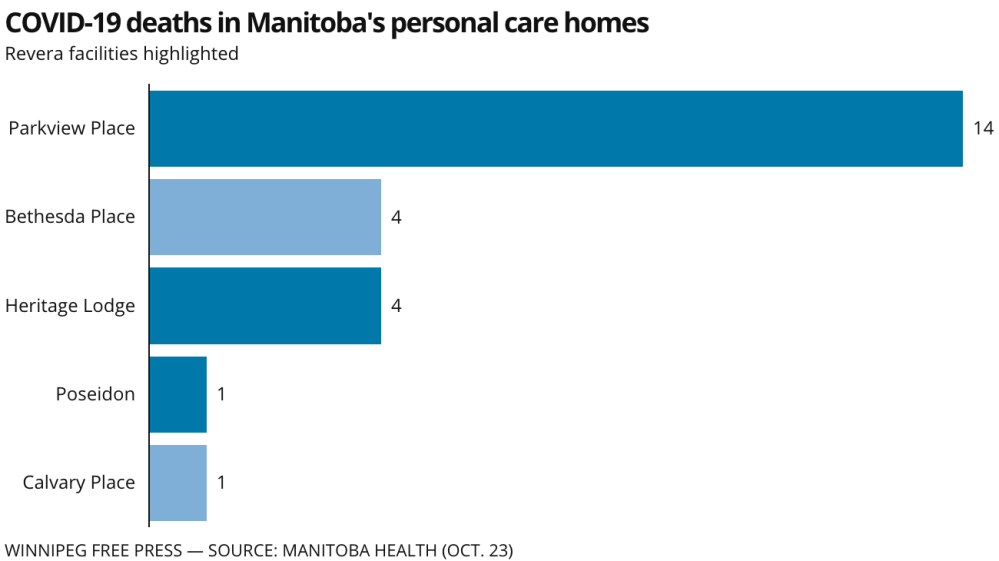

In Winnipeg, public health officials are struggling to contain a growing COVID-19 outbreak at Parkview Place Long Term Care Home, where there have been more than 100 confirmed cases (including 24 staff) and 14 deaths. It is the worst outbreak at a personal or long-term care facility in Manitoba.

Why the virus is ravaging Parkview Place is the source of great debate. There have been some pretty robust public health protocols in place for months now to protect the residents of long-term care facilities. But the novel coronavirus is a tricky adversary; it only takes one person to acquire the virus and then visit or go to work in a personal-care home for an outbreak to occur.

The ease with which the virus circulates, along with the frailty of long-term care residents, has manifested in a theory that these deaths are largely unavoidable. That’s certainly the working theory embraced by Manitoba Health Minister Cameron Friesen.

A week ago in a CBC national radio interview, Friesen said that the high number of deaths in facilities such as Parkview Place was tragic, regrettable but largely “unavoidable.”

In offering that opinion, Friesen was attempting to divert attention away from the role his government may have played — deliberately or inadvertently — in creating the conditions that were ripe for significant loss of life. And make no mistake about it, the disproportionate number of deaths in Canadian long-term care facilities are the direct result of government action.

Over the summer, the Canadian Institute for Health Information did a comparison of COVID-19 deaths among long-term care residents in 16 Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development countries. The findings were alarming. Although Canada’s overall COVID-19 death rate is among the lowest, we’ve had the highest overall percentage of deaths involving residents of long-term care facilities.

More than 80 per cent of all COVID-19 deaths in Canada occurred in long-term care, nearly double the average of other OECD countries. Our woeful performance on this metric has little to do, it seems with public health responses to the pandemic; even among those countries that instituted nearly identical social and economic restrictions there were far fewer COVID-19 deaths among seniors in institutional care.

How could a country with a universal health-care system that is considered among the best in the world fail this one constituency? Contrary to what we might like to believe, taking care of older Canadians is just not a national priority.

Overall, Canada has an admirable record of spending on health care. According to another CIHI analysis of health expenditures in OECD countries, Canada spends 10.7 per cent of its GDP on health care, which is significantly above the OECD average of 8.8 per cent.

However, when it comes to the share we spend on care for our oldest and most vulnerable citizens, the equation flips. According to the OECD, Canada devotes only 1.3 per cent of its GDP to long-term care, which is below the OECD average of 1.7 per cent and nearly three times less than the top-spending countries.

In elder care, you clearly get what you pay for. And in this case, what we have is a system that is so starved of precious resources that could be used to help protect long-term care residents when a public-health crisis hits. For example, in its analysis, CIHI found that Canada is well below the OECD average for the number of nurses and support workers per 100 long-term care residents.

What this all speaks to is a need to rethink care for the elderly and others who require assisted living. We’re just not living up to our imagined values in this critical area of the health system. And claims by political leaders that the deaths are unavoidable are not going to make the situation better.

Friesen should take some comfort in the fact that this is not a problem that his government created. You can go back and point an accusing finger at every government and health minister that has ever overseen our system of long-term care.

COVID-19 has exposed a chronic mismanagement of elder care that goes back decades. From a public policy point of view, it is the can that keeps getting kicked down the street with each new government. The deaths accumulating at Parkview Place is just the latest evidence of our long-standing and collective failure.

That acknowledgement does not absolve Friesen from providing a solution. That may be a tough fix to find when he works within a government that has attempted to engineer the most affordable health-care system in the country.

But at the very least, he could start by acknowledging that the deaths at Parkview Place were avoidable.

dan.lett@freepress.mb.ca

Born and raised in and around Toronto, Dan Lett came to Winnipeg in 1986, less than a year out of journalism school with a lifelong dream to be a newspaper reporter.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.