Lost treasure

Discovering a lovingly preserved Titanic model we worked on together an unexpected gift of unsinkable memories before first Father's Day without my dad

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$19 $0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for four weeks then billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Offer only available to new and qualified returning subscribers. Cancel any time.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 17/06/2020 (1652 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

When I was a little girl, I became briefly obsessed with nautical disasters. It was an early sign of what would become a lifelong fixation with how people behave in moments of crisis: the men who gave up their spot on the lifeboat. The men who forced their way on. The captain who watched his ship die, and stood firm.

In the midst of this obsession, my father, cheerfully unruffled by the macabre tenor of his youngest daughter’s new interest, brought home a model Titanic, one of those paint-your-own kits they sell at hobby stores. We spent hours working on it at the dining room table, dabbing brushes in tiny pots of paint while I rattled off Titanic facts.

“Dad, did you know the ship broke in two pieces when it sank?”

With a few careful brush strokes, a miniature plastic propeller is clad in silver.

“Did you know the band kept playing the whole time? The survivors heard the music.”

We tap rows of gold dots along the hull, to suggest light beaming out from inner cabins.

It wasn’t an elegant paint job, or a historically accurate one. The brown to suggest wooden decks smeared over the ship’s white upper walls; its four iconic funnels were covered with the same brown, though in real life, they’d been a distinctive shade of orange-tinted yellow.

But it was our Titanic, that we’d started and finished together, and for many years it sat on a bookshelf like a work of fine art. Eventually, it was packed away, and I never wondered too much about where it had gone. But it remained on display in both of our memories, and every so often, we’d dredge it back up.

“Remember that model Titanic we made?” one of us would say.

Then we’d smile for a long moment, eyes losing focus as our gazes turned inward, lost in a wordless reverie of those hours spent hunched over paints at the dining room table. The best memories aren’t so much a snapshot of the past, as a vessel to hold present meaning; less about the messy details, more about who shares them.

Well, I’m the only one who remembers painting that plastic boat now.

The best memories aren’t so much a snapshot of the past, as a vessel to hold present meaning; less about the messy details, more about who shares them.

It would be easy to write that negotiating the first Father’s Day without my dad is complex. The real problem is the opposite: it’s entirely too simple. There’s no card to buy, no visit to make, no morning phone call to deliver. It was a day that held meaning, and now it has little, and that absence of complication is what aches the most.

Yet I am surrounded by traces of him, recovered from the depths of his closets. My dad saved everything, from the hand turkeys I drew in preschool to the programs of school concerts. I used to tease him for this, without admitting that I’d inherited the same sentimental streak. Now, I understand the impulse much better.

In the months since my father died, I’ve become an archeologist of our life, picking fragments from boxes and trying to piece them into a historical record of a love story told in a thousand tiny adventures. The glass jar filled with hotel matchbooks, souvenirs from old road trips; a pamphlet from the Inn of the Woods in Kenora.

Two weeks before Father’s Day, I picked up yet another box of stuff, this one long tucked away in his garage. In his distinct slanted handwriting, he’d labelled it with a Sharpie marker: DAVID’S MEMENTOES. Underneath, and perhaps written later, he’d added a second description: TITANIC MODEL.

The fact he’d written it on the box hits me with the force of the ocean, almost knocking me over.

Inside, I searched for the boat, frowned when I didn’t see it. Then I noticed it: a long oblong shape, wrapped in old obituary pages of the Free Press, for its protection. He’d wound the whole thing with duct tape, and on that strip of silver tape, he’d written another short label.

Titanic Model. Made by Melissa and Dad.

I gaze at this for a minute, thinking about the meaning in what he had written. Not “David,” his name, but “Dad,” his relational appellation. A message to me, no doubt, knowing the day would come when I would bring the model back into the light on my own; but also a statement of identity, of how he named himself.

This is the part that, not having children, I know I can’t fully understand. What is it that transforms a father into a Dad? How does a connection forged of genes or just circumstance become a bond so strong, it can define how a man sees himself in the world, can even stretch unbroken long after death?

I look at the cardboard boxes again. I remember how I’d tease him for saving everything. I remember how he’d just laugh, knowing I didn’t yet understand. All those things, he was saving them for me. An inheritance of memories so that someday, a lonely daughter could once again remember what it was like to share them.

A whole life, packed into boxes. Not neatly, but done with love, hoping that would be enough.

So it always goes, with parents and children. Sometimes beautiful, sometimes messy, often imperfect and uncertain. And so it always goes that Father’s Day can be complicated, even where it is simple. For many, there is love and joy in the day. For others, there is pain in it — for what is lost, what is missing or just what never was.

This is the truth of it, then: a father can be made, but to be a Dad has to be earned. One hour at a time, or one road trip or one model made over a dining room table. A title that has to be chosen, before it will be given; for those who bear it, there are few more beautiful names in the world.

This is the truth of it, then: a father can be made, but to be a Dad has to be earned.

The newspaper-wrapped package sits heavier in my hands than the weight of its contents. It’s hard just to unwrap it, partly for fear of breaking something unseen, but also for the sense that in the unwrapping, I am undoing the work of his hands. But he left this moment to me as a gift, not a burden.

I take a pair of scissors, and carefully snip through the duct tape. Not the part with the writing.

After all these years, the model Titanic is largely undamaged. The four funnels still stand, although the jutting arms that hold the lifeboats have mostly snapped away. I don’t know what to do with it now. It can’t go back up on a shelf — too hard to look at. I can’t cram it back in storage — too precious to stow away.

That night, I close my eyes and imagine taking the tiny plastic ship west, through the mountains, to the edge of the sea. I imagine kneeling on a beach somewhere on Vancouver Island, which he loved, and releasing the ship to the water. In my mind, the waves crash over the bow, and the deck tilts and heaves.

Somewhere, on the wind, floats a whisper of song. I can’t hear him sing anymore, but the band still plays on.

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

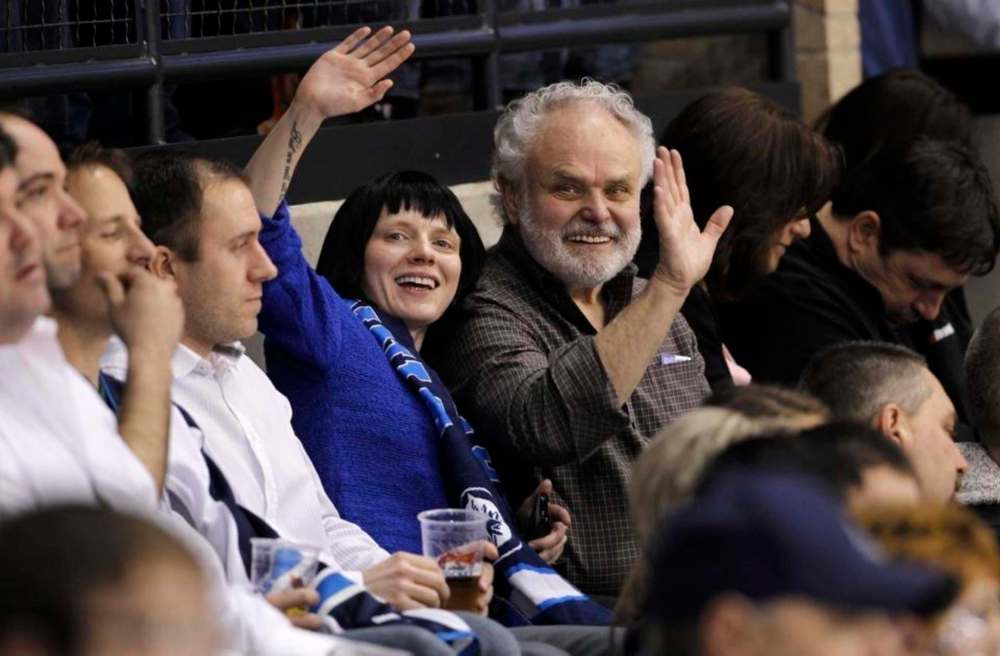

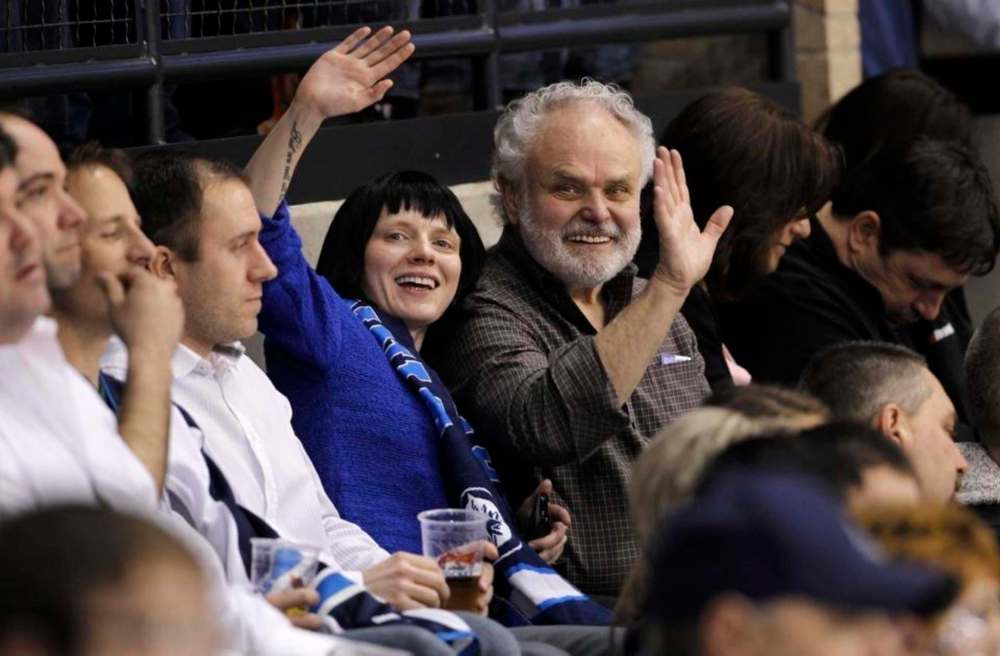

Melissa Martin

Reporter-at-large

Melissa Martin reports and opines for the Winnipeg Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.