Teachers union supports guidelines, training to clear up restraint, seclusion ‘grey area’

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 12/06/2020 (2009 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The Manitoba Teachers’ Society says it would welcome clearer guidelines on the use of physical restraint and seclusion in schools — practices a recent exploratory study suggests are used on students with disabilities to address behaviour challenges, and often not recorded in writing after the fact.

Manitoba doesn’t have any standards for the use of such intervention methods in schools or reporting requirements. Divisions act independently in offering their staff training to de-escalate situations to protect both themselves and their students.

Report details use of restraint against students with disabilities

Posted:

Some parents say their children were physically restrained to a chair at school, with arm splints and posey cuffs. Others reported their child had been confined to a cinder block-lined closet. In one case, a student came home often with torn clothing, after he had been “yanked around like a rag doll and forced into the quiet room.”

A new report authored by a Winnipeg researcher who specializes in inclusive education calls for that to change. Behind Closed Doors includes insights from 62 anonymous parents and guardians who took an online survey (July-October 2019) about experiences their children had during the school day at least once in the last three years.

The findings indicate a lack of consent for the use of restraint and seclusion in Manitoba, individuals’ frequent experience with measures and unreliable, untimely notification from school administration after an incident.

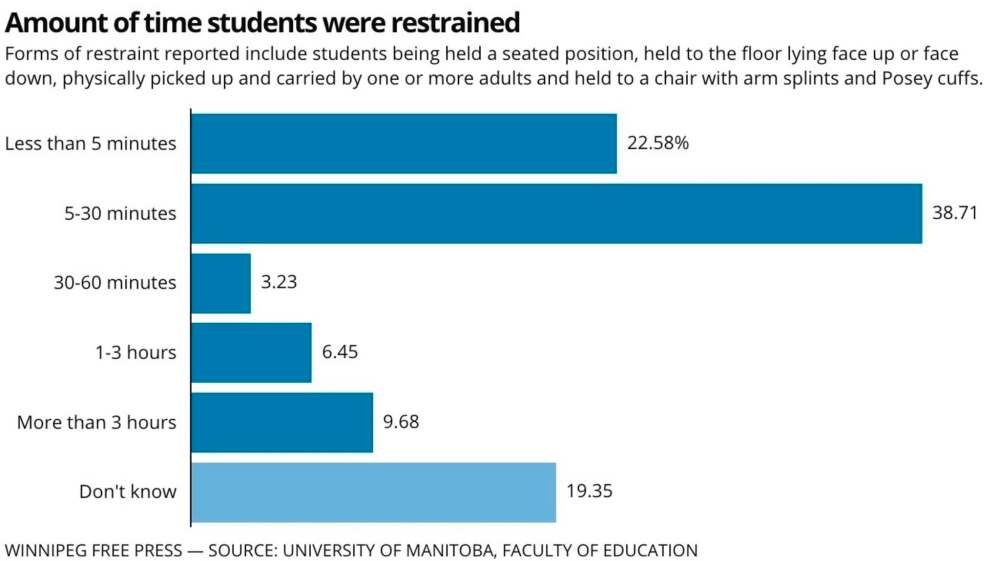

The restraint incidents included: being held both face up and face down on the floor; being held while forced to walk; seated with arms held by splints and wrists in fabric cuffs; and being picked up and carried.

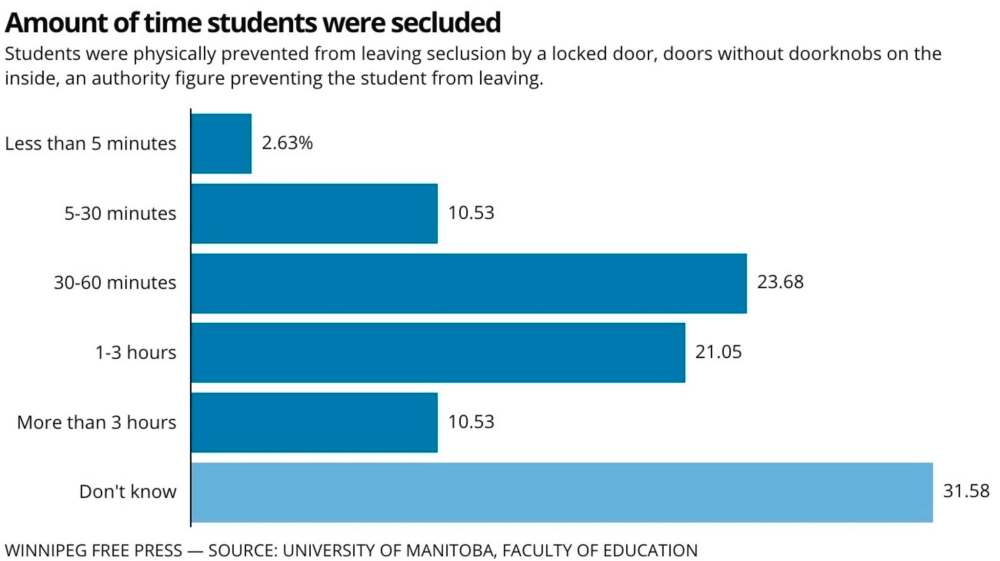

Parents also reported seclusion where their child was put in a four foot by four foot cinder-block closet or a room with a modified doorknob or without a handle on the inside.

Respondents, most of whom said they learned about the incident from their child, reported the involvement of special-education and resource teachers, school administrators, classroom teachers, teaching assistants and school counsellors.

“There’s no question — we would definitely be in support of guidelines for seclusion and support training…. There definitely is a grey area, and it’s a very difficult area,” said MTS president James Bedford, who represents upwards of 15,000 teachers in Manitoba schools.

Bedford said restraint and seclusion are last resorts if educators’ toolkits for de-escalation prove unsuccessful, adding that if a student identifies as having behavioural needs, teachers sit down with a principal to see if divisional support can be brought in. They will then develop a plan to address a student’s needs, he said.

MTS raised concerns about the need for improved access to clinicians and student support services during the provincial government’s K-12 education review. In the union’s submission, it called on the province to reduce wait times for learning-disabilities assessments so students who qualify for a special-education designation get support before learning difficulties lead to behavioural and emotional problems.

In Behind Closed Doors, author Nadine Bartlett, an assistant professor at the University of Manitoba, outlines six recommendations to address restraint and seclusion in local schools. Among them, provincewide standards and consistent reporting for accountability, the prescription of a standardized training program and the strict use of practices only during crises that could result in self-harm or harm to someone else.

Education Minister Kelvin Goertzen declined multiple interview requests about the report. Late Friday, a spokesperson said in a statement Goertzen had directed his department to “immediately” consult divisions and stakeholders about the findings and bring back recommendations to government on the use of seclusion in schools.

Bartlett suggests Manitoba look to Alberta, a leader in developing policy in this area in Canada. Pushback about the practices in that province prompted Alberta Education to develop standards for the use of physical restraint, seclusion and time-outs in schools late last year.

The guidelines promote prevention and de-escalation approaches to address outbursts. Restraint and seclusion can be used only in situations in which a student is exhibiting “dangerous behaviour” that is likely to cause self-harm or harm to others; neither practice is allowed to address “disruptive behaviour.” If an incident occurs, schools have to record it. The province collects the data from divisions on a monthly basis.

“The fact that there are no standards is really, when you think about it, quite shocking — that there are no enforceable standards for locking children up. There is no other place that that is true,” said Trish Bowman, CEO of Inclusion Alberta, an advocacy organization for the disabled. Bowman used both hospitals and jails as examples of institutions where there are strict protocols on seclusion.

Bowman said guidelines and reporting requirements in Alberta have resulted in more public awareness and some schools dismantling seclusion rooms.

In 2018, Inclusion Alberta undertook a study about student experiences with restraint and seclusion; Manitoba’s study was modelled after it. Both had small sample sizes — 62 and 389 respondents, respectively, but Bowman and Bartlett share the sentiment that one incident is one too many.

maggie.macintosh@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @macintoshmaggie

Maggie Macintosh reports on education for the Winnipeg Free Press. Funding for the Free Press education reporter comes from the Government of Canada through the Local Journalism Initiative.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.