‘Yanked around like a rag doll’

Report details use of restraint against students with disabilities

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 11/06/2020 (2010 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Some parents say their children were physically restrained to a chair at school, with arm splints and posey cuffs. Others reported their child had been confined to a cinder block-lined closet. In one case, a student came home often with torn clothing, after he had been “yanked around like a rag doll and forced into the quiet room.”

A new report on the use of physical restraint and seclusion of students with disabilities in Manitoba schools details anonymous accounts from parents about their children’s experiences — in certain cases, on a frequent or daily basis.

“One story about the restraint and seclusion of a child with a disability is one story too many,” said author Nadine Bartlett, an assistant professor of inclusive education at the University of Manitoba.

The report, “Behind Closed Doors,” includes insights from 62 parents and guardians who responded to an online survey (July-October 2019) about the practices. Advocacy organizations for Manitobans with disabilities helped distribute the exploratory survey, a classification that speaks to the small sample size of the research.

Adults were invited to participate in the study if their child had been physically restrained or placed in an isolated area for an extended period of time and prevented from leaving the area on at least one occasion during the last three years.

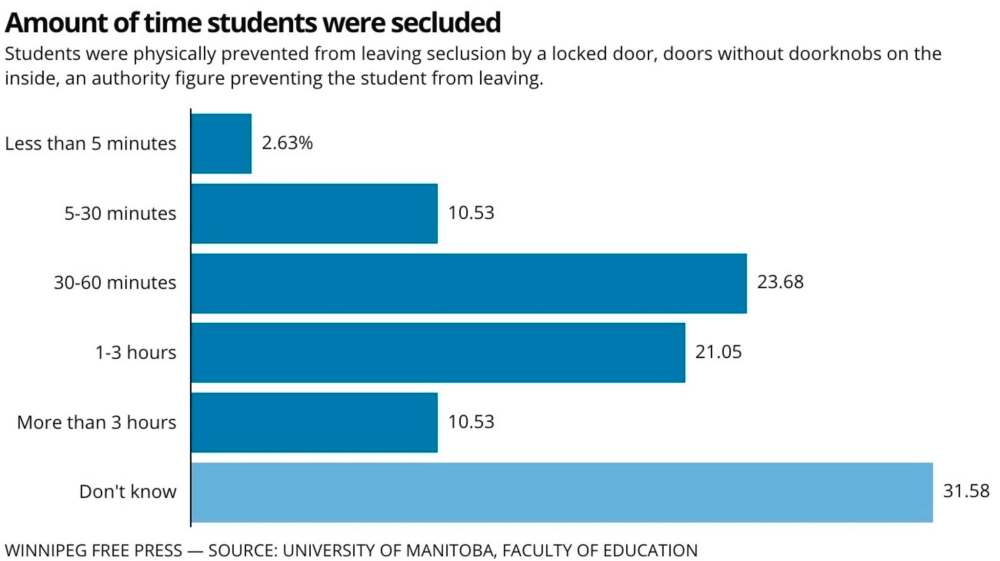

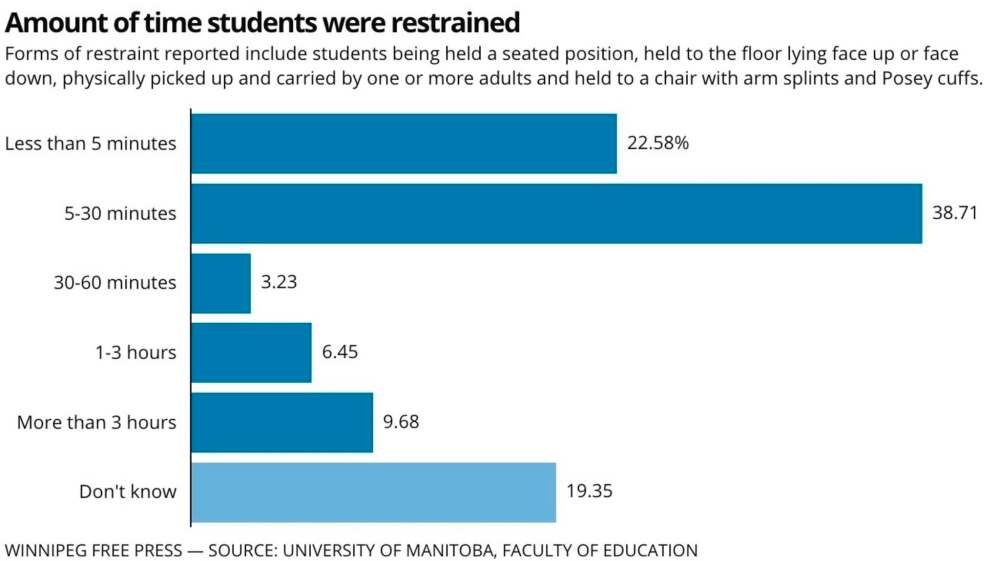

Some respondents answered questions about both practices; 31 addressed physical restraint incidents and 38 submitted responses about seclusion.

Parents reported the use of holding students to the floor lying face-down, being picked up and carried, and being restrained while being forced to walk.

Most restraint incidents lasted 30 minutes or less. Seclusion was reported in varying durations, with some incidents lasting upwards of three hours long.

Among common themes in the report: the use of seclusion, despite not giving consent for its use; isolation in rooms where students couldn’t leave once inside; and rarely being informed about incidents from school administration.

Roughly half of parents said they always or usually received notification from the school after an incident, be it restraint or seclusion. Even then, respondents said it was rarely in a written format, or timely.

“That’s very problematic. There should be same-day, written-reporting as a sort of best practice, because we’re talking about a crisis,” said Bartlett. “If this happens, it should only be in a crisis situation.”

Bartlett undertook the research last summer, in an effort to document practices not tracked on either a national or provincial level. Despite the data desert, she said she knew firsthand both were an issue, having worked in the public school system as a classroom teacher, resource teacher and student-services administrator for more than two decades.

There are currently no provincial educational policies in place that explicitly regulate the use of either practice in Manitoba’s schools; instead, divisions often pay for non-violent crisis intervention training. (Bartlett suggests Manitoba look to Alberta’s model in developing one.)

The report offers six recommendations for the province to address the use of restraint and seclusion: provincial guidelines for practices; standards for seclusion spaces; incident reporting requirements; the use of practices only in crises; the prescription of a standardized training program; and a review of the province-wide practice, once implemented.

“Restraining is not the answer– definitely not the answer — and definitely not locking them down in a room. You just wait it out.”

– Val Surbey, a parent and board member at the Manitoba Down Syndrome Society

After re-reading the report Thursday, Janet Forbes of Inclusive Winnipeg said she felt an “overwhelming sadness.”

“When there’s a crisis, there may need to be a safe place for someone to go to, but there needs to be a lot of guidelines around it so that a kid is kept safe,” said Forbes, executive director of the organization.

She said there’s a need for spaces where students can go to calm down — oftentimes, called sensory, blue or calming rooms — but the misuse of these spaces for forced seclusion is unacceptable. Students experience lasting trauma after being isolated in them, Forbes added.

Ninety-seven per cent of respondents to the report indicated their child experienced emotional trauma as a result of seclusion, while 15 per cent said their student suffered pain or physical injury, including bruising, head injuries and pinched fingers.

Val Surbey, a parent and board member at the Manitoba Down Syndrome Society, is in favour of school staff using non-contact approaches to deal with student outbursts. Surbey’s four boys have all graduated from Manitoba’s education system, but she said none of their individual education plans allowed for restraint or seclusion.

She said Thursday she doesn’t believe any of them experienced either, since she was never informed. If there was a situation where de-escalation was required, she asked to be called to the school.

“Restraining is not the answer — definitely not the answer — and definitely not locking them down in a room,” she said, adding a hold can put both a student and staffer at risk of serious injury. “You just wait it out.”

The province did not provide comment on the report.

maggie.macintosh@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @macintoshmaggie

wfppdf:https://media.winnipegfreepress.com/documents/Behind+Closed+Doors+Magazine+Final+PDF.pdf|Read the full report:wfppdf

Maggie Macintosh reports on education for the Winnipeg Free Press. Funding for the Free Press education reporter comes from the Government of Canada through the Local Journalism Initiative.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Friday, June 12, 2020 8:11 AM CDT: Corrects that most restraint incidents lasted 30 minutes or less. Seclusion was reported in varying durations, with some incidents lasting upwards of three hours long.

Updated on Friday, June 12, 2020 11:16 AM CDT: Adds full report.