Solitary silence, collective roar Money, power effective in muting individual sex-abuse victims' voices, but in #MeToo era there is strength in numbers

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 06/03/2020 (2104 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

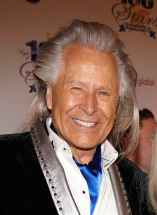

The man has money, almost beyond imagination. The man understands that wealth of that level is equivalent to power, because it can buy raw intimidation. That kind of money can afford to be shameless. It can pay for whole armies of lawyers to sow lawsuits. It can find its way into bank accounts linked to key politicians.

So there is nothing the man can’t buy, including — at least, for a time — his privacy from the eyes of justice, because justice of any kind depends on a counterbalance of power, and his wealth weighs heavy on the scales. He gets all that he wants: the airplanes, the yacht, the lavish estate on a lush private island.

Then his appetites turn towards women, or sometimes even girls. They are much younger than he is, and they have much less than he has. They can’t afford lawyers. They can’t afford insulation from the storm. So when they are hurt, when he or others in his orbit hurt them, they are left clutching that truth with few places to turn.

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before.

This is not a new story. This one is very old, both in the broad strokes and the particulars. Rattle off the names so accused in the last handful of years alone: Epstein, Weinstein and, now, Peter Nygard. This is not close to the end. You can bet there will be many more, before the reckoning with powerful men who allegedly abuse is done.

Correction: it will never be done, because the conditions that allow it to flourish will continue unabated. The shape of the latest allegations to coalesce around Nygard is proof of concept. For decades, reports of his private activities have been widespread and consistent, subject to various media reports, but nothing ever quite stuck.

This has gone on so long. In 1980, the Free Press reported that Nygard had been charged with the sexual assault of an 18-year-old woman; the charge was dropped when the complainant declined to testify. (Not uncommon in sexual assault cases, especially in previous decades, as the balance of power can be slanted against the accuser.)

In 1996, a former employee in Los Angeles launched a sexual harassment lawsuit against him, which was dismissed. In the late 1990s, former employees filed three sexual harassment complaints against him to the Manitoba Human Rights Commission, alleging incidents ranging from fondling himself in his office to urging skinny dipping.

Those cases were later settled out of court, as were others relating to personal and workplace conduct.

There have been attempts to more fully pull back the veil from what happened at his Bahamas estate. Back in April 2010, the CBC’s Fifth Estate ran a deep investigation into his treatment of employees, which included shocking descriptions of abuse and sexual harassment of workers from a variety of sources.

Nygard first sought legal help to stop the story from being broadcast. When it aired, he sued for defamation; that case is still before the courts and subject to a publication ban.

Somehow, through it all, he remained in control of his fate. In Winnipeg, he even became a punchline of sorts, a caricature of the flamboyant apparel tycoon so out of tune with the blue-collar mores of the city where he headquarters his company. The man on the billboards, the eccentric, the joke.

Which makes it all the more notable now that something finally seems to be shifting. Last month, 10 women filed a lawsuit against Nygard in U.S. federal court, alleging extensive acts of sexual assault and sexual trafficking. A week later, Nygard stepped down from the helm of his company after its New York office was raided by the FBI.

The story keeps growing. In the Bahamas, Free Press journalist Ryan Thorpe met with seven women who gave chilling accounts of being sexually assaulted by Nygard; six were minors at the time of the alleged attacks. One of them also said she regularly dropped off cash payments to Bahamian police and politicians from Nygard.

Through his lawyer, Nygard has vociferously denied the allegations, which have not been proven in court. He alleges it is being driven as part of a long-running dispute between his billionaire neighbour in the Bahamas, that the women are being paid to fabricate the allegations.

The public can judge whether that holds water. It would have to hold a lot. Because the stories aren’t just trickling out now, as they did for decades; now, they are pouring. As of this week, at least 50 women have alleged sexual abuse linked to Nygard, and there are criminal investigations underway in the Bahamas and New York.

As the wheels of justice turn, there is little the public can do but watch and wrestle again with the same ages-old question: if the allegations are true, what must change so that victims and the public are not so defenceless against influential people who abuse? What must change, to allow justice to take root in the estates of power?

Right now, it seems, the most effective solution has been unification. If victims can connect with each other, and find in their common experience the strength and support to face their abusers together, they stand a better chance than when they feel they are living with the scars alone. Sometimes, it takes one person to start it.

The public, too, plays a role. The Me Too movement has been an imperfect corrective to the lack of justice that for so long has plagued victims of sexual assault and abuse; but it has also been remarkably effective at supporting those who step forward, driving investigations and directing the fire of public outrage onto the abusers.

There will need to be other solutions, ones that empower victims and protect them from the threat of their abuser’s power. Ones that don’t require decades to connect enough victims with each other that they can find more safety in their numbers. Ones that don’t leave young and poor women as easy prey for those who pull the strings.

This much is certain: there are many men out there now who have learned their wealth can buy everything. One day again we will review a trail of abuse that lasted years or decades, and wonder what harm could have been prevented if justice had moved faster, if public sanction had hit harder or sooner, if victims had truly been heard.

The frustration is that we know that day will come. The flicker of hope is that, when it does, there will be a little bit more justice in it than each time before.

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.