Record-keeping reckoning Faith groups struggle to maintain archival collections

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 14/02/2020 (2124 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

When churches close, congregations are faced with many questions: What happens to the staff? What happens to the remaining members? What about the building?

One question near the bottom of the list may be: What happens to the records?

While it might not be top of mind for churches that are closing, it’s at the forefront for archivists in Winnipeg. With many churches considering shutting down in the next few years, they wonder: Where is all that stuff going to go? And who will pay to process it?

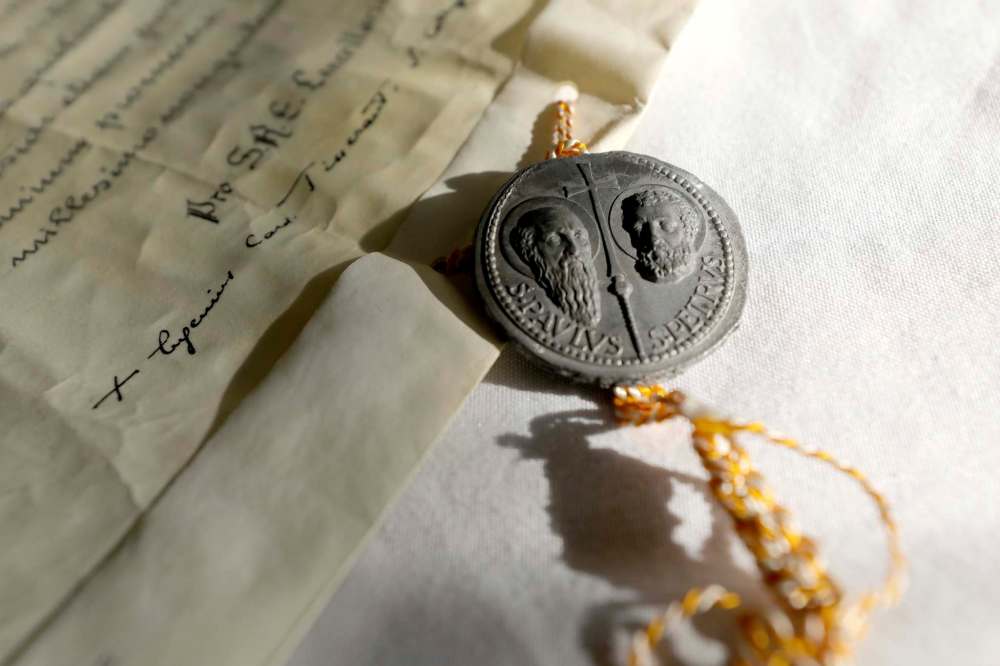

Religious archives can be a diverse respository of faith history. They can include everything from baptismal records to church council minutes; sermons; service bulletins; photos; recordings; letters, diaries and memoirs; church property records; sheet music and hymnbooks; artwork; and, in some cases, sacred items and religious regalia.

“Congregations are closing regularly, and their archival records are coming to us at an unprecedented rate,” said Erin Acland of the United Church of Canada archives at the University of Winnipeg.

“As congregations close, the need for archives increases, but the funding for them diminishes.”

For Acland, the problem is not only space — the United Church archives ran out of on-site storage space in 1996, and now stores about half its collection off-site — but also funding to deal with the new materials being dropped off.

She’s not alone; other religious archives in the province are facing the same problem as churches close or individuals downsize.

“For decades, archivists have made do with very limited funding and support,” she shared. But making do is no longer good enough “to solve some of the big issues we’re facing.”

Something similar is happening at the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Winnipeg, where Tyyne Petrowski is the director of archives.

“Space is always a concern for us,” she said, noting some of their collection is also stored off-site.

“It would be much better to have everything on-site, if only we had the space and proper storage conditions to keep them here.”

Any time people want items stored off-site it not only takes more time, she said, but the archive needs to pay a fee.

Added to her challenges is what happens when religious orders close; some may send materials to mother houses in other provinces, but others will expect the Winnipeg archdiocese to look after their records.

At the Jewish Heritage Centre, executive director Belle Jarniewski also struggles to find space for the many items in the collection — more than 70,000 photos, 1,300 sound and moving image recordings, 1,000 textual records, 200 bound volumes of newspapers and more than 4,000 artifacts.

“The urgency is great,” said Jarniewski of the crisis facing her archive. “Some items are becoming very fragile and we can no longer make the originals available to the public. And with an aging population we receive donations of various items all the time.”

To meet the challenges, the centre has launched a $2-million fundraising campaign to hire a full-time archivist, make sure the materials are stored properly, and digitize the collections.

For Jason Zinko, bishop of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Canada’s Manitoba and Northwestern Ontario synod, archives are an ongoing issue.

As congregations close, he says there will be a significant challenge in archiving materials since congregations approach record keeping in different ways.

“We can’t anticipate the kinds of material we could receive, or how well it is documented,” he said, adding they currently store items in three locations.

One thing they likely couldn’t take, he explained, would be furnishings and other objects that are significant to closing congregations — something he knows would be disappointing for many.

“I hope that we will be able to strike a balance between what is practical and what allows us to remember and tell our story,” he said, adding finding money to do proper records management and cataloguing of the collection is a challenge.

For him, “maintaining a historical record of who our church has been and how God has been active in our congregations over the years is incredibly important,” he stated. “It is a significant way for us to pass on the story of our ministry with God in our communities.”

Church closures are not a big concern for Conrad Stoesz at the Mennonite Heritage Archives; his challenge is all the material coming from individuals.

“For the first time in history two generations are downsizing,” he said, noting boomers are getting rid of stuff by moving into condos or apartments while their parents are doing the same as they move into assisted living.

He has enough space right now. “The big issue is humidity and proper temperature-controlled environment to store and catalogue things properly,” he noted.

At the same time, he noted a lot of new digital content is being created that needs specialized tagging and cataloguing — along with the expensive software that can access it.

For Gordon Goldsborough, president of the Manitoba Historical Society, the situation facing archives in the province is fast becoming a crisis.

“Archives are not a high priority for anyone these days,” he said. “That really worries me. So many things could be turned away.”

He wonders if religious and other archives need to work together — maybe find a building they can share.

Faithful preservation

Erin Acland is the self-described “keeper of the archives” for the United Church in Manitoba and Northwestern Ontario. She provides a glimpse into the challenges she faces preserving and providing archival material for people in Manitoba and across Canada.

“I only work part-time, 21 hours a week. Several years ago, in less busy days, it was determined that two full-time staff were needed. Not only have I been doing my best to do a two-person job in a quarter of the time, but the backlog of work not done continues to build every year.”

Erin Acland is the self-described “keeper of the archives” for the United Church in Manitoba and Northwestern Ontario. She provides a glimpse into the challenges she faces preserving and providing archival material for people in Manitoba and across Canada.

“I only work part-time, 21 hours a week. Several years ago, in less busy days, it was determined that two full-time staff were needed. Not only have I been doing my best to do a two-person job in a quarter of the time, but the backlog of work not done continues to build every year.”

The problem of staffing is not new. We’ve never had enough staff, but the problem is getting worse. In a few cases, records donated more than 35 years ago (longer than I’ve been alive) remain unprocessed. Time and time again I’ll process a collection, and another one will arrive that afternoon. Processing records is a Sisyphean task.

External government and private grants take a lot of time to apply for, are project-based — not that helpful when one requires long-term sustainable funding. They are also extremely competitive, and few in number. Every time I apply for a grant, I gamble with my time and money.

Fulfilling reference requests, and managing expectations of users, is a challenge. I receive about 500 research requests each year with the vast majority requiring at least one hour to fulfil, and some considerably more. While many genealogists contact me, I also receive requests from academics, Indigenous communities, lawyers, and from the United Church itself.

The most common request I fulfil is a search of our baptism and marriage records. These are often requested by the people named in the record and are required for legal or spiritual reasons. Most requests are fulfiled within three weeks.

If researchers want to visit in-person they must make an appointment for when I am physically on-site. With half of our collection off-site, I need about 48 hours notice to order a box to be delivered.

The United Church also continues to create new records. In an increasingly complicated information world, archivists often have to act as record managers. This comes with its own challenges and time needs.

Digital records also must be preserved and made accessible. Digital infrastructure must be created and maintained so that digital material can be preserved intact in a world where technology can become obsolete within two years. Metadata (descriptions about digital records) has to be created and embedded. In effect, a second parallel archive must be constructed to care for digital records alongside analog.

The care of digital records is far more complicated and complex than can easily be summed up. Expensive software is being considered to help the issue, but it is yet one more financial and staff burden to manage.

The church cares deeply for its archives and is determined to preserve and enable accessibility to its records, but ultimately the Church is not in the business of archiving. Hard financial choices were made in the past and will continue to be made in the future.”

“Why not the Bay?” he asked. “Why not build a world-class archive there? It’s structurally solid, large and in a central location. What better place for an archive than a heritage building?”

For that to happen, he said, the provincial government would need to show leadership.

Another option is to re-purpose a church that is closing, he noted — something happening in Kingston, Ont. where the local Roman Catholic archdiocese and two religious orders are turning a closed historic church into a shared archival centre.

But with all the challenges facing many denominations, he knows religious groups are in a tough spot. “Archives aren’t essential to their core mandate,” he acknowledged, noting there are many other frontline ministries they need to support.

Even though things are dire, Acland hopes there can be a resolution to the challenges facing religious archives so they can remain accessible to the public.

“I cannot understate how incredible our archival collection is,” she said, noting it holds unique insights into the history of the people from over 600 communities in Manitoba and Northwestern Ontario since 1838.

Added Petrowski: “It’s easy to say that you can’t afford something, until you need to trace something for legal, historical, cultural purposes. Then, in those cases, you can’t afford to not to have an archival program.”

Faith@freepress.mb.ca

The Free Press is committed to covering faith in Manitoba. If you appreciate that coverage, help us do more! Your contribution of $10, $25 or more will allow us to deepen our reporting about faith in the province. Thanks! BECOME A FAITH JOURNALISM SUPPORTER

John Longhurst has been writing for Winnipeg's faith pages since 2003. He also writes for Religion News Service in the U.S., and blogs about the media, marketing and communications at Making the News.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

The Free Press acknowledges the financial support it receives from members of the city’s faith community, which makes our coverage of religion possible.