Milder winters raise ice-road anxiety in remote Manitoba communities

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 17/12/2019 (2184 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

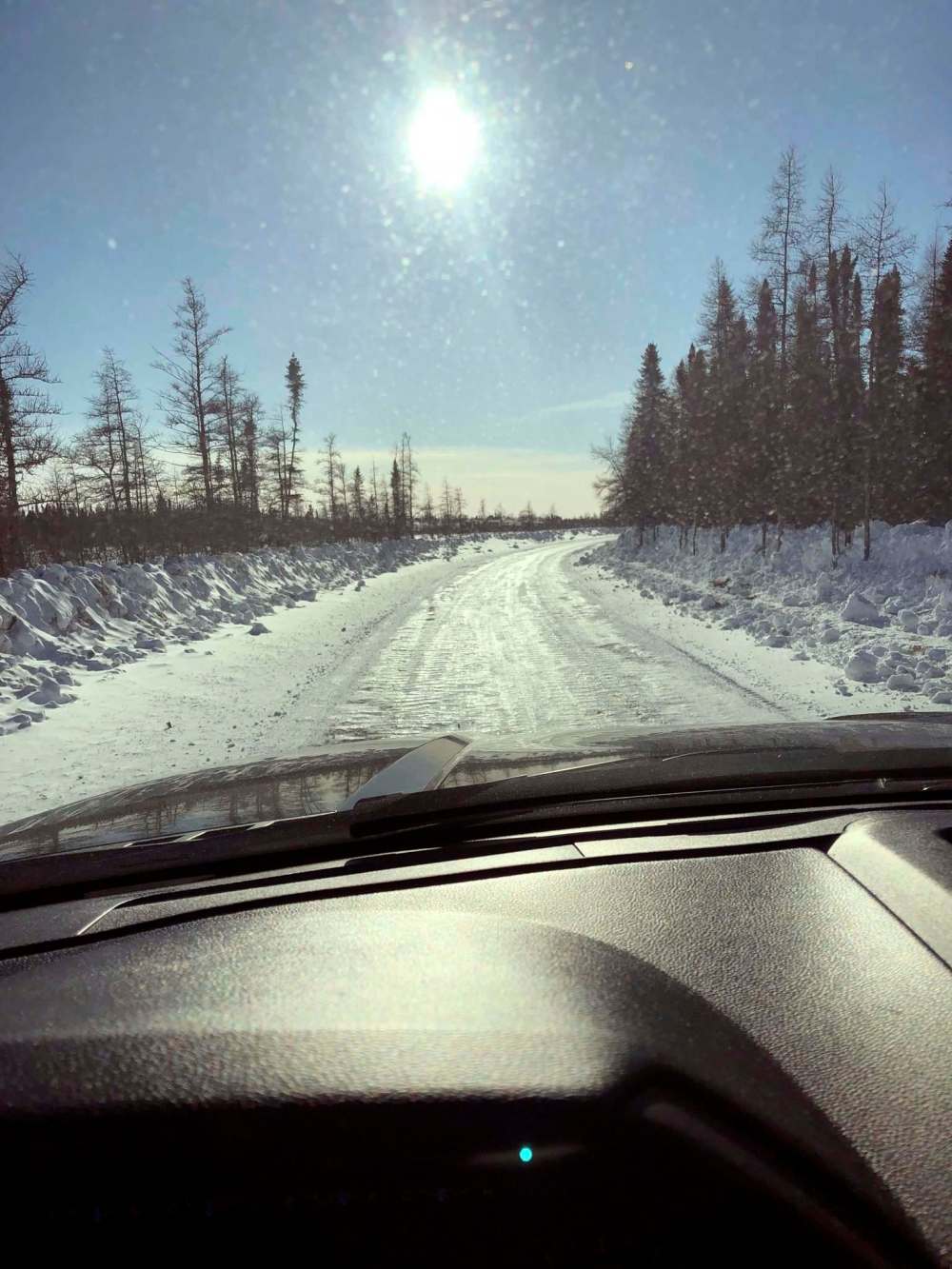

As climate change makes Manitoba winters increasingly unpredictable, leaders in remote First Nations are crossing their fingers, hoping for a long-lasting winter road season so residents can travel and essential goods can be transported via truck.

“Every year, you worry: ‘If they’re not done this year, then what?’” said John Clarke, chief of Barren Lands First Nation. “It is our lifeline. If there was no winter road, then we’d have to fly everything in and we could never afford that.”

Clarke, 48, said the community used to be able to rely on some roads opening in mid-December and remaining accessible for three months. The network has yet to freeze for the season; he expects it’ll be between early to mid-January, the new normal in recent years.

Melting glaciers and rising sea levels have become sure signs of the real impact climate change has on the planet — but a group of researchers recently put a microscope on the way warmer weather affects fresh-water ice on lakes and rivers in the northern hemisphere.

A new scientific report published in Limnology and Oceanography earlier this autumn notes lakes and rivers in the world’s cooler climates are freezing later and thawing earlier. The report found that over time, warmer temperatures have caused delays to winter ice road opening dates and led to cancellations of cultural events that rely on frozen conditions.

“I’ve been interested in changing ice as a way to understand changing climate but I didn’t think about how many millions of people rely on ice every winter… for transportation, recreation, food. It’s really part of our daily winter lives,” said Sapna Sharma, an associate professor of biology at York University in Toronto who co-authored the report.

Frozen ice plays an especially important role in remote communities such as Barren Lands, which rely on frozen lakes, rivers and creeks to make up their winter transportation networks — an alternative to pricey air travel.

Sharma and her colleagues looked at the St. James Bay network in northern Ontario. Comparing opening dates and winter air temperatures, the researchers concluded the ice road season can be cut by as much as three weeks during warmer winters.

“Northern communities, for example in Ontario and Manitoba, require these ice roads. A three-week shorter season means less access to resources — food, supplies — but also, it decreases social network and that can have a huge impact on mental health,” Sharma said.

The winter road network in Manitoba allows for trucking access to remote First Nations, as well as inter-community travel. It serves 23 communities, located across northern and eastern Manitoba.

Four of the communities are still reliant on the roads for the diesel loads that feed electricity-providing generators.

The roads are open during a brief period of about eight weeks from mid-January to mid-March, although weather conditions can shorten or extend the season by as much as two weeks, the province says.

“There have been anomalies over the past 10 years; however, records indicate no significant shift toward shortening of the winter road season based on weather,” a provincial spokesperson said in a statement.

The spokesperson said that Manitoba has realigned approximately 400 kilometres of winter road from lakes and rivers to overland areas in order to create a safer and more reliable network.

The average winter road season is 60 days, the statement said.

But members of northern First Nations are skeptical of that claim.

“The seasons are getting a lot shorter now. We’re lucky we can get about a month-and-a-half of winter roads now. It’s all depending on temperatures and everything. The weather’s been crazy,” Clarke said, adding he has brought his concerns to both the federal and provincial governments.

Aside from getting critical supplies for infrastructure building and food, Clarke said the roads ensure people can socialize with other communities and attend the beloved northern winter carnivals.

“It provided some freedom, that’s how I felt — like I’m connected to the world, to the highways,” said Clyde Flett, a member of St. Theresa Point First Nation who moved to Winnipeg from the remote community located 610 kilometres north of the Manitoba capital 10 years ago.

Flett said the roads allowed him to visit neighbouring communities to attend hockey tournaments.

He said he worries about being able to drive along winter roads, his preferred form of transportation — a one-way plane ticket can cost about $360 — to visit family and friends back home in the future because of the changing climate.

maggie.macintosh@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @macintoshmaggie

An airborne alternative

A longtime champion of airships is urging the province to get on board with the mode of transportation so it can become a future method of delivering goods to remote communities.

For years, Barry Prentice, a member of the University of Manitoba’s Transport Institute, has been touting cargo airships as a carbon-neutral option, which is powered by hydrogen, to transport items to First Nations in northern Manitoba during the wintertime.

Prentice built a prototype, but in 2016 a storm destroyed his one-of-a-kind research hangar. Now, his team is rebuilding. They are currently working on gas cells that fill airship structures so they can fly.

Investment into the industry is required for serious takeoff, he said.

“The government has to take the leadership on this because they’re the ones who control the sky. They can’t just be AWOL and expect things are going to fix themselves,” Prentice said, adding he’s among those concerned about how climate change will affect future winter road seasons.

Prentice believes airships will be flown as cargo vehicles in other parts of the world within a couple of years.

In a statement, a provincial spokesperson said the government “remains open” to learning about new transport technologies to make northern supply chains more efficient.

The spokesperson added the government would be pleased to discuss the option further “on the basis of there being robust, near-market-ready business and feasibility plans, with proof-of-concept demonstrations established.”

— Maggie Macintosh

Maggie Macintosh reports on education for the Winnipeg Free Press. Funding for the Free Press education reporter comes from the Government of Canada through the Local Journalism Initiative.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.