Who tells me the plane is safe now?

The strongest person I've ever known helped me find myself countless times with love and patience, without judgment; and now I've lost my dad

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 02/11/2019 (2232 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The greatest adventure my father and I never have begins one afternoon in August over smoked salmon benedicts, served to us by a waitress at his favourite cafe who, it turns out, knows him by name, which makes me stifle a laugh. If three things are certain in life, they are death, taxes and that everyone in Winnipeg seems to know Dad.

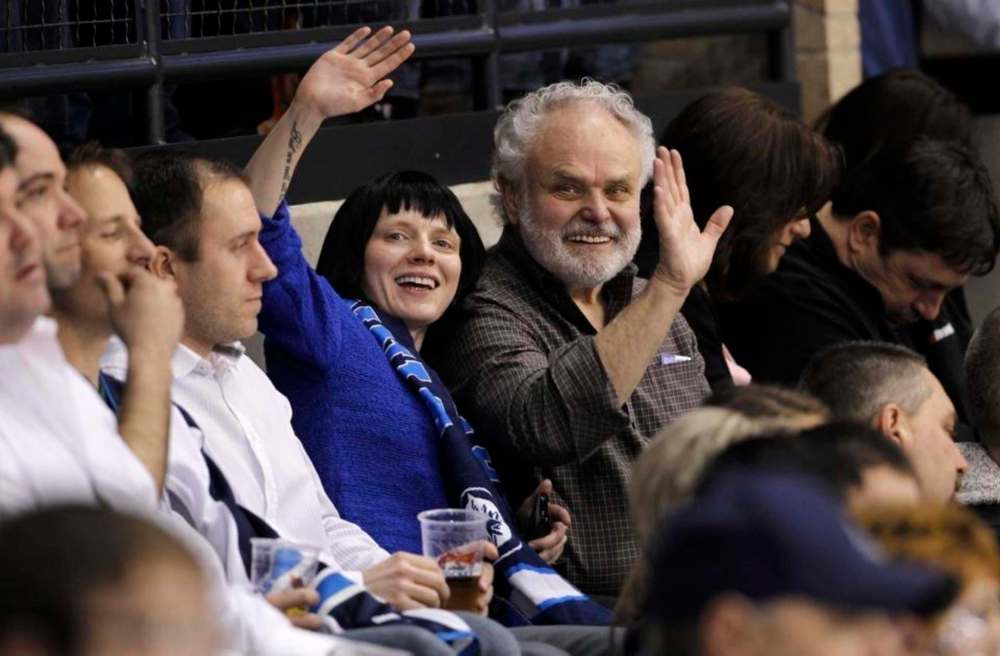

Over the years, this pattern of recognition became family lore, stories told and retold over holiday dinners. Once, we were at an airport in Denver when a voice rang in our direction: “Hi, David!” Or, we were in line for a Disneyland ride when it happened: “Hey, Dr. Martin!” Everywhere we go, he is known, and I tease him about it sometimes.

“I can’t help it!” he protests. “I’m a likable guy!”

So here we are, forks full of hollandaise at a place where the staff, no surprise, know him by name, when he makes his surprising suggestion. The idea, he begins, came from his “foga” friends, a troupe of self-proclaimed “old fogeys” who meet each week to do yoga and lunch, and also, apparently, to put ambitious plans in his brain.

The two of us, he proclaims, should apply to compete as a team on The Amazing Race Canada.

Two months before this conversation, my dad turned 80 years old. He’d been looking forward to the milestone for ages — mostly, he’d say, so he could savour the surprise in people’s eyes when he told them. He doesn’t look 80, they’d say, assessing the spring in his step and youth in his face; he doesn’t feel like it either, he’d reply.

So now, he imagines the reactions as he dashes across Canada on a reality-TV competition. He thinks, though he hasn’t checked, that he might be the oldest contestant ever to be on the show, which he likes, and besides, there’s something so right about the idea of the two of us embarking on some epic adventure.

“I just think I could do it,” he says. “Wouldn’t that be something, us flying around together?”

In truth, the fact that I can is a gift from my father. Shortly after my 18th birthday, I am gripped by a fear of flying so severe it will keep me grounded for more than 10 years. When circumstances finally force me back into the sky, I spend weeks preparing for the flight, confessing my fears to my dad on long, aimless drives.

The plane won’t crash, he tells me. It won’t break apart in flight. It also won’t explode, it won’t run out of gas and it definitely will not simply fall from the sky, unbound by the dark sorcery I am convinced holds it 35,000 feet in the air.

He never loses patience with my questions. In time, with his gentle therapist’s touch, he begins to pry apart the fear. When I envision the flight, he asks, what happens? Truth is, I only ever picture it ending one way: with a fiery plunge into a farmer’s field or a shower of debris over the nearest ocean.

This, my dad explains, is part of what’s holding me back, and not only from flying. My inner world, I will learn, is a place blighted by endless catastrophes, where mundane events meet terrible ends; plane crashes, yes, but also failure, humiliation, rejection. I am battling through life in a constant state of self-preservation.

So as we talk, he guides me through how to take control of my imagination. He shows me how to replace the vision of that fiery plunge with one closer to what will actually happen: the plane will go up, then it will cruise at the same altitude for some predetermined and reliably boring length of time, and then it will land.

Of all the things I learn from my father, this trick is among the most pivotal. I learn how to visualize what is real, to shake me loose from the grip of my fears. Before flights, before meetings, before the difficult calls that journalists must make, I settle my nerves by rehearsing in my mind how they will unfold.

Still, even as my fear of flying fades, one part of this process crystallizes into a ritual: I always text my dad when I’m boarding a plane, and he replies that everything will be fine. Nobody worries about me more than my father, so if his heart doesn’t seize up when I’m riding the sky, then mine shouldn’t, either.

Besides, after a while, the texts become just another one of the little jokes that we have.

This is a picture of my plane, Dad. It looks OK, right?

It looks OK and very, very safe. You’re not going to crash, I promise. Love you.

Now, I visualize us flying around the world together. Father and daughter, embarking on our greatest adventure, and maybe even our last big one together. I research how to apply for The Amazing Race. I visualize the two of us, full of smiles, talking to the cameras as we dash between destinations.

I plan to tell him all of this over brunch two weeks later, but he texts to postpone those plans for the next day. A flare of seasonal allergies, he explains, and we’ve read that they’ve been especially bad this year, due to climate change. It’s OK though, he adds: a little breathless, but as long as he rests, it’s not too bad.

“Annoying, but not scary,” he texts.

Dad never puts burdens on anyone’s shoulders that he doesn’t think they can carry.

● ● ●

There’s a certain island in the middle of the Whitemouth River. It isn’t much, just a half-marble of green grass, but my dad feels an energy there he can’t quite explain. He calls it his “magic island,” and he takes everyone he loves there sooner or later, guiding the canoe past beaver dams and the babbling mouths of small rapids.

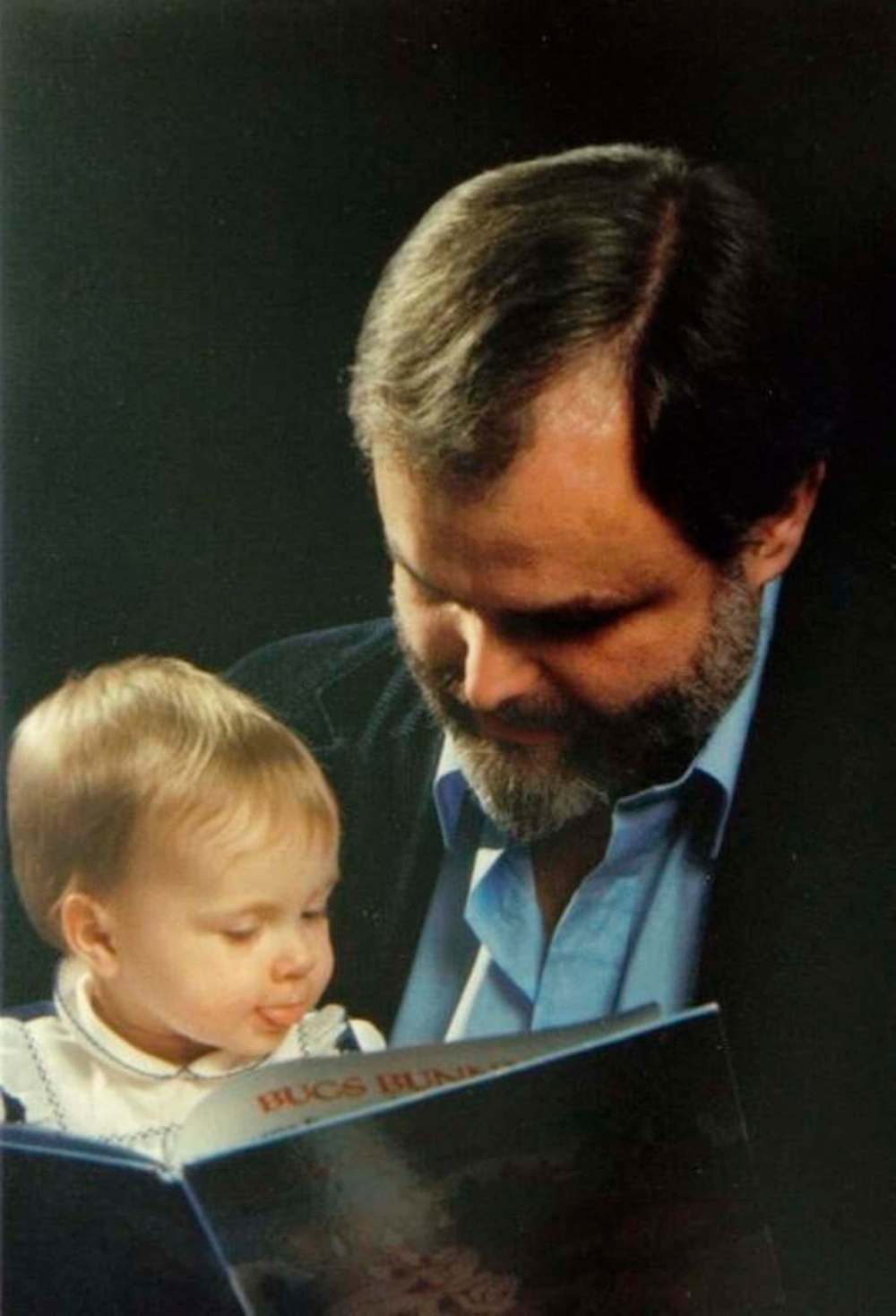

The first time he takes me to the island, I am barely to his knee, and barely old enough to remember. We spend the night there, near the water, toasting marshmallows and pointing out stars. It is around this time that I begin asking a strange question, one I will repeat for most of my childhood: when is he going to stop being my dad?

“I will always, always be your dad,” he says, trying not to let his worry show on his face.

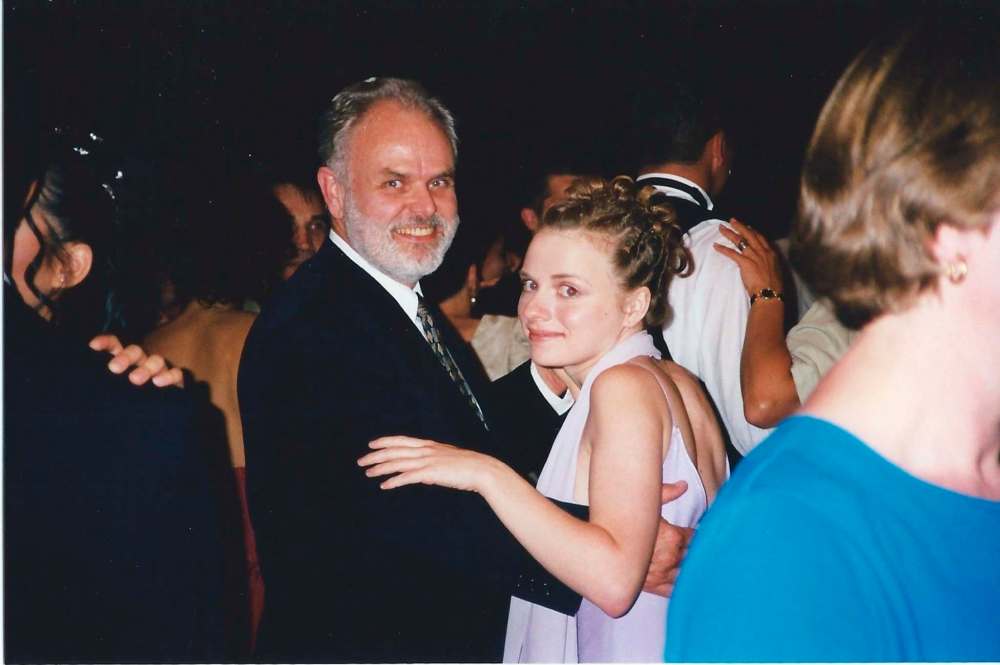

The truth is, I was not born my father’s daughter, but rather made, a bond forged by the stroke of a social worker’s pen three days after I entered the world. When my parents take me home, freshly minted the youngest of their six children, the social worker casually tells Dad to call back if it doesn’t work out.

They say blood is thicker than water, but it’s hard to say where paperwork fits in.

Still, despite a lack of shared DNA, there is no doubt I am my father’s daughter. We even have the same eyes, his friends say, the same crystal-blue. Mine don’t dance like his, though. They don’t twinkle when my lips are tickled by the start of a joke, or when I first spot the familiar face of someone I know.

The view of my childhood is the view from his shoulders. It’s from that vantage that I see my first concert, my first glimpses of nature and the old peace marches through downtown streets. In the summer, we pull on rubber boots and chase frogs by the river, or feed grass to the sheep the University of Manitoba then keeps on campus.

Every night we’re together, he tells me a story. The most popular of these is one he makes up in his head, a fantasy about two sisters who go on magical adventures. He keeps this serial running for years; sometimes, I fall asleep in the middle. He starts taping each session so he can remember what I missed, and what exactly he said.

He never yells at me, except once, in a hotel room in Jasper. My teenage sister and I are huddled under a blanket, smothering giggles over a late-night game of Go Fish, when suddenly, Dad bellows from the next bed over: GET TO SLEEP, YOU KIDS…

“OK, OK hold on,” he says, chortling. “I don’t think I’m being fairly represented here.”

No you yelled! You screamed like this: BWAAAAGHHHH! Kristen remembers it like that too.

“I sense that I’m being ganged up on here.”

OK, so he never yells at me, really. The truth is, he can’t stand to see me in distress. Like the time we are canoeing in Lake of the Woods, fishing off a boulder that dipped into the water. When I pull my fish out, its flailing strikes me as a horror. I start crying, begging him to let it go, and my dad, panicked, kicks the fish back into the water…

“Hold on, hold on. Let me defend myself here. I didn’t kick the fish. I nudged it, with my toe.”

No you did! I saw it! You wound up your leg and walloped it into the air.

“I think that time and the trauma of this incident has coloured your memory, somewhat.”

For some reason, I think of all this the first night, in the emergency room. He waves me through the curtain, lying in bed, hands folded calmly in his lap. He is wearing an oxygen mask that almost, but not quite, hides his broad smile.

“I’m in the best place I can be,” he says brightly, between wheezing breaths.

There is a machine next to his head flashing ominous numbers. “Watch this,” he says, and then squeezes his eyes shut and huffs through the mask, taking gulps of pure air. The number on the screen that tracks the oxygen level of his blood begins to tick up: it’s supposed to stay above 90, and now it’s at 94, 95, 96…

The nurse purses her lips. “Don’t hyperventilate yourself,” she says, drily.

Dad slumps into the bed, briefly deflated by his failure to impress her, but then the twinkle creeps back into his eyes.

“The weird thing about this,” he says, in a tone of mock disbelief, “is that it turns out I’m not invincible.”

I gather all my visions of us flying around on TV and, with a knot in my heart, shove them deep down inside.

● ● ●

My father’s life transfixes me, because it seems fictional. He was born in the summer of 1939, entering the world at the exact time it careened towards disaster, but the war never found him in the cozy Michigan town where he grew up. Nobody too close to him fought in the war, and he remembers little about rations.

But he does remember he had a Red Flyer wagon, and a Schwinn bike. He had a treehouse, and a dog named Skippy that knew how to climb the ladder into the treehouse, where they would curl up together for hours, eating freshly baked cookies and reading dog-eared Captain Marvel comics.

The America of my dad’s youth stretched out in wide horizons and long afternoons. An idyllic life, a precise middle American dream that, though romanticized by any number of painters and politicians, only ever belonged to a small handful of people who history so favoured. An apple pie life, a childhood by Norman Rockwell.

So I collect stories of his life like pearls salvaged from some unknowable deep. I ask him to tell me again about the years when baseball on the radio gave way to the razzle-dazzle of colour TV. I memorize the misadventures he had when he was 14, and hitchhiked to Texas to go see a girl he met at Bible camp…

“Wait, wait. It wasn’t Bible camp. It was Methodist summer camp.”

Is there a difference?

“Never mind, go on.”

As a boy, Dad thought he would grow up to be a minister. But then he read about hypnosis, which seemed cool to a teenager, so he went off to study psychology at Albion College, where he met Jimmy Hoffa at a parent tour night and briefly dated his daughter…

“OK, OK, hold on. Somehow this story became that I dated his daughter. I never dated her.”

Didn’t you? I swear you told me you went out with her.

“Well, I might have left the building at the same time as her once, and then I could say: I went OUT with her.”

That’s a terrible joke, Dad.

“Yeah, but a part of you kinda liked it.”

OK, so he didn’t date Jimmy Hoffa’s daughter, but he did discover he had a gift for therapy, a knack for making people feel they could trust him with their most painful secrets. And being a clinical psychology professor is sort of like being a minister, anyway; he preaches to his flock. He spreads the salve of compassion.

In 1969, he moves his young family north, lured by the hope of a calmer nation, and by the chance to help build the clinical psychology program at the University of Manitoba. Three kids become six and his professorship becomes tenured. He wins awards for his teaching and his life settles into a joyful rhythm.

Do you ever realize how lucky you are, Dad?

“I am lucky. Unbelievably lucky.”

We would puzzle this out for hours, the mystery of luck. The fact that, by virtue of random chance, and by virtue of being a white man at a time and place when that was a particularly auspicious thing to be, he had a path laid out to this blessed life, where others struggled just to find room to breathe.

This infuses my dad’s view on the world. He never forgets it. It shapes his values, which he lives by example. He judges no one, except politicians. He cares about the environment, about climate change, about everyone who is hurting more than he is. We spend hours talking about how to make the world a better place.

By the second week in hospital, my dad’s room in the intensive care unit is packed with visitors. “Most popular guy in ICU,” we giggle, which makes it feel safer. He can’t talk anymore, owing to the ventilator that is helping him breathe, but his eyes still dance with mischief and his eyebrows and hands translate his humour.

It’s almost time for his exercise, the nurse tells him.

Lying in bed, with tubes in his arms and tubes down his throat and a tube piercing the skin of his neck, Dad rolls his eyes and perks his index fingers. He flicks them up, and down and then up again, a tongue-in-cheek fitness regime for his digits. For a few moments, a chorus of chuckles drowns out the beeping machines.

I visualize the photo we’ll snap together when he walks out of this place. I picture the wet snow of late October, and the way I’ll nestle under his shoulder. I rehearse how I’ll show him the notes he scribbled while he was zoned out on painkillers — “itch in noooose” — and how I’ll tease him about the raggedy letters.

“Don’t give up,” I tell him, on my way home that night. “I know it sucks, but promise me you’ll never give up.”

He squeezes my hand three times, hard, and punctuates this with a thumbs up.

● ● ●

Fathers like projects. It’s a time-honoured tradition, and though my dad is exceptional in many ways, in this he is no exception. He is handy, in a slightly scattered fashion: he invents little machines. He paints my first one-bedroom apartment. He builds a room in his old Wolseley house, a space to see clients.

“I call it my magic therapy room.”

Oh my God, Dad. That’s so cheesy.

“I know, I know. But it just feels so peaceful in there.”

By this time, growing up has washed over me like a tempest. The fragility of my childhood gives way to a storm of adolescence. I struggle to moderate my emotions. There’s a hole in me that nothing can fill, a perpetual ache for a future that never comes, a voice in my head that constantly hisses a mantra of depression.

Not enough, not enough, not enough.

As my life comes undone, my dad makes me his next project. I am a renovation site, held together by duct tape and glue, carefully applied by my father on long, aimless drives. I talk, he listens. I cry, and the warm flame of his voice dries my tears to salt. It is as if he decides that, to keep me alive, all he can do is simply love me enough.

Through it all, his belief in me never wavers. For years, he clips out each story I write, until they pile up so high that even he finally agrees my byline is no longer special. Still, he can’t help but relay remarks he greedily collects from other professors (”Jerry loved your article!”) and I know, over the phone, that he is beaming.

Bit by bit, he teaches me how to stand on my feet. He teaches me how to breathe through the pain, how to reach out for help when the loneliness becomes too much, how not to let it all spin out of control.

In 2017, when I win a National Newspaper Award, he’s the only one I truly want to know, and I call him, breathless, the next morning.

See Dad? It was worth it. Everything you did for me was worth it.

“Oh sweetie, this is amazing, but you know I never doubted it.”

Never? Not even a little? There had to have been a time you wanted to give up on me…

“Not even a second.”

It is then that I think, not for the first time, that I would not long outlive him.

One morning, as I walk with a sister down the ICU hallway towards Dad’s room, another sister intercepts us.

“Can we talk outside, for a minute?”

The hallway lights are wan and jaundiced. The elevator beside the ICU wheezes open and shut as we speak. My sister relays the doctor’s latest report in staccato beats.

Respiratory failure. Not looking good. Very hard to treat.

The elevator slides open, but I turn on my heels and plunge down the stairs. I stagger through the atrium and thrash out the doors, blinking back the wet September air. Outside, I sit in the damp and watch young parents gingerly carry tiny babies to vehicles, balloons blooming from the handles of brand-new car seats.

CONGRATULATIONS! IT’S A GIRL!

I try to visualize life without my father. It looks like a blank page, a grey screen, a desert where nothing can grow. It feels like the black hole that’s opened up in my guts, sucking the whole world inside it, crushing it into dust. All of it, everything in existence, collapsing down on my shoulders, and it all hurts too much.

So I visualize writing this column.

When they tell my dad the bad news, he takes it in stride. He doesn’t want to die, he writes, on his pad of paper. There are still so many things he wants to do: rivers to paddle, books to revise, stories to tell and grandchildren to advise. But he also tells them this: he is not afraid.

He bends, but does not break. It is then that I realize he is the strongest person I’ve ever known.

● ● ●

On the night that will become the night before, I slip into his room and sit, alone, save for the nurse who haunts the edge of his bed. She hovers over the machines like a ghost in blue scrubs, whispering an invocation to protect this sickbed vigil: “Oh, don’t let me interrupt.”

It’s time to come back to us now, I tell him. He’s been asleep for two weeks. First by design, then by some mystery of the mind that doctors cannot explain. I remember what a coma survivor once said, about feeling trapped underwater, a consciousness drifting in an ocean of forever, forgetting which way was up.

Come this way, I say, if you can hear me. This way to come back, if you can. I still need my dad.

No words come back, but the machines beep a lonely response. This one-sided conversation should feel more foreign than it does, but in truth, it was so often like this between us. How many times did I talk, while he listened? How many times did I pour out my heart, expecting only for him to hold what was in it?

So I pause, and gather my thoughts, and I tell him: you don’t have to worry about us anymore. The kids, we’re flung across North America, but we are still in this together. We have group texts and phone calls and we’re holding onto each other. He would be proud of us, I murmur, and we’ll tell him the whole story someday.

His eyelids don’t flutter. His breathing does, shifting in syncopated rhythms. Message delivered, I decide.

The next morning, my brother calls to say… the news overnight… not good, something changed… and now there are family rushing to catch planes. Now each hour opens and wanes as a lifetime and just an instant, as if future spun off the road and crashed into present, scattering the whole of our lives across every minute.

So I wait in the debris field, and I think about all the things I learned from my father. I think about how beautiful life can be when you receive it without judgment. I think about bending without breaking, about gratitude, and about the gift that is caring for others. I think about the incredible luck that laid out the path of our lives.

And I think about fathers and daughters, and about a love written into existence by a social worker’s pen but that, in the end, transcends “before” and “after.” A love tended like a garden, growing more verdant with time and each year that passes, and with each memory sending its roots down into the earth.

I think about new babies in car seats, cradled by anxious parents. New babies breathing cold air for the first time, new families starting their first journey home together. In that moment, I love them so much that my heart fills up.

The doctor tells my sister: it will be any minute.

I visualize frogs by the river, and stories told in the dark and the view from his shoulders. I visualize sad drives on long roads, and folk songs on the stereo and easy laughter. I visualize an island, a half-marble of green sleeping in the ruddy river, and now it’s getting bigger, engulfing my vision, rushing to meet me as I fall from the sky.

You’re not going to crash, I promise.

Now the island is the whole world, and I am inside it. Stone rooted in the middle of the water, pushing back against the current that keeps churning forward, too scared to budge. Trying to silence the scream welling up in my gut and searching for a voice in the grasses, a familiar song of a laugh, chiming in to say what…

“Wait, wait, that’s not the way this story goes. That’s not how it goes, at all.”

Then the phone rings, and the voice I am aching to hear never comes.

● ● ●

David Martin’s celebration of life will be held at 2 p.m. on Saturday, Nov. 9 at The Gates on Roblin. Donations in his memory can be made to the Nature Conservancy of Canada, which supports conservation efforts in the Whitemouth River Watershed, which contains the magic island that Dad so loved.

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.