Thanks, Dad

Free Press staff recall memorable advice from their fathers

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 16/06/2017 (3103 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Father’s Day is Sunday, and to celebrate, we asked a handful of Free Press staffers to write about some advice — or “dadvice,” if you will — their fathers have doled out to them over the years.

As it turns out, it seems all of our dads offered up similar tips — find a job you love, find people you love, be smart with your money — but the other common thread between many of the submissions (which is also quite funny) was most writers did not include the name of the father they were writing about — he was just referred to as “Dad.” I’m not sure what that says about how we see our parents, even as we become adults, but it’s endearing regardless.

So, happy Father’s Day to all the dads and soon-to-be dads out there — if you want to take the day off from sharing wisdom with your kids, you can direct them to this collection of advice nuggets from Free Press fathers instead.

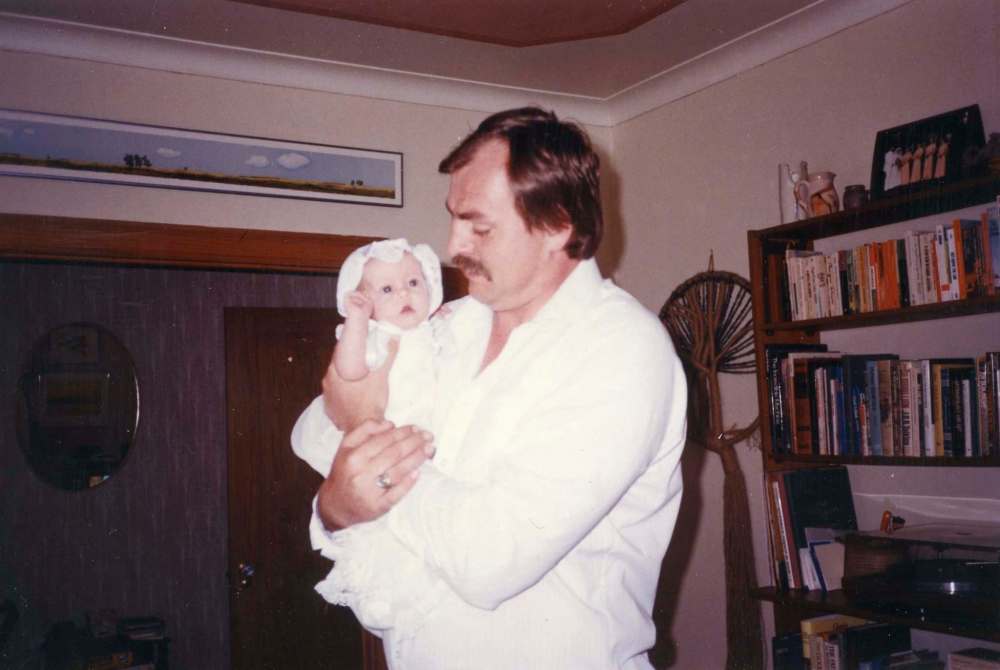

Bryen Lebar

Dad to multimedia producer Erin Lebar

For as long as I can remember, my dad has been considered by many as a guy who knows a lot about a lot. He is the ideal trivia team member and is always ready to drop a knowledge-bomb on any unsuspecting person who may ask him a seemingly innocent question (Though if my toilet ever broke, I’d definitely be calling my mom — he’s not much of a handyman).

A lot of the advice he has thrown my way has been financial. Classic Bryen lines include: “A problem you can solve with $500 isn’t a real problem,” (which he picked up from his own father) and, “Don’t sweat the small stuff.”

But the one that has stuck with me is, “You can always make more money” — meaning, don’t let the cost of something stop you from having incredible life experiences.

Now, he’s not talking about renting a jet and flying to the Caribbean, but, for example, when I was fretting about the high tuition costs of graduate school in New York City, he talked me off the ledge and helped me figure out a solution so I could afford to go after working so hard to get accepted. When I travel and am considering eating bread and cheese for dinner for the fifth night in a row to save money, it’s his voice in my head that says, “Go for a nice dinner in this beautiful new city.”

I have never once regretted listening to that voice.

It’s advice that I’ve passed on to my friends who have similar internal conflicts (being endlessly responsible versus enjoying your life) — You can always bust your butt to make more money, but you won’t always have the opportunity to relive those experiences you’d be passing up.

Jacques Samyn

Dad to editor Paul Samyn

Words were not my father’s strength.

His strength was the ability to withstand all that winter would throw at him as he stood on a snowbank along Ness Avenue watching me play hockey on an outdoor rink at the old Silver Heights Community Club.

As a father, I sometimes worry I haven’t had to show that same strength to my three hockey-playing children as those outdoor games of yesterday are now played while parents sit in the heated stands of today’s indoor rinks.

But then I remember Dad was there long after the snowbanks had melted away, much like my NHL dreams. While most parents became content to hear how the game had gone, my father was still there watching me play.

When St. Ignatius talked about love, he focused on how it “ought to show itself in deeds more than in words.”

My father’s deeds became the words I’ve tried to live by as I parent my children, being there to teach them to skate, to coach from the bench and to cheer in the stands. My hope is that the lessons of fatherly love I saw time and time again in so many hockey rinks as a child will be ones that I have been able to pass down to my kids and his grandchildren.

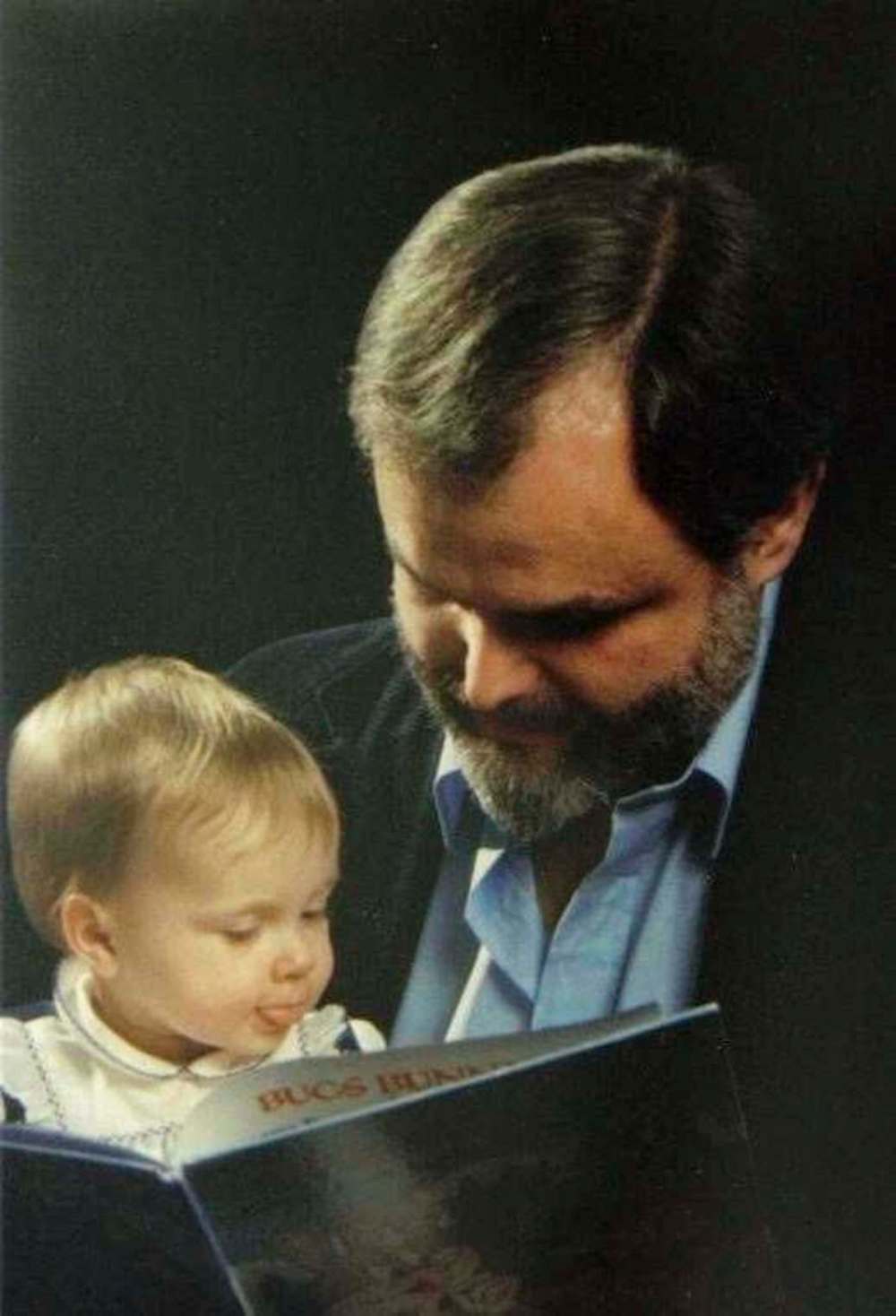

Dave Martin

Dad to reporter-at-large Melissa Martin

“The secret to life,” my dad would always say, “is to figure out what you love to do, then find a way to get paid.”

At night, guarded by stuffed animals, I set my young mind to work on this puzzle. The way most grown-ups spoke about work made it sound like an obligation, a chore. Is it possible, I wondered, that it could be something more?

Of course, I still wasn’t sure that my dad actually worked. I knew he had a job, which was called “a professor.” It came with an office — two, actually — at the University of Manitoba, where I drew rotund animals on dusty chalkboards.

But my dad never talked about “work” in the way I understood it. Some nights, he’d make oven fries and recount a particularly successful joke he’d told his students. He’d beam with pride when he spoke of their accomplishments.

If this was what it meant to have a job, then that’s what I wanted: to be that liberated, that joyful, that free.

Oh, it didn’t come easy. I was a bright child but a bad student. I chafed at the boundaries of my education, letting my mind obsess over topics in a depth beyond the curriculum: fantasy stories, languages, the Second World War.

But writing, that I was good at. When I was six years old, I wrote a novel about a pirate queen. In the foreword, just inside the notebook’s floral fabric cover, I penned a dedication: “To my dad, whom has always enjoyed my work.”

Soon, writing would become my only talent, my sole obsession. I dropped out of university to pursue it; I freelanced. I was flat broke. Every week, I borrowed my dad’s money and sobbed in his car, terrified I would never make it.

In those moments, my dad would guide the car aimlessly down long, dreary streets. He’d repeat his old advice to me, about the secret to happiness. I’d figured out the first part, he told me; it was just a matter of time for the second.

One day, I found a way to get paid. My dad’s advice helped me see it, but his commitment made me achieve it.

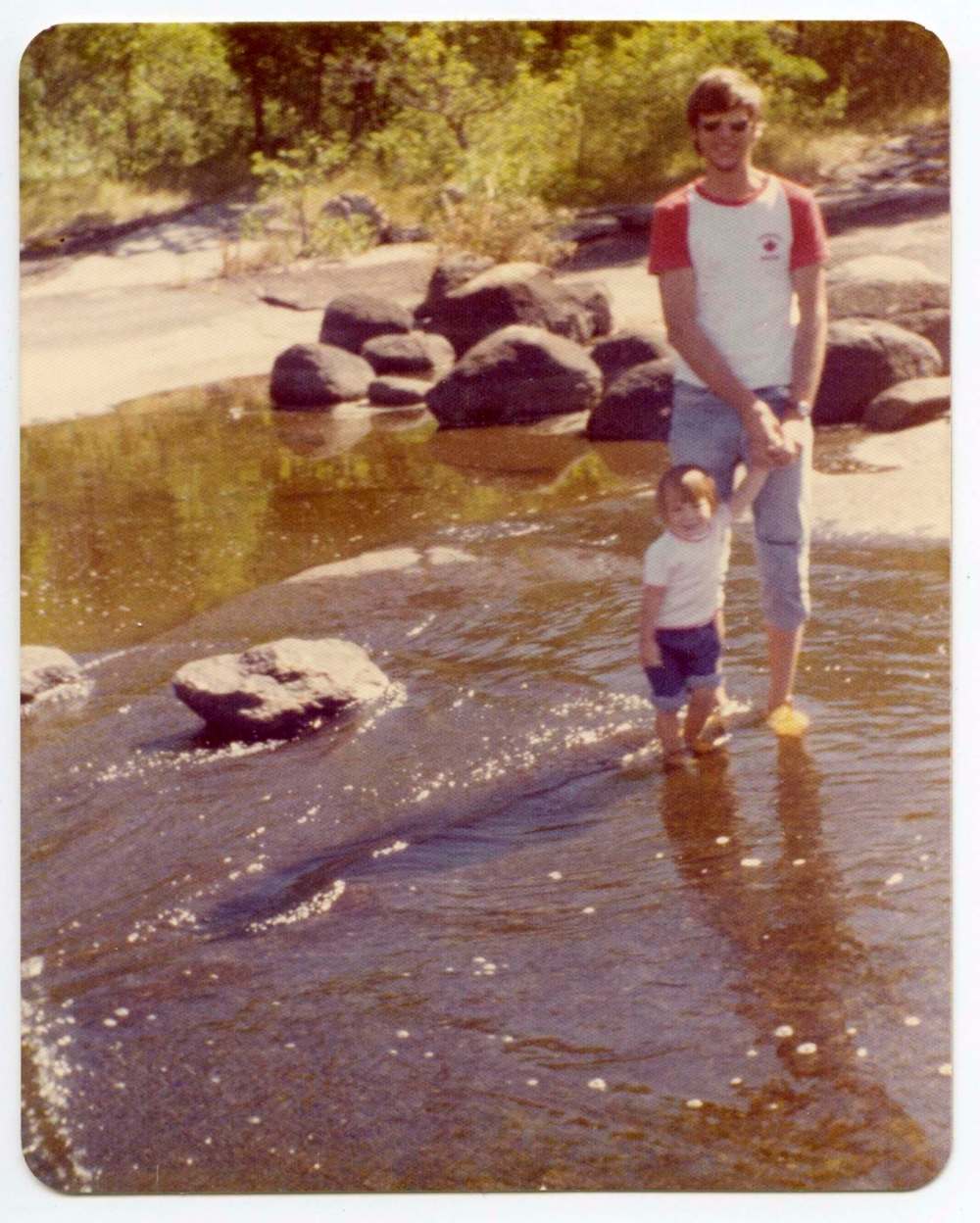

Gunther Aporius

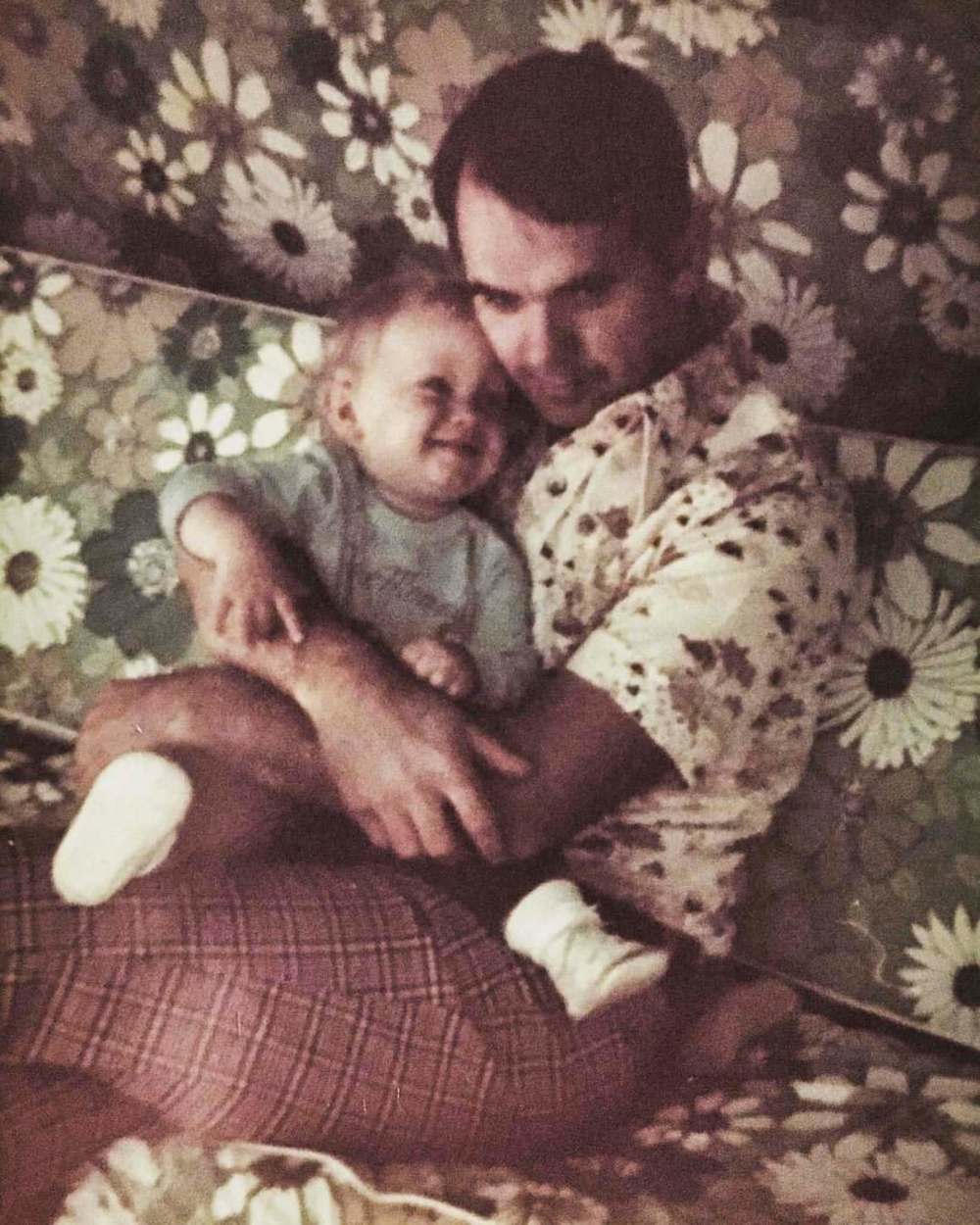

Dad to photo editor Mike Aporius

Growing up, my dad wasn’t much for small talk or sharing feelings. That came later.

I never learned much helping him in the garage, because I would never know what it was he was asking for. I’d just bring him an array of tools I thought made sense. I still can’t tell you the difference between a Phillips and a Robertson screwdriver.

The advice he did give was usually about money and was pretty simple: Save it. Don’t spend it on stupid things.

I never listened.

I started listening in my mid-20s when he developed prostate cancer. We spent the next 12 years before his death bonding like we should have from the beginning. He made me supper every Thursday… even during my stint as a vegan. Do you realize what a sacrifice that is for a trained chef from Europe? He accommodated me with some amazing dishes while we watched Survivor and drank his homemade beer.

Now I was getting to know my dad.

My mom recently dug up an old photo I had never seen before. It was the two of us, circa 1976, on an old vinyl-cushioned patio swing, me in his arms smiling up at him as he cradled me. It was a love I didn’t recognize growing up, but now, as an adult with three young children, I see it instantly.

So the advice from my dad wasn’t as concrete as “use this kind of wrench on this kind of thing.” It’s more of a learned lesson: Don’t just love your kids. Show them.

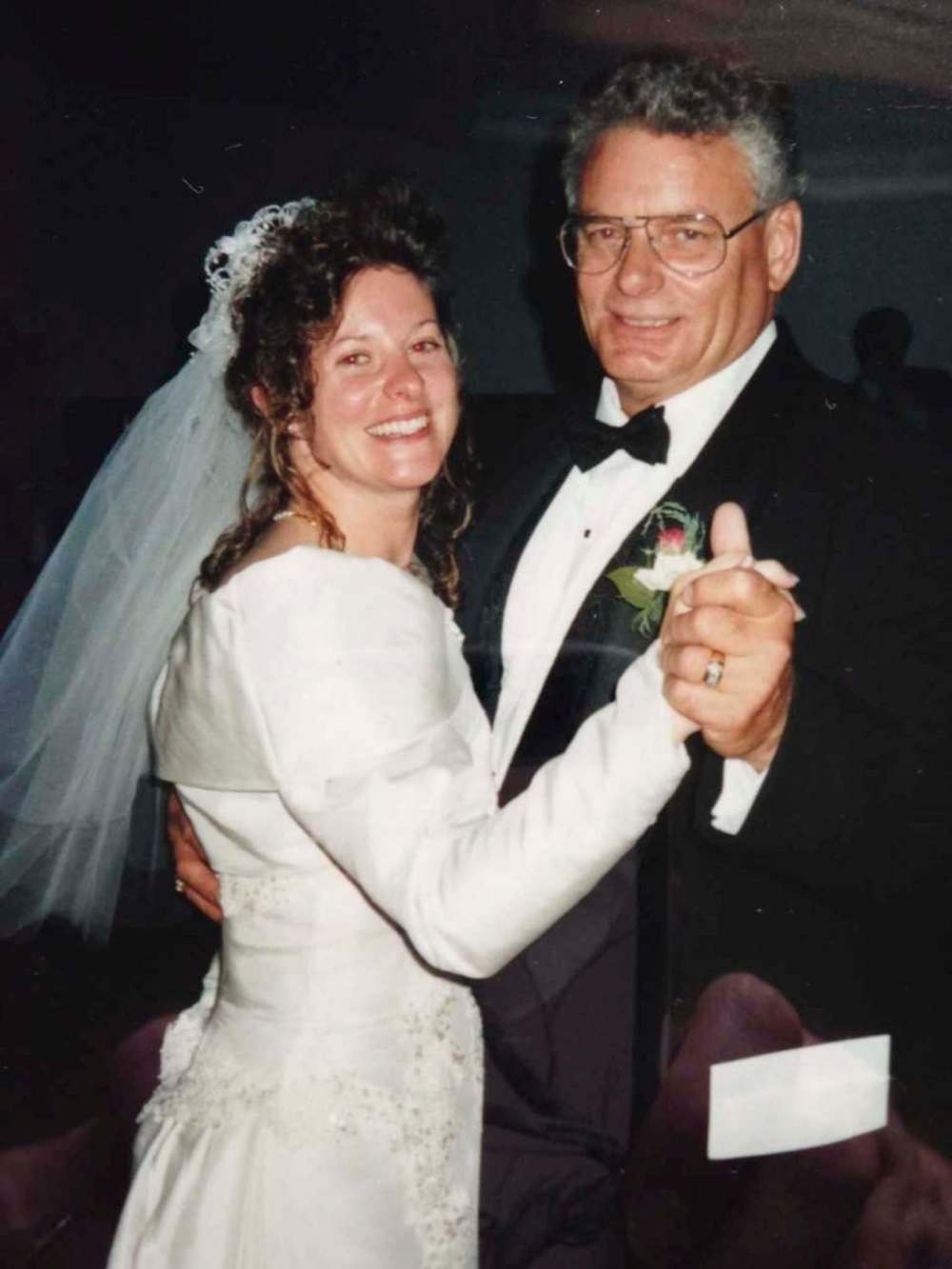

Bob Prest

Dad to reporter Ashley Prest

This is my first Father’s Day without my dad. He died on May 21. I’m going to want to talk to him or text him on Sunday but he won’t be there. The Winnipeg Blue Bombers have played two pre-season games and we need to talk about the offensive line or how much they’re paying the quarterbacks, like we always do every CFL season. The best fatherly advice my dad, a retired RCMP officer, ever gave me can be linked to sports but it can be applied to any situation in life. I have liberally applied it.

“The best offence is a good defence,” Dad said, many times in my life.

This means, to me, that bad things can be avoided by doing your best to stop them from happening in the first place. We can’t control everything in our lives, we all know that, but we can launch pre-emptive strikes. Dad’s advice is to take precautions, plan ahead, research and make the best decisions possible in advance.

This advice has kept me safe and continues to do so.

In 25 years as a sportswriter with the Winnipeg Free Press, I was often the last person to leave dark stadiums, empty arenas and gymnasiums. Everyone else was long gone and I was always on my own. On a nightly basis, I would leave random buildings alone, walk alone across shadowy parking lots and streets or drive alone late at night on highways. Nothing bad ever happened to me. Maybe I’m lucky or maybe God has watched out for me but I know Dad’s advice continues to keep me safe.

Where I park, lighting, available security, which routes I take, vehicle repair, checking in with someone before I leave and when I arrive — these are all defensive strategies that are offensive strikes against bad things happening.

Jimmy King

Dad to entertainment reporter Randall King

My father was a musician. I dare say in Winnipeg from the ‘60s through the ‘80s, Jimmy King was kind of a big deal. Maybe not to you. (Next month will mark the 30th anniversary of his death.) But ask your parents. Or grandparents. They might remember him as the musician who played their wedding or bar mitzvah. They may also remember him as a weekly night-life columnist for the Winnipeg Free Press.

Yes, that’s right. I’m a legacy.

Being a working musician is a challenging gig, especially if you have five children at home. When my dad was establishing his career as a musician and bandleader, he sold pianos at Eaton’s and Hammond Organs at Polo Park. It was in the ‘60s that the music career took off, and he could leave the day jobs behind him.

“Nine-to-five is jive,” he said.

Like most fathers of his generation, he eschewed father-child heart-to-hearts. He tended to teach by example. Hence, though he didn’t especially want his children to become musicians, my eldest brother Bob became one anyway. Next eldest, David, is also a musician and a playwright and actor. Middle brother Ian became a graphic artist and sister Gini went into accounting. I went into the endlessly glamorous world of daily newspapers.

I don’t recall him ever articulating the lesson, but I think we all learned it: Find something you like to do. Then find a way to get paid for it.

Do it even if it means you end up working odd hours, as when you’re filing a review after a theatre opening, or running to catch a midnight screening at the Toronto International Film Festival.

Nine-to-five, after all, is jive.

Henk Noordman

Dad to Uptown editor Leesa Dahl

My late father, a Dutch immigrant, had seven children before me, so by the time I came along in 1967 his words of wisdom were few and far between.

After child-rearing for nearly 20 years he had, I dare say, dispensed all the words of wisdom he might have amassed in his long life, and as a result, I received most of my counselling from a gregarious brood of older siblings who were more than happy to dole out unsolicited advice — good or bad — whenever the need arose. For instance, as I nervously prepared for Grade 7 back in the early ‘80s, my feisty, mop-haired brother, only two years older than me at the time, reminded me to “be nice to the ugly guys, ‘cause you never know if they’ll have any good-looking friends.” And as I grew into a young woman, my headstrong red-haired sister warned me that “all men are animals.”

In all honesty, I paid little or no heed to the lot of them. In true defiance, I repeatedly said no to men who asked me to dance, I rented when I should have bought and I may have thrown the first punch once or twice. But when my pop, a man of few words, told me to “stick with” a young, good-looking dock worker I met some 31 years ago, I did.

Ken Sawatzky

Dad to associate editor of digital news Wendy Sawatzky

My father, Ken Sawatzky, is an accomplished carpenter. For decades, he and my mother have worked together on everything from fences to furniture to major home facelifts. Their projects have outfitted the homes of their children (and now their grandchildren) our entire lives.

Aside from passing along rudimentary carpentry skills and providing great role models for co-operation and communication in a marriage — both of which I’ve tested to the max while assembling IKEA furniture with my husband — my parents’ workshop lessons also provided the best life advice I’ve ever received: “Measure twice, cut once.”

That’s great advice when you’re building something, of course: you’ll save yourself time, aggravation and money if you double-check you’ve got that length exactly right before you saw the end off that two-by-six. Or cut the light-switch hole in that sheet of drywall. Or take a sledgehammer to that plaster.

But as I’ve gotten older, I’ve realized it’s also smart advice to apply whenever you’re making a major — especially irrevocable — life decision. Thinking about quitting a job? Moving to a new house? Ending a relationship? Take the measure of what will result — and double-check your calculations — before you make the leap.

In carpentry and in life, it’s easier to check for a mistake than to fix one.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.