Dubious diplomas Manitoba high schools are 'graduating' students from a hybrid track combining grade-level curriculum with English-language learning; many don't know it won't get them into university or college

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 28/06/2019 (2359 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

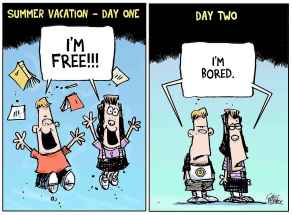

After the dinners and dances are done, some Manitoba high school grads will discover their diplomas take them down a dead end rather than a path to success.

A significant percentage of immigrant students are graduating with Grade-12-level “E-credits” that incorporate English-language learning with required subject matter, but aren’t full 40S-level credits required for admission to university or college.

“I knew those credits are virtually worth nothing,” said recent Gordon Bell High School grad and honour roll student Milka Tewolde, who arrived in Canada in May 2016 after fleeing Eritrea with her parents and three older brothers. Instead, Tewolde attended after-school programs to ensure she was on the right educational path.

But not all newcomer families in Manitoba know the limitations of an E-credit diploma.

“They’re wearing a gown and walking on stage believing they have a diploma but, come next (school) year, they’re being rejected (by university or college),” said Surafel Kuchem, who teaches at Gordon Bell and runs a Peaceful Village after-school program in St. James for the non-profit, non-governmental Manitoba School Improvement Program.

“They can’t take it anywhere.”

The E-credit system was set up to be a useful way for newcomer students to learn the language and the subject material. The problem, critics say, is when it’s used at the Grade 12 level to boost graduation rates and get students to leave school too soon. Without a solid education, the more likely they are to end up in low-paying jobs and, the longer they’re out of school, the harder it is to go back. And even if they want to return, it can be cost-prohibitive.

While some schools encourage students to stay as long as they can — until the age of 21 — and earn as many required S-credits as they can, other facilities urge students to leave when they turn 18 and have enough Grade 12 E-credits to receive an “E-diploma,” Kuchem said.

Tracking the implementation of E-credits is difficult. Not only do individual divisions have different approaches, in some case schools operating in the same division can adopt differing philosophies.

“It’s up to the school to decide,” said Paul Kambaja, a teacher who runs the English as an Additional Language (EAL) program at Grant Park High School. “It’s not right. This is a problem in our province. We have to do a better job to transition them to regular credits.

No school, no future

According to current projections through to 2024, just under one-third of all jobs will require a university education in Manitoba, while close to 30 per cent will require college or apprenticeship training. Another 30 per cent will require secondary graduation with some combination of occupation specific training, and the final 10 per cent will require on-the-job training.

According to current projections through to 2024, just under one-third of all jobs will require a university education in Manitoba, while close to 30 per cent will require college or apprenticeship training. Another 30 per cent will require secondary graduation with some combination of occupation specific training, and the final 10 per cent will require on-the-job training.

In 2018, school divisions across Manitoba reported approximately 150 newly arrived high-school age students had gaps of three years or more in their schooling. About three dozen had never been to school.

Manitoba “received the highest number of refugees in its history and the highest number of refugees per capita in Canada” in 2014, Manitoba Labour and Immigration reported, and that trend was maintained in 2016 with the federal government’s Syrian refugee program.

From Nov. 4, 2015 to April 30, 2019, Manitoba welcomed 1,490 Syrian refugees, more than half of whom were children (870).

Sources: Manitoba School Boards Association – 2020 Vision, Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, Manitoba Education and Training

“Graduating with E-credits, they don’t go anywhere. If and when they decide to attend adult-ed for the (needed) credits? “It takes them forever.”

And Manitoba needs an educated population. By 2024, 90 per cent of all jobs in the province will require more than just a Grade 12 diploma, a Manitoba School Boards Association study found.

At the same time, there has been a significant increase in new-Canadian enrolment here. Over a five-year period, Manitoba’s public schools have welcomed 23,000 new kindergarten-to-Grade 12 students who are learning English as an additional language. The youngest have time to learn the language and obtain the required curriculum to move forward after graduation. That’s not the case for the students who arrive in their mid- to late-teens.

The Winnipeg School Division is reviewing and overhauling its E-credit policy. And Manitoba’s Education Reform Commission is being asked to audit and reform the E-credit system, particularly at the Grade 12 level.

“It results in misleading data on graduation rates and does not hold the education system fully accountable for student learning,” the Newcomer Education Coalition’s brief to the commission said.

The coalition is made up of organizations that work directly with newcomer youths and their families with the goal to create welcoming, inclusive and equitable schools where all students have the opportunity to flourish.

The system doesn’t monitor the outcomes for newcomer youths graduating with E-credit diplomas, said coalition chair Kathleen Vyrauen.

And there’s no official policy encouraging them to stay in school to soak up as much curriculum as they can for as long as they can, she said.

“There’s so many different barriers, experiences and things going on that you can’t have a one-size-fits-all model,” said Vyrauen.

Some of the students were refugees and are missing big chunks of the schooling that was available to them in their birth countries. Some need mental-health supports as a result of their experiences, as well, she said.

“They need to know that they can go to a guidance counsellor to ask questions– like finding out what credits they need to get to where they want to be.” – Daniel Swaka

“It’s about giving those youths opportunities to explore what works best for them and how they can gain success,” she said. “Maybe post-secondary isn’t for them; maybe it’s a vocational program.”

But if they aren’t provided with guidance and support, they can’t optimize their time in high school. If they leave with E-credits or drop out before the end of Grade 12, they may never revisit their education.

She’s heard of older students encouraged by school staff to attend adult-ed offered by the Winnipeg School Division even though they’re under the age of 21; some teachers and parents are uncomfortable having 15 year olds in the same classes as 20 year olds.

What they’re not told is that adult-ed students who don’t live in the Winnipeg School Division’s catchment area have to pay a $770 fee per course.

“Situations like that are disheartening,” said Vyrauen.

The Adult Education Centre has enrolled many newcomer students who’ve discovered their E-credit diplomas weren’t enough to move on to post-secondary career paths.

“It’s incumbent on schools to explain that clearly so they know of the benefits and limitations of a 40E,” said principal Aaron Benarroch, adding that obtaining an education is a priority for most newcomers, particularly for those who come from places where it’s not a possibility.

“It’s part of the immigrants’ culture,” he said. “It’s that whole aura of opportunity that still exists. That culture is still dominant. That wish is still dominant.”

Attending high school in Canada would have been like winning the lottery for Paul Paul, whose family in Haiti couldn’t afford to send him to school beyond Grade 8. When he arrived here in 2015 at age 26 he was far too old for high school but his top priority was getting an education. He graduated this week from the Adult Education Centre with full-value Grade 12 credits, including English, math and physics.

It wasn’t easy, he said, adding his three best friends quit school in order to work. But his parents in Haiti, his university-educated wife in Winnipeg and adult-ed staff encouraged him to stay in school.

The trilingual Paul — who speaks English, French and Spanish — is hoping to work at the Canada Border Services Agency and has applied for Canadian citizenship. He and his wife have a five-month-old daughter, and for her education, the sky’s the limit.

“I’m happy she was born in a good country,” he said.

The non-profit Manitoba School Improvement Program has run Peaceful Village after-school programs for newcomer youths at six Winnipeg schools since 2009. Executive director Daniel Swaka said he is hoping the Education Reform Commission will ensure that schools throughout the province provide newcomer youths with guidance.

“Students are not aware of what they could ask for or how to advocate for themselves,” he said.

In addition to tutoring and providing scholarships, the Peaceful Village is encouraging students to be their own advocates, he said.

“They need to know that they can go to a guidance counsellor to ask questions — like finding out what credits they need to get to where they want to be.”

Helping them succeed in high school so they can pursue post-secondary education and get a better job is, of course, something that benefits the students; it also is of tremendous value to society overall, said Kuchem, who runs the Peaceful Village program in St. James. Kuchem immigrated in 2005 at age 19 after both his parents died and an uncle in Canada sponsored him.

“There’s a lot of pull from the street, with money and all the stuff that would distract you,” he said, explaining that after-school supports and guidance can help students make better choices, and while encouragement from family is a big motivator, so too are role models.

Not too shy to try

Diyar Salih didn’t speak English when he arrived in Canada four years ago as a Yazidi refugee. On Thursday, he graduated from Grant Park High School fully qualified to apply for admission to the University of Manitoba.

“I want to get my degree in social work,” said the young man who is already serving unofficially as a social worker in the Yazidi community.

Diyar Salih didn’t speak English when he arrived in Canada four years ago as a Yazidi refugee. On Thursday, he graduated from Grant Park High School fully qualified to apply for admission to the University of Manitoba.

“I want to get my degree in social work,” said the young man who is already serving unofficially as a social worker in the Yazidi community.

Salih went from knowing only, “Hi, how are you?” and “sorry” to getting a part-time job at Hermano’s and his driver’s licence. He spent last summer working with newcomer youths at NEEDS Inc. downtown.

He attributes his success to one thing: “I never get shy.” He said he wasn’t afraid to try and fail or ask for help.

“None of us are perfect,” said Salih.

He’s received help from his school’s English as an Additional Language program run by Paul Kambaja, as well as dedicated volunteers and tutors with Operation Ezra — a coalition in Winnipeg that advocated for the persecuted Yazidi minority facing genocide in Iraq and sponsored them to come to Canada.

The young Yazidi man wowed his teachers at Grant Park, Kambaja said.

“He’s mature and he works very hard in class, knowing he has some challenges,” said the teacher who has advised and tutored Salih during and after school.

“He’s also looking after his family, and is the only driver.”

Salih used his earnings from work to buy a vehicle; not a sporty car for a single guy, but a van with lots of room for transporting members of his community.

“He has to do his school work, at the same time he’s part of the community taking members to appointments,” Kambaja said.

“He’s very kind. Every teacher at school likes him; he’s that kind of student,” Kambaja said, adding Grant Park does not issue E-diplomas.

Salih worked hard and benefited from extra help, said Kambaja who, for 11 years, has run Newcomer Youth Educational Support Services in the summer, helping refugee youths catch up on their schooling.

“It’s very important, since we’re having a lot of students from war-torn countries,” said Kambaja, explaining they have big gaps to fill in their education before they age out of high school at 21.

“They’re learning the language, they’re learning the content and they have only two or three years to graduate.”

The research shows after-school and summer programs are vital for their success but it’s an annual battle to get funding, he said.

“We struggle every year looking for space, looking for money,” said Kambaja. The funding often arrives on short notice and is limited so they often have to turn students away, he said.

“These are kids who need this program and they want to be there. They want to be with their friends and they want to learn. They want to go back to school in September.”

When they fall even further behind, they get discouraged, he said. “They don’t stay in school.”

— Carol Sanders

At a recent Peaceful Village celebration attended by hundreds of students, their families, teachers and supporters including Mayor Brian Bowman, the big screen in Gordon Bell’s gym flashed the names, photos and future plans of the program’s 106 Grade 12 grads.

“We announced they were accepted at the U of W or U of M or where they’re taking the next step,” said Kuchem, adding it shows younger students in the program where they could be “so they’re aware of the possibility.”

Among them was honour roll student Milka Tewolde, who’s headed to the University of Winnipeg in the fall.

“When I first came here it was kind of scary because it’s a new place and a new language,” she said. “The Peaceful Village was a really good place to get help if you’re a new person,” said the 19 year old, who’s now volunteering with the program.

“You see that you’re not the only new person who’s there. That makes it easier.”

She’s now focused on biochemistry, getting into medical school and becoming a dermatologist.

“How skin works is really fascinating to me,” said the super-achiever — a voracious reader who played varsity soccer and works part time at a movie theatre. Tewolde, who fled Eritrea with her parents and three older brothers, is making the most of the opportunities she has in Canada.

“We are here because our country doesn’t allow people to live freely,to learn whatever they want,” said the teen, who faced unpaid, interminable military service in Eritrea.

“We’d rather be in our home country, where we’re born; we’re here because we don’t have a choice. We’re very thankful for the opportunities we’ve gotten in this country.” Canada will be repaid, many times over, for investing in young newcomers, she said.

“They’re the future.”

carol.sanders@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Wednesday, July 3, 2019 10:32 AM CDT: Corrects reference to Kuchem's immigration status.