In the water

The strike, Shoal Lake and Indigenous dispossession

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$19 $0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for four weeks then billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Offer only available to new and qualified returning subscribers. Cancel any time.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 14/06/2019 (2026 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Shoal Lake water first flowed in Winnipeg mains on March 29, 1919. About six weeks later, the Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council called a general strike, and this popular revolt would last a remarkable six weeks. The Winnipeg General Strike and the arrival of Shoal Lake water in Winnipeg taps occurred at the same time, and in the same place, and are part of a larger story of Indigenous dispossession.

Winnipeg’s population grew dramatically in the first decades of the 20th century. A little more than 42,000 people were enumerated in the city in 1901, and within 10 years, there were more than 136,000. Growth and the shape of it stressed an already fragile civic infrastructure. The annual appearance of typhoid in late summer and early fall got worse, especially for the poor who were concentrated in the city’s North End. By 1912, it was widely believed that the city, which had depended first on river water and then on wells, needed a new supply of water.

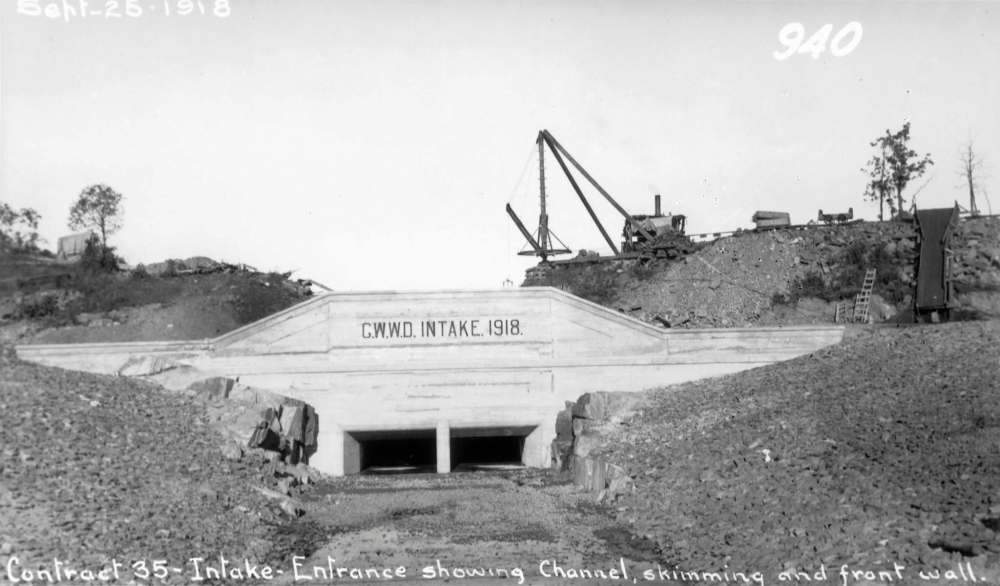

That new water supply would come from Shoal Lake, approximately 150 kilometres to the east at the border of Manitoba and Ontario. The Greater Winnipeg Water District (GWWD) began doing preliminary work on the Shoal Lake 40 reserve in 1914. Shoal Lake 40 community members negotiated with the GWWD’s contractor, and worked for them, clearing brush near the Falcon River diversion. Winnipeg’s chemist tested water samples and lived in the Presbyterian-run residential school, Cecilia Jeffrey, then located just east of Shoal Lake 40.

Building the aqueduct was expensive in both material and political terms. Winnipeg mayor Thomas Russ Deacon was elected on a “Shoal Lake water” ticket in 1912. To build and consolidate support for his plan, Deacon worked with people he would not have otherwise chosen to, including the organized labour movement. Deacon was a well-heeled civil engineer and businessman who lived in Crescentwood, extolled free enterprise and refused to recognize unions.

But when Deacon led a group of civic leaders on an “inspection tour” of Shoal Lake in September 1913, he included Edward McGrath, president of the Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council (and yes, early 20th-century English Canadians generally spelled “labor” without the u), and former member of Parliament A.W Puttee, a labour moderate and editor of the Voice, a labour paper. At a meeting following the trip, roughly 100 attendees heard McGrath and Puttee’s report, and voted to support the city’s plans. McGrath would later sit on the board of the GWWD’s “colonization scheme,” helping to oversee the granting of land along the Birch River in 40-acre homesteads to newcomers.

The aqueduct was built between 1914 and 1919, and a critical part of it involved Shoal Lake 40’s reserve lands. The archives of the Department of Indian Affairs in Ottawa document the piecemeal process by which the Canadian government scarified the interests of Shoal Lake 40 in the interests of Winnipeg.

First, Indian Affairs conducted a “surrender” process that ended with Shoal Lake 40 losing their rights to the gravel and sand on the reserve. Second, and to particularly enduring impact, Ottawa invoked Section 46 of the Indian Act, which allowed them to unilaterally and without any process take reserve lands if they were deemed necessary for public works, by which they invariably meant settler ones. By this act, Shoal Lake 40 lost about 3,500 acres of reserve land and lake bed, and had their reserve cut into three pieces. Ottawa set the price for this and it was, as mayor Thomas Waugh would later call it a “nominal” cost of $1,500. In 1919, Shoal Lake 40 would lose another part of reserve lands to Winnipeg, this time by the process of “surrender” by which so many First Nations lost reserve land in these years.

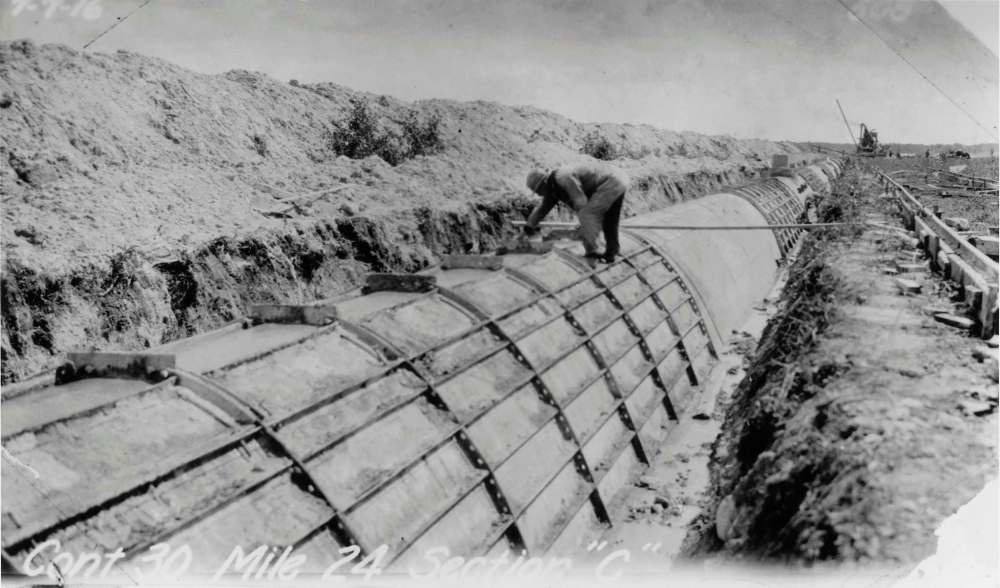

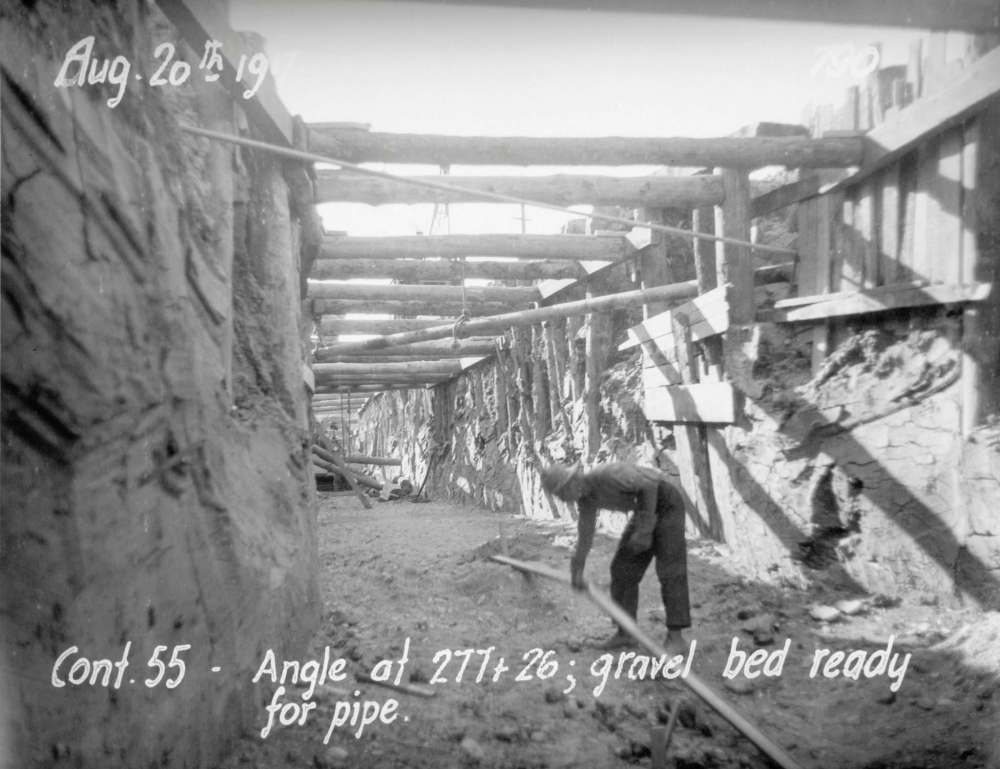

The construction of the aqueduct was a massive project, costed at $13 million, and coming in at about $17 million, equivalent to a little under $250 million in today’s currency. It involved a huge amout of human labour: as many as 2,500 people worked on the aqueduct at one time, much of it during the labour shortages of the First World War.

Most of the workers were young, male, and many of them recent immigrants. Policy mandated that the GWWD hire men who were residents in the municipalities that made up the water district — Winnipeg, Kildonan, Transcona, St Vital, Fort Garry, Charleswood, and Assiniboia. This added to the net of policies and practices that in the 1910s worked to keep Indigenous people outside of the mainstream labour market. Annishinaabeg men who had been an early part of the aqueduct’s labour force were squeezed out by the end.

By the time the strike was called in May 1919, the idea that the workers and citizens were non-Indigenous was so firmly entrenched that it occasioned no comment or explanation. You can search the pages of the Western Labor News for any mention of Indigenous people or lands and find none. When the strikers offered their powerful vision of a different Winnipeg and a different Canada, they were quarrelling with capitalism, and with the state, but accepting colonialism and what it meant for Indigenous people, including those who lost their land for the city’s water.

If you’ve been paying attention to the commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the Winnipeg General Strike over the past year — the museum exhibits, the monuments, the conferences, the walking tours, the musical — you are to be forgiven for thinking this had nothing to do with Indigenous history. The remarkable and enduring absence of Indigenous people from these histories reflects the events that worked to exclude them or, at the very least, make them invisible.

In the lead-up to the strike, labour newspapers published advertisements for excursion trips to Shoal Lake, promising a cheap holiday and a chance to see the work being done. There, they might have seen a reserve carved into three by land loss, and they might have seen a community cut out of whatever economic benefits might have been accrued from a major public works project. Or maybe not. The Winnipeg General Strike remains a powerful example of the power of collective action, organizing, and visions of a different kind of Canada. The way Indigenous people were excluded from this compelling and radical alternative deserves our attention and comment.

Adele Perry is a history professor at the University of Manitoba.