The nature of things Winnipeg photographer chronicles evolving landscape following Chernobyl nuclear disaster By: Kittie Wong Posted:

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 17/05/2019 (2402 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

On April 25, 1986, the world’s worst nuclear disaster took place at the No. 4 reactor at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Station located near the town of Prypiat, Ukraine, formerly part of the Soviet Union.

The explosion resulted from a failed late-night safety test meant to simulate a station blackout power failure. A combination of human error, lack of safety standards and design flaws in the nuclear plant were highlighted in two official reports on the disaster.

Shortly after, 135,000 people were evacuated from the area now referred to as the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. The zone extends 30 kilometres around the Chernobyl nuclear plant. Prypiat, now a ghost city, had a population of 45,000 at the time of the disaster. It was considered one of the best places to live in the former Soviet Union.

For Winnipeg photographer and painter David McMillan, the impetus for visiting the area stemmed from his interest in creating images that examined the tension between the natural world and the environment created by humans.

The motivation was a Harper’s Magazine article he read in 1994 written by American journalist Alan Weisman, author of the book The World Without Us.

Titled Journey through a doomed land: Exploring Chernobyl’s still-deadly ruins, Weisman described the condition of the exclusion zone eight years after the accident.

McMillan’s first visit to the zone was in October 1994. Since then, he has visited the area 21 more times, with his most recent trip occurring last November.

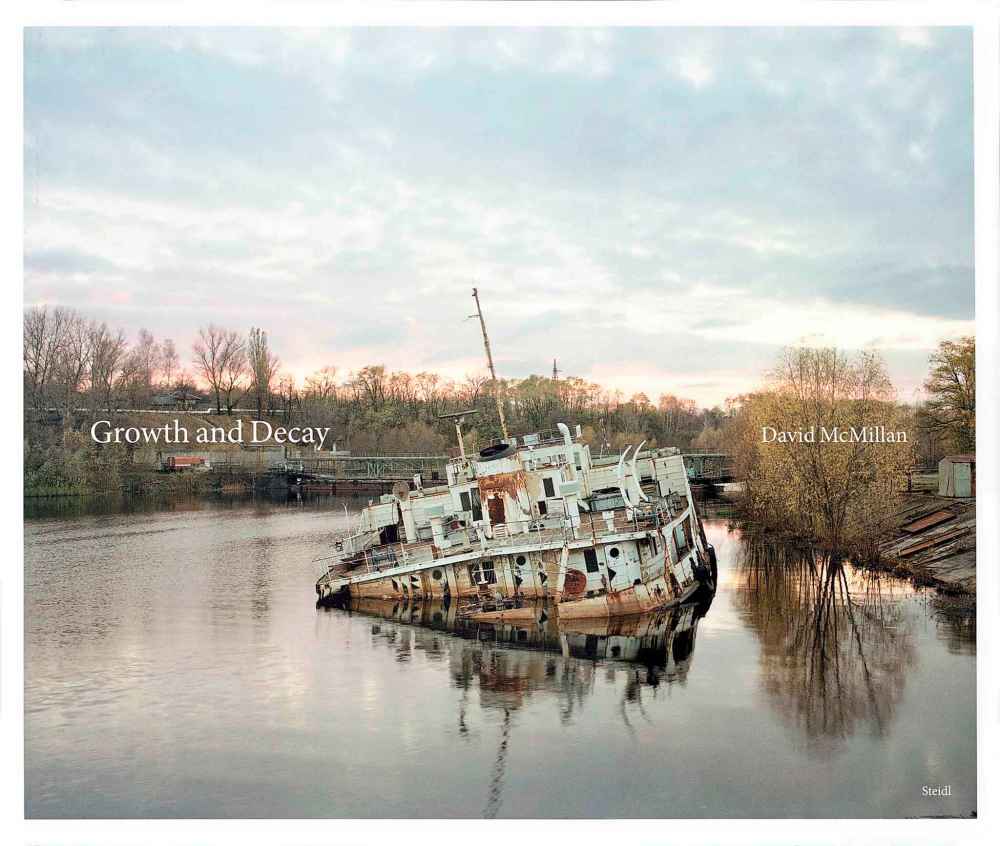

Now, the culmination of his commitment to observing the changes in the exclusion zone since the disaster has produced his newest photo book, Growth and Decay: Prypiat and the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. It includes an essay written by Claude Baillargeon, professor of art history at Oakland University.

McMillan sat down for an interview to discuss his book and his experiences in the exclusion zone. The interview has been edited for length.

When did you realize that recording and documenting the changes in the exclusion zone was going to be a lifetime commitment?

I was almost 50 (years old) when I started so it didn’t seem that it was going to be my life’s work, but in a way, it’ll be probably what defines my life’s work.

I didn’t go thinking of documentation at all. I maybe should try and make a distinction between journalism versus my own concept. It’s driven by a sensibility that doesn’t know what they’ll find.

You’re presented with circumstances and you see what you can do with it. Of course, it had a newsworthy dimension, which has made it seem and often it’s described as being a documentation.

Even in the essay, (Baillargeon) calls it “McMillan’s Chernobyl” because someone else would have done it very differently.

What was it about this place that has compelled you to go back time and time again?

Originally, I didn’t think I could go back. I didn’t know what I’d be allowed to see. I thought it might be limited. I didn’t know there’d be anything very interesting to see because even though this cataclysmic thing happened, it didn’t mean that it lent itself to interesting photographs.

The first time I went, I didn’t think I’d seen enough. I went back six months later and saw more of it and I still didn’t think I’d seen all that I wanted to.

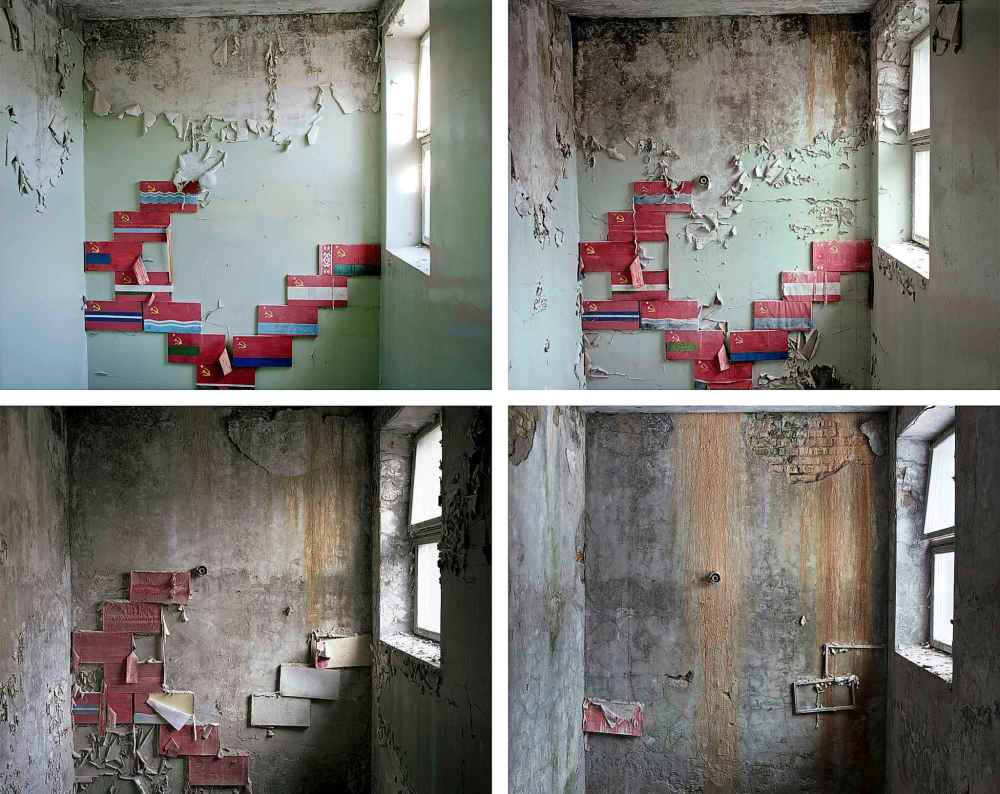

I went a third time and think eventually I realized I’d probably seen most of it, but interesting things were happening between the visits. Changes that are happening there through time.

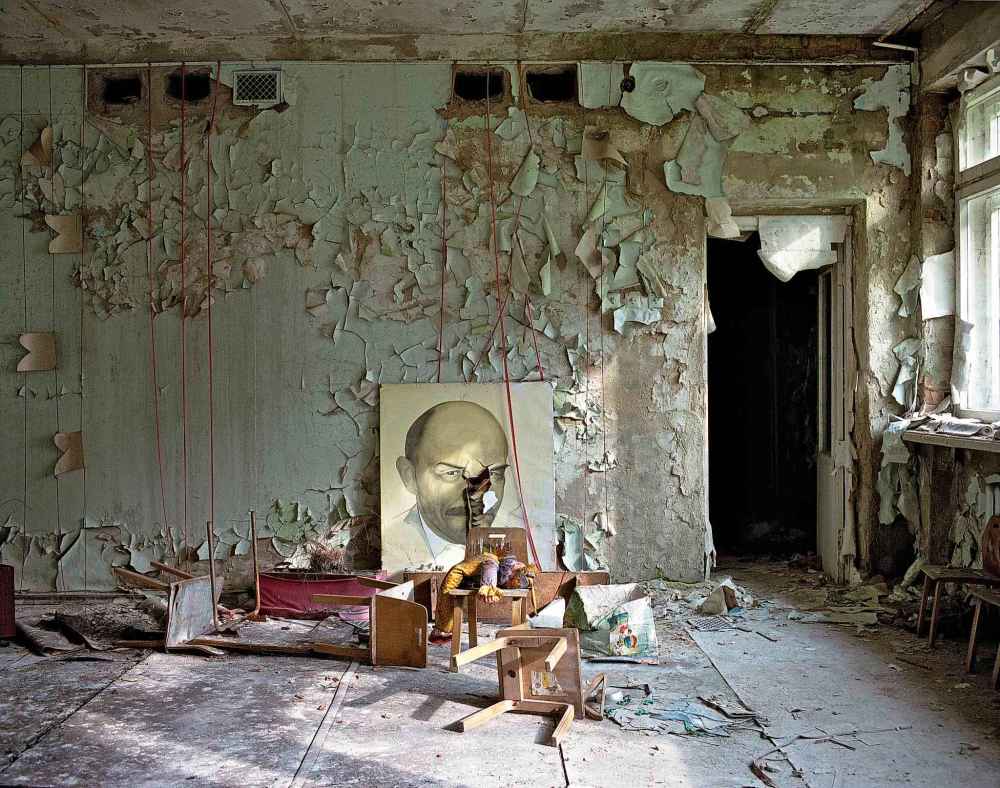

But also, I think I had an interest because it was a Soviet place. The accident happened in ’86 when Ukraine and Belarus were still part of the Soviet Union. There are all these artifacts that are scarcer today because of time and, I suppose, vandalism. It was the world’s worst nuclear disaster, which means part of the planet had been rendered unlivable because of bad design of the reactor and mistakes made by the technicians.

That resonated with me because I see this as we’re doing this to ourselves. But there was also the Soviet era, which was fascinating. And it seemed that this was becoming a distant memory. It pointed to how transient culture is, something that we think is going to last forever doesn’t, that was certainly in the case of the Soviet Union.

What kinds of logistical issues were there that you encountered in order to be physically there?

Initially, it was tricky to get there, to get in, to get admitted. I knew a colleague of mine was Ukrainian or of Ukrainian ancestry and knew people. He put me on to someone who knew of a woman who was working with CBC. She had gone with a crew to interview parents and children that might have been sick (from the Chernobyl accident). This woman knew of a Ukrainian filmmaker in Kyiv, who was one of the first on the scene to film her and he had a fax machine and spoke English.

So, I was given his number and after a number of correspondences, he said to come with US currency in various denominations. They picked me up at the airport, they found a place for me for the first night in Kyiv and then took me to the edge of the exclusion zone. They knew people that administered it and money changed hands and I was allowed in.

For the next five days, I could go anywhere I wanted. I had a car, a driver and an interpreter. I didn’t know what was there, so the man who was my interpreter/guide told me what I could see, which was anything.

I said, well, let’s try that and let’s go here and let’s go there. I saw most of what he thought was interesting in the area, then I got to the city of Prypiat, which is where I was really interested in based on what I read.

But I was there for a total of six or eight hours that first week, so I decided to go back and, subsequently, it was relatively easy. I had to get a visa, which was the case back then. You got permission from an administrator of the zone, then you sent your passport and some money to the Ukrainian Embassy and you got a visa — and that was it. Subsequently, because they had a fax machine in Chernobyl, I could communicate directly with the people there.

So there weren’t any areas that were restricted?

There were areas where I was told you might want to throw your shoes away after going in there. There was one place where they were burying the vehicles used in the cleanup even eight years after. There are photos in the book of large machines being buried in a large pit. I had to wear a mask there. That was the only place where I had to wear something protective. But otherwise, they’d say maybe you could spend five minutes here.

In fact, some of the vehicles were often too contaminated to leave the exclusion zone. So, they kept them for people like me, to take around (in the zone).

One of them was a van. I was in front of the reactor in an area that was considered contaminated and it wouldn’t start. I had used up my few minutes taking some photographs but a military vehicle came by and either pushed or pulled this van until it got the motor running. And for the rest of the day, the driver never shut it off because he didn’t think he’d get it restarted. He left the engine running the whole time while I just walked around and try to find what might be interesting.

They didn’t have a dosimeter the first time I was there. None of the people had one to measure the radiation so I rented one for my second visit and the people that were taking me around got to check the areas and see for themselves where it was contaminated.

How did the idea of this book come about?

It seems for a lot of photographers, it’s a natural way to deal with a lot of photographs. I had so many and I thought about it. I even made mock-ups. The challenge was to get it published because it’s an expensive book to make. The real catalyst was when I was at a conference in Toronto and (Canadian photographer) Ed Burtynsky was there. He’s published a lot of books and he said I should do a book.

I had been in a few exhibitions, so he knew what I was doing. He said I should meet his publisher who happens to be Gerhard Steidl (of Steidl Books).

The next summer, which would have been about two years ago, he said his publisher was coming to visit him in Toronto and I should come and meet him and bring some prints. So, I did. I met Steidl, we went to dinner and that was it.

How many images do you think you have taken?

Well, that’s 22 times I was there, so I’d say 10,000 to 15,000. The last four or five visits were shot exclusively in digital.

How did you go about selecting the images that are in the book?

Some of the images are now 25 years old. I knew the ones that still seemed interesting to me. So, it wasn’t too hard. Even now, there’s some I think maybe I could have chosen this version instead of that version. Part of it was to ensure I had the best ones. Also, there was a lot of attention paid to sequencing, to do something that made sense. The first third of the book is outside of where Prypiat is, its villages and things like that. And then the final two thirds is all Prypiat and its growth and then decay.

Was there another set of eyes who looked at your edits?

Yes, (Baillargeon) who wrote the essay. He’d make suggestions, which was valuable because, well, you can imagine. He was very helpful, forthright and offered me advice.

What are some of your most striking memories from your visits to the area?

Wow, there are so many.

Well, one evening when I was first there, you had to stay outside of the exclusion zone. Lately, I can stay right in the town of Chernobyl, but back then there was a little prefabricated village for people that worked cleaning up and all that stuff. That’s where I stayed and once on the way back to this place, leaving the zone, we came upon a man hitchhiking who was in the exclusion zone gathering mushrooms. So, we gave him a ride because we had this van, but he was quite drunk and he was bouncing into me and the driver was playing a (badly dubbed) cassette tape of the Jackson Five. The fidelity was terrible. So, here I was in the exclusion zone and it was pitch black. There were no lights except the truck’s headlights with this guy that had been collecting mushrooms, who was drunk and we’re hearing the Jackson Five.

Another time, I was at dinner in Chernobyl with a guy that I was told was a former KGB agent. He thought he had some kind of psychic powers. He had you stand up and put up his hands to feel your aura and everyone before me sort of fell backwards as if they were fainting and I thought that’s what he expected. So, I did that at a certain point too. It was just very strange. He didn’t want to be photographed himself.

The guy who was my interpreter and guide took a picture of me being held by this guy. It’s stuff that was unrelated to actually photographing there. It was a different world.

But things like coming upon the tree in the hotel room was surprising, and it was very moving being in the kindergarten (school rooms), especially early on when it looked as if people had been there recently and everything was still there like school records. And medical records, bags of plasma and medicines in the hospital. It was still there and it was very unsettling, strange and sad. There were those kinds of memories, but mostly there are a lot of pleasurable memories with the people I’ve met.

What have you discovered regarding the way nature reclaims a space that had been so greatly affected by the presence of humans?

I didn’t expect nature reclaiming itself. Before I arrived there, I knew of the red forest and all the dead trees. There were still areas where the tree trunks were still standing. It almost looked like the aftermath of a fire. There were no charred trunks or anything.

For the most part, I didn’t expect nature to be able to bounce back the way it did when you know humans apparently can’t live there and won’t be able to, or at least in Prypiat for another hundred years or so.

It was heartening. It was encouraging to know nature seems able to tolerate the kind of human foolishness that we visit upon it. But at the same time, the things we make don’t last very long. The remnants of ancient cultures are still around but you know much of Winnipeg isn’t built like the pyramids or the Parthenon.

Growth and Decay: Prypiat and the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, published by Steidl Books, is now available at McNally Robinson Booksellers.

kittie.wong@freepress.mb.ca

Kittie Wong wears three different hats for the Winnipeg Free Press editorial department: page designer, picture editor and web editor.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.