Code: meth City's first responders in nightly battle to find traction on streets dusted with cheap, destructive drug; ER nurses head to work fearing psychosis-fuelled violence

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 18/12/2018 (2642 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Roaring down Corydon Avenue with siren blaring, precious seconds tick by as Jay Shaw waits for drivers in front of him to get out of the way.

It’s a Friday evening during rush hour and the assistant chief of the Winnipeg Fire Paramedic Service is heading to Main Street Project, downtown Winnipeg’s only “wet” shelter, which allows people who have consumed drugs or alcohol to access services and stay overnight.

He’s responding to a call about two people showing signs of medical distress, potentially meth psychosis.

Shaw uses four words to describe every meth-related call the WFPS gets.

“Consistently inconsistent,” he says. “Predictably unpredictable.”

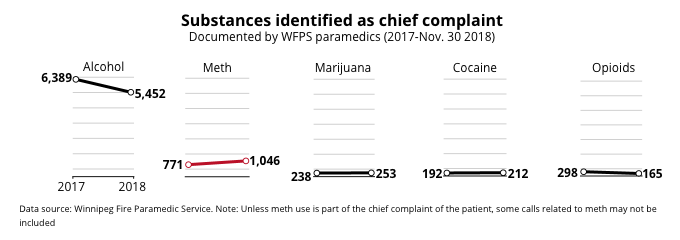

WFPS received 7,128 chief complaints about substances from January through November this year, compared with 7,888 in all of 2017.

The vast majority of complaints (5,452) were related to alcohol, which was the same as last year (6,389). The complaints catalogued are based on patients’ and paramedics’ descriptions of events.

Crystal methamphetamine continues its upward climb as runner-up. There were 771 incidents in which meth was mentioned last year. In the first 11 months of 2018, the number was up to 1,046 — about a 36 per cent jump.

But the data doesn’t matter now, not while Shaw is stuck in traffic. He’s one of about 1,400 members of the WFPS, about 250 of whom take to city streets every night trying to save lives.

When he finally arrives at the Martha Street facility, two paramedics are wheeling out a gurney with a body on it.

A young woman’s frame is covered by a ghostly bed sheet. Only the toes of her dark high-top sneakers peek out from the bottom.

She isn’t dead.

“She’s extremely embarrassed; that’s why she covered her face,” Shaw explains after briefly speaking with her.

The stigma associated with drug use can still howl inside a user’s brain, no matter how high or how far away they are.

It’s not immediately clear what she took, so she’ll be assessed further, as will another young man Shaw describes as "belligerent." The paramedics suspect he may have consumed meth and alcohol.

The two ambulances speed off towards Health Sciences Centre, Manitoba’s largest hospital.

•••

In August, meth’s devastating impact on the health-care system became crystal clear. A leaked security video from HSC, considered by many to be the province’s most secure health facility, underscored the dangers front-line hospital staff are facing.

Footage showed a nurse being repeatedly punched by a patient allegedly high on meth. Four security guards stormed around a hallway corner as the patient flailed his fists.

After seven swings and about 18 seconds, the guards managed to tackle the patient to the floor.

“I think it was great; I’m glad it was leaked,” an HSC nurse says three months later. “It’s triggering change, or at least some small change.”

The nurse, one of three who spoke to the Free Press under condition of anonymity, says violence in HSC’s emergency room has “skyrocketed over the past couple years," along with the number of meth users showing up at the city’s hospitals.

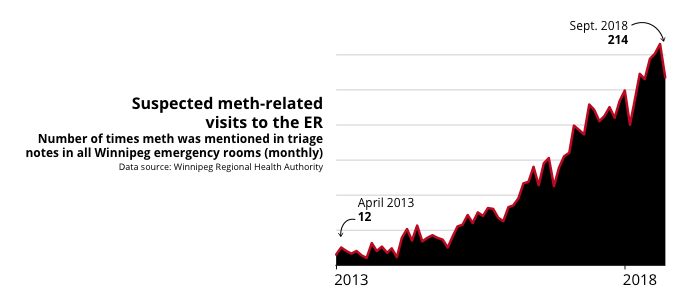

There were a dozen recorded meth-related visits to local emergency departments in April 2013, monthly counts compiled through triage notes by the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority show.

Five years later, the number in April ballooned to 218. It hit a peak of 252 visits in August, a staggering 2,000 per cent increase from April 2013.

“Before going to work and stuff, I sort of panic a little bit because you don’t know what’s going to happen today,” says the HSC nurse, who has been assaulted on the job.

"We’ve pulled weapons off of people… I pulled a bat with nails hammered into the edge of it off somebody… they gave it up willingly, but thank God."

Every shift is predictably unpredictable. Consistently inconsistent. But the nurse says one thing remains the same: “You’re just going and babysitting meth-heads all day."

HSC added more security measures in a pilot project rolled out this fall, including locking some adult patient units in the evenings and restricting visiting hours.

Ronan Segrave, interim chief operating officer, says the changes were made permanent early this month. And the hospital will soon expand the measures to other facilities focused on treating women and children.

In November, HSC began to provide staff and volunteers with personal alarms, which they can attach to keychains or lanyards. Seven thousand of the "screamers" have been doled out so far and another 2,000 are expected to arrive in January.

The alarms arrived after a staff member was pepper-sprayed when leaving after a shift, a nurse says, noting other staff have also been attacked.

Segrave says the move wasn’t spurred by a specific incident. He likens the devices to a "hand grenade," which staff are advised to throw away from themselves, using the loud noise to distract an assailant.

"Personal alarms can’t be used in isolation from other security measures, but they are an additional protection, if you like, for staff who do find themselves alone or walking through the campus in a dark area," he says.

After the August security video leaked, all HSC staff received a memo warning against speaking to media and notifying them that an internal investigation was underway.

One nurse doesn’t believe the WRHA would have made any security changes if the assault footage hadn’t leaked.

The nurse isn’t sure if they want to continue working in emergency.

"I wanted to help people for sure, for sure, but now it just seems so futile,” the nurse says.

“Meth is the problem. Like I said, I used to love my job… I was really good at it. And now I’m just like, I don’t even feel like I want to do it anymore because it’s just so dangerous."

A nurse who works next door at Children’s Hospital is also noticing changes in that ER.

“We have seen an increase in children presenting with meth use,” the nurse says. “The children arriving are often combative, requiring they be physically restrained as well as chemically restrained to keep them safe.”

It can take up to five or six security guards to keep the kids, other patients and staff safe, the nurse says, noting the kids have been as young as 12.

Often it’s the same patients they see over and over again, the same children brought in by emergency medical services, the same kids who can’t remember their own names or addresses.

“So many resources are used to find their caregivers and resources used to keep them safe,” the nurse says. “It is so sad to see them crying out and scared and having no idea what is happening. We cannot talk to them… as they are violent and screaming."

Segrave, however, says the nurse’s concerns are overblown.

“First thing I want to make absolutely clear is they are not reflective of the Children’s Hospital emergency department… they are a very small minority," he says.

"In relation to those incidents that are in Children’s Hospital (emergency department) that do involve any degree of violence, the most common cause is alcohol. It’s not crystal meth.

“We are not seeing significant numbers of adolescents approaching with crystal-meth addiction. Not to say we aren’t seeing any, but it’s very small numbers."

A nurse at St. Boniface Hospital laments having too few staff available to deal with a spike in violent or psychotic patients.

“It’s like pulling teeth trying to get enough staff in, not to mention everybody is working overtime,” the nurse says, repeating a notion that’s been regularly raised this year by the Manitoba Nurses Union.

Staff at the St. Boniface ER began seeing more frequent visits by meth users as early as 2014, the nurse says. They have also reportedly been assaulted by patients experiencing fits of psychoses.

"One of the docs I work with got punched in the face and he’s a super nice guy,” the nurse says. “I’ve seen a pregnant co-worker get kicked in the belly by someone who’s high on meth.”

“There’s no rational thought with some of these patients, so it’s scary…. When I’m going in a room to talk to them, I take my stethoscope off my neck, I take my name tag off my neck. I don’t want to be strangled to death. These are not normal thoughts for someone’s job.”

Katarina Lee, a clinical ethicist at St. B, says violence in the workplace is an ongoing concern and meth-related issues have sprouted as a major issue.

Last summer and again in November, the hospital hosted addictions-education sessions in response to staff requests. It also added a security guard to patrol the emergency room 24-7 and established a multidisciplinary working group in the fall. They meet regularly to discuss safety and how the hospital can best respond to people with substance addictions.

More staff are also brought into the ER on an as-needed basis, says Sara Gilchrist, the hospital’s manager of nursing initiatives.

"It’s an ongoing dialogue every day, but we do enhance the nursing and health-care aide support when those situations come forward," she says.

MNU president Darlene Jackson says increasing violence in hospital ERs extends past the Perimeter. Meth’s grip has also taken hold at facilities in Brandon and Portage la Prairie.

"This is a long-term problem," Jackson says. "It can’t be solved overnight. We do know that we need more (treatment) beds. The question is do we need (supervised) injection sites for harm reduction? I don’t know the answer to that."

•••

Back at Station 1 at Ellen Street and McDermot Avenue, the busiest fire-paramedic hall in the city, Shaw talks with WFPS medical director Dr. Rob Grierson and Deputy Chief Christian Schmidt about the merits of supervised consumption sites.

Last week, WRHA documents revealed skyrocketing levels of syphilis and hepatitis B and C in the city, tied to a spike in intravenous drug use. Having access to clean needles and a safe space to inject could help slow the growth of such diseases.

However, considering WFPS crews see an overwhelming number of alcohol-related calls, Grierson says a managed alcohol program may be a more pressing concern for Winnipeg. Ottawa, Calgary and Kenora already have effective models.

"If you were going to support one in our city, in my own personal opinion, I think a managed alcohol program would be (key) because of the numbers of people. I think definitely I would put my eggs in that basket," he says.

"But I think it would be hard to do one and not the other, to be honest with you. I think if there’s funding for one there should be funding for the other."

Shaw offers his two cents.

"When these individuals come into these (supervised consumption) sites, it’s an opportunity for counselling, for relationship-building," he says. "An ability for them to start the process that they actually want to go down.

"So you’ve got to separate the criminality and the stigma aspect of (doing drugs)."

The men also debate whether Winnipeg’s situation constitutes a meth "crisis." Ever practical, Grierson pulls out his phone and looks up the definition.

"A time of intense trouble or danger," he reads. "The synonyms they use are ‘disaster,’ ‘catastrophe’ or ‘calamity.’"

He ponders the results for a minute.

"Crisis brings in a fear factor that I don’t think is quite warranted at this point," he says.

"Certainly for individuals that are touched by the effects of the drug, their families, the people around them, (they) absolutely understand it is a crisis for them," Schmidt says.

"In terms of the effects it’s having on our department, it’s putting pressures on all of the public-safety departments — fire-paramedic, police. I wouldn’t necessarily describe it as a ‘crisis,’ but it is in terms of our ability to manage what we’re being asked to come and respond to."

All three agree the government responses to the meth situation have so far been inadequate.

"They have to collectively get their you-know-what together and say, ‘OK, we all have a responsibility here to kind of solve this problem together,’" Grierson says.

And four days later, Mayor Brian Bowman, Health Minister Cameron Friesen and Winnipeg Centre MP Robert-Falcon Ouellette make a joint announcement about illicit drugs in Manitoba and establish a tri-level government task force to study and address the issues surrounding meth.

It’s the first time representatives from all three levels of government publicly discuss the province’s meth problems in the same room, years after the so-called "crisis" began.

The politicians say they were having discussions behind the scenes for months. And some measures — the establishment of Rapid Access to Addictions Medicine clinics, implementing flexible-length treatment beds and providing anti-psychotic drug Olanzapine to paramedics — are already being co-ordinated by different levels of government. Now, they’re ready to collaborate.

Maybe the politicians couldn’t hear the WFPS sirens before. Seems like they are being heard clearly now.

jessica.botelho@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @_jessbu

History

Updated on Wednesday, December 19, 2018 7:11 AM CST: Corrects typo

Updated on Wednesday, December 19, 2018 12:57 PM CST: fixes typo in cutline