An everyday horror story Brandon trailer park on site of unmarked residential school burial ground adds further indignity

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 24/08/2018 (2755 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It is a horror story. Or a tragedy. But, all the while, true.

An op-ed was published online Friday in the Globe and Mail, authored by researchers Lorena Sekwan Fontaine and Andrew Stobo Sniderman, who have visited the hidden Assiniboine River Burial Ground, where more than 50 students who attended the Brandon residential school are buried.

Building upon research published in 2015 by University of Manitoba graduate student Katherine Nichols, Fontaine and Sniderman travelled to the site last weekend.

What they found is brutal.

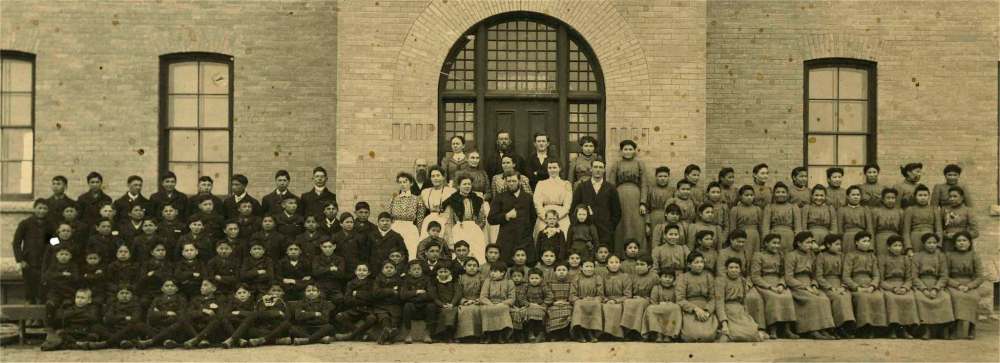

Starting in 1895, hundreds of children from 12 First Nations communities throughout Manitoba were removed from their homes to attend the Brandon residential school, run first by the Methodist Church and later the United Church. As the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s final report – issued in 2015, available free online – shows, the schools committed “cultural genocide.”

If you don’t know what happened in residential schools, read up. This is Canada’s history.

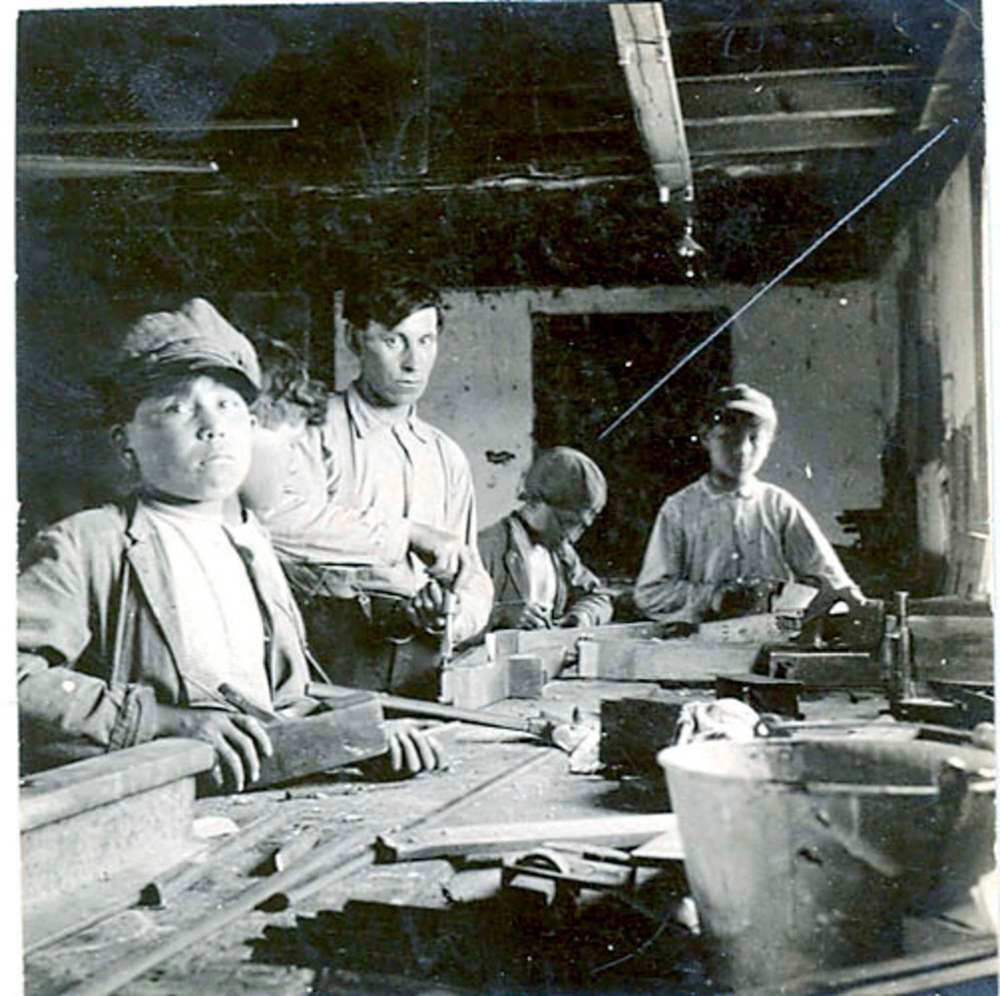

Any genocide has physical results. Death lived in the schools. Many attendees died due to neglect and violence. Malnutrition and disease were rampant. Abuse was a part of everyday life. This is why attendees are now often called “survivors.”

For the first 16 years of the Brandon residential school (to 1911), more than 50 students were recorded to have died.

Many of these students were from Sioux Valley Dakota Nation, west of Brandon, whose families still seek their whereabouts today. As the TRC report documents, school officials often did not mark graves nor keep strong historical records where and who was buried. A national search to recognize these locations is one of the TRC’s calls to action.

Regardless, children who died at the Brandon school were buried down the hill from it, near the riverbanks in the Assiniboine River Burial Ground.

Burials stopped there when the City of Brandon purchased the land and made it a public park. As Fontaine and Sniderman write: “The city bulldozed the area and removed the headstones. A massive circular pool was built. No doubt headstones would have dampened family picnics.”

For decades, a survivor of the Brandon school named Alfred Kirkness lobbied government and organizations in Brandon to have the site memorialized. In a 1964 letter to the Ministry of Indian Affairs, he reported “people stampeded over the graves,” and asked for the bodies of his classmates be exhumed or the site be protected.

In 1967, Kirkness found partners in the Rotary Club and Girl Guides, who installed a fence at the site and a large memorial stone with a plaque that read “Indian Children Burial Ground.”

There were no names on the cairn. “The dead we denied the dignity of names,” Fontaine and Sniderman wrote.

Even without names, though, the site had an impact.

I spent the late 1980s growing up in Brandon, on the North Hill, where I attended Kirkcaldy Heights Junior High School. Some of my most formative years were here, while my mother attended Brandon University.

My weekends were spent in nearby Curran Park, where I swam in the pool, played on swings, and skipped rocks on the Assiniboine River.

I remember walking by the cairn and seeing the plaque. I recall wondering why it was so far from the rubble of the Brandon residential school, which by then was a condemned building.

In those days, residential schools were barely spoken of. Certainly not in my schooling. Occasionally, I’d hear about them from family. Other than a few whispers, what happened in residential schools was virtually unknown to me.

I had survivors around me, all the time. I can only imagine what it was like for others.

Yet, right in front of me, was the truth of what happened in Brandon. Due to the tireless work of Alfred Kirkness and his allies, I knew a small piece of the story of residential schools.

I’ve often wondered about how, for many, this monument might have been their sole source of information.

It was certainly formative for me — so much so, I remembered it, almost 30 years later, when I spoke with Fontaine. (She and I share a beautiful daughter together.)

She told me about her and Sniderman’s research trip to the Brandon site last weekend.

This is where the story gets brutal.

In the early 2000s, the City of Brandon sold Curran Park to private interests. The land changed hands over the next few years and was finally purchased by Mark Kovatch. The site is now called Turtle Crossing Campground, and is primarily an RV park that hosts travellers vacationing through Brandon.

In recent years, the overflow from Assiniboine River, particularly in the spring, has flooded the site. Everyone remembers the impacts of the 2011 flood, but overflow was also deep in 2014.

In March, Kovatch submitted a zoning application to build a ring dike around the campground, at the cost of roughly $1.2 million. This resulted in new interest in the site — and the Assiniboine River Burial Ground.

The problem is years have gone by, and a lot of water has damaged the site. In June, Kovatch told the CBC he has seen evidence of human remains, but questioned precisely where the children are buried.

The memorial stone, which Kirkness used to mark the area, is now laying off to the side. The plaque is missing, with an empty indentation where it was once fastened. Whether moved purposely or water-shifted is unknown. If removed, this might be a contravention to the Manitoba Cemetery Act, which states “any person who willfully destroys, mutilates, defaces, injuries or removes any tomb, monument, gravestone or other structure” is breaking the law.

The bottom line is what’s there now: the site of the Assiniboine River Burial Ground is now an RV spot.

As of last weekend, an RV sits, parked, on top of where children are buried.

I stand corrected: this is a horror story.

The word “erase” is used a lot lately.

Federal Environment Minister Catherine McKenna used it when describing the recent removal of a Sir John A. Macdonald statue from the steps of city hall in Victoria. The Liberal MP said: “You can’t erase history.”

Conservative Leader Andrew Scheer – whose job is to disagree with McKenna – agreed, tweeting: “We should not allow political correctness to erase our history.”

Erasing is not what happened with the removal of a Macdonald statue. If anything, it meant the creation of a positive space. If a Canadian city wants to have a meaningful conversation about sharing space with First Nations, this conversation is impossible when a likeness of the architect of who removed them from that space is staring at them.

Maybe, one day, the statue can be replaced or contextualized. Just like Macdonald’s legacy, neither the City of Victoria nor the Songhees and Esquimalt nations are going anywhere.

Macdonald’s legacy is embedded in the fabric of Canada. As Sir Wilfrid Laurier said in 1891: “The place of Sir John Macdonald in this country was so large and so absorbing, that it is almost impossible to conceive that the political life of this country, the fate of this country, can continue without him.”

The country not only continued due to Macdonald, but was built on a foundation he built. A significant part of this is the residential school system, which resulted in the removal of children into assimilative institutions and legacies of trauma and violence seen in Indigenous communities today.

A primary outcome of residential schools has been, and is, genocide. Death.

Sir John A. Macdonald will never be erased, he is the eraser.

The evidence of his shadow lives in Brandon.

There’s an RV parked where children lay.

A genocide has happened and the evidence has been covered up.

If we let it continue, it’s not just a horror story. It’s one we’re also participating in.

niigaan.sinclair@freepress.mb.ca

Niigaan Sinclair is Anishinaabe and is a columnist at the Winnipeg Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Monday, August 27, 2018 9:43 AM CDT: Minor correction