A price on his life Kyle Unger, one of former prosecutor George Dangerfield's wrongly convicted 'killers,' spent 14 years behind bars for a grisly 1990 slaying; he's fighting for compensation the province says it doesn't owe him

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 08/06/2018 (2746 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

ROSEISLE, Man. — It’s a small meadow, really not much more, with tall green grass and trees at its edge. Somewhere behind the trees a small creek runs. It’s at the bottom of a hill where downhill skiers ended their runs during winters almost three decades ago.

It’s just two weeks shy of that weekend 28 years ago. It was the setting for a local music festival. Where Brigitte Grenier, a 16 year old from nearby Miami, was beaten, sexually assaulted, mutilated and strangled in what police said was one of the most horrifying slayings in Manitoba history.

It is also the place where Kyle Unger lost a huge chunk of his life.

And he is seeing it for the first time since he was last here in 1991, unaware that he was part of an elaborate police sting. The only other time was a year earlier, during the first — and last — Woodstick Music Festival weekend.

It’s a place where Unger doesn’t want to linger.

He reached out to the Free Press in March and travelled back to Manitoba this week from his home in British Columbia to speak with the newspaper about his nearly three-decades-long odyssey through the justice system and his $14.5-million lawsuit seeking compensation for his wrongful conviction from the province, federal government and the RCMP.

He’s willing to talk about Grenier’s death, his first-degree murder trial, his 14-plus years behind bars, his release after the federal government said his conviction was “likely a miscarriage of justice,” his acquittal a few months later and now, the lawsuit.

But not here.

“I don’t feel comfortable getting out here,” he says when the car slows near the meadow… the last time I was here was a year after it happened. Looking at it, there’s an incredible emotion of regret.

“This is one of the chains of where my life changed. I feel a little sickening, wishing I never went to that party. Anger that I went to it. We got there when the sun was almost completely down. We were only there for a short time.

“I wish I’d left just a few more hours earlier,” he adds as the car pulls away.

Unger has aged but, for the most part, the 2018 version doesn’t look much different than the one splashed on front pages and TV newscasts in 1990. He still has long hair parted in the middle. He still has a moustache and beard. He still favours T-shirts and jeans.

•••

After 23 years of holding money-losing tractor pulls, the agricultural society in Roseisle, a tiny hamlet about 100 kilometres southwest of Winnipeg, broke with tradition, gambling on a weekend rock music festival in late June, 1990.

And it paid off; after the first day, organizers said Woodstick was a financial success.

But the next day, two cyclists found Grenier’s nude and battered body in the Roseisle Creek that runs through the Ski Birch facility and the surrounding area.

Almost immediately, RCMP officers arrested and charged two local teens, Unger, then 19, and Timothy Lawrence Houlahan, 17, with first-degree murder.

But later in the year — after a preliminary hearing, the Crown is forced to drop the charge against Unger because of the lack of evidence. There were no eyewitnesses, and people called to testify said Unger showed no signs he had been in a struggle and there didn’t appear to be any mud or dirt on him, even though Grenier was found in a muddy creek. Unger hadn’t made any incriminating statements to investigators, and police hadn’t found any physical evidence tying him to the slaying. A dental expert wasn’t able to link bite marks on Grenier’s body to Unger.

He walked out of court a free man. Houlahan, however, remained under charge.

It wasn’t long before the RCMP set up Operation Drifter, a “Mr. Big” undercover sting operation as they later became known; it was the first time the tactic was used in Manitoba and only the second in the country.

The details, of course, are different in each case, but the basic structure of a Mr. Big sting involves a large team of undercover officers who befriend the suspect, convince the suspect they are part of a large criminal organization that is interested in recruiting the suspect. At some point, it’s made clear to the suspect that the way to earn the group’s trust is with a confession to a crime.

Unger took the bait. He not only confessing to the slaying, but also offered graphic details about what happened. RCMP had hours of secretly recorded conversations between Unger and undercover cops.

Open-and-shut, it seemed.

The problem, however, was that Unger had heard many of the slaying’s shocking details during the four-day preliminary hearing. He was financially, psychologically and socially vulnerable. His confession contained several incorrect details and he also told the undercover officers if he joined their organization, he was not going to commit any violent acts.

The inconsistencies weren’t enough to prevent an eight-man, four-woman Court of Queen’s Bench jury from finding Unger and Houlahan guilty on Feb. 28, 1992 after 15 hours of deliberations.

•••

Unger was working at a hobby farm when he first had contact with some of the Operation Drifter undercover officers.

One of the farm’s owners advised him to turn down an invitation from the cops to go for drinks. He says he shouldn’t have gone with them. And years later, he can’t believe many of the things he told them.

“(In court) I just put my head down in shame,” he says. “I was disgusted with stuff I said.

“But I still thought I was going to be found not guilty. I certainly believed (the jury) would come back and say ‘innocent’… (Jurors) took so long, I thought they are looking at it seriously.

“I knew they would convict (Houlahan) because they had all kinds of forensic evidence on him. They had more than they needed on him.”

He says he was stunned by the verdict.

“When the jury foreman said ‘guilty,’ all you feel instantly is a long, hot flash through your body. And then I thought, ‘how do I tell my parents this?'”

•••

The Supreme Court has warned judges across the county that while police can use Mr. Big operations to obtain confessions, the process has to meet a high standard in order to be admitted as evidence. Trial judges have to determine whether there’s any chance of misconduct during the investigation. If the evidence passes that test, judges have been instructed to determine whether the prosecution can successfully argue that the confession is more reliable than prejudicial to the accused.

Unger, unexpectedly, says there’s a place for the kind of operation that stung him.

“There was one where the person showed police where the body was,” he says. “How do you falsely confess to that? But if you don’t get valid evidence that could be corroborated, don’t enter it (in court).”

•••

Unger says he never had the chance to ask Houlahan why he pointed the finger at him. The rare times they were together, he followed his lawyers’ advice to not speak with his co-accused.

Inmates in remand believed he was innocent and made sure at least once that Houlahan knew that, sending a message delivered with their fists, resulting in a black eye.

“I know in my mind Houlahan is the main player of this,” Unger says. “In my mind, I believe there could have been two (killers), another with Houlahan, but not me.”

Unger’s current lawyers also note in documents filed in his lawsuit, that his trial lawyers were never told that the RCMP officer who conducted Houlahan’s polygraph test, reported that at one point Houlahan asked, ‘What if it’s not Unger?’

•••

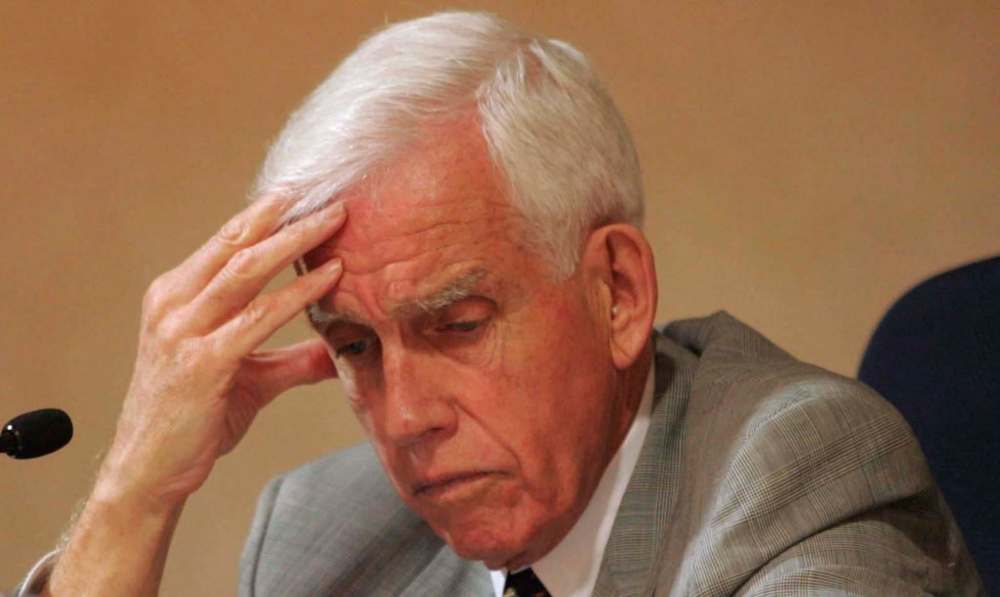

Former Manitoba Crown attorney George Dangerfield, who led the prosecution against Unger, “is the author of all of this,” Unger says.

Dangerfield, retired and living in B.C. now, was the renowned prosecutor who had a sterling record when it came to winning high-profile murder cases and putting killers behind bars. That is, until Unger’s case was overturned, along with the convictions of two other notorious “killers” — Thomas Sophonow and James Driskell — leading to troubling questions about Dangerfield’s conduct, along with that of investigators and others working in the Justice Department.

Frank Ostrowski, a fourth Dangerfield conquest, is about to join the others; he’s waiting for the Manitoba Court of Appeal to decide whether he will be formally acquitted or whether his 30-year-old murder charge should be stayed. The Crown and defence have agreed that his conviction for ordering a drug dealer’s death cannot stand.

“When you look at wrongful convictions and Dangerfield and you look at them all — wrongful convictions are not common,” Unger says. It happens once in a blue moon. But you don’t see any other prosecutors’ names behind it.

“I think he prosecutes cases not for justice, not for the victims, I think he acts the way he does in the courtroom, withholding evidence… just to get another feather in his hat. It’s a trophy for convictions. It’s not solving the case, but a trophy for that fellow.

“He’s a dangerous prosecutor.”

•••

After his conviction, Unger spent the next 14 1/2 years in various Western Canada prisons: Stony Mountain, Edmonton, Drumheller, Agassiz, B.C. His parents sold their house near Roseisle and moved close to each of the places where he was incarcerated.

He says the one and only positive experience behind bars was learning how to carve totem poles from a fellow inmate. His work is now sold in galleries in Vancouver and Victoria.

•••

Houlahan, who was awaiting a Supreme Court decision after the Crown appealed a Manitoba Court of Appeal decision to grant him a new trial, committed suicide in 1994.

Unger, who says the suicide tells him he was correct about Houlahan’s guilt, shed no tears.

“He’s where he deserves to be right now, six feet under,” he says. “What’s the expression? An eye for an eye.”

Unger was released on bail in 2005, and in 2009 then federal justice Minister Rob Nicholson issued a statement saying, “A miscarriage of justice likely occurred in Mr. Unger’s 1992 conviction” and ordered a new trial. A few months later, the Crown chose not to call any evidence and he was formally acquitted.

He celebrated with a Slurpee.

“I think it was Lime Rickey, he says with a chuckle. “It was November, freezing cold, and I walked down the road in freezing rain to get a Slurpee.

•••

When the RCMP arrested Unger was living with his parents in the house he and his father built a few kilometres north of Roseisle, from the foundation on up. They even dug the well outside. The shed — where he kept the horse his parents gave him on his 16th birthday — is still there.

Everything changed when the RCMP put the cuffs on him.

“This is the first part of what I want back,” Unger says. “This was the biggest loss of my life… this is where it all began, here. But with compensation, what does it give back? It doesn’t give you back what it took. It doesn’t change what you went through.”

Unger notes that at the time of his arrest he was working as a trucker with a local greenhouse, “a career that could have lasted decades.”

The lawsuit claims that because of the wrongful conviction “he was deprived of his youth, his education and a normal working life.”

Unger’s health has taken a beating through the years. He has had two frightening heart episodes and he is on medication to counter his high blood pressure. He broke his back while riding a dirt bike. He has jaw and nerve pain in his mouth, the lasting reminder of the emergency surgery he underwent after he was assaulted in prison.

A Manitoba Justice Department spokeswoman said “the province’s ability to comment is limited as this matter is still before the courts.”

In a statement of defence, filed in September 2014, the attorney general says Unger’s claim for “aggravated, punitive and exemplary damages are without foundation at law and are unsupported by the evidence in this case.”

The document also says the investigation into Grenier’s death was done in a “thorough, fair and careful manner” and no part of the prosecution was “undertaken maliciously… for an ulterior motive or with any animus towards the plaintiff or any other person.

“(The) charges were laid against the plaintiff based primarily on his own confessions to undercover police officers.”

Greg Rodin, Unger’s lawyer, says a trial date should be scheduled sometime later this year.

“These types of cases are notoriously slow,” Rodin says. “There’s the questioning of various parties… It takes a long time to go through thousands of documents.”

But Rodin says he is confident about the ultimate result of the civil suit because of what he sees were several intentional breaches of Unger’s charter rights. He said both the RCMP and the prosecutors failed to disclose several bits of information to Unger’s trial lawyers, including Houlahan’s question to the RCMP officer conducting the lie-detector test.

“How could you say that’s not relevant?” Rodin says.

“The constitutional rights of Kyle Unger to have a fair trial were breached… it was a clearly oppressive Mr. Big operation. There were a number of inducements for a vulnerable person.

“Can you imagine if Sheldon Pinx (Unger’s trial lawyer) knew at the time what Houlahan said — ‘What if it’s not Unger?’ It’s mind-boggling he was denied that.

“He’s so clearly innocent.”

Rodin, who was a partner in the Winnipeg law firm that represented Unger after his arrest and now practises in Calgary, has been providing his client with $1,000 every week since his October 2009 acquittal; he expects to recoup that money — an amount in the neighbourhood of $500,000 now — from the compensation he believes Unger will receive after prevailing in the lawsuit.

•••

Unger says it’s not just what he lost through the years he spent in prison that he has lost.

“I have these memories of what places looked like and I’ve had them for years,” he says. “But now I find, the more you go back, the more things have changed. It’s better not to go back. It doesn’t look the same way, so now your memory has changed.”

Likely a result of his years in jail cells, his life has been filled with instability since he walked out of that courtroom in 2009. He admits he has problems maintaining long-term relationships and is uncomfortable signing an apartment lease that would keep him in one place for a year.

“My friends call me a bit of a rolling stone,” he says. “I want to move when I want to. I think I need that.”

Unger looks wistful when he thinks of the life he could have had.

“The ripple effect in life of things you do… one small little decision and how it changes peoples’ lives,” he says.

“I don’t feel like I’m a victim. The RCMP were simply doing their job, but they were overzealous. I got into a few school fights in my day, so the RCMP didn’t like me. They had Houlahan, but they didn’t think only one (person) could have done it.

“They threw my name at him before he even said it and then he said, ‘Yes, Kyle was there.'”

Given the opportunity, what would 47-year-old Unger tell his 19-year-old self?

“If I could say something to him today, I would tell him to listen to his parents a little more and take their advice a lot more,” he says. “So many times Mom and Dad bailed me out of trouble. Helped me. Gave me a head start in things.

“I just kept wasting those opportunities. So I would tell that kid to stop pissing your life away and wasting opportunities.”

kevin.rollason@freepress.mb.ca

Kevin Rollason is one of the more versatile reporters at the Winnipeg Free Press. Whether it is covering city hall, the law courts, or general reporting, Rollason can be counted on to not only answer the 5 Ws — Who, What, When, Where and Why — but to do it in an interesting and accessible way for readers.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.