Flags on the play

Troubling questions are being raised about CFL's ground-breaking domestic violence policy as the league gives the green light to disgraced football star Johnny Manziel

By: Jeff Hamilton

Posted:

Last Modified: | Updates

By: Jeff Hamilton

Posted:

Last Modified: | Updates

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4 plus GST every four weeks. Offer only available to new and qualified returning subscribers. Cancel any time.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 02/02/2018 (2587 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

“I can look at our fans, I can look my daughters in the eye and they’ll know that I’ve done the best possible thing I can do,” CFL commissioner Randy Ambrosie said just hours before popping into a meeting. “I’ve made a thoughtful decision.”

In a phone interview from his Banff, Alta., hotel last month, Ambrosie spoke with unwavering confidence about his decision to allow disgraced NFL quarterback Johnny Manziel the opportunity to play in the CFL. Not only was he sure his office had made the right call, the commissioner seemed especially pleased with the steps taken to reach that final judgment.

“From this point going forward, we don’t do this alone. We don’t rely on the knowledge of the Canadian Football League to make these decisions,” he said. “We’re going to bring in experts, we’re going to consult with professionals, because at the end of the day, these are important decisions.”

In allowing Manziel — a former star college quarterback at Texas A&M who has since demonstrated a pattern of bad decision-making and has had multiple run-ins with the law, including allegations of domestic violence — to play in the CFL, Ambrosie settled what had been a years-long debate.

To some, Manziel is a man who deserves a second chance and therefore the CFL should give him one.

For others, to consider playing in the CFL a “second” chance — and not his third, fourth or fifth given Manziel’s documented history of destructive behaviour — it was hardly worth the argument.

Nonetheless, a decision had been made. Out of an abundance of caution (and in the event Manziel were to stumble again and a public relations nightmare ensued), the CFL was careful to reveal some of the factors that went into its decision.

In a Dec. 28, 2017, statement, the league said the decision was a result of “an ongoing assessment by an independent expert on the issue of violence against women, a review by legal counsel, and an in-person interview of Mr. Manziel conducted by the commissioner.”

Few other details were released, other than to suggest the vetting of Manziel was not and likely would never be truly “complete” as the 25-year-old native of Tyler, Texas, is still “required to meet a number of conditions set by the league.”

These conditions, and the process that led to them, remain confidential.

When asked why the public should take the CFL at its word — a league that has fumbled similar cases in the past — Ambrosie reiterated advice he received from experts.

“We just keep going back to what makes it different now is we’re going to bring these experts to the table and have them guide us to the right answer,” the commissioner said.

But a weeks-long investigation by the Free Press, conducted initially to better understand the CFL’s vetting process and to provide some clarity into how it had been applied to Manziel’s case, revealed inconsistencies and raised serious questions regarding the implementation of league policy both by the CFL and the Hamilton Tiger-Cats, the team that currently owns the rights to Manziel’s services and is trying to sign him to a contract.

At last update of the negotiations, Manziel was requesting the Tiger-Cats make him among the top-paid players in the CFL, despite not having played football for two years and with no experience in the three-down game.

● ● ●

To suggest the CFL will “no longer” be solely responsible for making the decisions when assessing high-risk players would be to ignore certain aspects of the league’s recent history. For the commissioner to further suggest the recent consultation of domestic violence experts in determining whether to allow a player to participate in the league is unique to his leadership is also misleading.

When Ray Rice, a star running back for the NFL’s Baltimore Ravens, was caught on video punching his then-fiancée — now wife — unconscious in a casino elevator in Atlantic City, N.J., it forever changed the way professional football organizations viewed gender-based violence. The September 2014 video — which shows Rice hitting his partner twice in the face, with the second blow causing her to fall senseless to the ground — sparked outrage from fans who demanded swift action.

Domestic violence has been a prevalent issue in professional football for decades before Rice stepped into that elevator. But the impact of his case — and the fact there was indefensible video evidence — triggered a ripple effect that went well beyond the NFL.

“There are many other people in society that do what he did, they just don’t happen to be on video,” said Clare Freeman, who spent 13 years as executive director at Hamilton Interval House, a community-based shelter that provides emergency and counselling services for women in the southern Ontario city.

“Unfortunately for him, though, his name is the one that sort of made everybody step up and actually say that they needed to do something.”

What happened in that Atlantic City elevator opened many eyes, including those inside the CFL head office.

Since it was impossible to rule out something like that happening in its own league, it was time for the CFL to start asking itself hard questions. How would it handle a similar situation? Who would it call for help? What is the appropriate punishment or treatment for those accused of domestic violence? What responsibilities does the CFL have in these kinds of situations?

wfpsummary:

Key elements of CFL Domestic Violence Policy• The policy applies to everyone who works for the CFL — not just players, but coaches, officials, executives and staff.

• Everyone in the CFL will receive mandatory training on violence against women and the issues surrounding it on an annual basis.

• The CFL will support, endorse and participate in efforts to increase awareness of violence against women and ways to prevent it throughout society, and in particular among Canadian youth.

• When any CFL workplace, including a CFL football club or one of its corporate offices, receives a report of violence against women involving a CFL employee, we will act.

• We will assess the situation and future risk to the women in question, and engage when necessary local experts who will make up violence against women response teams (VAWR teams). These VAWR teams will be made up of social workers and other professionals with extensive experience in dealing with violence against women.

:wfpsummary

• These VAWR teams will provide the best possible support and referrals to the women affected, ensure counselling is provided where it is deemed helpful to the men involved, and will strive to act always in the best interests of any children involved.

• We will always err on the side of safety, respect for the sanctity of human life, and every person’s inherent right to security from harm.

• We will not act as criminal investigators, fact finders, judges or juries: our focus is on providing access to experts who can intervene in a situation, assess the risk to the woman, mitigate any harm in the best way possible, seek behaviour change on the part of perpetrators and contribute to positive outcomes for individuals, families and communities.

• In cases where there are clear and documented cases of violence against women — determined by the police, the courts, or confirmed by the perpetrator — the CFL will impose sanctions.

• The CFL will also impose sanctions when there has been a clear violation of protection orders or other directives put in place by the courts or police, as such violations are clear indications of higher risks of violence.

• These sanctions will range from suspension for single or multiple games to a lifetime ban from the CFL, depending on the severity and number of incidences.

• In determining sanctions, the commissioner will consult a list of offences, including sexual assault, domestic violence, and violation of protection orders or other directives provided by the courts or police, as well as guidelines prepared in consultation with experts on violence against women.

• These sanctions will be subject to the provisions and processes of the league’s collective bargaining agreement with the CFL Players Association, and in the case of other employees, their employment agreements and employment law.

— Source: CFL website

The league set in motion a plan to implement its own strategy to combat gender-based violence — one that represented its unique needs and values. In August 2015, the CFL, in partnership with the Ending Violence Association of Canada (EVA Canada), announced a new domestic violence policy.

To experts in the field of gender-based violence, what the CFL had committed to was groundbreaking.

Unlike its football neighbour to the south, the CFL had “got it right” and the praise soon followed:

“Doing nothing will never be an option,” said then-CFL commissioner Jeffrey Orridge.

“Our players are truly leaders when it comes to generating awareness on this very important issue,” added Scott Flory, then-president of the CFL Players’ Association.

“Through this policy, the CFL is changing history,” proclaimed Tracy Porteous, a long-time, anti-violence advocate and co-founder of EVA Canada.

The policy was seen as groundbreaking not only for what it outlined — a three-pronged approach, according to EVA Canada’s website, consisting of policy development, training and delivery, and ongoing consultation on critical incidents — but also for the methodology the CFL planned to use when dealing with perpetrators of violence.

While the NFL reacted by installing a zero-tolerance policy aimed at punishing the offender, the CFL, with advice from its experts, vowed to take a much more “progressive” and rehabilitative approach. Instead of simply punishment, experts leading the policy for the CFL wanted to provide support for the accused and the victim, and to work actively with the men to see if they can change their behaviour.

“It’s actually offers much more of a wrap-around service for both the victim and also gives lots of opportunities for men to engage in changing their abusive behaviour,” Freeman said. “It’s not always about firing the person.”

In many ways, it was the start of a new beginning for the CFL.

“It used to be teams kept (players’ histories of domestic violence) under the rug and it’s taken our teams a while to learn better ways,” Matt Maychak, chief communications officer for the CFL, said in a telephone interview. “But now I’m confident that when something happens, our teams tend to call us right away.”

● ● ●

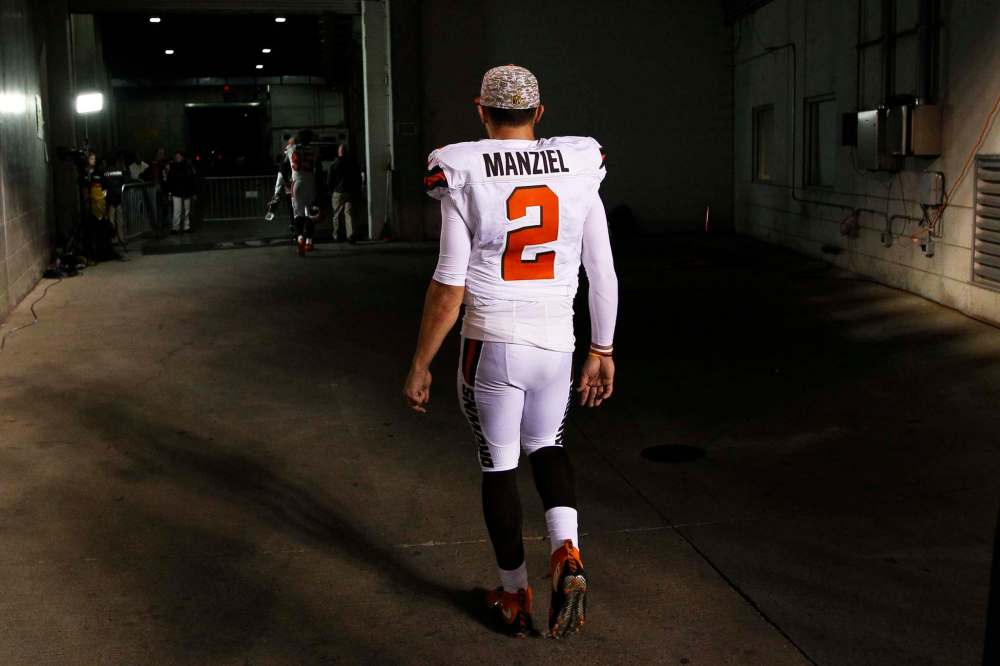

It’s hard to believe the CFL or anyone else could have envisioned a day Johnny Manziel — someone who was as popular for his antics off the field as he was for his play on it — would be looking for work in Canada.

Manziel took the football world by storm when he was named winner of the 2012 Heisman Trophy, becoming the first freshman to capture U.S. college football’s top prize.

At the age of 20, Manziel had led Texas A&M to a 10-2 record in its first season in the powerful SEC Conference, including a major upset victory over then-No. 1 Alabama.

He was an instant fan favourite and soon became known by the nickname “Johnny Football.” He captivated crowds with an accurate arm and a supernatural ability to escape pressure from defenders. Whenever he would throw or run for a touchdown, he would flash his signature “money sign” celebration to the delight of adoring fans.

But what appeared to be a road destined for greatness quickly took a detour. Manziel started to show signs of his immaturity in college, but it wasn’t until he reached the NFL that it was fully revealed.

Selected in the first round — 22nd overall — by the Cleveland Browns in the 2014 draft, it wasn’t long before Manziel found himself in trouble.

A constant love of partying, a lack of execution on the field and dedication off it, run-ins with the law and a trip to an alcohol and drug rehab centre were all reasons behind Manziel’s eventual downfall in the NFL. In two seasons with the Browns, he started just eight games, winning two.

Though he lost out on earning the entirety of his four-year, US$8.247-million deal with the Browns, he didn’t leave empty-handed, with more than US$4 million earned through a signing bonus. Manziel also signed lucrative sponsorship deals, including one with sports apparel maker Nike, though it’s unknown how much he was paid after they were terminated.

While the Browns started to grow tired of Manziel during his rookie season, it would be allegations of domestic abuse in his second season that led to his release from the team.

Barely a month into the 2015 campaign, after a day of drinking, Manziel was pulled over after police received “numerous calls” about a speeding vehicle. His girlfriend at the time, Colleen Crowley, told officers Manziel had hit her several times. She would later play down the incident to police, saying, “She didn’t want to make a big deal.” The two were allowed to leave together and no charges were filed.

Months later, there was a second incident involving Manziel and Crowley, this time following a night out in Dallas.

According to a sworn affidavit, in the early morning of Jan. 30, 2016, Crowley said Manziel threw her on the bed of their hotel room, where he physically restrained her and prevented her from leaving. When the two of them eventually left the hotel room together, Crowley claimed in the affidavit she was brought to Manziel’s car against her will after trying to flee.

It was at that point, she said, Manziel “grabbed me by my hair and threw me back into the car and got back in himself. He hit me with his open hand and on my left ear for jumping out of the car. I realized immediately that I could not hear out of that ear, and I still cannot today, two days later.”

On the way to her apartment, Crowley claimed Manziel threatened to kill both of them. When the fight continued at her apartment, Crowley, in fear for her safety, admitted to grabbing a knife and advancing toward Manziel, who eventually fled.

Dallas police launched a search for Manziel, due to fear he might harm himself. In multiple news reports, Manziel has publicly denied hitting Crowley. (Manziel’s camp did not respond to requests for comment for this story.)

Manziel was issued a court order, restricting him from contact or communication with Crowley for two years. In the ensuing months, as Manziel awaited a decision to whether or not his assault case was headed to trial, he was released by the Browns, picked up and dropped by another agent, and was involved in a car crash involving a rented Mercedes-Benz in Hollywood that caused an estimated US$90,000 in damage.

On April 28, 2016, Manziel was indicted on a misdemeanour charge for assault with bodily injury in the case involving Crowley. By December, he reached an agreement to have the charge dropped. As part of the agreement, Manziel had to attend an anger-management course and a domestic violence impact panel, among other conditions, over a 12-month span.

He also had to participate in the NFL’s substance-abuse program or attend a court-approved rehab facility (He still faces a four-game suspension should he ever return to the NFL).

Though it was never confirmed by the courts whether Manziel fulfilled his end of the deal, the charges were formally dropped Nov. 30, 2017.

Less than a month later, Ambrosie approved Manziel to play in the CFL.

● ● ●

When the CFL announced its new domestic violence policy in 2015, one of the strongest proponents was Len Rhodes. That’s because Rhodes, the president and chief executive officer of the Edmonton Eskimos, had grown up in a home haunted by domestic abuse.

In an article in the Edmonton Journal shortly after the policy was unveiled, Rhodes recalled childhood memories of his father verbally and physically abusing his mother.

“A lot of people stereotype us for being in football and everything that is macho about the game and sees us in one way,” he said in a recent phone interview. “But that day we basically came out and made it clear that domestic violence is not acceptable, that we were also going to do something about it.”

Rhodes took great pride in the CFL’s stance. Not only did it signify a shift from the past and how the league and its member teams used to handle the issue, whether involving players or other staff, he also hoped it would create more awareness when the topic inevitably came up in the future.

“There’s going to be certain cases where we’re not going to have a total alignment or a consensus in terms of how we would handle it,” Rhodes said. “A policy doesn’t make it perfect, but the fact that we have a policy and that we’re talking about domestic violence and challenging one another is positive.”

Asked how Manziel, given his troubled past and the risk he might pose to a CFL team, might have passed a risk assessment by league experts, Rhodes wasn’t about to play doctor.

He said the Eskimos aren’t interested in employing Manziel, so he knew little about the details of his past or current life outside of football.

However, with valuable resources now in place to help make well-informed decisions on these types of situations, Rhodes said he would never hesitate to reach out for guidance.

Just recently, he said, the Eskimos contacted Tracy Porteous, the CFL’s lead expert on gender-based violence, to help assess a potential player.

And, though he couldn’t comment directly on Manziel’s assessment, Rhodes can only assume others are taking the commitment seriously, too.

“I would only hope — and I’m going to put a big assumption here — is that the evaluation was made with some key experts that have assessed the situation and feel that there won’t be repeat behaviour.”

In Manziel’s case, the application of the process set out in the league’s policy is less clear.

While the CFL appears to have a relatively straightforward set of rules for people who commit violence against women while already employed by the league, there is some ambiguity for how to handle those who are “new” to the CFL but have a documented or alleged history of abuse.

The inconsistent perception of the policy and how it is to be applied appears to render its mandates more akin to “guidelines” or “recommendations.” Even still, it stands to reason the recommendations, including conducting fulsome player assessments, would be followed — or at least strongly encouraged — by a league looking to prevent damaging fallout.

“At one point, we had discussions about changing the policy to require (player) assessments,” Maychak said. “I think where it landed… is that it’s encouraged, not required.”

● ● ●

In essence, all that is required of the CFL’s policy, as Ambrosie alluded earlier, is a willingness to “do the right thing.” However, what is to be expected and encouraged of a member club — and the process followed — do not always line up and there appear to have been striking omissions when assessing Manziel.

While the CFL ultimately made the decision to allow Manziel into the league, it was the responsibility of the Hamilton Tiger-Cats to first do their own research, to provide the league office with enough evidence to warrant further assessment.

Hamilton has owned the negotiating rights to Manziel dating to when he was at Texas A&M, and has talked extensively over the past year of how valuable he is to the team.

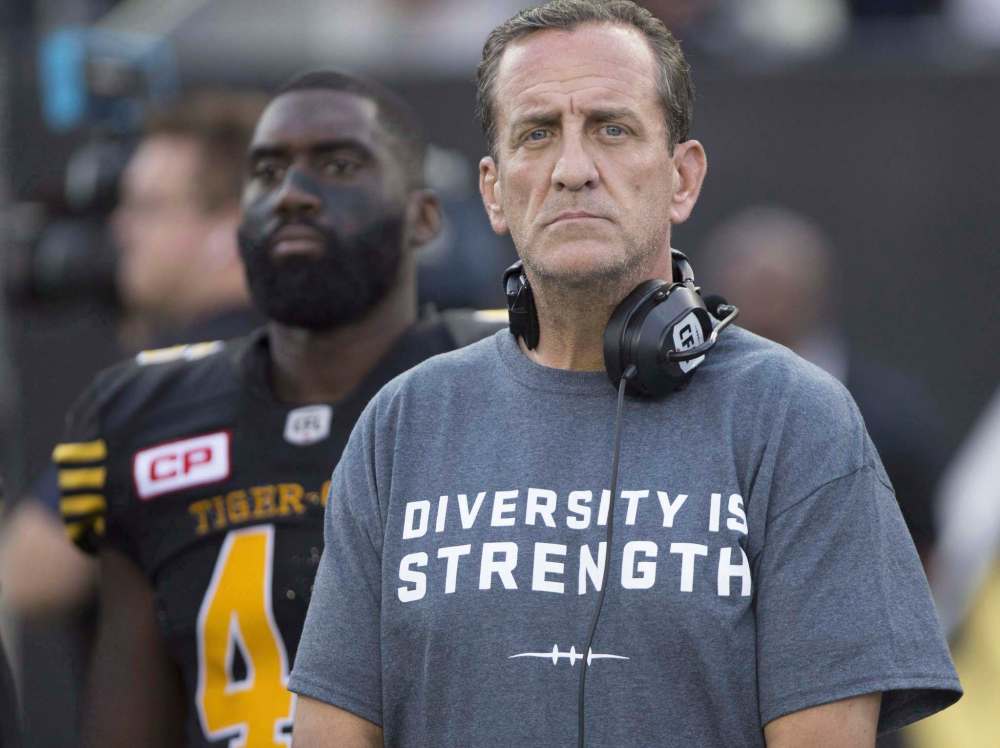

“We’ve had Johnny on our (negotiation) list for almost five years. We have a responsibility to evaluate every single player that’s on our (negotiation) list — we have to fully vet him, in every single area,” Kent Austin, Ticats vice-president of football operations, told reporters last August, shortly after he had removed himself as head coach following an 0-8 start to the season.

At the time, the Tiger-Cats had worked out Manziel, along with a number of other potential players.

“That is being done with all of our players and those factors are all considered. Don’t read too much into a workout to say that somehow we’re bypassing the evaluation in that particular area. We’re not.”

Following the decision by the league to allow Manziel to seek a CFL contract, the Tiger-Cats released a statement thanking Ambrosie for his work in assessing Manziel: “We appreciate the CFL office and commissioner Randy Ambrosie’s due diligence in this matter. We also recognize Johnny Manziel for thus far demonstrating the attributes necessary to continue his career in our great league.”

(According to reports, the Ticats have offered Manziel a contract, but for well below what his representatives are seeking.)

But what exactly did the Tiger-Cats do in aiding the commissioner on a decision that is usually vetted first at the team level?

The first step usually involves the team’s own research on the players, but then they are encouraged to seek out expert advice.

“We are not experts,” Edmonton’s Rhodes said. “I only know one part of the situation, but I’m not an expert in terms of evaluating and assessing people and that’s why I believe, coming out of the policy, one of the facets is that’s an important step and a critical step and I fully support that.”

When an assessment is required at the team level, that’s where Porteous comes into play. Besides being the CFL’s lead expert, Porteous is also the executive director of Ending Violence B.C. and co-chairwoman of EVA Canada.

Porteous is well-qualified, with decades of experience, and she played a lead role — along with Maychak and Freeman — in drafting the league’s domestic violence policy.

“What I always tell them to do is what I call a 360-degree collection and assessment of all the information that is available in the public domain,” Porteous said. “A lot of these guys have Twitter accounts and Facebook accounts and Instagram accounts, and you can learn a lot about somebody by looking at the kinds of things they posted over the last few years.”

Porteous would not say whether the Tiger-Cats contacted her about Manziel — she wasn’t permitted to talk about details of the case by the CFL — though she did say she has been involved in a number of these evaluations in the past.

“I do all of my work at the front end by flagging anything and everything that is a concern — any information that I have or am privy to is mostly public domain information and there can be quite a lot,” Porteous said. “There have been a number of players over the last couple of years since the policy has been in place that, because of these types of things… some teams have passed on people.”

She added: “I suggest to them to collect all of that information, and if they are still interested after looking at everything, including journalistic articles, both from the U.S. to Canada… I suggest that the GM meet with the individual on a one-on-one basis, ask him about his history of violence and look for things like remorse, look for things like not blaming the victim, look for things like taking accountability and, if at that point they are still interested in a player and they haven’t decided to take a pass, then the next step is the risk assessment.”

wfpsummary:

ON THE CFL RADARA timeline of Manziel’s history with the CFL

Aug. 25, 2016 – An ESPN story by NFL columnist Kevin Seifert states Johnny Manziel would be welcome in the Canadian Football League. Then-commissioner Jeffrey Orridge denies saying Manziel would be allowed in the CFL, and, in fact, says Manziel would not be allowed in the league.

Feb. 9, 2017 – A report from 3DownNation’s Justin Dunk alleges Manziel had worked out with the Saskatchewan Roughriders a month earlier. The Roughriders deny the claim, which would have put them in violation of league rules as Hamilton had already put Manziel on their negotiation list in 2012.

:wfpsummary

March 31, 2017 – Hamilton confirms they had retained the rights to Manziel on their negotiation list. Eric Tillman, general manger of the Tiger-Cats, provides glowing remarks of Manziel: “Guy that’s just electric, that could be one of the most exciting players in the Canadian Football League since Doug Flutie.”

Aug. 30, 2017 – Manziel is reported to have undergone a workout with the Tiger-Cats, along with a number of other players. Kent Austin, V.P. of football operations, informs media the team is not interested in signing Manziel at the moment.

Sept. 27, 2017 – Commissioner Randy Ambrosie, following a meeting with Manziel, says the league is not yet ready to approve a contract for the young quarterback. “After an extensive process of due diligence and an in-person meeting with Mr. Manziel, the Commissioner has decided that he will not register any contract for Mr. Manziel for this season. However, Mr. Manziel will be eligible to sign a contract for the 2018 season and, if Mr. Manziel meets certain conditions that have been spelled out by the Commissioner, the CFL will register that contract.” No other details released about the “extensive process of due diligence”.

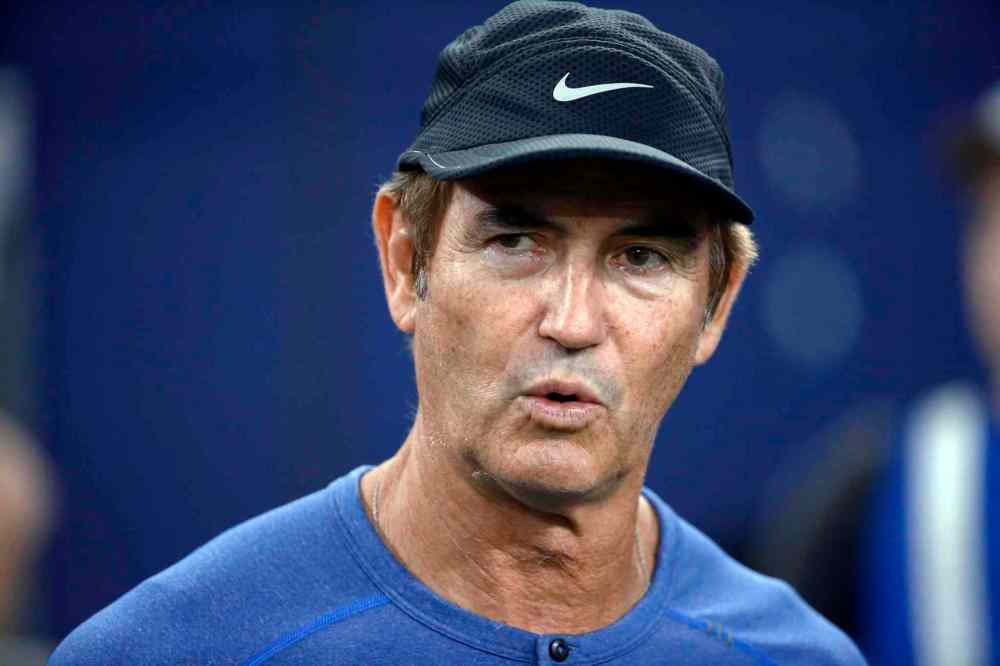

Dec. 8, 2017 – June Jones, just days after inking a three-year deal to continue as head coach of the Tiger-Cats, makes the claim to the hosts of CFL podcast, The Waggle, that Manziel could be “the best player to ever play up here.”

Dec. 28, 2017 – Ambrosie confirms he will approve a CFL contract for Manziel. The 10-day window is activated for the Tiger-Cats to offer Manziel a contract or risk losing his rights.

Jan. 7, 2018 – Hamilton offers Manziel a contract in order to buy more time for negotiations. TSN’s Dave Naylor reports the offer was a two-year “competitive” deal. By making an offer, Manziel remains on Hamilton’s negotiation list for another year.

Jan. 8, 2018 – Manziel and his agent Erik Burkhardt break the silence of contract negotiations with Hamilton by releasing a statement via NFL Network Insider, Ian Rapoport. In the statement, Burkhardt says, “we’ve made the decision to deal exclusively with Hamilton and give them until January 31st to work out a fair deal to make him their Quarterback. So that there will not be any ambiguity in regards to financial expectations, and so the public understands how seriously Johnny is considering this move, I will tell you that we believe ‘fair deal’ means on par with what Hamilton has paid their QB in recent years, despite not having much on-field success. If we cannot reach a deal with Hamilton by this date, we will turn our focus to several other professional options readily available to us.” Zach Collaros, who was Hamilton’s starting QB to start the 2017 season, was among the highest paid players in the CFL, set to make around $500,000.

Jan. 25, 2018 – Vince McMahon holds a press conference to announce the re-launch of the Xtreme Football League (XFL). Shortly after the announcement, Manziel tweeted @VinceMcMahon, “#XFL2020”, insinuating an interest in the league. But when asked about a number of free agent players, including Manziel, McMahon said: “When I said the quality of human being is very important and just as important as the quality of the player what I mean by that you want someone who does not have any criminality whatsoever associated with them,” McMahon said. “In the XFL, even if you have a DUI you will not play in the XFL. That would probably eliminate some of them, not all of them.”

Jan. 29, 2018 – Head coach Jones takes to Twitter to announce he’s back in Hamilton, hinting that a deal with Manziel might be close: “This week is going to be the one that sets the stage for a Grey Cup run… decisions on many things that will get us there… including Manziel… everyone is on board and team decision!!!”

Jan. 31, 2018 – Deadline set by Manziel’s agent arrives but no deal is reached. Manziel rights remain with Hamilton. TSN’s Farhan Lalji reports Manziel and the Tiger-Cats “are far apart as negotiations continue between the CFL club and the former NFL quarterback.” Manziel refutes report on Twitter, saying, “we asked for a ‘fair deal’ that’s it.”

If Hamilton were to do an online search on Manziel, the results would have been seemingly endless.

Details about allegations of violence — not only with women, but men, too — as well as information of other lawsuits, including trashing rental homes and cars, would have surely been enough for most teams to cut and run. That’s without considering Manziel’s well-documented time spent with the Browns, and how, at best, he could be characterized as prioritizing his social life over his professional duties.

Over the past few weeks since being cleared by the CFL, Manziel has posted a number of questionable posts to his social media accounts.

In one Instagram post, Manziel can be seen rapping along to song lyrics by Chris Brown, a celebrity with a high-profile history of domestic abuse. If the optics were not enough, the lyrics Manziel chose describe a tumultuous relationship with an ex-girlfriend and about “all them games we used to play.”

Despite what was or would have been discovered, it appears Hamilton is still interested in acquiring the young talent.

Maybe that shouldn’t be such a surprise.

Speaking at an Ending Violence Against Women — the Power of Partnership conference in late 2017, Porteous told a crowd of hundreds of people: “The Hamilton Tiger-Cats, not that long ago, without consultation by survivors that had been hurt by sexual violence or consultations with universities, hired somebody that was at the centre of the worst sexual assault scandal in U.S. college football.”

What Porteous was referring to was Hamilton’s decision to hire disgraced Baylor University head coach Art Briles midway through last season.

Briles was fired as the head coach of Baylor in May 2016, after it was alleged he played an active role in covering up a series of sexual assaults by his players. The details of what happened under Briles’ leadership include allegations of at least 52 sexual assaults committed by 31 players between 2011 and 2014.

Briles has always maintained his innocence.

The public firestorm that followed his hiring was fierce. Mobs gathered over social media, with angry messages raining down from across Canada and the U.S. The criticism was aimed mostly at the Tiger-Cats, but the CFL also became a target for frustrated fans wanting to know how something like this could be allowed to happen.

Briles was fired later that same day, with team owner Bob Young taking full blame.

“Someone mentioned to me that he was with Baylor and Baylor had a scandal, and while he wasn’t involved in the scandal, he was held responsible for it,” Young said in an interview with the Globe and Mail. “So I Googled it up. It looked pretty ugly to me. We had a conversation about it (and) as an organization we chose to move forward anyway.”

Scott Mitchell, CEO of the Tiger-Cats, also shouldered blame but appeared not to be as concerned with what his team had done. He initially said it was the public who played the main role in reversing the decision.

“Obviously, clearly, what was being contemplated was totally unacceptable to the general public… and the media,” Mitchell said. “What we thought was an opportunity to give somebody a second chance was clearly not acceptable to what previously had happened and what he had been involved with.”

In a stark change in attitude, Mitchell took ownership for the mistake the next day.

“Everything we do here demonstrates great community will. Everything we do in the community, we’re very, very sincere about it.”

While the Tiger-Cats certainly have a footprint in the community, and beginning this upcoming CFL season will unveil a similar program already adopted by other teams in the league that is aimed at preventing violence against women — it appears that when it comes to making football decisions, those same priorities might not always apply.

In light of the Briles fiasco, it would seem reasonable to assume the Tiger-Cats would be mindful of the potential embarrassment of making (or being perceived to have made) an irresponsible decision in the Manziel case.

And that it would appear to be a no-brainer the Tiger-Cats would be anxious to heed the advice of domestic violence experts in the local community — particularly in light of the current social-political sexual harassment climate and the views expressed by the league and its policies.

“That’s a fair statement,” Porteous said.

When reached by the Free Press, neither Hamilton Interval House nor Nicole Pietsch, a board member of EVA Canada and the co-ordinator of the Ontario Coalition of Rape Crisis Centres, had been approached by the Tiger-Cats.

“When a team is looking to do an assessment of someone’s personality and to gather case information from other treatment providers (at the team level)… that isn’t part of our protocol,” Porteous said. “That would be up to the team.”

The Tiger-Cats refused to answer direct questions regarding their vetting of Manziel, but issued the following statement: “While the discussions with Johnny Manziel and his representative have been very cordial and informative, there is nothing imminent and nothing to report. We will continue to due diligence and will have no further public comment on the matter as we move forward.”

● ● ●

Many of the domestic violence experts interviewed by the Free Press insisted, when dealing with perpetrators of abuse, there is no one-size-fits-all “right” answer. There is no foolproof examination to determine whether someone is fit to be welcomed into an unfamiliar community. There is certainly no way of guaranteeing someone won’t reoffend.

When pushed to expose more details about what took place with Manziel at the CFL level, Maychak revealed additional insight into a number of points that were previously released.

He said Ambrosie had met with Manziel last September, and was pleased with how the player conducted himself. However, Ambrosie was not prepared to allow Manziel to play the remainder of the 2017 season.

Maychak also said there was a criminal review meeting, “looking at all criminal proceeding he was under or faced.” Results from that search should have been concerning. Notwithstanding the two allegations of domestic abuse, a number of other lawsuits would quickly have come up.

What Maychak also made clear about the vetting process is Manziel was assessed twice by an expert in domestic violence, with time between the two meetings over the span of “several weeks.” What he wasn’t able to provide was who conducted the assessment or the results.

The expert’s assessment does not come with a recommendation as to whether or not Manziel should be allowed to play in the league, Maychak confirmed. Instead, the results, which are privy to only Ambrosie, suggest a classification as to whether Manziel is a “high risk” or “low risk” to reoffend.

Maychak hadn’t seen the sanctions attached to Manziel being eligible to sign a CFL contract, but had heard they were “stringent,” adding “and there may have been other stuff that I wasn’t privy to.”

Maychak said Porteous’s role in Manziel’s case, at least when it came to dealing with the league, was “minimal,” but she was responsible for recommending a doctor to perform an assessment.

While there could be a reasonable explanation for Porteous’s limited role, the CFL didn’t provide one.

It begs the question: why would the CFL decide to keep Porteous, considered to be the leader among domestic violence experts in Canada with an already established working relationship with the league, at arms-length in connection with one of their most high-profile cases?

Given the magnitude of publicity that comes with Manziel, wouldn’t the league bring all of its resources to bear?

According to a league source, Porteous had previously played a role in the evaluation of former NFL defensive end Greg Hardy, who, in 2016, was being courted by the Saskatchewan Roughriders following charges that included beating his then-girlfriend and throwing her onto a bed of guns.

Hardy was denied eligibility to sign a contract.

At the beginning of the 2017 season, when Justin Cox, then a player for the Roughriders, was charged with domestic violence, it was Porteous who was side-by-side with then-commissioner Jeffrey Orridge, as the two determined he posed too much of a risk to the community to be allowed to play another game. He would later be found not guilty, though his expulsion from the league remained in force.

Porteous wouldn’t confirm which doctor she chose for Manziel, but she did admit to having an expert — B.C.-based Harry Stefanakis — that she has used most often in the past and one she trusts.

“He specializes in working with men who abuse women so he knows how to deal with these guys,” Porteous said. “So if a club or the CFL want a risk assessment done, I basically pass it on to Dr. Stefanakis and then he does something that’s a behaviour risk assessment.”

Though Porteous admitted an assessment by Stefanakis goes “way further by doing personality testing”, she did say the two explore many of the same factors when performing an evaluation. Specifically, she listed off a number of questions that “are the kind of things, generally, that are considered risk factors for potential future domestic violence. And if someone has committed violence in the past, these are the kinds of things that are explored.”

Among those questions:

● Do they have a history of sexual assault or harassment?

● Does the person have a previous history of domestic violence?

● Have they been violent towards anybody else?

● Has the person ever been subject to a court order?

● Does the person have an alcohol or drug issue?

● Does the person have employment instability?

● Does the person have mental health issues?

● Has the person ever been suicidal?

“If in the public domain, I read an article about somebody and these kinds of things have been either been alleged or there’s been charges or convictions, I would advise the CFL to be very cautious and to definitely do a risk assessment,” Porteous said.

When asked if any risk be considered appropriate, Porteous replied:

“That’s a good question and one that I would share,” she said. “There must be something in there that is allowing (Ambrosie) to feel that he made the right decision.”

● ● ●

Perhaps the most glaring red flag against the veracity of Manziel’s assessment isn’t the questions the experts did ask, but the ones they did not. The Free Press was able to track down Crowley, Manziel’s ex-girlfriend, who confirmed no one from the CFL — nor the Hamilton Tiger-Cats — attempted to contact her.

In speaking with domestic violence specialists, many of whom currently sit on the EVA Canada board, the approach in handling these cases is consistent: the prime focus is always to ensure the safety of the victim. Not only is it paramount the victim be considered throughout the process of rehabilitation, they often can provide the most reliable evidence for and against the accused by sharing their experience.

“What they have taught me is that in a vast majority of these cases — not all, but in the vast, vast, majority — women don’t lie about this stuff,” Maychak said.

Talking with the victim can provide credibility for the accused.

If Manziel had shown remorse by issuing an apology to Crowley or shown some accountability by openly taking responsibility for his choices, it would have been significant, as those are described by evaluators as two of the most telling signs an accused is on the right track to changing his behaviour. Had the CFL reached out to Manziel’s victim, they would have found out neither of those signs was present.

“At first, I felt that I needed an apology to help me process the assault. When it wasn’t forthcoming, and I had more time to process his destructive nature, I realized that he needed the remorse in order to heal,” Crowley said. “He won’t change due to his denial of the events, his DNA, and the enablers he surrounds himself with. Me? I’m stronger now.”

The Free Press contacted Stefanakis, but he declined an interview due to a busy schedule. He did offer up people who had similar expertise.

One was Tod Augusta-Scott, who works at Bridges, a domestic violence counselling, research and training institute in Truro, N.S. His work has been published across Canada, Asia, Europe, the British Isles, and the United States. He is also the co-founder of the Canadian Domestic Violence Conference.

“Part of what I’m looking for in a guy is humility about the change process, that he’s able to put himself in his partner’s shoes, to show empathy,” Augusta-Scott said in a phone interview. “If a guy that can’t deal with the shame of the whole thing, minimizing the seriousness of the abuse or denying it all outright, those would be all warning signs, for sure.”

Augusta-Scott said a risk assessment can still be performed without the participation of the victim and often that happens. Victims of domestic abuse, he said, aren’t forced into these processes and they have every right not to take part. But when it’s possible, if the victim is willing to share information, she can play a crucial role.

“The only way you would know if, for example, the guy is actually taking responsibility, fully, is because he could absorb what she said the effects have been on her — and he could acknowledge that,” he said. “That’s really the test, and then he could make plans to make amends. But without actually hearing her input, he could make up what he thinks the effects were on her, but he doesn’t actually know.”

“At first, I felt that I needed an apology to help me process the assault. When it wasn’t forthcoming, and I had more time to process his destructive nature, I realized that he needed the remorse in order to heal. He won’t change due to his denial of the events, his DNA, and the enablers he surrounds himself with. Me? I’m stronger now.”– Colleen Crowley

When informed Crowley hadn’t participated in the Manziel case, and nor was she invited to, Augusta-Scott simply stated: “That’s a big problem.”

“This is just such a glaring example, when (the media) phone the victim and there’s been no attempt to engage her — that’s unforgivable,” he added. “If they haven’t reached out to the victim, even to see what’s going on with her, he’s not being invited to actually face the consequences and the effects of what he’s done.”

Though he understands the need for privacy in domestic violence cases, Augusta-Scott doesn’t believe every bit of information should be kept from the public.

“Just the fact that it’s all done in private makes the whole thing way worse,” he said. “It needs to be done in private initially, but the end game just can’t be that.”

For Augusta-Scott, rehabilitation is achieved when the accused is not only willing to heal himself, but also be concerned about the healing for the victim. He also said he understood many people in the public are willing to forgive and forget the actions of an abuser once they have “done their time,” whether through a jail sentence or other sanctions, such as anger-management classes.

“He may not be 100 per cent responsible for the relationship being terrible, but he is 100 per cent responsible for his choices, always,” he said. “There’s never an excuse for abuse.”

But if restorative justice, the path the CFL has taken, is to be effective, there must be follow-through — and not just consultation with experts. If a former abuser is going to be able to succeed at rehabilitation in the environment they are in, they won’t be able to do it themselves.

“The responsibility isn’t only not to do it again — and he may get that piece — but the idea that he’s not responsible to repair the effects of what he did, on the woman that he harmed, we should expect him to do that,” Augusta-Scott said.

“He could still be “low risk” not to do it again — and that’s an important piece, no one else is going to be harmed — but if he’s got all this collateral damage in the background, we should be lifting the bar and saying, ‘You need to take some steps to address that, (to address) the harm.’”

Despite the concerns raised, Ambrosie remains convinced the league made the right decision. But as he is about to begin his cross-country tour, he acknowledges the final verdict always rests with the fans.

“Our fans are very much part of the hierarchy of this league: they make everything we possible,” Ambrosie said in a statement prior to the tour’s kickoff. “I want to hear what’s on their minds and get their feedback on some of our plans. It is really important for us to be accessible, and accountable, to our fans.”

jeff.hamilton@freepress.mb.ca

twitter: @jeffkhamilton

Jeff Hamilton

Multimedia producer

After a slew of injuries playing hockey that included breaks to the wrist, arm, and collar bone; a tear of the medial collateral ligament in both knees; as well as a collapsed lung, Jeff figured it was a good idea to take his interest in sports off the ice and in to the classroom.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Friday, February 2, 2018 2:42 PM CST: Links, video added.