The meaning of sacrifice

By: Andy Blicq Posted: Last Modified:Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 07/11/2015 (3684 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Lying on a stretcher in a dressing station, suffering from serious wounds to his elbow and abdomen, Arthur Stanley Blicq faced a life-or-death choice: stay behind and be taken prisoner by the advancing German army or attempt the walk to a field hospital four kilometres away.

Dizzy from blood loss, he moved from his stretcher, stood up “… and tottered to the entrance,” he recalled in an unflinching memoir of his First World War experiences.

“Here, kid,” a corporal advised. “You can’t do it.”

“I can.”

“You’ll peg out on the way.”

“Sooner that than be a prisoner.”

The decision to walk probably saved my grandfather’s life. He almost certainly would have died of his wounds or been killed had he stayed behind. And later, confined for months to a hospital bed in France and then England, he escaped the grim fate of his battalion, the Royal Guernsey Light Infantry (RGLI). By April 1918, the Guernseys had suffered so many casualties the battalion was withdrawn from combat duty.

Unlike many others who never spoke about their time in the war, my grandfather shared his experiences with my brother and me. Pre-teen boys have a special reverence for old warriors, and after school on cold February afternoons in a rented house on Lanark Street where we lived with our grandparents, he spun sanitized yarns about his adventures in the trenches for a rapt audience of two.

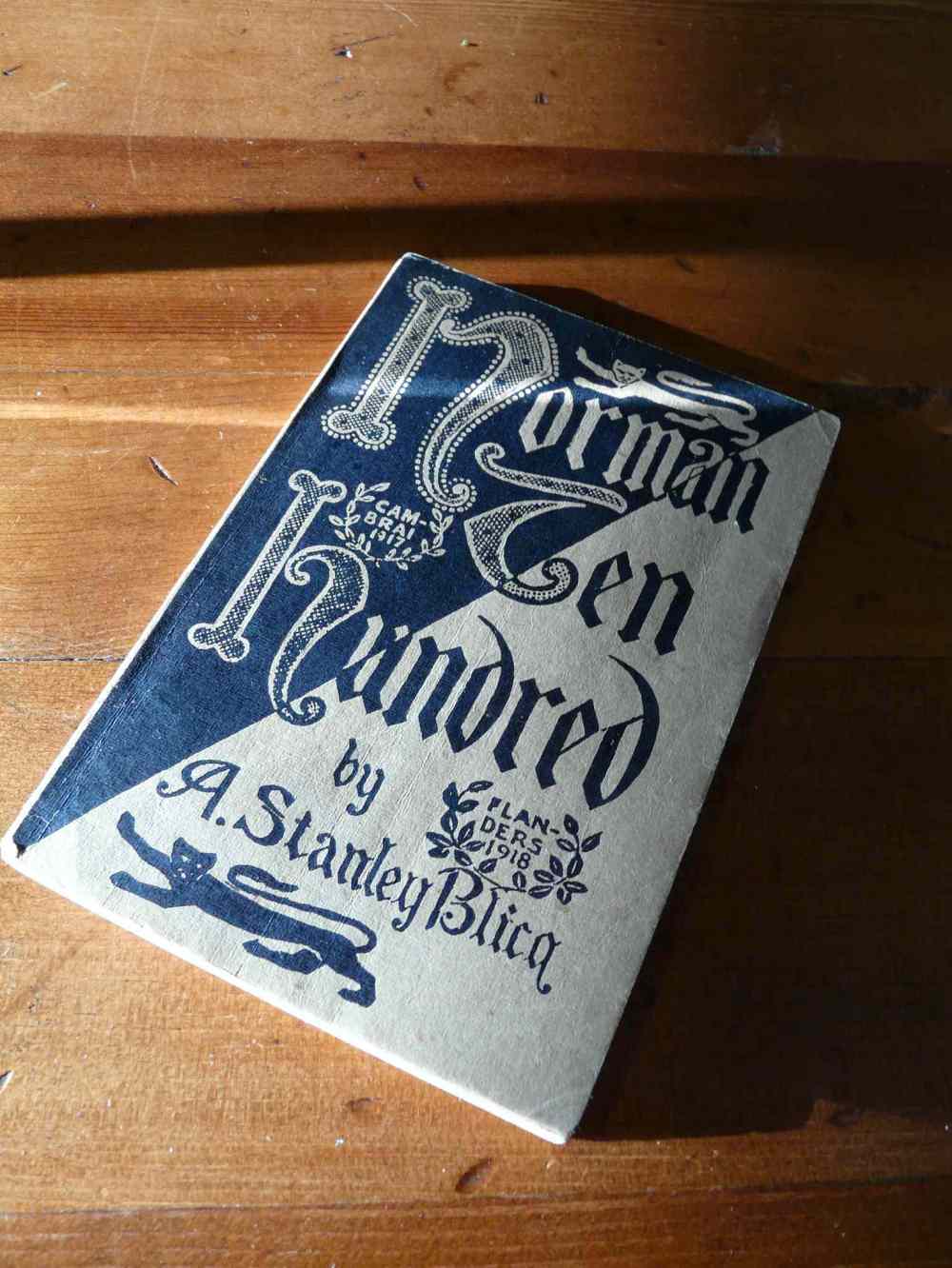

It wasn’t until after his death in 1976 that we learned the real story. My father found some of the last copies of my grandfather’s out-of-print book, Norman Ten Hundred, and gave them to us. Published in 1920, the memoir chronicles in vivid detail the horror and the humour that was a part of life at the front.

The “Norman Ten Hundred” were young men from the tiny, idyllic island of Guernsey in the English Channel who served in the RGLI. They were the descendants of the Norman warriors who supported William the Conqueror at the Battle of Hastings in 1066.

Many of the young men of the RGLI were a lot like the volunteers from the Canadian prairies — innocent farm boys. Many had never been off their island. Their first encounter with enemy shell fire near Langemark (then known as Langemarck), Belgium, in early October 1917, was a baptism of fire, according to my grandfather:

The Guernseys got the cream of it. Ground was churned up for yards and bodies buried weeks before were blown from their resting places, grinning white and hideous at the sky… The leading platoon caught it in their very midst, a ghastly heap of mangled flesh and shattered limbs were scattered to right and left. Two unhappy lads were blown to unrecognizable fragments. No words can convey the heart-rending cries of those whose bodies cringe and writhe from the hell-hot agony of searing shrapnel.

Many soldiers were driven to madness by what they witnessed under fire. It’s also clear from my grandfather’s book that, when the shelling stopped, others found salvation in the loyal company of their mates — and in laughter.

Cookie, black and grimy from head to foot — the only condition in which he really felt at home — prepared the removal of his cookers.

“I didn’t ‘alf ‘ave the wind up,” he confided (to) me afterwards, “about that there last dinner; becos, you see, a Jerry shell wot burst close chucked a great chunk of mud into one of them cookers. Wot was I to do? Couldn’t throw away the grub… didn’t ‘ave no more so I just stirred it all up. Anyhow… it made it thicker, and they sez it was ‘trey bun.’ ”

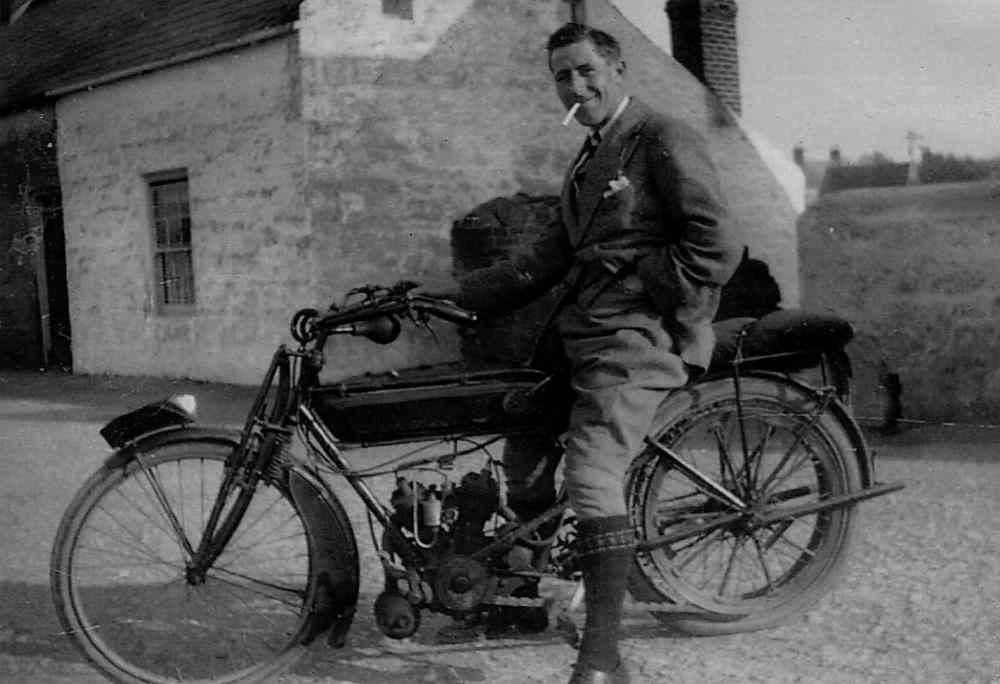

My grandfather had an ear for dialogue and an eye for detail — something that served him well after he recovered from his wounds and returned to the island. He became a sports reporter for (and, later, an editor of) the island’s newspaper, Guernsey Press. But like so many of his generation, he would not be left to live out his days in peace.

By 1940, the Nazis were on the march.

Britain informed the islanders it would not be able to offer them a defence. Parents had just hours to decide whether to keep their children home (50 kilometres from the coast of France) or to send them to England (120 kilometres to the north).

My grandfather knew what life under the heel of a jackboot would mean for a journalist and a war veteran, and for his three sons now approaching military age. He went into the garden and buried a box full of copies of Norman Ten Hundred, so the invaders would not be able to identify who among the islanders had military experience. He then loaded his six beloved, champion golden spaniels into the car and, with my father, then 15, drove over to the island’s humane society.

“The kennels were absolutely full with islanders’ dogs,” my father (now a spry 90-year-old) told my brother and me on a recent pilgrimage to Guernsey, an exploration of our family’s history in both world wars.

“I saw a sign on the wall listing how many dogs that had been destroyed for their owners, and it was at that moment I realized what was going to happen to these dogs. But I never mentioned it to my father. I just didn’t dare open it because it would just have been too painful for him.”

There was no choice. There would be no one left behind to care for them.

In the summer of 1940, my grandparents embarked for Canada, becoming one small stone in what I believe to be a founding pillar of Canadian life. Escape from the cauldron of human conflict to the dream of a better future under the Maple Leaf is an experience shared and remembered by thousands of Canadian families.

Poverty is a part of that experience, too. Most refugees arrive with next to nothing, and our family was no different. Knowing they had relatives in Winnipeg, my grandparents chose its forbidding winters as the place to stake their future. With his newspaper experience, Stan Blicq became an editor at the Winnipeg Free Press, welcomed onto the staff by legendary editor-in-chief John Dafoe Sr.

He never returned to Guernsey.

Two years after my grandfather’s death, I started my journalism career as an intern in the same newsroom on the fourth floor of the historic former Free Press building on Carlton Street. One of my greatest regrets is he didn’t live long enough to see me take my place there. But I’ve never forgotten him nor my bucket-list promise to one day return to our family’s fabled island and make a pilgrimage to the places in Europe where my grandfather and the Guernseys fought their war.

Once underway, that pilgrimage quickly became a mission: to get his all-but-forgotten eyewitness account — his story all-the-more valuable now that there are no eyewitnesses left alive — onto the modern public record.

_CORRECTED.jpg?w=1000)

That mission began in Liz Walton’s living room on the island of Guernsey with a better understanding of the word sacrifice — a word so often attached to the First World War it has almost lost its meaning.

“I’ve seen newspapers of the period, and you’ll see the whole of the front page with just name after name after name of the missing, and that must have been the worst, not knowing whether they were alive or not,” said Walton, adding it could take weeks or months to confirm what had become of husbands, brothers and sons.

In the end, the island of 40,000 souls lost about 1,500 of its young men. Walton said in the years following the war the population declined because there were so few men of marrying age.

“Women could no longer expect to marry, have a home, have children. They had to find other ways of life. There was a whole generation of single women school teachers.”

Walton became a leading expert on the island’s war years after her first visit to a war graves cemetery in France.

“That night I dreamt that there was a man standing where every one of the headstones had been. And that’s what brought it home to me. They weren’t just rows of crosses. They were representing real people,” she said, adding to go to the battlefields of Belgium and France “really is a life-changing experience.”

It would become that for us, too.

From Guernsey, my wife Cindy and I travelled by ferry and then by car to Nieuwpoort, Belgium, where we rented a live-aboard boat named Sheba, with plans to head south through the Belgian communities and farms levelled by four years of shellfire and subsequently rebuilt.

As we prepared to leave, outfitter Rick Hilleweg had these parting words for Canadians who have never seen a country torn apart by war.

“Believe me, you are lucky people,” he said, adding tonnes of unexploded bombs and shattered steel are ploughed up by Belgian farmers every spring.

“It’s one big graveyard here,” he said. “Every square metre is spilled with blood.”

Hilleweg said an increasing number of foreigners are making a First World War pilgrimage by boat — navigating the historic canals that snake along what was the front line. Piloting a nine-metre vessel and navigating the ancient series of channels and locks was challenging, but, for a couple from the Canadian prairies, the landscape seemed oddly familiar. Miles of agricultural flatlands interrupted by small villages and towns, and all along the canal banks a blaze of wild flowers — especially blood-red poppies.

After mooring Sheba in the small city of Ypres, Belgium, we rode rented bikes along the extensive network of trails that line the banks of the canal and accidently stumbled across Essex Farm Cemetery.

Here, in 1915, Canadian physician John McCrae wrote his poem, In Flanders Fields, outside an advanced dressing station where he fought to save as many of the wounded as he could.

Reading the poem aloud from a plaque, I struggled to contain my emotions, remembering reciting it as a boy during Remembrance Day ceremonies at Sir John Franklin School.

The poem didn’t mean much to us then, but standing among the rows of headstones, some of them marking Canadian graves, and outside the remains of McCrae’s field hospital, I felt its power, especially at the foot of the grave of Valentine Strudwick.

His mother called him Valentine because he was born Feb. 14. Serving in Britain’s 8th Rifle Brigade, at age 15, he was killed by shellfire on Jan. 14, 1916. His grave in Essex Farm Cemetery has become a shrine to innocence lost and young lives squandered. Small wooden crosses, Canadian flags and messages left by visiting school children surround his marker.

_CORRECTED.jpg?w=1000)

When children came to join up, military recruiters just looked the other way, said Belgian tour guide Rene Degryse.

“They needed everybody and there were so many volunteers in 1914,” explained Degryse. “Everybody was welcome.”

“Too young. Way too young. Haven’t even started life. It’s very sad,” said Natasha Cappellari. She and her husband, David, brought their four teenage daughters all the way from Melbourne, Australia, to Essex Farm Cemetery “just to see how lucky they are.”

“I think it’s important for everyone to come over here at some point in their life,” added David. “You can’t even imagine what (the soldiers) must have gone through.”

Cindy and I were there for my grandfather’s story, but it is impossible not to be swept up in the accounts of what happened to all the others, too. The Australians and the Canadians are well-remembered in Europe. Their stories told on monuments and in museums, their remains left to lie forever under simple white headstones in immaculately-kept cemeteries that seem to be around every turn in the road. For many of the dead, there is no grave marker.

In rebuilt Ypres, we made our way downtown to the nightly ceremony at the imposing Menin Gate — a memorial to the 54,000 Commonwealth soldiers killed fighting in the area and whose bodies were never identified or found. Their names are listed on panel after panel. Almost 7,000 of them are Canadians.

Every evening, buglers from the Ypres fire brigade play the Last Post at the gate while a solemn crowd (which can swell to 2,000) looks on. On the night we were there, many fell to weeping while the buglers played and wreaths were laid. Each night, one of the missing is singled out; his story told by the volunteers who have run the ceremony since 1928.

That night, volunteer Paul Foster told the story of the Dunlop brothers of Frank, Alta. Coal miner Daniel Dunlop and his three sons enlisted; only Daniel Sr. survived. His sons have no known graves and their names are carved into the Menin Gate. The youngest, John, was just 16.

Foster said the size of the nightly crowds shows that despite the fact all the veterans are gone, interest in the war is not fading.

“We get an enormous number of people from Canada,” he said. “More people are visiting the cemeteries and the memorials, such as this magnificent one here, every single day of the year.”

Leaving Sheba and Belgium behind, we switched to a rental car and headed south into France travelling through the battlefields of two world wars, shifting from the freeway to the side roads that define the lush green farm fields and pausing wherever the Guernseys saw action.

At the Battle of Cambrai in 1917, my grandfather witnessed one of the first successful deployments of tanks — a story he often told. The Guernseys were elated by the huge gains made with the help of this new weapon, but were bitterly disappointed when the hard-won ground was soon lost in the endless stalemate that was the Western Front.

Today, so often it is the dead that get the attention, but for me and Peggy Barr of Kelowna, B.C., it is the suffering of those who survived that captures our imaginations. We met while exploring a restored trench in Passchendaele and compared notes.

“He was a lovely, gentle giant,” said Peggy, describing her great-uncle who served in the Canadian military, dragging artillery pieces through the mud at Passchendaele. “They sometimes were standing, I remember him saying, in mud and muck for days. You can imagine what that does to your joints.”

The restored trenches at Passchendaele seem like luxury compared to the conditions my grandfather describes in his book — men taking shelter in shell holes, with no contact with others for days at a time.

The failure of water supply reaching these outposts increased an already severe existence. Someone would go “over the top” crawl to and fill water bottles up at the nearest shell hole. A body or limb might be at the bottom. Who cares! The water is rank, putrid evil-smelling; but the fierce-mad craving for drink is not to be denied.

Peggy said her great-uncle suffered greatly as a result of his service. For the rest of his life, he was plagued with back and joint problems. My grandfather lived with his injuries, too. I remember him at the dinner table, struggling with his knife and fork, his left arm permanently damaged by the bullet that passed through his elbow.

But it is what the war did to their souls that fascinates. Peggy’s great-uncle and my grandfather became the gentlest of men — it was as if, after the war, there was not a gram of violence left in them. Their reward was the worship of their grandchildren and great-nieces and great-nephews.

“We loved him. We remember him well,” said Peggy.

Places in this story

And perhaps that’s why Peggy, I and so many others wandered the old trenches, battlefields and cemeteries trying to make sense of the experiences our elders had a century ago. We remember their innocence and cheerful bravery with tenderness and wonder.

“In many respects, it feels like some of them just threw their lives away at the whim of people who were making some very idiotic commands and calls,” reflected Peggy. “On one hand, I wish they hadn’t gone. On the other hand, I admire them greatly for their patriotism and their courage.”

The young Germans who served on the other side were undoubtedly brave, too. But along with more than two million dead, their nation had to swallow the bitter medicine of defeat. At Neuville-St. Vaast German War Cemetery in France, 44,000 of their dead lie in mass graves. As far as the eye can see there are black crosses, each bearing four names. Some bear the Star of David. It is an appalling sight.

Nearby, we met Johannes Linden and his son from Bonn, Germany, who were on their own pilgrimage of discovery. Johannes said the war remains a deep wound for Germans and he condemned the generals and the ruling classes who put their egos before the many young lives lost.

“People tend to forget that the young people pay the blood toll. Not the old ones,” he said. “A whole male generation was wiped out in that war.”

It became a fight to the finish, ending only when Germany no longer had the resources to continue. But not before a combined total of eight million soldiers had died at the front.

On June 2, 2015, I stood on a quiet street in a suburb of brick houses across the river from Masnières, France, and read aloud from my grandfather’s book. It was here he could so easily have become one of the fatalities had he not attempted to walk to freedom. And it was here I made one final, astonishing discovery that completes the circle of our family’s war story.

A plaque commemorating the sacrifice of the Fort Garry Horse regiment stands on the north side of the scenic St. Quentin Canal. It appears the Guernseys served in the Battle of Cambrai alongside the Fort Garry Horse (from Winnipeg) and the Royal Newfoundland Regiment.

We will never know whether my grandfather met any of them; whether they shared a meal or a cigarette before he was wounded Nov. 30, 1917. I like to imagine that they did.

And it was here the Guernseys and the Newfoundlanders made courageous stands against overwhelming odds, losing young men both islands simply could not replace. My grandfather described what happened:

The Germans launched a heavy offensive for the re-taking, wave and wave, line after line, moving ponderously forward. The Norman (Guernsey) rifles and machine guns shrieked out lead in a high staccato until the advance slackened, wavered and fell back. Hun (enemy) artillery showered shell, gas and shrapnel over every yard of ground. For a period the Normans fell in dozens everywhere. The canal in places was stained red, and Norman bodies drifted twirling away on its fast-running waters before sinking.

Although he was badly wounded, in the final words of the Norman Ten Hundred, my grandfather describes what it meant to be one of the lucky ones who survived this cruel lottery.

Farewell, a sad farewell to for ever lost echoes of ten hundred voices raised in rallying chorus to the swing of square shoulders and the ring of manly feet.

The ‘old order changeth.’ Away from the strong fray… free life… laughter, glamour, song… the Great Open… Back to the little world, its little things, to its little life.

_corrected.jpg?w=1000)

On our final day of travel in France, we drove up to the towering Canadian monument at Vimy Ridge, gleaming white against a steel-blue sky. We stood next to the solemn statue of Mother Canada and looked north over the serene, green patchwork that rolls out to the horizon. Thirty-five-hundred Canadians died here and 7,000 were wounded.

“This monument is so huge. It finally, for me, speaks to the enormity of the war and the losses,” Cindy said quietly. “It is a monument where you feel you can grieve.”

But only by coming here and seeing it for yourself, can you truly do that.

Stone and statue help us grieve and remember. The Norman Ten Hundred is a monument of a different kind — a window into the character and the experiences of those who were called upon to serve in the “Great War.”

Many veterans choose to leave their wartime experiences on the battlefield or bury them deep in their memories. I speak to them now as someone who has been given, not just a book and a story, but a precious gift of understanding and memory. When I read his words, I hear my grandfather’s voice again.

And so to our living veterans of Ortona and Kapyong and Kandahar, I say: give up your silence. Release your stories to us, so we may truly know what you, and Canada, have done. Write them down or simply tell your children and grandchildren what happened.

Your first-hand accounts will breathe truth and life into history. They are gifts that allow us to truly honour your service and to remember those, like all the Guernseys, who rest forever among the poppies in Flanders Fields.

Andy Blicq is an award-winning journalist and documentary maker. He worked at the Winnipeg Free Press from 1978 to 1985. He lives in Gimli.

See ye Masnières canal a’flood

And where yon green graves lay?

There Norman warriors fled to their God

Ne’er more to glimpse the day.

But writ there, first, a name in blood-

Norman Ten Hundred.

At Doulieu, the night birds flit

Across yon blue-grey water.

And at dusk ghost warriors sit-

Wraiths of a fearsome slaughter.

There too in blood the name is writ-

Norman Ten Hundred.

And thus there the battle’s flame

Laid men out fast and low,

So young Sarnia died, but Fame

Cast o’er their graves its glow,

And honours wove about the name

Norman Ten Hundred.

From Norman Ten Hundred, by A. Stanley Blicq,Guernsey Press, 1920