Forewarned is forearmed Churchill's council has unanimously approved a climate-change action plan prepared by the town's federally funded adaptation co-ordinator

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 23/10/2020 (1871 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Climate change will have widespread effects in Churchill, but in addition to the impact on wildlife and how it will alter the course of the town’s economy, it will also have a substantial impact on the town’s infrastructure as permafrost thaws.

In mid-September, town council voted unanimously to support a strategy drafted over the past year-and-a-half by Trevor Donald, Churchill’s climate-change adaptation co-ordinator.

Donald’s position was funded by the federal government, as it has done in smaller communities across the country without adequate tax bases to support similar positions.

“It’s hard to really find communities that have done adaptation planning to compare to that are the size of Churchill,” Donald told the Free Press.

The plan lays out priority action areas and emphasizes priorities such as reconciliation and community consultation.

“This climate-change adaptation plan is just the first step to Churchill understanding its risks, vulnerabilities and opportunities,” the document reads. “With the chronic and acute physical risks of climate change looming, policy-based solutions alone will not be enough to tackle the impending climate crisis. This plan simply allows for guidance so that the town can make the right actions and implement a mix of policy and planning projects with infrastructure-based projects to build resilience.”

For Mayor Mike Spence, it’s a critical step forward in understanding exactly how big the challenges are.

“Climate change is right before us and it’s not an easy fix,” he says. “So, if we can come up with a ‘master plan,’ so to speak, to adapt to doing things a little differently, great.”

Projections for Churchill

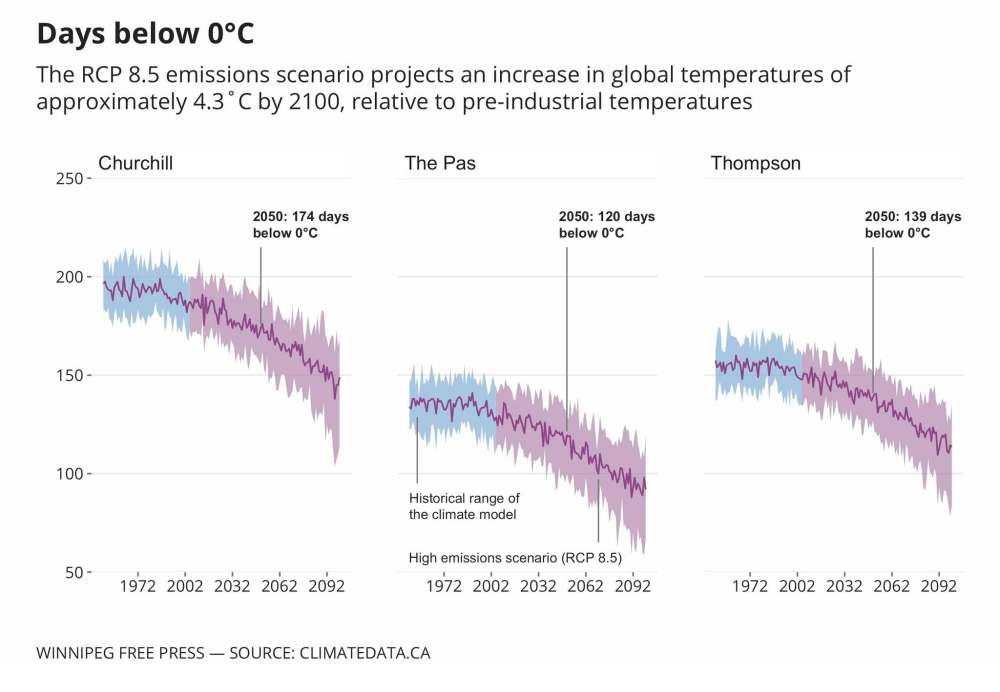

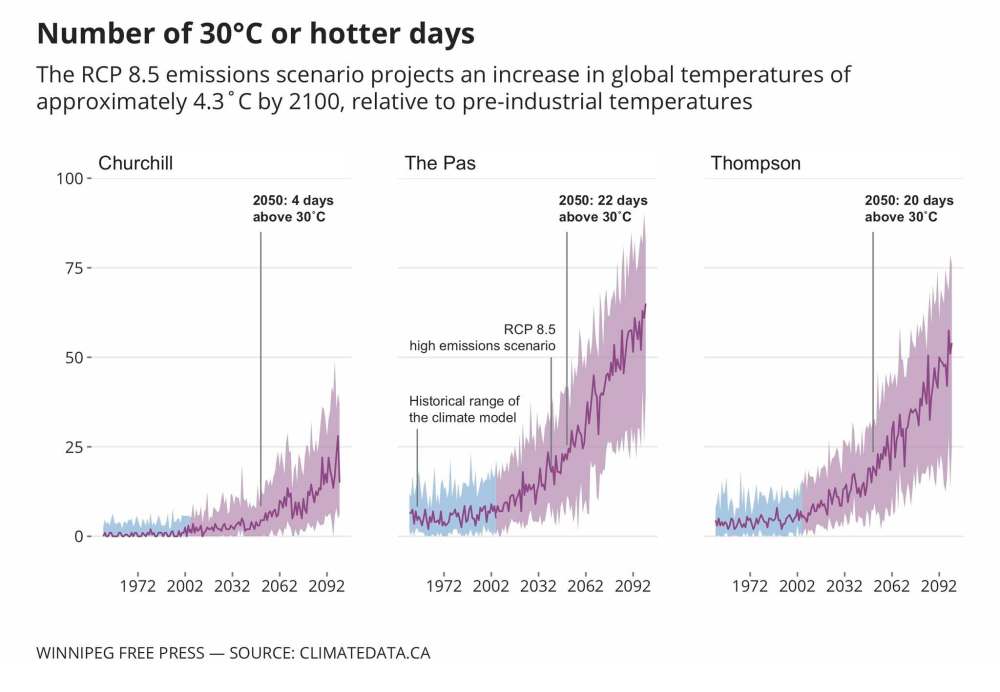

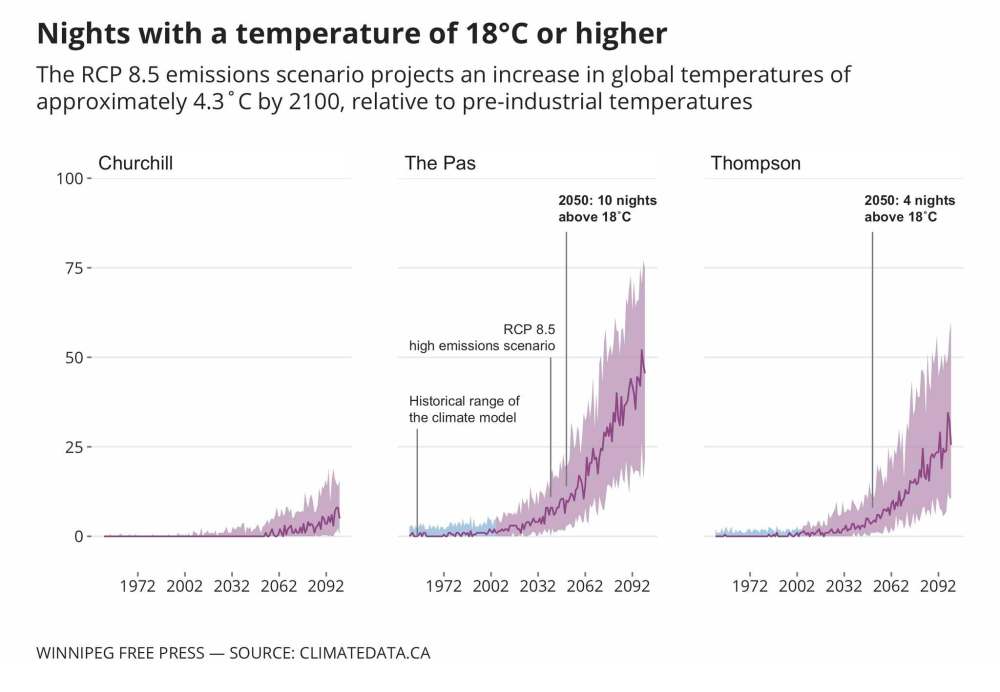

In a scenario where emissions continue at status quo levels, Churchill is expected to experience fewer very-cold days. Currently, on average, the town has 51 days that are -30 C or colder; by 2050, that is projected to be 25.7 days.

The annual average temperature is currently approximately -4.8 C. By mid-century that is projected to rise to -2.3 C and by the end of the century, 2 C, according to data provided by the Prairie Climate Centre’s Climate Atlas.

Additionally, precipitation is projected to rise by 10 per cent. And the number of days where wind speeds exceed 30 and 50 km/h is rising.

Permafrost hazard mapping

The surface of the ground thaws each year in Churchill, but the ground beneath is perpetually frozen, known as permafrost. With continued warming, the layer that thaws grows, sinking deeper into the ground each year and the rate is accelerating. The process, which is irreversible, results in increases in greenhouse-gas emissions through the release of carbon and methane.

It also destabilizes structures built above ground as it heaves and shifts with the thaw. News stories from Siberia during the past few years have reported huge craters opening up in the earth as a result of the thawing permafrost.

Permafrost thaw is a problem across northern Manitoba.

While the northern territories have more up-to-date information on how the thaw is occurring and where the most at-risk areas are, Manitoba doesn’t have such information.

A spokesperson for the provincial Department of Conservation and Climate directed questions on the issue to the issue to the federal government.

While the northern territories have more up-to-date information on how the thaw is occurring and where the most at-risk areas are, Manitoba doesn’t have such information.

A spokesperson for the provincial Department of Conservation and Climate directed questions on the issue to the issue to the federal government.

“In northern Manitoba, the impacts of climate change are starting to be felt on construction projects on reserve, and are still being evaluated. Thawing permafrost can add to the challenges of getting materials to and working at construction sites, and can also make geotechnical studies out of date,” a spokesperson for Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada told the Free Press.

“Climate change has also impacted the winter road network in northern Manitoba, creating less reliable freezing conditions and potentially resulting in a shorter winter road season, which is usually about two months, from mid-January to mid-March. To address this, Canada and Manitoba are partnering to create new winter road routes, building bridges where needed, in order to move winter roads off of bodies of water and onto land wherever possible. Canada and Manitoba have invested $1 million to date, cost-shared 50-50, however future work and investments are anticipated.”

— Sarah Lawrynuik

Churchill’s plan includes an inventory and assessments of vulnerabilities and prioritizing maintenance. It would also involve updating local best practices for building.

“You need building codes that are specific to the climate,” Donald says. “‘If you’re building on permafrost, this is how you ought to do it.’ So, we’d be looking at changing the municipal building codes to reflect that.”

Donald also emphasizes the need for the community to understand where their risks are most acute, and is working to try to leverage different institutions, such as Manitoba Hydro, to procure a permafrost hazard map for the community. While the territories had such mapping done a decade ago, nothing similar has been undertaken at this point in northern Manitoba.

A Manitoba Conservation and Climate spokesperson responding to a Free Press inquiry didn’t know what permafrost hazard mapping was and directed questions on the subject to the federal government.

Donald also says better drainage in the community is very important, as stagnant water thaws the ground faster. The document also requests better understanding of how permafrost thaw might impact water quality in the community.

“If you have poor drainage, you’re going to have poor stability, due to permafrost thaw,” he said.

Emergency management planning

Donald points to the 2017 Hudson Bay Rail Line washout as a prime example of how vulnerable the community is to extreme weather events; unprecedented winter snowfall was followed by overland flooding in the spring.

Among the priorities for addressing this key area of concern are: creating a public notification system, updating emergency response procedures to anticipate more frequent and more intense weather events and addressing food insecurity in the region.

Sea levels

Unlike countless coastal communities around the world, Churchill — and much of Canada’s North — is not at risk from a rising sea level. In fact, it’s falling.

The frozen land of the North is decompressing and lifting, and has been since the last ice age about 16,000 years ago in a process called glacial isostatic adjustment. It’s estimated that the sea level has dropped near Churchill by roughly one metre over the past century.

What can be learned from the impact of COVID-19?

The global pandemic and climate change are different, yet both demonstrate vulnerabilities within a community, the plan says.

“The communities most vulnerable to the climate crisis are many of the communities most vulnerable to the coronavirus. Infrastructure in the North, for example, is lacking to handle a large crisis or emergency,” it says. “Simply put, climate change is a threat multiplier that makes many of our problems worse and impacts the health and safety of our communities.”

Education

The strategy lays out education and awareness initiatives as a key priority for the community at large and for town councillors and employees.

Funding in smaller communities

One of the biggest issues with creating an adaptation strategy in Churchill is that there isn’t a lot of money to throw at the problem, Donald explains. As a consequence, the adaptation strategy is written in a flexible manner so that when funding opportunities open up from the province or from Ottawa, Churchill can take advantage of them.

The problem, from a local government perspective is, “we’re all in the same boat,” Spence says.

Climate change will impact every community in one way or another, and it’s a matter of where and how funds are awarded, he says, adding he anticipates that after waves of pandemic-recovery money is distributed, it will be difficult to find any for adaptation measures.

For longer-term projects, relying on other levels of government is still rife with problems, but Donald hopes it will be possible through a patchwork approach. He adds that it would likely be more fruitful for a more co-ordinated effort to be taken across the region because of Churchill’s small size.

Why no plan to curb emissions?

The adaptation strategy focuses solely on how the town will change operations and activity in preparing for the impacts of the changing climate, not how the town will lower greenhouse-gas emissions, which is a mitigation strategy. That is principally because the climate will continue to change for years to come with or without emissions reductions; it is only the severity of the changes that have yet to be determined based on how fast global emissions are reduced.

As a northern community, Churchill will be disproportionately affected and needs to be ready, Donald says. And with limited resources, the town needs to focus on adaptation.

‘Demonstrating reconciliation on the ground’

Pursuing a strategy with reconciliation as a pillar is critical for the community, Donald emphasizes.

“Indigenous people in Canada are just starting to regain traditional practices and cultural aspects that were meant to be eliminated. While Indigenous peoples are often considered more vulnerable, they do not seek to be seen as vulnerable but rather seek reconciliation and a restoration of health, wellness, self-determination and sovereignty,” the plan says.

The strategy calls for Indigenous people in the community to be given “meaningful” roles and to be included in the decision-making processes. All Indigenous stakeholders are to have the space needed to express their concerns, which should be “centre stage,” the document states.

sarah.lawrynuik@freepress.mb.ca