Tales of tragedy, triumph abound

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4 plus GST every four weeks. Offer only available to new and qualified returning subscribers. Cancel any time.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 28/04/2012 (4693 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

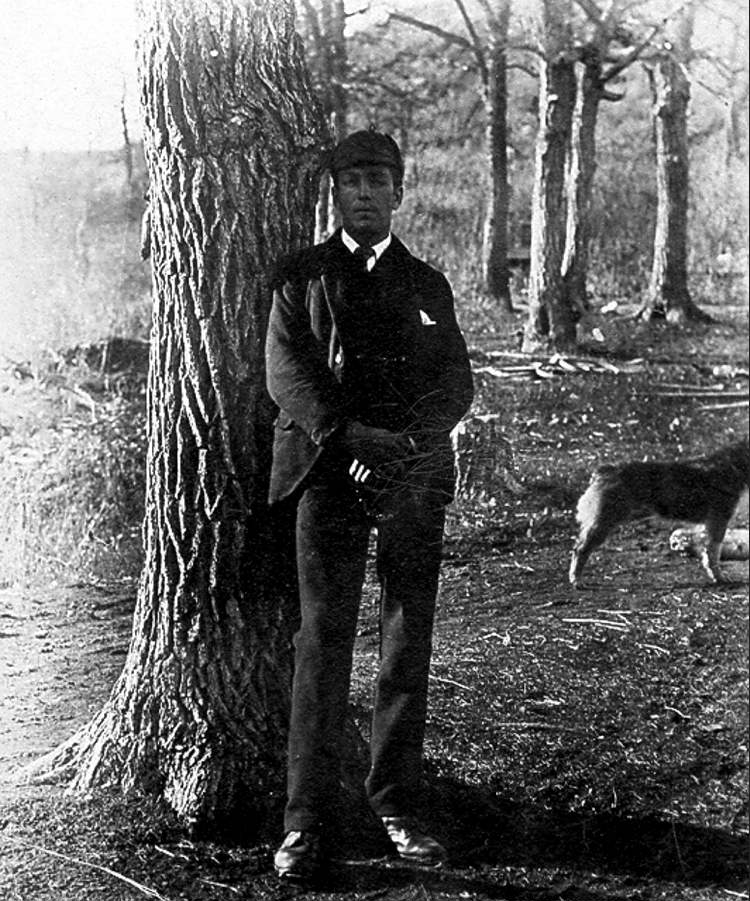

William Cheesman

THE fate of William Cheesman shows how fast and how hard families fell before there was a social safety net, and how tough was the struggle to bounce back after hitting rock bottom.

William was born in 1878 to a middle-class family in London. He was 11 when his father died at age 57. The family was forced to move to Notting Hill, then a crime-infested slum. His mother died the next year.

His younger siblings were placed in convents and orphanages. William, 12, was left to survive in the streets.

In 1893, he was arrested for trespassing, handed over to Dr. Barnardo’s home for destitute children.

In 1894, at age 16, he boarded a ship with 542 Home Children bound for Canada. William was sent to Barnardo’s Industrial Farm near Russell. It was the remote place older boys, who’d grown up on the streets of London and were “rougher” in character, were sent, said William’s granddaughter, Lori Oschefski, who has researched his story.

The idea was to move them far from the lure of cities such as Toronto. In Russell, they were trained to farm so they could be hired throughout the West or homestead and become successful farmers.

Shortly after William arrived, he was placed in a work “situation” as a general farm hand for $55 a year.

In 1896, William wrote to Barnardo’s saying he was leaving. He complained about his treatment by the farmer and not getting his wages; the farmer complained about William’s conduct.

William was sent to work for another farmer who wrote to Barnardo’s that William “is well and is a splendid boy, a credit to the Home (Barnardo’s) of which he speaks so highly.”

A short time later, William took off again.

He ended up working for John P. Jones’ farm in Brandon.

In 1906, he homesteaded near Saskatchewan and built a sod house for his bride, Annie, who arrived from England in 1912.

Their farm wasn’t a success. By 1917, they already had two children when their twin girls were born. The farm was sold, and the Cheesmans moved and become tenant farmers. Their fifth child was born.

In 1919, the family returned to England but just for a break. Four months later, William returned to Canada alone to work at the farm. In 1921, he went back to England.

In 1922, when Annie was pregnant with their sixth child, William returned to Canada to sell the family’s belongings. They never heard from him again.

Annie and her six children were left destitute in England. They entered the Kingston Union Workhouse where she had to forfeit her rights to the children. She had a nervous breakdown, and the kids ended up like their dad — Home Children sent to work in Canada.

George H. Davis

IN London, George H. Davis’ father died and his mom abandoned him and his siblings when he was 15.

At 16, the orphan was sent to Manitoba to work on a farm near Cartwright.

“I tried to find out how he got here,” said his grandson, Bill Brisbin in Winnipeg.

“There were several other agencies that did that sort of thing,” said Brisbin. “None of them had a record of him. It turned out to be a dead end.”

However he got here, George succeeded in Manitoba. He worked on the farm raising horses and growing vegetables then taught himself French and put himself through university. He died a wealthy, successful lawyer in a nice big house in Winnipeg near Crescentwood’s Peanut Park.

The story of George Davis and the Home Children resonates with his great-grandson, David Rattray.

“They did not have a nice upbringing,” said Rattray in Winnipeg.

“It must have been like Lord of the Flies.”

His sons, ages 15 and 17, are close to the age his great-grandfather was when he came to Canada.

“I look at my son and think ‘How would that work?,’ ” said Rattray. “In those days, you had to move forward,” he said. “There was nothing to go back to.”

William Henry Disson

WILLIAM Disson was just eight when his mom’s breast cancer spread and she could no longer work as a machinist to support them.

His father had abandoned them when William was a baby. She arranged for William to be taken in by Dr. Barnardo.

“William is a nice boy, and has been well trained,” the orphanage noted in his file. At age 11, he was sent to work on a farm near Huntsville, Ont. Correspondence kept by Barnardo’s said William was plagued with ear infections. He wrote letters to his mother and was disappointed to never receive a reply. In his mid-teens, he went to work at a Rainy Lake lumber yard in northwestern Ontario before visiting the Barnardo Industrial Farm. At the end of his Barnardo term, he moved to Winnipeg’s West End, worked as a delivery driver, got married, had kids and retired from CN Rail in 1946.

After growing up with so many ear infections, William ended up nearly deaf and isolated himself, reading Western novels and shutting out the world. His memory started to go and his wife, Lillian, could no longer care for him. He died in 1968 and is buried in Brookside Cemetery.

Alexander McKean

Alex McKean, who farmed in Miniota, wrote about coming to Canada at age 11 with his brother, nine, then being separated.

“Dr. Barnardo was at the ship to bid us farewell when my brother David and I sailed for Canada in 1905. David was nine and I was 11. I remember that we were in the back of the ship, probably third class. The voyage lasted between two to three weeks. We were stopped for at least one day by icebergs.

“On our arrival in Canada, we went by train to Winnipeg and spent about two weeks together in the home. There, we were told we would be separated. I remember we crawled into bed together that last night and cried with our arms around each other until we went to sleep.

“I was sent to a farmer near Miniota. One day, about three years later, my boss took me to a country fair. I was wandering around and I saw this boy who looked familiar. I walked up to him and said ‘I think you’re my brother.’ When my boss came to say it was time to go home, I said ‘I’ve found my brother.’ So he gave us two bits and told us to go and buy something with it. We bought some bananas and sat on the railway ties and talked and talked. My brother lived at Beulah, a village about nine miles north from my place.”