Chamber-made

From busting Stones to spying on spies: How a British cop became a top Manitoba executive

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 28/04/2012 (4985 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

He helped bust one of the world’s biggest rock stars — Rolling Stone Mick Jagger — and spent more than two decades spying on spies and terrorists for the RCMP and CSIS.

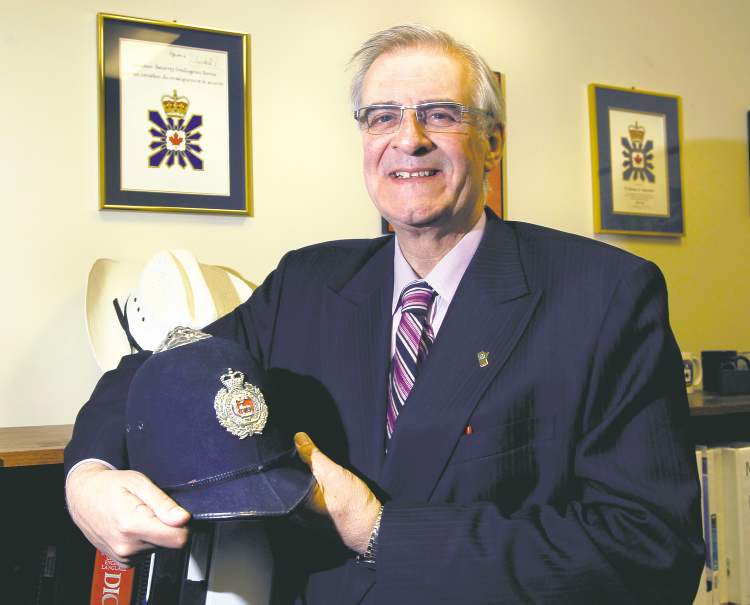

Those aren’t the kind of entries people might expect to see on the resume of the president of the Manitoba Chambers of Commerce. But then again, Graham Starmer is not your typical business leader.

That’s because the 63-year-old native of Oxford, England, spent the first 27 years of his working life as a police officer and spy catcher, first in his homeland, and then in his adopted country, Canada.

It wasn’t until 1998, after several years working as an investigator for the Manitoba Ombudsman’s Office, that he morphed into a briefcase-toting business leader.

If you’re wondering how that happened, maybe we should start at the beginning, when Starmer graduated from high school and joined the local Thames Valley Police Force.

Within two years, the up-and-comer had been promoted to the regional crime squad, investigating drug offences and other major crimes. It was while there that he helped to bust Jagger for possession of marijuana (see accompanying story).

It was also there that he worked on a case with a liaison officer with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

“He suggested I come to Canada. I thought: ‘More money, bigger country — sounds pretty good!’ “

So in 1969, Starmer packed up his bags and moved to Canada. While waiting to be accepted into the RCMP, he enrolled in a management training program with the Bank of Nova Scotia and was hired as assistant manager of one of its Toronto branches.

But he’d barely settled into that job when he got the call from the RCMP. Next thing he knew, he was on a plane for Regina for six months of rigorous training.

Starmer admits he wasn’t quite prepared for the vast openness of the Canadian Prairies.

“I didn’t understand what the edge of the world was like. I had not perceived there was anything outside of cities.”

After completing his training, he was assigned to the RCMP detachment in Flin Flon for three years. He described it as “an interesting and happy experience,” partly because it was there that he met his future wife, Sylvia, who was a nurse in the local hospital.

The two married in 1972, and a year later they were off to Ottawa after Starmer was assigned to the RCMP Security Service.

For the next 21 years, Starmer worked as a counter-intelligence and counter-terrorism officer first for the RCMP, then the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS).

Because of the sensitive nature of the work, he is reluctant to go into too much detail about those years.

“We were involved in looking at intelligence officers (spies) from other countries and trying to identify them,” he said. “It was extremely interesting and quite productive.”

During that 21-year period, Starmer was twice stationed in Winnipeg. At the end of his second stint here, he quit CSIS and took a job as an investigator with the provincial Ombudsman’s Office instead of moving back to Ottawa.

“My wife’s relatives were in Manitoba, and she didn’t want to move again. And I tended to agree with her.”

It was while working with the Ombudsman’s Office that a headhunter asked him to apply for the newly created full-time position of president of the Manitoba Chambers of Commerce.

Starmer said it wasn’t as big a leap as some might think. During his years with CSIS, he worked on some technology-transfer-related projects involving the local business community and got to know a lot of people and learned about some of the issues.

While it was a big career change, Starmer has no regrets.

“My work with the chambers has been very interesting and challenging, too. Every day is a different day, and every challenge is a new challenge.”

Starmer plans to retire from the Manitoba chambers next May and work part-time on a new project with Winnipeg Harvest executive director David Northcott. They’ll be exploring ways to improve the province’s food bank system.

Winnipeg Chamber of Commerce president Dave Angus, who has worked with Starmer for more than a dozen years, said his replacement will have big shoes to fill.

“One of the aspects of Graham is that he really established himself as a credible voice at the national level,” Angus said, bringing chambers from across the country together to work on projects.

Closer to home, he also has a good working relationship with government officials here, Angus said, and has taken a leadership role on many issues of importance to local businesses.

“And while he’s an imposing figure, he’s really a gentle giant,” Angus added. “He has a very kind heart.”

murray.mcneill@freepress.mb.ca

Manitoba-U.K. trade worth $196M

Manitoba conducted $196-million worth of direct trade last year with the United Kingdom, according to the Manitoba Bureau of Statistics. That included $90.2-million worth of exports to the U.K. and $105.8-million worth of imports* from there.

Here are some of the things we sent them

— $21.9-million worth of wheat

— $16.6-million worth of engines and motors

— $5.6-million worth of parts for helicopters, airplanes, balloons, dirigibles and spacecraft

— $3.3-million worth of dried and shelled legumes

— $1.5-million worth of seeds, fruit and spores for sowing

— $1.2-million worth of automatic data-processing machinery

— $717,000 worth of motor-vehicle parts

— $717,000 worth of turbo-jets, turbo-propellers and other gas turbines

Here are some of the things they sent us

— $11-million worth of pumps for liquids and liquid elevators

— $7.9-million worth of pesticides

— $7.8-million worth of carboxylic acids

— $3.2-million worth of parts for helicopters, airplanes, balloons, dirigibles and spacecraft

— $2.5-million worth of fork-lift trucks and other work trucks fitted with lifting and handling equipment

— $1.9-million worth of turbo-jets, turbo-propellers and other gas turbines

— $1.6-million worth of ceramic tableware, kitchenware and other household articles

— $1.6-million worth of motor-vehicle parts

— $1.6-million worth of self-propelled bulldozers, scrapers, graders, levellers, shovel loaders, and taping machines

— $1.5-million worth of engines and motors

* Goods shipped directly from the U.K. to Manitoba.